Te Rohe Potae Maori: Twenty-First Century Socio-Demographic Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Errata and Updated Statistics for the 2014 Annual Climate Summary Issued

Errata and updated statistics for the 2014 Annual Climate Summary Issued: 16 April 2015 Every year, an annual climate summary and a table of annual statistics are provided by NIWA, usually within the first two weeks of January. This summary is based on data available at the time, and often includes preliminary (real-time) annual climate statistics which are as yet not fully quality checked. Each year during April, the annual statistics from the calendar year prior are updated, including both automated and manual climate station data. The purpose of the update is two-fold; to enable manual climate data to be incorporated, since manual stations typically take 1-2 months for data to be received and entered into the National Climate Database; and to log errata found in subsequent quality checks performed in the National Climate Database, or site visits undertaken in January and February. This update is for the 2014 annual climate summary. This update was based on available data as at 1 April 2015. Errata and notes 1. Following the update of station data contained within the Water Resources Archive, the rankings for wettest sites in New Zealand for 2014 have changed. The wettest four locations are now: Cropp River at Waterfall (11866 mm), Tuke River at Tuke Hut (10728 mm), Cropp River at Cropp Hut (10655 mm), and Haast River at Cron Creek (8239 mm). 2. Offshore and outlying island stations were not included in this update. 3. Some sites have missing days of data. The number of missing days is indicated by a superscript number next to the annual value in the tables below. -

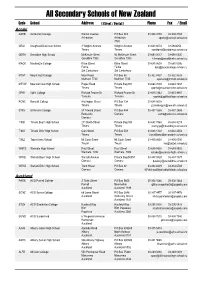

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Agenda of Environment Committee

I hereby give notice that an ordinary meeting of the Environment Committee will be held on: Date: Wednesday, 29 June 2016 Time: 9.00am Venue: Tararua Room Horizons Regional Council 11-15 Victoria Avenue, Palmerston North ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE AGENDA MEMBERSHIP Chair Cr CI Sheldon Deputy Chair Cr GM McKellar Councillors Cr JJ Barrow Cr EB Gordon (ex officio) Cr MC Guy Cr RJ Keedwell Cr PJ Kelly JP DR Pearce BE Rollinson Michael McCartney Chief Executive Contact Telephone: 0508 800 800 Email: [email protected] Postal Address: Private Bag 11025, Palmerston North 4442 Full Agendas are available on Horizons Regional Council website www.horizons.govt.nz Note: The reports contained within this agenda are for consideration and should not be construed as Council policy unless and until adopted. Items in the agenda may be subject to amendment or withdrawal at the meeting. for further information regarding this agenda, please contact: Julie Kennedy, 06 9522 800 CONTACTS 24 hr Freephone : [email protected] www.horizons.govt.nz 0508 800 800 SERVICE Kairanga Marton Taumarunui Woodville CENTRES Cnr Rongotea & Hammond Street 34 Maata Street Cnr Vogel (SH2) & Tay Kairanga-Bunnythorpe Rds, Sts Palmerston North REGIONAL Palmerston North Wanganui HOUSES 11-15 Victoria Avenue 181 Guyton Street DEPOTS Levin Taihape 11 Bruce Road Torere Road Ohotu POSTAL Horizons Regional Council, Private Bag 11025, Manawatu Mail Centre, Palmerston North 4442 ADDRESS FAX 06 9522 929 Environment Committee 29 June 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Apologies and Leave of Absence 5 2 Public Speaking Rights 5 3 Supplementary Items 5 4 Members’ Conflict of Interest 5 5 Confirmation of Minutes Environment Committee meeting, 11 May 2016 7 6 Environmental Education Report No: 16-130 15 7 Regulatory Management and Rural Advice Activity Report - May to June 2016 Report No: 16-131 21 Annex A - Current Consent Status for WWTP's in the Region. -

Te Awamutu Courier Thursday, May 27, 2021

Rural sales specialist Noldy Rust 027 255 3047 | rwteawamutu.co.nz Thursday, May 27, 2021 Rosetown Realty Ltd Licensed REAA2008 BRIEFLY Centre gets behind Ohaupo Rd crash Police confirmed that a truck driver died yesterday after the truck and a car collided on Ohaupo Road just before 1pm. The crash occured between cystic fibrosis month Te Rahu Rd and Greenhill Dr and a number of traffic diversions were in place. Large plumes of black smoke could be seen billowing from the Blue bubble day scene. Fire, police and St John were at the scene. supports preschooler House name hui The deadline for submissions Caitlan Johnston for the change of the four Te Awamutu College house childcare centre has really names has been extended to showed their support for Friday, June 11. A hui is being one of their pupils who has held at O-Ta¯whao Marae on cystic fibrosis. Thursday, June 3 at 7.30pm to AImpressions Childcare Centre in provide an opportunity for Pirongia has only just welcomed people to talk and freely Noah Crawford who is 3 years old discuss the proposal. now but at just 6 weeks old was Everyone is welcome. diagnosed with the disorder that affects the lungs and digestive sys- tem. Challenges for 2021 Noah is the only and first child at Returning to Te Awamutu the childcare centre to attend who Continuing Education next has the disorder. Wednesday, by popular “We felt really lucky that here is demand, is Professor Al the first place he’s been without his Gillespie. His topic will be mum but none of us knew anything Challenges for NZ in 2021. -

Te Awamutu Courier Thursday, May 20, 2021 from Prison to Young Ma¯Ori Farmer Award

Ph (07) 871-5069 email: [email protected] 410 Bond Road, Te Awamutu Thursday, May 20, 2021 A/H 021 503 404 BRIEFLY Dairy award finalist Clothing Swap returnsinJune The Clothing Swap will take place in theTeAwamutu Baptist Church Hall on now helping others Thursday,June 3from 7-9pm and everyone is welcome. If you have items to donate, drop them to the church office at 106 Teasdale St Monday – Thursday between 9am and From prison to 2pm.For more information phone 022 101 2153. Young Ma¯ori Te Rahu Table Farmer Awards Tennis Club Te Rahu Table Tennis Club are Dean Taylor looking for new members to join their club nights. ast Friday night Ben Purua The club meet at Te RahuHall stood on the stage at the on corner of Te RahuRdand Ahuwhenua Trophy Dairy O¯ haupo¯ Rd (between Te L Competition Awards Dinner Awamutu and O¯ haupo¯). as one of three finalists in the Young Monday nights at 7.30pm from Ma¯ori Farmer Award. April-November. New Ten years ago, as ateenager, he members are always stood being judged in avery different welcome. environment; the dock of Hamilton Checkout their Facebook High Court being sentenced after page for more details -Te pleading guilty to manslaughter. RahuTable Tennis Club -Te Two accomplices also pleaded Awamutu area. guilty to murder and manslaughter and all were sent to prison. Ben was sentenced to five-and- Paint Waipa¯Pink a-half years, and served four years at Today is the last day for Waikeria Prison. customers to vote for their Last week he was back inside, but favourite ‘pink’ shop windows this time accompanied by his wife before tomorrows prizegiving. -

Meringa Station Forest

MERINGA STATION FOREST Owned by Landcorp Farming Ltd Forest Management Plan For the period 2016 / 2021 Prepared by Kit Richards P O Box 1127 | Rotorua 3040 | New Zealand Tel: 07 921 1010 | Fax: 07 921 1020 [email protected] | www.pfolsen.com FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN MERINGA STATION FOREST Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................2 2. Forest Investment Objectives ......................................................................................................3 OPERATING ENVIRONMENT .....................................................................................................................5 3. Forest Landscape Description .....................................................................................................5 Map 1: Meringa Station Forest Location Map .........................................................................................7 4. The Ecological Landscape ............................................................................................................8 Map 2: Forest by Threatened Environments Classification .................................................................. 10 5. Socio-economic Profile and Adjacent Land .............................................................................. 11 6. The Regulatory Environment .................................................................................................... 13 FOREST MANAGEMENT ........................................................................................................................ -

(150 ) Anniversary Commemoration of the Battle of O-Rãkau

Preparing For The Sesquicentennial (150th) Anniversary Commemoration Of The Battle Of O-Rãkau (March 31st - April 2nd 1864) HOSTED BY THE BATTLE OF O-RÃKAU HERITAGE SOCIETY INC O-Rãkau Battlefield, Arapuni Road, Kihikhi Tuesday 1st & Wednesday 2nd April 2014 Kupu Whakataki Introduction He reo pōwhiri e karanga ana i te takiwā Nau mai,piki mai,haere mai. Haere mai. e ngā iwi e ngā reo e ngā waka. Whakatata mai ki te papa i mura ai i te ahi, i pakū ai ngā pū, i hinga ai ngā tupuna. E whakatau ana i a koutou ki runga i te papa o te Parekura o O-Rãkau. Nau mai haere mai. April 1st 2014 is the day we have set aside to come together to remember, to honour and to give substance to the legacy left behind by those who fought and fell at O-Rãkau from March 31st to April 2nd 1864. That battle which saw so much carnage and death, which became a turning point in the history of the Waikato and Auckland provinces and indeed the entire Nation. After 150 years, it is now time for us to take a breath, and to meditate on how far we have come and how much further there is yet to go before we can with honesty say, we are honouring the sacred legacy left in trust to this country by so many whose lives were sacrificed upon the alter of our nationhood. Those who fell at O-Rãkau, Rangiaowhia, Hairini, Waiari, Rangiriri in the Waikato war, lest we forget also the War in the North, the East Cape, Waitara, Whanganui, South and Central Taranaki, Hutt valley and Wairau in the South Island. -

Demographics Profile Statement

Ê¿´«» ±«®  ó ݸ¿³°·±² ±«® Ú«¬«®» ÜÛÓÑÙÎßÐØ×ÝÍ ÐÎÑÚ×ÔÛ ÍÌßÌÛÓÛÒÌ Table of Contents 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Purpose..................................................................................................................................1 1.3 Definitions..............................................................................................................................1 1.4 Assumptions and Limitations...................................................................................................2 1.5 Source Material......................................................................................................................2 1.6 Report Structure.....................................................................................................................2 2 Demographic Snapshot 2006..........................................................................................4 2.1 Geographic Units....................................................................................................................4 2.2 District Profile.........................................................................................................................4 2.3 Urban Profile..........................................................................................................................6 -

Te Awamutu Community Board 9 March 2020 - Agenda

Te Awamutu Community Board 9 March 2020 - Agenda Te Awamutu Community Board 9 March 2020 Council Chambers, Waipa District Council, 101 Bank Street, Te Awamutu AM Holt (Chairperson), CG Derbyshire, RM Hurrell, J Taylor, KG Titchener, Councillor LE Brown, Councillor SC O'Regan 09 March 2021 06:00 PM Agenda Topic Page 1. Apologies 3 2. Disclosure of Members' Interests 4 3. Late Items 5 4. Confirmation of Order of Meeting 6 5. Public Forum 7 6. Confirmation of Minutes 8 6.1 Te Awamutu Community Board Minutes 9 February 2021 9 7. Draft Memorial Park Concept Plan - Public feedback and staff recommendations 14 8. Quarterly Reports 42 8.1 Community Services Quarterly Report 43 8.2 Property Quarterly Report 63 8.3 Transportation Quarterly Report 74 9. Community Board Rural Tour 2021 87 9.1 Appendix 1 - Te Awamutu & Kakepuku Wards Map 90 10. Treasury Report 91 11. Discretionary Fund Application 94 11.1 Appendix 1 - Discretionary Fund Application 95 12. Chairperson's Report 98 1 Te Awamutu Community Board 9 March 2020 - Agenda 13. Board Members Report from Meetings attended on behalf of the Te Awamutu Community 100 Board 14. Date of Next Meeting 101 2 Te Awamutu Community Board 9 March 2020 - Apologies To: The Chairperson and Members of the Te Awamutu Community Board From: Governance Subject: Apologies A member who does not have leave of absence may tender an apology should they be absent from all or part of a meeting. The Chairperson (or acting chair) must invite apologies at the beginning of each meeting, including apologies for lateness and early departure. -

TE TIRO HAN GA I TE KOREROT ANGA 0 TE REO RANGATIRA I ROTO I NGA KAINGA MAORI ME NGA ROHE Survey of Language Use in Maori Households and Communities

TE TIRO HAN GA I TE KOREROT ANGA 0 TE REO RANGATIRA I ROTO I NGA KAINGA MAORI ME NGA ROHE Survey of Language Use in Maori Households and Communities PANUI WHAKAMOHIO INFORMATION BULLETIN 101 ISSN 0113-3063 Localities in which ten or more households were visited e Two thirds or more of adults were fluent speakers of Maori + Less than two thirds of adults were fluent speakers of Maori HEPURONGORONGO + WHAKAMOHIO MA NGA KAIURU KI TE TORONGA TUATAHI, 1973-1978 A report to Participants in the Initial Investigation, 1973-1978 Te Awamutu A. • "v • • Tokoroae Map showing Towns and Localities in the Taupo-Taumarunui District • Visited during the Census of "v Language Use. The Maori Language in Te Awamutu and District Fieldwork for the survey of language use in Maori communities was carried out in Te Awamutu, Kihikihi, Owairaka and Parawera in February , May and August of 1976, and May 1977 . The interviewers were Phillip Hawera CTuhoe/Ngai • Taumarunui e A. e te Rangi/Ngati Awa), Judith Brown Hawera ( Waikato), "v Joe Rua (Te Whanau-a-Apanui), Ameria Ponika CTuhoe), Turangi"v Maku Potae CNgati Porou), Kathleen Grace Patee • CTuwharetoa) and Raiha Smith CNgati Kahungunu). Ten households with a total population of ~9 were visited in Te Awamutu's total Maori population at that time. 16 households in the surrounding district were also included in the survey. These had a combined population of 79, 77 of whom were of Maori descent (about 16 percent of the area's total Maori population at that time). Two interviews were carried out -entirely in Maori, one in both Maori and English and the Percentage of fluent speakers of Maori @ More than 60% A. -

The New Zealand Gazette. 2465

OCT. 2.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 2465 266409 Herbert, Ronald Ernest, Garage Attendant, Pukekapia 295292 Hudner, Patrick Francis, Barman, Empire Privat.e Hotel, Rd, Ruawaro Rd, Huntly. Frankton Junction. 109804 Herlihy, John Charles, Winch-driver, Kihikihi, Te 409091 Huggins, Albert Alexander, Farmer, Tuhikaramea Rd, Awamutu. Frankton. 179423 Hewett, Basil Stuchburgh, Farmer, Roto-o-rangi, Cambridge. 404932 Hughes, Colin, Farm Labourer, Ruawaro, Huntly. 275363 Hey, Ernest Hodgson, Clerk, 7 Keddell St, Frankton 406562 Hughes, Edward Robert David, Farm Labourer, Mangao Junction. ronga Rd, Otorohanga. 272850 Hickey, Ronald George, Farm Hand, Anzac St, Cambridge. 144008 Humphrey, John Francis, Storeman, 11 Lake Avenue, 245239 Hicks, Edmund Penhellick, Farm Labourer, Horahora, Frankton. · Cambridge. 178088 Humphrey, John Meldrum, Farm Labourer, Ohura. 265574 Hickson, John Theodore, Clerk in Holy Orders, Awakino. 418591 Humphrey, William Henry, Dairy-farmer, Piako Rd, 402384 Higgins, Norman Liston, Moore St, Leamington, Cambridge. Gordonton, Waikato. 076061 Higgins, Peter Joseph, care of Mr. H. N. Fullerton, Te Rapa. 146274 Hunt, Cyril Godfrey, Watchmaker, 22 Pembroke St, 409948 Higgins, Stanley Clifford, Railway Porter, care of Railways, Hamilton. Te Kuiti. 273478 Hunt, Francis Dennis, Porter, care of New Zealand Railways, 317878 Higgins, William Arthur, Builder's Labourer, Raits Block, Taumarunui. Te Kuiti. 426677 Hunter, George Gillies (Jun.), Coal-miner, Rotowaro. 404768 Higginson, Alfred Hopkins, Farm Hand, Rural Delivery, 404661 Hunter, Matthew, Miner, Hakanoa St, Huntly. Piopio. 232605 Hurrell, Roy Thomas George, Panel-beater, care of Mrs. 196052 Higginson, Deryck, Wynleigh, Clerk, 13 St. Olphert's Hyslop, 24 Firth St, Hamilton East. Avenue, Claudelands, Hamilton. 425989 Hutchins, Douglas Roy, Baker, Taupiri St, Te Kuiti. 227131 Higginson, Leslie Wilfred, Shop-assistant, 13 St. -

The New Zealand Gazette 3123

:10 NOVEMBER THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 3123 Hangatiki, Public School. Papakura- Hawera, Memorial Theatre. Artillery Drive Play Centre. Homai, corner Browns and Russell Road, Homai Service Beach Road, Public School. Station. Coles Crescent, Anglican Church Hall. Horotiu, Public School. Cosgrove Road, Public School. Hunterville, Consolidated School. Great South Road, Old Central School. Huntly- Jupiter Street, Rosehill Intermediate School. Waahi Pa, Marae. Kelvin Road, Public School. Huntly War Memorial Hall._ Porchester Road, Normal School. Inglewood, Town Hall. Red Hill, Public School. Kaiaua, Public School. Willis Road, Papakura High School. Kakahi, Public School. Papatoetoe-- Kakaramea, Public School. Puhinui Road, School. Kauangaroa, Public School. St. Johns Presbyterian Church Hall, Hunters Comer. Kawhia, Community Hall. Town Hall, St George Street. Kerepehi, Public School. Parawera, Public School. Kihikihi, Town Hall. Patea- · Kinohaku, Public School. High School. Kurutau, Public School. Primary School. Mania, Public School. Piopio, Primary School. Mangakino, Social Hall. Pirongia, Public School. Mangaweka, Public School. Pokeno, Public School. Mangere Bridge, Coronation Road, Mangere Bridge School. Port Waikato, Yacht and Motor boat clubrooms. Mangere Central- Pukekohe-- Kirkbride Road, Mangere Central School. Hill School. McNaughton Avenue, Southern Cross School. North School. Robertson Road, Robertson Road School. Pukeora Forest, Public School. Viscount Street, Viscount School. Pukemiro, Public School. Mangere East- Pungarehu, Primary School. Corner Massey and Hain Avenue, Anglican Church Hall. Raetihi, Public School. Raglan Street, Kingsford School. Raglan, Town Hall. Vine Street, Sutton Park School. Rahotu, Primary School. Manunui, Public School. Ramanui, Ramanui Public School. Manurewa- Ranana, Public School, Dr Pickering Avenue, Leabank Primary School. Rangiriri, Public School. Greenmeadows Avenue, Intermediate School. Rata, Memorial Hall.