Civil Rights and Asian Americans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reenactment Program

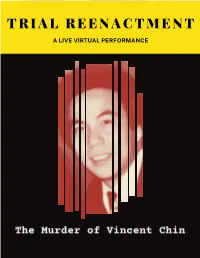

T R I A L R E E N A C T M E N T A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida WITH ITS COHOSTS The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of Tampa Bay The Greater Orlando Asian American Bar Association The Jacksonville Asian American Bar Association PRESENT THE MURDER OF VINCENT CHIN ORIGINAL SCRIPT BY THE ASIAN AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK VISUALS BY JURYGROUP TECHNOLOGY SUPPORT BY GREENBERG TRAURIG, PA WITH MARIA AGUILA ONCHANTHO AM VANESSA L. CHEN BENJAMIN W. DOWERS ZARRA ELIAS TIMOTHY FERGUSON JACQUELINE GARDNER ALLYN GINNS AYERS E.J. HUBBS JAY KIM GREG MAASWINKEL MELISSA LEE MAZZITELLI GUY KAMEALOHA NOA ALICE SUM AND THE HONORABLE JEANETTE BIGNEY THE HONORABLE HOPE THAI CANNON THE HONORABLE ANURAAG SINGHAL ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY DIRECTED BY PRODUCED BY ALLYN GINNS AYERS BERNICE LEE SANDY CHIU ABOUT APABA SOUTH FLORIDA The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida (APABA) is a non-profit, voluntary bar organization of attorneys in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties who support APABA’s objectives and are dedicated to ensuring that minority communities are effectively represented in South Florida. APABA of South Florida is an affiliate of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (“NAPABA”). All members of APABA are also members of NAPABA. APABA’s goals and objectives coincide with those of NAPABA, including working towards civil rights reform, combating anti-immigrant agendas and hate crimes, increasing diversity in federal, state, and local government, and promoting professional development. The overriding mission of APABA is to combat discrimination against all minorities and to promote diversity in the legal profession. -

From Nationalism to Migrancy: the Politics of Asian American Transnationalism 1 Kent A

Communication Law Review From Nationalism to Migrancy: The Politics of Asian American Transnationalism 1 Kent A. Ono, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign Following the Tiananmen Square massacre in China, more than a decade of anti-Chinese sentiment helped to create a post-Cold War hot-button environment. The loss of the Soviet bloc as a clear and coherent international opponent/competitor was followed by the construction of China as the United States' new most significant communist adversary. Hong Kong's return to China; Taiwan's promised return; China's one child policy; news reports of human rights abuses; and China's growing economic strength were all precursors to an environment of anti- Chineseness, the likes of which, as Ling-Chi Wang has suggested, had not existed since that surrounding the late nineteenth-and early twentieth-century Chinese Exclusion era. 2 These geopolitical concerns over China's threat to U.S. world dominance affected Asian Americans and Asian immigrants in the United States. Asian Americans such as John Huang and Wen Ho Lee, targeted for having engaged in allegedly traitorous activities, were, in effect, feeling the heat resulting from increasingly tense U.S./China relations. The frenzied concern over China and the potential danger Chinese Americans posed to the nation state, however, ended suddenly with 9/11. Where China figured prominently on nightly news, in headlines, and in federal intelligence, 9/11 instantaneously shifted the government, military, and media's focus of concern. First came Afghanistan, then Iraq. Since then, Indonesia, North Korea, Iran, and Libya all have been cited as possible adversaries in relation to 9/11. -

California Cadet Corps Curriculum on Citizenship

California Cadet Corps Curriculum on Citizenship “What We Stand For” C8B: Great Americans Updated 20 NOV 2020 Great Americans • B1. Native American Warriors • B2. Military Nurses • B3. Suffragettes • B4. Buffalo Soldiers • B5. 65th IN Regiment “Borinqueneers” • B6. Lafayette Flying Corps • B7. Doolittle Raiders • B8. Navajo Code Talkers • B9. Tuskegee Airmen • B10. African American Units in World War • B11. World War II Nisei Units NATIVE AMERICAN WARRIORS OBJECTIVES DESIRED OUTCOME (Followership) At the conclusion of this training, Cadets will be able to describe groups who have sacrificed for the benefit of the United States despite challenges and obstacles. Plan of Action: 1. Define the warrior tradition and how that motivates Native Americans to serve their country today. 2. Describe how Native American communities support their soldiers and veterans through culture and ceremonies. Essential Question: How have Native Americans contributed to the United States military, and how does their community support and influence their contribution? The Warrior Tradition What is the warrior tradition? Sitting Bull, of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux, said: “The warrior, for us, is one who sacrifices himself for the good of others. His task is to take care of the elderly, the defenseless, those who cannot provide for themselves, and above all, the children – the future of humanity.” Being a warrior is more than about fighting it is about service to the community and protection of your homeland. (WNED-TV & Florentine Films/Hott Productions, 2019) The Warrior Tradition Use this link to play The Warrior Tradition https://www.pbs.org/wned/warrior-tradition/watch/ Check on Learning 1. Name a symbol of Native American tradition that you still see used in Native American culture today. -

The Invention of Asian Americans

The Invention of Asian Americans Robert S. Chang* Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 947 I. Race Is What Race Does ............................................................................................ 950 II. The Invention of the Asian Race ............................................................................ 952 III. The Invention of Asian Americans ....................................................................... 956 IV. Racial Triangulation, Affirmative Action, and the Political Project of Constructing Asian American Communities ............................................ 959 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 964 INTRODUCTION In Fisher v. University of Texas,1 the U.S. Supreme Court will revisit the legal status of affirmative action in higher education. Of the many amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs filed, four might be described as “Asian American” briefs.2 * Copyright © 2013 Robert S. Chang, Professor of Law and Executive Director, Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality, Seattle University School of Law. I draw my title from THEODORE W. ALLEN, THE INVENTION OF THE WHITE RACE, VOL. 1: RACIAL OPPRESSION AND SOCIAL CONTROL (1994), and THEODORE W. ALLEN, THE INVENTION OF THE WHITE RACE, VOL. 2: THE ORIGIN OF RACIAL OPPRESSION IN ANGLO AMERICA (1997). I also note the similarity of my title to Neil Gotanda’s -

Blackface Behind Barbed Wire

Blackface Behind Barbed Wire Gender and Racial Triangulation in the Japanese American Internment Camps Emily Roxworthy THE CONFUSER: Come on, you can impersonate a Negro better than Al Jolson, just like you can impersonate a Jap better than Marlon Brando. [...] Half-Japanese and half-colored! Rare, extraordinary object! Like a Gauguin! — Velina Hasu Houston, Waiting for Tadashi ([2000] 2011:9) “Fifteen nights a year Cinderella steps into a pumpkin coach and becomes queen of Holiday Inn,” says Marjorie Reynolds as she applies burnt cork to her face [in the 1942 filmHoliday Inn]. The cinders transform her into royalty. — Michael Rogin, Blackface, White Noise (1996:183) During World War II, young Japanese American women performed in blackface behind barbed wire. The oppressive and insular conditions of incarceration and a political climate that was attacking the performers’ own racial status rendered these blackface performances somehow exceptional and even resistant. 2012 marked the 70th anniversary of the US government’s deci- sion to evacuate and intern nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast. The mass incarceration of Issei and Nisei in 1942 was justified by a US mindset that conflated every eth- nic Japanese face, regardless of citizenship status or national allegiance, with the “face of the TDR: The Drama Review 57:2 (T218) Summer 2013. ©2013 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 123 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00264 by guest on 01 October 2021 enemy.”1 While this racist reading of the Japanese (American) face has been widely condemned in the intervening 70 years, the precarious semiotics of Japanese ethnicity are remarkably pres- ent for contemporary observers attempting to apprehend the relationship between a Japanese (American) face and blackface. -

Before Pearl Harbor 29

Part I Niseiand lssei Before PearlHarbor On Decemb er'7, 194L, Japan attacked and crippled the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. Ten weeks later, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 under which the War De- partment excluded from the West Coast everyone of Japanese ances- try-both American citizens and their alien parents who, despite long residence in the United States, were barred by federal law from be- coming American citizens. Driven from their homes and farms and "relocation businesses, very few had any choice but to go to centers"- Spartan, barrack-like camps in the inhospitable deserts and mountains of the interior. * *There is a continuing controversy over the contention that the camps "concentration were camps" and that any other term is a euphemism. The "concentration government documents of the time frequently use the term camps," but after World War II, with full realization of the atrocities committed by the Nazis in the death camps of Europe, that phrase came to have a very different meaning. The American relocation centers were bleak and bare, and life in them had many hardships, but they were not extermination camps, nor did the American government embrace a policy of torture or liquidation of the "concentration To use the phrase camps summons up images ethnic Japanese. "relo- ,and ideas which are inaccurate and unfair. The Commission has used "relocation cation centers" and camps," the usual term used during the war, not to gloss over the hardships of the camps, but in an effort to {ind an historically fair and accurate phrase. -

World War Ii Internment Camp Survivors

WORLD WAR II INTERNMENT CAMP SURVIVORS: THE STORIES AND LIFE EXPERIENCES OF JAPANESE AMERICAN WOMEN Precious Vida Yamaguchi A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Ph.D., Advisor Sherlon Pack-Brown, Ph.D. Graduate Faculty Representative Lynda D. Dixon, Ph.D. Lousia Ha, Ph.D. Ellen Gorsevski, Ph.D. © 2010 Precious Vida Yamaguchi All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 required all people of Japanese ancestry in America (one-eighth of Japanese blood or more), living on the west coast to be relocated into internment camps. Over 120,000 people were forced to leave their homes, businesses, and all their belongings except for one suitcase and were placed in barbed-wire internment camps patrolled by armed police. This study looks at narratives, stories, and experiences of Japanese American women who experienced the World War II internment camps through an anti-colonial theoretical framework and ethnographic methods. The use of ethnographic methods and interviews with the generation of Japanese American women who experienced part of their lives in the United State World War II internment camps explores how it affected their lives during and after World War II. The researcher of this study hopes to learn how Japanese American women reflect upon and describe their lives before, during, and after the internment camps, document the narratives of the Japanese American women who were imprisoned in the internment camps, and research how their experiences have been told to their children and grandchildren. -

Crystal City Family Internment Camp Brochure

CRYSTAL CITY FAMILY INTERNMENT CAMP Enemy Alien Internment in Texas CRYSTAL CITY FAMILY during World War II INTERNMENT CAMP Enemy Alien Internment in Texas Acknowledgements during World War II The Texas Historical Commission (THC) would like to thank the City of Crystal City, the Crystal City Independent School District, former Japanese, German, and Italian American and Latin American internees and their families and friends, as well as a host of historians who have helped with the preparation of this project. For more information on how to support the THC’s military history program, visit thcfriends.org/donate. This project is assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the THC and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION 08/20 “Inevitably, war creates situations which Americans would not countenance in times of peace, such as the internment of men and women who were considered potentially dangerous to America’s national security.” —INS, Department of Justice, 1946 Report Shocked by the December 7, 1941, Empire came from United States Code, Title 50, Section 21, of Japan attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii that Restraint, Regulation, and Removal, which allowed propelled the United States into World War II, one for the arrest and detention of Enemy Aliens during government response to the war was the incarceration war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Proclamation of thousands No. 2525 on December 7, 1941 and Proclamations No. -

Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric LuMing Mao Morris Young Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Mao, LuMing and Young, Morris, "Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric" (2008). All USU Press Publications. 164. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/164 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS REPRESENTATIONS Doing Asian American Rhetoric edited by LUMING MAO AND MORRIS YOUNG UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2008 Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Cover design by Barbara Yale-Read Cover art, “All American Girl I” by Susan Sponsler. Used by permission. ISBN: 978-0-87421-724-7 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-87421-725-4 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Representations : doing Asian American rhetoric / edited by LuMing Mao and Morris Young. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-87421-724-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-87421-725-4 (e-book) 1. English language--Rhetoric--Study and teaching--Foreign speakers. 2. Asian Americans--Education--Language arts. 3. Asian Americans--Cultural assimilation. -

Background to Japanese American Relocation

CHAPTER 2 BACKGROUND TO JAPANESE AMERICAN RELOCATION Japanese Americans Prior to World War II The background to Japanese American relocation extends to the mid-19th century when individuals of Chinese descent first arrived in the Western U.S. to work as mine and railroad laborers (Appendix B). Discrimination against the Chinese arose soon after because of economic (i.e., unfair labor competition) and racial (i.e., claims of racial impurity and injury to western civilization) concerns. Because a significant portion of California’s population was Chinese (i.e., approximately 10% in 1870), California played a key role in this discrimination. In 1882, U.S. President Arthur signed into law the Chinese Exclusion Act that effectively ended Chinese immigration to the U.S. until 1943 when the U.S. was allied with China in World War II (Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, 1997). Individuals of Japanese descent began to emigrate in significant numbers to North America’s West Coast in the late 19th century (Appendix B). They came primarily because of the “push” of harsh economic conditions in Japan and the “pull” of employment opportunities in the U.S., partially created by the loss of the Chinese labor force (Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, 1997). Most of these first generation Japanese or Issei settled in California, Oregon, and Washington where they worked in the agriculture, timber, and fishing industries. In California alone, the number of Japanese immigrants increased from 1,147 in 1890 to 10,151 in 1900 (U.S. Census Office, 1895; 1901). The total Japanese American population in the U.S. -

The Richard Aoki Case: Was the Man Who Armed the Black Panther Party an FBI Informant?

THE RICHARD AOKI CASE: WAS THE MAN WHO ARMED THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AN FBI INFORMANT? by Natalie Harrison A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Wilkes Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a Concentration in History Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Jupiter, Florida April 2013 THE RICHARD AOKI CASE: WAS THE MAN WHO ARMED THE BLACK PANTHERS AN FBI INFORMANT? by Natalie Harrison This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Christopher Strain, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Honors College and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ____________________________ Dr. Christopher Strain ___________________________ Dr. Mark Tunick ____________________________ Dr. Daniel White ____________________________ Dean Jeffrey Buller, Wilkes Honors College ____________ Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, Dr. Strain for being such a supportive, encouraging and enthusiastic thesis advisor – I could not have done any of this had he not introduced me to Richard Aoki. I would also like to thank Dr. Tunick and Dr. White for agreeing to be my second readers and for believing in me and this project, as well as Dr. Hess for being my temporary advisor when I needed it. And finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for all their support and for never stopping me as I rattled on and on about Richard Aoki and how much my thesis felt like a spy movie. -

Man 1Ei'vices, Cal Acauj1 Mracism Toward Confirmed What Americans Ofjapanese Ancestry Have Always Womeb'

• c c November?5 19 3 The National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League Chicago Nikkei hear pledges SENATE BILL S 2216 .. Of support from legislators aDCAOO-1be IIbis Dept. cussioos ClIl bow Asian Matsunaga s .... bmits bill 01 iIunum ftjgbtI held a bear Americans are portrayed in fog at Truriian College 00 media, scbools, ami among av. 9 to hear testimony on labor unions. Former JACL on redress to Senate ~otry and other c:mcerns of Midwest ~ Ross lfa.. the state's 250,000 Asians. raoo warDed the department WASHINGTON-Sen.. Spark M. Matsunaga (l)..Hawaii), with Twenty-tive witnEsses ~ that bigotry agaimt Asian 13 colleagues, introduced S 2116 on Nov. 16. The bill would IeDted statements ClIl immi Americans is 00 the rise implement the reammendations of the Commission on War gration ani ref\Jgee pOlicy, natiooally. time Relocation and Internment of Civilians. employment, educatiOn, • JACL Midwest Director In his remarks, Matsunaga stated that, ''The Commission's censing 01 pn!lewjona1a, Bill Y0I!Ihin0 gave aD histori careful review of wartime records, and its extensive hearings, bealtb and ".man 1eI'Vices, cal acauJ1 mracism toward confirmed what Americans ofJapanese ancestry have always womeb'. __, and care of Asians and drew historic known: 1beevacuationofJapanese Americans from the West the t!IcIerIy. parallels to the current at- Coast and their incarceration in what can only be described as Williani Ware. chief of ~ of tension. In ~ ~ntration camps staff for Mayor Harold Wash cl his statement Yosbi- AmericaJrStyle was not justified by mil iDgton, ~ the bearing no saia tbatprejudice and itary necessity, but was the re;ult of racial prejudice, wartime wftb a statement that diS racism "can be as overt as hysteria, and a historic character failure on the part of our crimination against Asian the killing of Vincent Chin in political leaders .• , Americans or any other Detroit or • subUe as the Matsunaga's speech, delivered late last Thursday evening, group, wWld oot be tolerated denial of a job promotion.