Agricultural Change and the Growth of the Creamery System in Monaghan 1855-1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A'railway Or Railways, Tr'araroad Or Trainroads, to Be Called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the Town of Dundalk in the Count

2411 a'railway or railways, tr'araroad or trainroads, to be den and Corrick iti the parish of Kilsherdncy in the* called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the town barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Killnacreena, Cor- of Dundalk in the county .of.Loiith to the town of nacarrew, Drumnaskey, Mullaghboy and Largy in Cavan, in the county of Cavan, and proper works, the parish of Ashfield in the barony of Tullygarvy piers, bridges; tunnels,, stations, wharfs and other aforesaid, Tullawella, Cornabest, Cornacarrew,, conveniences for the passage of coaches, waggons, Drumrane and Drumgallon in the parish of Drung and other, carriages properly adapted thereto, said in the barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Glynchgny railway or railways, tramway or tramways, com- or Carragh, Drumlane, Lisclone, Lisleagh, Lisha- mencing at or near the quay of Dundalk, in the thew, Curfyhone; Raskil and Drumneragh in the parish and town of Dundalk, and terminating at or parish of Laragh and barony of Tullygarvy afore- near the town of Cavan, in the county of Cavan, said, Cloneroy in the parish of Ballyhays in the ba- passing through and into the following townlands, rony of Upper Loughtee, Pottle Drumranghra, parishes, places, T and counties, viz. the town and Shankil, Killagawy, Billis, Strgillagh, Drumcarne,.- townlands of Dundalk, Farrendreg, and Newtoun Killynebba, Armaskerry, Drumalee, Killymooney Balregan, -in the parish of Gastletoun, and barony and Kynypottle in the parishes of Annagilliff and of Upper Dundalk, Lisnawillyin the parish of Dun- Armagh, barony of -

Noeleen Keavev

Noeleen Keavev From: Noeleen Keavey Sent: 13 September 2018 12:21 To: Monaghan County Council (Planning Section) Subject: Mr James Corr, Corlat (Dartree By.), Smithborough, County Monghan - Updated Register Attachments: PO853-02 James Corr-Register.pdf 13/09/2018 Reg. No: PO853-02 Dear Sir/Madam I refer to previous correspondence in relation to the IE application(s) submitted by Mr James Corr, Corlat (Dartree By.), Smithborough, County Monghan It would be appreciated if the attached up-to-date extracts from the Register of Licences could be put on display with the above named file(s) in your public information office. Your co-operation in this matter is greatly appreciated. Should you have any difficulties please do not hesitate to contact this office. Yours faithfully, Environmental Licensing Programme Office of Environmental Sustainability 1 2 Environmental Protection Agency Register of Industrial Emissions Licence Application No. Name and Address of applicant Mr James Corr, Corlat (Dartree By.) Smithborough County Monaghan Class(es) of Activity 6.1 Nature of Activity The rearing of poultry in installations where the capacity exceeds 40,000 places. Location of Activity Corlat (Dartree By.) Smithborough County Monaghan National Grid Reference E2581 N3278 Planning Authority Monaghan County Council Sanitary Authority (if different) Date of Application or review by 24 August 2017 Agency (Regulation 9 compliance see helnwl- _-_ Date of receipt of EIS 24 August 2017 Date of compliance 12 April 2018 I Original. dot Date of receipt of a submission -

National University of Ireland Maynooth the ANCIENT ORDER

National University of Ireland Maynooth THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS IN COUNTY MONAGHAN WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE PARISH OF AGHABOG FROM 1900 TO 1933 by SEAMUS McPHILLIPS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.A. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr. J. Hill July 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgement--------------------------------------------------------------------- iv Abbreviations---------------------------------------------------------------------------- vi Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Chapter I The A.O.H. and the U.I.L. 1900 - 0 7 ------------------------------------43 Chapter II Death and destruction as home rule is denied 1908 - 21-------------81 Chapter III The A.O.H. in County Monaghan after partition 1922- 33 -------120 Conclusion-------------------------------------------------------------------------------143 ii FIGURES Figure 1 Lewis’s Map of 1837 showing Aghabog’s location in relation to County Monaghan------------------------------------------ 12 Figure 2 P. J. Duffy’s map of Aghabog parish showing the 68 townlands--------------------------------------------------13 Figure 3 P. J. Duffy’s map of the civil parishes of Clogher showing Aghabog in relation to the surrounding parishes-----------14 TABLES Table 1 Population and houses of Aghabog 1841 to 1911-------------------- 19 Illustrations------------------------------------------------------------------------------152 -

Filming in Monaghan INTRODUCTION 1

Filming in Monaghan INTRODUCTION 1 A relatively undiscovered scenic location hub. Nestled among rolling drumlin landscape, with unspoilt rural scenery, and dotted with meandering rivers and lakes. Home to some of the most exquisite period homes, and ancient neolithic structures. Discover what Monaghan has to offer... CONTENTS 2 LANDSCAPES 3 BUILDINGS old & new 8 FORESTS and PARKS 15 RURAL TOWNS and VILLAGES 20 RIVERS and LAKES 25 PERIOD HOUSES 29 3 LANDSCAPES LANDSCAPES 4 Lough Muckno Ballybay Wetlands Sliabh Beagh LANDSCAPES 5 LANDSCAPES 6 Concra Wood Golf Club Rossmore Golf Club LANDSCAPES 7 Pontoon, Ballybay Wetlands Rossmore Forest Park 8 BUILDINGS old & new BUILDINGS old & new 9 Drumirren, Inniskeen Lisnadarragh Wedge Tomb Laragh Church Laragh Church Round Tower, Inniskeen BUILDINGS old & new 10 BUILDINGS old & new 11 Signal Box, Glaslough Famine Cottage, Brehon Brewhouse BUILDINGS old & new 12 Ulster Canal Stores Cassandra Hand Centre, Clones Courthouse, Monaghan Magheross Church Carrickmacross Workhouse Dartry Temple BUILDINGS old & new 13 Peace Link Clones Library Garage Theatre Peace Link Atheltic Track Ballybay Wetlands St. Macartans Cathedral, Monaghan BUILDINGS old & new 14 15 FORESTS and PARKS FORESTS and PARKS 16 Lough Muckno Rossmore Forest Park FORESTS and PARKS 17 Dartry Forest Lough Muckno Black Island FORESTS and PARKS 18 Rossmore Forest Park FORESTS and PARKS 19 BUILDINGS old & new 20 PERIOD HOUSES Castle Leslie Estate PERIOD HOUSES 21 Castle Leslie Estate PERIOD HOUSES 22 Hilton Park PERIOD HOUSES 23 Hilton Park PERIOD -

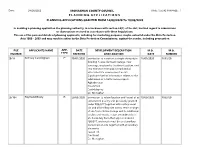

PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED from 14/09/2020 to 18/09/2020

Date: 24/09/2020 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 1:56:42 PM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 14/09/2020 To 18/09/2020 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION M.O. M.O. NUMBER TYPE RECEIVED AND LOCATION DATE NUMBER 20/34 Anthony Cunningham P 30/01/2020 permission to construct a single storey style 16/09/2020 P855/20 dwelling house, domestic garage, new sewerage, wastewater treatment system, and new entrance onto public road and all associated site development works. Significant further information relates to the submission of a traffic survey report Aghadreenan Broomfield Castleblayney Co. Monaghan 20/104 Raymond Brady R 20/03/2020 permission to retain location and layout of as 18/09/2020 P863/20 constructed poultry unit previously granted under P08/627 together with vertical meal bin and all ancillary site works, retain change of use from nitrate storage unit to additional poultry unit on site, retain amendment's to site boundary from that approved under P08/627, and retain meal bin and ancillary store/shed on site together with all ancillary site works Tassan Td. -

Monaghan County Council

DATE : 15/08/2019 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 09:24:25 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 22/07/19 TO 26/07/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 19/337 James Ruxton P 22/07/2019 permission for a development consisting of a four bay agricultural dry bedded shed and all associated site works and retention permission for a development that consists of an agricultural structure. The structure is utilised as a dry-bedded shed for cattle. Shanco Corduff Carrickmacross Co. Monaghan 19/338 Thady Kelly P 22/07/2019 Permission to construct a storey and a half dwelling house, new sewerage wastewater treatment system and new entrance onto public road and all associated site development works Crover (Farney) Broomfield Castleblayney Co Monaghan 19/339 Mr Declan Murray R 22/07/2019 permission for the retention and completion of the front elevational changes to an existing dwelling. These changes include the replacement of the existing brick quoins and detailing on the front porch/projection to a rendered finish to match that of the existing dwelling. -

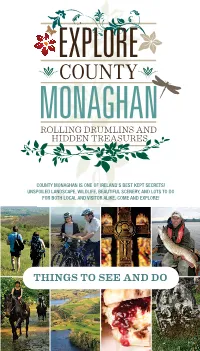

Things to See and Do Our Monaghan Story

COUNTY MONAGHAN IS ONE OF IRELAND'S BEST KEPT SECRETS! UNSPOILED LANDSCAPE, WILDLIFE, BEAUTIFUL SCENERY, AND LOTS TO DO FOR BOTH LOCAL AND VISITOR ALIKE. COME AND EXPLORE! THINGS TO SEE AND DO OUR MONAGHAN STORY OFTEN OVERLOOKED, COUNTY MONAGHAN’S VIBRANT LANDSCAPE - FULL OF GENTLE HILLS, GLISTENING LAKES AND SMALL IDYLLIC MARKET TOWNS - PROVIDES A TRUE GLIMPSE INTO IRISH RURAL LIFE. THE COUNTY IS WELL-KNOWN AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE POET PATRICK KAVANAGH AND THE IMAGES EVOKED BY HIS POEMS AND PROSE RELATE TO RURAL LIFE, RUN AT A SLOW PACE. THROUGHOUT MONAGHAN THERE ARE NO DRAMATIC VISUAL SHIFTS. NO TOWERING PEAKS, RAGGED CLIFFS OR EXPANSIVE LAKES. THIS IS AN AREA OFF THE WELL-BEATEN TOURIST TRAIL. A QUIET COUNTY WITH A SENSE OF AWAITING DISCOVERY… A PALPABLE FEELING OF GENUINE SURPRISE . HOWEVER, THERE’S A SIDE TO MONAGHAN THAT PACKS A LITTLE MORE PUNCH THAN THAT. HERE YOU WILL FIND A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE AND ACTIVITIES TO SUIT MOST INTERESTS WITH GLORIOUS GREENS FOR GOLFING , A HOST OF WATERSPORTS AND OUTDOOR PURSUITS AND A WEALTH OF HERITAGE SITES TO WHET YOUR APPETITE FOR ADVENTURE AND DISCOVERY. START BY TAKING A LOOK AT THIS BOOKLET AND GET EXPLORING! EXPLORE COUNTY MONAGHAN TO NORTH DONEGAL/DERRY AWOL Derrygorry / PAINTBALL Favour Royal BUSY BEE Forest Park CERAMICS STUDIO N2 MULLAN CARRICKROE CASTLE LESLIE ESTATE EMY LOUGH CASTLE LESLIE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE EMY LOUGH EMYVALE LOOPED WALK CLONCAW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE Bragan Scenic Area MULLAGHMORE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GLASLOUGH TO ARMAGH KNOCKATALLON TYDAVNET CASTLE LESLIE TO BELFAST SLIABH BEAGH TOURISM CENTRE Hollywood Park R185 SCOTSTOWN COUNTY MUSEUM TYHOLLAND GARAGE THEATRE LEISURE CENTRE N12 RALLY SCHOOL MARKET HOUSE BALLINODE ARTS CENTRE R186 MONAGHAN VALLEY CLONES PEACE LINK MONAGHAN PITCH & PUTT SPORTS FACILITY MONAGHAN CLONES HERITAGE HERITAGE TRAIL TRAIL R187 5 N2 WILDLIFE ROSSMORE PARK & HERITAGE CLONES ULSTER ROSSMORE GOLF CLUB CANAL STORES AND SMITHBOROUGH CENTRE CARA ST. -

Under 16 Football League

Monaghan Cloghan Annyalla Co. Monaghan 03-04-2014 (Thu) Under 16 Football League Division 3 Gerrys Prepared Veg Ballybay Round 1 Killeevan 18:30 Killeevan V BYE Tyholland 18:30 Tyholland V Castleblayney Scotshouse 18:30 Aghabog V Toome Doohamlet 18:30 Doohamlet V Clones 10-04-2014 (Thu) Under 16 Football League Division 3 Gerrys Prepared Veg Ballybay Round 2 Aghabog 18:30 Aghabog V BYE Toome 18:30 Toome V Doohamlet Clones 18:30 Clones V Tyholland St. Marys Park 18:30 Castleblayney V Killeevan 17-04-2014 (Thu) Under 16 Football League Division 3 Gerrys Prepared Veg Ballybay Round 3 St. Marys Park 18:45 Castleblayney V BYE Tyholland 18:45 Tyholland V Toome Killeevan 18:45 Killeevan V Clones Doohamlet 18:45 Doohamlet V Aghabog 24-04-2014 (Thu) Under 16 Football League Division 3 Gerrys Prepared Veg Ballybay Round 4 Doohamlet 19:00 Doohamlet V BYE Toome 19:00 Toome V Killeevan Scotshouse 19:00 Aghabog V Tyholland St. Marys Park 19:00 Castleblayney V Clones 01-05-2014 (Thu) Under 16 Football League Division 3 Gerrys Prepared Veg Ballybay Round 5 Clones 19:15 Clones V BYE Tyholland 19:15 Tyholland V Doohamlet Killeevan 19:15 Killeevan V Aghabog St. Marys Park 19:15 Castleblayney V Toome 15-05-2014 (Thu) Under 16 Football League Division 3 Gerrys Prepared Veg Ballybay Copyright © 2014 GAA. All rights reserved. No use or reproduction permitted without formal written licence from the copyright holder Page: 1 Round 6 Tyholland 19:30 Tyholland V BYE Scotshouse 19:30 Aghabog V Castleblayney Doohamlet 19:30 Doohamlet V Killeevan Clones 20:00 Clones V Toome 22-05-2014 (Thu) Under 16 Football League Division 3 Gerrys Prepared Veg Ballybay Round 7 Toome 19:30 Toome V BYE Killeevan 19:30 Killeevan V Tyholland Clones 19:30 Clones V Aghabog St. -

Co1. Francis Tummon, Medonagh Barracks, Curragh Camp, Co

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 820 Witness Lieut.-Co1. Francis Tummon, MeDonagh Barracks, Curragh Camp, Co. Kildare. Identity. Member of Irish Volunteers, - Co. Monaghan, 1918 Subject. National activities, Cos. Monaghan arid Cavan, 1916-1922. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2130 Form B.S.M.2 Lieut. - Colonel F. Tummon, McDonagh Barracks, Curragh Camp, Co. Kildare. Recollections of a Volunteer in Irish Republican Army 1916-1921 Chapter 1. 1916: This is a story of what happened in a period of my life. It is written about 30 years after the period 1916-1921, or in the year 1952 to be exact. I clearly recollect one Sunday morning in April, 1916, having walked a distance of three miles from my home to attend last Mass in the town of Newtownbutler, Co. Fermanagh, an announcement was read by the Parish Priest during Mass to the effect that an instrument of unconditional surrender had been signed on behalf of the Irish Volunteers by P. H. Pearse. This announcement stuck in my memory. It evidently had been prepared by the local Sergeant of the Royal Irish Constabulary on behalf of His Majesty's Government and handed for publication to the Catholic clergyman. While I've no doubt the majority of the congregation on that Sunday morning were aware a rebellion against British rule had the been in progress during previous week, few indeed knew who this man Pearse was or what he stood for. The older men shook their heads and expressed the opinion that the use of arms was a misguided action and doomed to failure from the start. -

Inspector's Report PL18.248569

Inspector’s Report PL18.248569 Development Five bay double slatted shed, silage pit with concrete apron, effluent connection to propose slatted pit. Location Golanmurphy, Dartree, Smithborough, County Monaghan. Planning Authority Monaghan County Council Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 17/03 Applicant(s) Adam Hall Type of Application Permission Planning Authority Decision Refuse Type of Appeal First Party Appellant(s) Adam Hall Observer(s) None 9th August 2017 Date of Site Inspection Inspector Hugh Mannion PL18.248569 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 11 Contents 1.0 Site Location and Description .............................................................................. 3 2.0 Proposed Development ....................................................................................... 3 3.0 Planning Authority Decision ................................................................................. 3 3.1. Decision ........................................................................................................ 3 3.2. Planning Authority Reports ........................................................................... 3 3.3. Prescribed Bodies ......................................................................................... 4 3.4. Third Party Observations .............................................................................. 4 4.0 Planning History ................................................................................................... 5 5.0 Policy Context ..................................................................................................... -

Monaghan County Development Plan 2019 - 2025

MONAGHAN COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2019 - 2025 Comhairle Contae Mhuineacháin March 2019 Monaghan County Development Plan 2019-2025 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction Section Section Name Page No. 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Plan Area 1 1.2 Plan Title 2 1.3 Legal Status 3 1.4 Challenges for County Monaghan 5 1.5 Content and Format 6 1.6 Preparation of the Draft Plan 6 1.7 Pre-Draft Consultation 6 1.8 Stakeholder Consultation 7 1.9 Chief Executive’s Report 7 1.10 Strategic Aim 7 1.11 Strategic Objectives 7 1.12 Policy Context 8 1.13 Strategic Environmental Assessment 15 1.14 Appropriate Assessment 16 1.15 County Profile 16 1.16 Population & Demography 17 1.17 County Monaghan Population Change 17 1.18 Cross Border Context 20 1.19 Economic Context 21 Chapter 2 Core Strategy Section Section Name Page No. 2.0 Introduction 23 2.1 Projected Population Growth 24 2.2 Economic Strategy 26 2.3 Settlement Hierarchy 27 2.3.1 Tier 1-Principal Town 27 2.3.2 Monaghan 28 2.3.3 Tier 2- Strategic Towns 29 2.3.4 Carrickmacross 30 2.3.5 Castleblayney 30 2.3.6 Tier 3 -Service Towns 30 2.3.7 Clones 31 2.3.8 Ballybay 31 i Monaghan County Development Plan 2019-2025 2.3.9 Tier 4 -Village Network 31 2.3.10 Tier 5 -Rural Community Settlements 32 2.3.11 Tier 6- Dispersed Rural Communities 32 2.4 Population Projections 33 2.4.1 Regeneration of Existing Lands 33 2.4.2 Housing Need Demand Assessment 2019-2039 35 2.5 Core Strategy Policy 37 2.6 Rural Settlement Strategy 39 2.7 Housing in Rural Settlements 41 2.7.1 Rural Settlement objectives and policies 42 2.8 Rural Area Types 44 2.8.1 Category 1 – Rural Areas Under Strong Urban Influence 45 2.8.2 Category 2 – Remaining Rural Area 47 2.9 Unfinished Housing in Rural Areas Under Strong Urban 47 Influence Chapter 3 Housing Section Section Name Page No. -

Submission Acknowledge on Pig & Poultry Applications

From: Licensing Staff Sent: 20 July 2018 11:34 Subject: Submission Acknowledge on Pig & Poultry applications/reviews Dear Mr Sweetman I acknowledge receipt of your email on 17th July 2018 in relation to a number of licence applications/reviews set out in the table below. DDS BRADY FARMS Carrickboy Farms, Ballyglasson, P0408-02 LIMITED Edgeworthstown, County Longford. P0422-03 Silver Hill Foods Hillcrest, Emyvale, County Monaghan. P0515-02 Laragan Farms Limited Laragan, Elphin, County Roscommon. P0640-02 Mr John Kiernan Tullynaskeagh, Bailieboro, County Cavan. P0790-03 Mr EoinOBrien Annistown, Killleagh, County Cork. P0837-03 F. OHarte Poultry Limited Creevaghy, Clones, County Monaghan. Corlat (Dartree By.), Smithborough, County P0853-02 Mr James Corr Monaghan. P0861-03 Mr Bernard Treanor Doogary, Tydavnet, County Monaghan. P0871-02 Mr Vincent Quinn Cornanagh, Ballybay, County Monaghan. P0878-03 Glenbeg Poultry Limited Glenbeg, Carrickroe, County Monaghan. P0879-02 Mr Leo Treanor Corvoy, Ballybay, County Monaghan. P0880-02 Mr Brian Coleman Longfield, Castleblayney, County Monaghan. P0926-03 Mr Nigel Flynn Tiernahinch Far, Clones, County Monaghan. Tankerstown Pig & Farm Tankerstown, Bansha, Tipperary, County P0965-01 Enterprises Limited Tipperary. Joristown Upper, Killucan, County Westmeath, P0975-02 Clondrisse Pig Farm Limited N91 HK27. P0976-03 Senark Farm Limited Aghnaglough, Stranooden, County Monaghan. P0979-01 Thomas & Trevor Galvin Ballyharrahan, Ring, Co Waterford. P1024-02 Doon Farm Enterprises Limited Doon, Araglin, Kilworth, County Tipperary. Messrs Gerard & Raymond P1029-02 Davagh Otra, Emyvale, County Monaghan. Tierney P1031-02 Kilfilum Limited Nantinan, Milltown, County Kerry. P1032-02 Mile Tree Farms Limited Clashiniska Lower, Clonmel, County Tipperary. P1041-01 Stephen and Carol Brady Clontybunnia, Scotstown, County Monaghan.