R.I. Page, on the Transliteration of English Runes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

Elder Futhark Runes (1/2) (9 Points)

Ozclo2015 Round 1 1/15 <1> Elder Futhark Runes (1/2) (9 points) Old Norse was the language of the Vikings, the language spoken in Scandinavia and in the Scandinavian settlements found throughout the Northern Hemisphere from the 700’s through the 1300’s. Much as Latin was the forerunner of the Romance languages, among them Italian, Spanish, and French, Old Norse was the ancestor of the North Germanic languages: Icelandic, Faroese, Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish. Old Norse was written first in runic alphabets, then later in the Roman alphabet. The first runic alphabet, found on inscriptions dating from throughout the first millennium CE, is known as “Elder Futhark” and was used for both proto- Norse and early Old Norse. Below are nine Anglicized names of Old Norse gods and the nine Elder Futhark names to which they correspond. Listed below are also two other runic names for gods. The names given below are either based on the gods’ original Old Norse names, or on their roles in nature; for instance, the god of the dawn might be listed either as ‘Dawn’ or as Delling (his original name). Remember that the modern version of the name may not be quite the same as the original Old Norse name – think what happened to their names in our days of the week! Anglicized names: Old Norse Runes: 1 Baldur A 2 Dallinger B 3 Day C 4 Earth 5 Freya D 6 Freyr E 7 Ithun F 8 Night G 9 Sun H I J K Task 1: Match the runes to the correct names, by placing the appropriate letter (from A to K) for the runic word corresponding in meaning to the anglicized name in the first table. -

Boofi 6HEEH SIATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY I

RUNIC EVIDENCE OF LAMINOALVEOLAR AFFRICATION IN OLD ENGLISH Tae-yong Pak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1969 Approved by Doctoral Committee BOOfi 6HEEH SIATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY I 428620 Copyright hy Tae-yong Pak 1969 ii ABSTRACT Considered 'inconsistent' by leading runologists of this century, the new Old English runes in the palatovelar series, namely, gar, calc, and gar-modified (various modi fications of the old gifu and cën) have not been subjected to rigorous linguistic analysis, and their relevance to Old English phonology and the study of Old English poetry has remained unexplored. The present study seeks to determine the phonemic status of the new runes and elucidate their implications to alliteration. To this end the following methods were used: 1) The 60-odd extant Old English runic texts were examined. Only four monuments (Bewcastle, Ruthwell, Thornhill, and Urswick) were found to use the new runes definitely. 2) In the four texts the words containing the new and old palatovelar runes were isolated and tabulated according to their environments. The pattern of distribution was significant: gifu occurred thirteen times in front environments and twice in back environments; cen, eight times front and once back; gar, nine times back; calc, five times back and once front; and gar-modified, twice front. Although cen and gifu occurred predominantly in front environments, and calc and gar in back environments, their occurrences were not complementary. 3) To interpret the data minimal or near minimal pairs with the palatovelar consonants occurring in front or back environments were examined. -

ALPHABET and PRONUNCIATION Old English (OE) Scribes Used Two

OLD ENGLISH (OE) ALPHABET AND PRONUNCIATION Old English (OE) scribes used two kinds of letters: the runes and the letters of the Latin alphabet. The bulk of the OE material — OE manuscripts — is written in the Latin script. The use of Latin letters in English differed in some points from their use in Latin, for the scribes made certain modifications and additions in order to indicate OE sounds which did not exist in Latin. Depending of the size and shape of the letters modern philologists distinguish between several scripts which superseded one another during the Middle Ages. Throughout the Roman period and in the Early Middle Ages capitals (scriptura catipalis) and uncial (scriptura uncialis) letters were used; in the 5th—7th c. the uncial became smaller and the cursive script began to replace it in everyday life, while in book-making a still smaller script, minuscule (scriptura minusculis), was employed. The variety used in Britain is known as the Irish, or insular minuscule. Insular minuscule script differed from the continental minuscule in the shape of some letters, namely d, f, g. From these letters only one is used in modern publications of OE texts as a distinctive feature of the OE alphabet – the letter Z (corresponding to the continental g). In the OE variety of the Latin alphabet i and j were not distinguished; nor were u and v; the letters k, q, x and w were not used until many years later. A new letter was devised by putting a stroke through d or ð, to indicate the voiceless and the voiced interdental [θ] and [ð]. -

Viking-Age Runic Plates of the Runic Plates Have Been Conducted with a Stereomicroscope for This Purpose

The aim of this dissertation is to represent as clearly as possible the genre of Viking- Age runic plates by developing readings and interpretations of the inscriptions on the 46 metal plates with runes from the Viking Age known today. Several investigations SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH • • PERESWETOFF-MORATH SOFIA Viking-Age Runic Plates of the runic plates have been conducted with a stereomicroscope for this purpose. On the basis of the new readings thus established, new interpretations have been pro- posed for the most problematic sections of previously interpreted inscriptions. New interpretations are also offered for inscriptions on runic plates which have previously been considered non-lexical. As well as providing new readings and interpretations, this study has resulted in clarification of the relationship between the form and content of the inscriptions on the runic plates on the one hand and on their find circumstances and appearance on the other. An argued documentation of the readings can be found in an accompanying catalogue in Swedish which is published digitally and can be downloaded as a pdf file at: <http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-383584> Viking-Age Runic Plates Viking-Age Distribution: Sofia Pereswetoff-Morath eddy.se ab e-post: [email protected] ISSN 0065-0897 and Box 1310, 621 24 Visby. Telefon: 0498-25 39 00 ISSN 1100-1690 http://kgaa.bokorder.se ISBN 978-91-87403-33-0 1 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI 155 Runrön 21 Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 2 3 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI CLV Runrön 21 Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH Viking-Age Runic Plates Readings and Interpretations Translated from Swedish by Mindy MacLeod UPPSALA 2019 Kungl. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

New Bracteate Finds from Early Anglo-Saxon England by CHARLOTTE BEHR1

Medieval Archaeology, 54, 2010 New Bracteate Finds from Early Anglo-Saxon England By CHARLOTTE BEHR1 THE NUMBER OF bracteate finds from early Anglo-Saxon England has increased substan- tially in recent years. A catalogue draws together for the first time all the finds since 1993 and one, possibly two, dies with bracteate motifs. This leads to a review of their find circum- stances, distribution and their stylistic and iconographical links with continental and Scandi- navian bracteates. The outcome is a revised picture of the function and meaning of bracteates in Anglo-Saxon society, with the suggestion that the English adopted the idea for these pendants from Sievern in Germany but adapted the concept and iconography for local manufacture. In Kent use links to high-status female burials but outside Kent ritual deposition is also a possibility. With over 980 objects, mostly from Scandinavia, bracteates form one of the largest find groups in 5th- and 6th-century northern European archaeology. Examples from the early Anglo-Saxon period are yet another find group that has in recent years increased considerably thanks to metal-detector finds and their systematic recording in the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and the Treasure Annual Reports (TAR). Archaeological excavations have also contri- buted several new finds.2 Bracteates are round pendants usually made out of gold foil, occasionally silver or bronze foil, with a stamped central image. Dated to the second half of the 5th and first half of the 6th centuries, they were looped and worn on necklaces. The central image was figurative showing either one or more animals or an anthropomorphic head or figure often together with animals.3 Depending on the size of the metal sheet, one or more concentric rings, sometimes decorated with individual geometrical stamps, surround the image. -

Ancient and Other Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

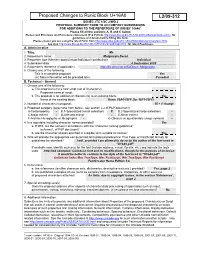

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4. -

THE NINE DOORS of MIDGARD a Curriculum of Rune-Work

,. , - " , , • • • • THE NINE DOORS OF MmGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work - • '. Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin·Drighten of the Rune-Gild THE NINE DOORS OF MIDGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin-Drighten of the Rune-Gild 1997 - Introduction This work is the first systematic introduction to Runelore available in many centuries. This age requires and allows some new approaches to be sure. We have changed over the centuries in question. But at the same time we are as traditional as possible. The Gild does not fear innovation - in fact we embrace it - but only after the tradition has been thoroughly examined for all it has to offer. Too often in the history of the runic revival various proponents have actually taken their preconceived notions about what the Runes should say- and then "runicized" them. We avoid this type of pseudo-innovation at all costs. Our over-all magical method is a simple one. The tradition posits an outer world (objective reality) and an inner-world (subjective reality). The work of the Runer is the exploration of both of these worlds for what they have to offer in the search for wisdom. In learning the Runes, the Runer synthesizes all the objective lore and tradition he can find on the Runes with his subjective experience. In this way he "makes the Runes his own." All the Runes and their overall system are then used as a sort of "meta-Ianguage" in meaningful communication between these objective and subjective realities. The Runer may wish to be active in this communication - to cause changes to occur in accordance with his will, or he may wish to learn from one of these realities some information which would normally be hidden from him. -

Runes and Verse: the Medialities of Early Scandinavian Poetry

Runes and Verse: The Medialities of Early Scandinavian Poetry Judith Jesch Introduction: Runic and Roman in Old English and Old Norse Poetry It has long been recognised that there are many similarities between Old English and Old Norse literary culture and especially poetry, despite their chronological disparities. While many scholars nowadays prefer to stress these chronological and other disparities, or simply to ignore the similarities and concentrate on just the one tradition, there is still room for a nuanced comparison of the two bodies of poetry, as in for example recent work by Matthew Townend. Having examined some similarities in poetic diction he argues that these derive in part from the common roots of Old English and Old Norse. Such a shared specialised poetic diction suggests to him “that there existed a well-developed North-West Germanic poetic culture ... the reflexes of which can be observed in our extant Old English and Old Norse verse” (Townend 2015, 18). As well as this similarity of poetic vocabulary, and of course their well-known common metrical structures, these two corpora also share certain structural similarities which relate not only to patterns of transmission but also to the wider role of verse in their respective cultures. Thus, it is worthy of note that both corpora include anonymous as well as non-anonymous verse, and both include verse that is transmitted in runic inscriptions as well as in manuscripts in the roman alphabet. But despite these similarities, the poetical cultures of Anglo-Saxon England and early Scandinavia display significant differences, in particular when these medialities of roman and runic are considered more closely. -

Runatal 1Up (PDF)

RÚNATAL Fjár Ætt (Family or lineage of Fé or Wealth) Rune Phoneme Meaning Rune Name Description Cattle which have been domesticated, and represent portable wealth (as opposed to FEE FEHU – fé f! f real estate, which is not portable), money or wealth, increase from wise investment Aurochs, which was the long-horned undomesticated bovine prevalent in AUROCHS ÚRUZ Europe, North Africa and Asia Minor, U! u measuring 6 foot at the shoulder. Thus, the wilder, untamed forces. Jötunn (pl. jœtnar), a Chthonic spirit force lacking the necessary structuring which would lead to acts of creation or THURS ÞURISAZ – þurs Q th nurture. Coincidentally, it is also the first rune in the name Þórr, who was called upon to hallow the runes. One of the ÆsiR, originally spirits/gods of a! a Ase ANSUZ – áss the air and meteorological phenomena. Carriage, wagon or other conveyance for RIDE RAIÐÔ – reið transporting goods or people. Also ráðr R! r meaning advice, teaching. KEN, meaning torch or flame and illness. Thus, perhaps a purifying fever, or the torch KAUNAN – ken purificatory flames of transformation. The k! k bone-fire blazing on the hill-top lures us into its mystery. A gift or present. Partnerships, both in g! g GIFT GEBÔ – gefu love and in business. Old English wynn = laughter. Joy, W! w joy WÛNJÔ – wynn celebration, fröjd. 1 HAGLA ÆTT (Family or lineage of HagalaZ or Hail) Rune Phoneme Meaning Rune Name Description Hail, a disruptive natural force which is h h HAIL HAGALAZ difficult to prepare for. Need, emergency, hunger, hunting in NAUÐIZ NEED winter, a sinking ship.