Chapter Eight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expressions of Sovereignty: Law and Authority in the Making of the Overseas British Empire, 1576-1640

EXPRESSIONS OF SOVEREIGNTY EXPRESSIONS OF SOVEREIGNTY: LAW AND AUTHORITY IN THE MAKING OF THE OVERSEAS BRITISH EMPIRE, 1576-1640 By KENNETH RICHARD MACMILLAN, M.A. A Thesis . Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University ©Copyright by Kenneth Richard MacMillan, December 2001 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2001) McMaster University (History) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Expressions of Sovereignty: Law and Authority in the Making of the Overseas British Empire, 1576-1640 AUTHOR: Kenneth Richard MacMillan, B.A. (Hons) (Nipissing University) M.A. (Queen's University) SUPERVISOR: Professor J.D. Alsop NUMBER OF PAGES: xi, 332 11 ABSTRACT .~. ~ This thesis contributes to the body of literature that investigates the making of the British empire, circa 1576-1640. It argues that the crown was fundamentally involved in the establishment of sovereignty in overseas territories because of the contemporary concepts of empire, sovereignty, the royal prerogative, and intemationallaw. According to these precepts, Christian European rulers had absolute jurisdiction within their own territorial boundaries (internal sovereignty), and had certain obligations when it carne to their relations with other sovereign states (external sovereignty). The crown undertook these responsibilities through various "expressions of sovereignty". It employed writers who were knowledgeable in international law and European overseas activities, and used these interpretations to issue letters patent that demonstrated both continued royal authority over these territories and a desire to employ legal codes that would likely be approved by the international community. The crown also insisted on the erection of fortifications and approved of the publication of semiotically charged maps, each of which served the function of showing that the English had possession and effective control over the lands claimed in North and South America, the North Atlantic, and the East and West Indies. -

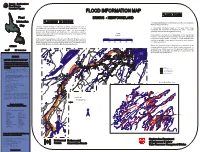

FLOOD INFORMATION MAP FLOOD ZONES Flood BRIGUS - NEWFOUNDLAND

Canada - Newfoundland Flood Damage Reduction Program FLOOD INFORMATION MAP FLOOD ZONES Flood BRIGUS - NEWFOUNDLAND Information FLOODING IN BRIGUS A "designated floodway" (1:20 flood zone) is the area subject to the most frequent flooding. Map Flooding causes damage to personal property, disrupts the lives of individuals and communities, and can be a threat to life itself. Continuing Beth A "designated floodway fringe" (1:100 year flood zone) development of flood plain increases these risks. The governments of une' constitutes the remainder of the flood risk area. This area Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador are sometimes asked to s Po generally receives less damage from flooding. compensate property owners for damage by floods or are expected to find Scale nd solutions to these problems. (metres) No building or structure should be erected in the "designated floodway" since extensive damage may result from deeper and While most of the past flood events on Lamb's Brook in Brigus have been more swiftly flowing waters. However, it is often desirable, and caused by a combination of high flows and ice jams at hydraulic structures may be acceptable, to use land in this area for agricultural or floods can occur due to heavy rainfall and snow melt. This was the case in 0 200 400 600 800 1000 recreational purposes. January 1995 when the Conception Bay Highway was flooded. Within the "floodway fringe" a building, or an alteration to an BRIGUS existing building, should receive flood proofing measures. A variety of these may be used, e.g.. the placing of a dyke around Canada Newfoundland the building, the construction of a building on raised land, or by Brigus the special design of a building. -

Thms Summary for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland And

THMs Summary for Public Water Supplies Water Resources Management Division in Newfoundland and Labrador Community Name Serviced Area Source Name THMs Average Average Total Samples Last Sample (μg/L) Type Collected Date Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook 154.13 Running 72 Feb 25, 2020 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The 68.30 Running 74 Feb 03, 2020 Outflow) Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond 326.50 Running 52 Feb 05, 2020 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 142.25 Running 106 Feb 27, 2020 Intakes) Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond 197.00 Running 51 Feb 18, 2020 Badger Badger Well Field, 2 wells on 5.20 Simple 21 Sep 27, 2018 standby Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond 108.53 Running 25 Feb 12, 2020 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond 0.00 Simple 9 Dec 13, 2018 Barachois Brook Barachois Brook Drilled 0.00 Simple 8 Jun 21, 2019 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as 0.35 Simple 2 Jan 18, 2012 Castors River North) Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well 94.80 Running 48 Mar 10, 2020 Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Sugarloaf Hill Pond 117.83 Running 68 Mar 03, 2020 Bay Roberts Bay Roberts, Rocky Pond 38.68 Running 83 Feb 11, 2020 Spaniard's Bay Bay St. George South Heatherton #1 Well Heatherton 8.35 Simple 7 Dec 03, 2013 (Home Hardware) Bay St. George South Jeffrey's #1 Well Jeffery's (Joe 0.00 Simple 5 Dec 03, 2013 Curnew) Bay St. George South Robinson's #1 Well Robinson's 3.30 Simple 4 Dec 03, 2013 (Louie MacDonald) Bay St. -

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895 An Economic History Reader Collected, Transcribed and Annotated by Christopher Willmore Victoria, British Columbia April 2020 Table of Contents WAYS OF LIFE AND WORK .................................................................................................................. 4 Fog and Foundering (1754) ............................................................................................................................ 4 Hostile Waters (1761) .................................................................................................................................... 4 Imports of Salt (1819) .................................................................................................................................... 5 The Great Fire of St. John’s (1846) ................................................................................................................. 5 Visiting Newfoundland’s Fisheries in 1849 (1849) .......................................................................................... 9 The Newfoundland Seal Hunt (1871) ........................................................................................................... 15 The Inuit Seal Hunt (1889) ........................................................................................................................... 19 The Truck, or Credit, System (1871) ............................................................................................................. 20 The Preparation of -

Héros D'autrefois, Jacques Cartier Et Samuel De Champlain

/ . A. 4*.- ? L I B RAR.Y OF THE U N IVER.SITY Of ILLINOIS B C327d Ill.Hist.aurv g/acques wartJer et Ôan\uel ae wi\an\plait> OUVRAGE DU MEME AUTEUR Parlons français : Petit traité de prononciation Prix, cartonné 50 sous. J\éros a autrejoiOIS acques wartier et Samuef è» ©&an\plcun JOSEPH DUMÂIS fondateur du j|ouYenir patriotique AVEC UNE PRÉFACE DE J.-A. DE PLAINES QUÉBEC Imprimerie de I'Action Sociale Limitée 1913 PRÉFACE âgé Monsieur le professeur Joseph Dumais, déjà avanta- geusement connu au Canada français et en Acadie, par ^ ses cours de diction française et par ses conférences pa- triotiques sur notre histoire, ne pouvait mieux commencer la série des publications du « Souvenir patriotique )) — une société qu'il a fondée et dont le beau nom dit le but excellent, — que par l'histoire, populaire et néanmoins assez riche d'érudition, des deux premiers héros de notre grande histoire. Il convenait, en effet, que le début de cette série fut consacré aux commencements mêmes de notre histoire, d'autant que ces commencements sont d'un intérêt tou- jours empoignant pour nous, et d'une grandeur de con- ception digne de toute admiration. La grandeur de l'histoire, comme d'ailleurs son intérêt, ne dépend pas en effet principalement des masses d'hom- mes qu'elle peut faire mouvoir dans le récit d'événements ordinaires, elle dépend plutôt de la grandeur morale des héros qu'elle met en mouvement, sous l'impulsion d'un puissant idéal, pour la réalisation d'une œuvre d'autant plus élevée et plus glorieuse qu'elle est plus ardue et plus périlleuse. -

Introduction Since Time Immemorial, Human Beings Have Used Narrative

Chapter 1 – Introduction Since time immemorial, human beings have used narrative to help us make sense of our experience of life. From the fireside to the theatre, from the television and silver screen to the more recent manifestations of the virtual world, we have used storytelling as a means of providing structure, order, and coherence to what can otherwise appear an overwhelming infinity of random, unrelated events. In ordering the perceived chaos of the world around us into a structure we can grasp, narrative provides insight and understanding not only of events themselves, but on a more fundamental level, of the very essence of what it means to live as a human being. As the primary means by which historical writing is organized, narrative has attracted a large body of historians and philosophers who have grappled with its impact on our understanding of the past. Underlying their work is the tension between historical writing as a reflection of what took place in the past, and the essence of narrative as a creative, imaginative act. The very structure of Aristotelian narrative, with its causal link between events, its clearly defined beginning, middle and end, its promise of catharsis, its theme or moral, reflects an act of imagination on the part of its author. While an effective narrative first and foremost strives to draw us into its world of story and keep us there until the ending, the primary goal of historical writing, in theory at least, is to increase our understanding about the past. While these two goals are not inherently incompatible, they do not always work in concert. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Entanglements Between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen's

Rogues Among Rebels: Entanglements between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland by Liam Michael O’Flaherty M.A. (Political Science), University of British Columbia, 2008 B.A. (Honours), Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Liam Michael O’Flaherty, 2017 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2017 Approval Name: Liam Michael O’Flaherty Degree: Master of Arts Title: Rogues Among Rebels: Entanglements between Irish Catholics and the Fishermen’s Protective Union of Newfoundland Examining Committee: Chair: Elise Chenier Professor Willeen Keough Senior Supervisor Professor Mark Leier Supervisor Professor Lynne Marks External Examiner Associate Professor Department of History University of Victoria Date Defended/Approved: August 24, 2017 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between Newfoundland’s Irish Catholics and the largely English-Protestant backed Fishermen’s Protective Union (FPU) in the early twentieth century. The rise of the FPU ushered in a new era of class politics. But fishermen were divided in their support for the union; Irish-Catholic fishermen have long been seen as at the periphery—or entirely outside—of the FPU’s fold. Appeals to ethno- religious unity among Irish Catholics contributed to their ambivalence about or opposition to the union. Yet, many Irish Catholics chose to support the FPU. In fact, the historical record shows Irish Catholics demonstrating a range of attitudes towards the union: some joined and remained, some joined and then left, and others rejected the union altogether. -

24 Mar 2020 Page 1 Root AAA #2468, B. ___1600,1,2,3,4,5,6,7

24 Mar 2020 Page 1 Root AAA #2468, b. __ ___ 1600,1,2,3,4,5,6,7. This is a place holder name for general information. - See the sources for this name for citation examples. - Use the 'Occupation' tag for the general source for a person. Put a '.' in the field to ensure the source is printed in reports. The word 'occupation' is translated to 'general source' in the indented book report. I. Alcock AAA #2387. A.James Alcock #16, d. 22 May 1887.8 . He married Mary Ann French #17 (daughter of Joseph French #402 and Welsh bride ... #576). Mary: Mother Welsh. 1. James Alcock #14, b. 16 Jan 1856 in Harbour Grace,8 d. 25 Jun 1895,9 buried in Ch.of England, Harbour Grace. Listed as a fisherman living on Water Street West, St. John's at time of dau. Marion's baptism.10 He married Annie Liza Pike #15, b. 17 Mar 1859 in Mosquito Cove (Bristol's Hope) (daughter of Moses Pike #18 and Patience Cake #19), d. 25 Oct 1932, buried in Ch. of England, Harbour Grace. a. John Alcock #49, b. 28 Jul 1884 in Harbour Grace, buried in Ch of England, Harbour Grace, d. 27 Oct 1905. Never Married. b. Marion (May) Alcock #117, b. 25 Feb 1887 in Harbour Grace,11 baptized 29 Apr 1887,11 d. 25 Mar 1965,12 buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, St. John's,12 occupation .13 . [CR] Marion and Harold lived on Water Street, Harbour Grace. [MGF] Postcard from Hubert Garland to Marion (May) in 1914 was addressed to Ships Head. -

Kittiwake/Gander-New-Wes-Valley Region

Regional Profile of the Kittiwake Region May 2013 Prepared by: Janelle Skeard, Jen Daniels, Ryan Gibson and Kelly Vodden Department of Geography, Memorial University Introduction The Kittiwake/Gander – New-Wes-Valley region is located on the north eastern coast of the Island portion of Newfoundland and Labrador. This region is delineated by the Regional Economic Development Zone (Kittiwake) and the provincial Rural Secretariat region (Gander – New-Wes -Valley) (Figure 1), which have closely overlapping jurisdictions. The region consists of approximately 119 communities, spanning west to Lewisporte, east to Charlottetown, and north to Fogo Island (see Figure 1). Most of these communities are located in coastal areas and are considered to be rural in nature. Only six communities within the region have a population of over 2,000, with Gander being the largest community and the primary service centre for the Kittiwake region. Approximately 20 percent of the regional population resides in the Town of Gander (Rural Secretariat, 2013). The region also encompasses three inhabited islands that are accessible only by ferry: Fogo Island, Change Islands, and St. Brendan's (KEDC, 2007, p.2). Figure 1. Map of Kittiwake/Gander-New-Wes-Valley Region Figure 1: Gander – New-Wes Valley (Map Credit: C. Conway 2008) Regional Profile of the Kittiwake Region Page 2 of 14 Brief History The region’s history is vast. Many of its communities have their own diverse histories, which collectively paint a picture of the past. Aboriginal occupation is the first noted settlement in many parts of the region. Research suggests that 5,000 years ago, what we now call Bonavista Bay was inhabited by Aboriginal peoples who benefited from the region’s abundance of resources such as seal, salmon and caribou. -

The Seventeenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 41 Article 2 2012 The eveS nteenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland Arthur R. Clausnitzer Jr. Barry C. Gaulton Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Clausnitzer, Arthur R. Jr. and Gaulton, Barry C. (2012) "The eS venteenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 41 41, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol41/iss1/2 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol41/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 41, 2012 1 The Seventeenth-Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland Arthur R. Clausnitzer, Jr. and Barry C. Gaulton In 2001 archaeologists working at the 17th-century English settlement at Ferryland, Newfoundland, uncovered evidence of an early structure beneath a mid-to-late century gentry dwelling. A preliminary analysis of the architectural features and material culture from related deposits tentatively identified the structure as a brewhouse and bakery, likely the same “brewhouse room” mentioned in a 1622 letter from the colony. Further analysis of this material in 2010 confirmed the identification and dating of this structure. Comparison of the Ferryland brewhouse to data from both documentary and archaeological sources revealed some unusual features. When analyzed within the context of the original Calvert period settlement, these features provide additional evidence for the interpretation of the initial settlement at Ferryland not as a corporate colony such as Jamestown or Cupids, but as a small country manor home for George Calvert and his family. -

Early Mikmaq Presence in Southern Newfoundland:: an Ethnohistorical Perspective, C.1500-1763

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 04:41 Newfoundland Studies Early Mikmaq Presence in Southern Newfoundland: An Ethnohistorical Perspective, c.1500-1763 Charles A. Martijn Volume 19, numéro 1, spring 2003 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds19_1art03 Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 0823-1737 (imprimé) 1715-1430 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Martijn, C. A. (2003). Early Mikmaq Presence in Southern Newfoundland:: An Ethnohistorical Perspective, c.1500-1763. Newfoundland Studies, 19(1), 44–102. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2003 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Early Mi’kmaq Presence in Southern Newfoundland: An Ethnohistorical Perspective, c.1500-1763 CHARLES A. MARTIJN INTRODUCTION COMPARED WITH MI’KMAQ studies elsewhere, scholarly interest in Newfoundland Mi’kmaq ethnohistory was slow to develop. Of the four Native groups which fre- quented Newfoundland during the historic period, the Beothuk have been the sub- ject of a monumental monograph (Marshall 1996). In contrast, details relating to two others, the Innu (Montagnais) and the historic Inuit, whose range formerly ex- tended into the western and northern regions of the island, constitute largely forgot- ten ethnohistorical chapters (Martijn 1990, 2000).