SOC Spaces of Becoming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

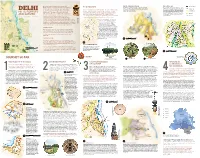

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Jahanpanah Fort, Delhi

Jahanpanah Jahanpanah Fort, Delhi Jahanpanah was a fortified city built by Muhammad bin Tughlaq to control the attacks made by Mongols. Jahanpanah means Refuge of the World. The fortified city has now been ruined but still some portions of the fort can still be visited. This tutorial will let you know about the history of the fort along with the structures present inside. You will also get the information about the best time to visit it along with how to reach the fort. Audience This tutorial is designed for the people who would like to know about the history of Jahanpanah Fort along with the interiors and design of the fort. This fort is visited by many people from India and abroad. Prerequisites This is a brief tutorial designed only for informational purpose. There are no prerequisites as such. All that you should have is a keen interest to explore new places and experience their charm. Copyright & Disclaimer Copyright 2017 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute, or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. -

Report 08-2021

India Gate, Delhi India Gate - The Pride of New Delhi A magnificent archway standing at the crossroads of Rajpath- the India Gate is a war memorial dedicated to the 70000 Indian soldiers who lost their lives in the First World War fighting on behalf of the allied forces. The erstwhile name of India gate is All India War Memorial. Architecture The India Gate was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, the English architect famous for planning a large part of New Delhi . His Royal Highness, the Duke of Connaught laid the foundation stone. Ten years later, Lord Irwin, the then Viceroy of India dedicated the India Gate to the nation. Lutyen was famous for combining classical architecture with traditional Indian elements. A remarkable instance of the classic arch of Lutyen's Delhi Order, the India Gate is a key symbol of New Delhi- the eighth city of Delhi. It bears a strong resemblance to the Arc de Triomphe in France. Though essentially a war memorial, the India Gate also borrows from the Mughal style of creating gateways. The India Gate stands on a base of red Bharatpur stone. The edifice itself is made of red sandstone and granite. An inverted interior dome appears on two square shaped trunks. Imperial signs are inscribed on the cornice. On both the sides of the arch is inscribed the word the word INDIA. The start and end dates of WWI appear on either side of the word. The columns are inscribed with the names of 13516 British and Indian soldiers who had died in the Northwestern Frontier in the Afghan war. -

Law Delegation to India

LAW DELEGATION TO INDIA December 14 - 22, 2018 Program Leader: Ronald Weich Dean, University of Baltimore School of Law Law Delegation to India Prepared by WORLDWIDE ADVENTURES | 1 Dear Friends, Alumni, and Colleagues, As Dean of the University of Baltimore School of Law, I am pleased to invite you to join a delegation of lawyers I will lead for a professional and cultural program in India from December 14 - 22, 2018. Our delegation will explore India’s legal system through a series of meetings, site visits and informal exchanges. Our goal is to learn about India’s legal institutions, including its courts, law schools and bar associations. We will also explore collaborations with Indian universities, law firms and non-governmental organizations. In addition to the professional visits, we will enjoy authentic and immersive cultural activities in Delhi, Jaipur, and Agra. Seasoned guides will accompany the delegation to allow us to fully experience the extraordinary culture, sites and people of India. I am attaching a detailed schedule of activities for your review. Our delegation will meet in Delhi on Saturday December 15 and depart on December 22, 2018. The cost per delegate is $2550. This includes all transportation within India, all meetings and cultural activities as outlined in the schedule, deluxe accommodations based on double or twin occupancy, most meals, professional travel manager and expert guides, pre-departure preparation, and 24-hour emergency support during travel. Delegation members are encouraged to bring their spouses or other guests. Single occupancy accommodations are available for an additional charge of $990. If you have questions regarding the program, I encourage you to contact me or Balu Menon at the Worldwide Adventures India office at 856-885-3006 or [email protected]. -

Film Shooting Manual for Shooting of Films in Delhi

FILM SHOOTING MANUAL FOR SHOOTING OF FILMS IN DELHI Delhi Tourism Govt. of NCT of Delhi 1 Message The capital city, Delhi, showcases an ancient culture and a rapidly modernizing country. It boasts of 170 notified monuments, which includes three UNESCO World Heritage Sites as well as many contemporary buildings. The city is a symbol of the country’s rich past and a thriving present. The Capital is a charming mix of old and new. Facilities like the metro network, expansive flyovers, the swanky airport terminal and modern high- rise buildings make it a world-class city. Glancing through the past few years, it is noticed that Bollywood has been highly responsive of the offerings of Delhi. More than 200 films have been shot here in the past five years. Under the directives issued by Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of I & B, the Govt. of NCT of Delhi has nominated Delhi Tourism & Transportation Development Corporation Ltd. as the nodal agency for facilitating shooting of films in Delhi and I have advised DTTDC to incorporate all procedures in the Manual so that Film Fraternity finds it user- friendly. I wish Delhi Tourism the best and I am confident that they will add a lot of value to the venture. Chief Secretary, Govt. of Delhi 2 Message Delhi is a city with not just rich past glory as the seat of empire and magnificent monuments, but also in the rich and diverse culture. The city is sprinkled with dazzling gems: captivating ancient monuments, fascinating museums and art galleries, architectural wonders, a vivacious performing-arts scene, fabulous eateries and bustling markets. -

Popular Culture, Migrant Youth, and the Making of 'World Class' Delhi

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Aesthetic Citizenship: Popular Culture, Migrant Youth, and the Making of 'World Class' Delhi Ethiraj Gabriel Dattatreyan University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Dattatreyan, Ethiraj Gabriel, "Aesthetic Citizenship: Popular Culture, Migrant Youth, and the Making of 'World Class' Delhi" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1037. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1037 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1037 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aesthetic Citizenship: Popular Culture, Migrant Youth, and the Making of 'World Class' Delhi Abstract Delhi has nearly doubled in population since the early 1990s due to in-migration (censusindia.gov, 2011). These migrants, like migrants around the world, strive to adapt to their new surroundings by producing themselves in ways which make them socially, economically, and politically viable. My project examines how recent international and intranational immigrant youth who have come to Delhi to partake in its economic possibilities and, in some cases, to escape political uncertainty, are utilizing globally circulating popular cultural forms to make themselves visible in a moment when the city strives to recast its image as a world class destination for roaming capital (Roy, 2011). I focus on two super diverse settlement communities in South Delhi to explore the citizenship making claims of immigrant youth who, to date, have been virtually invisible in academic and popular narratives of the city. Specifically, I follow three groups of ethnically diverse migrant youth from these two settlement communities as they engage with hip hop, a popular cultural form originating in Black American communities in the 1970s (Chang, 2006; Morgan, 2009; Rose, 1994). -

Your Itinerary

YOU’RE CORDIALLY INVITED TO JOIN THE WORLD AFFAIRS COUNCIL OF PHILADELPHIA & COOPERATING COUNCILS ON A CULTURAL & WILDLIFE ADVENTURE TO INDIA TIMELESS LAND OF THE TAJ MAHAL & WILD TIGERS NOVEMBER 6 TO 18, 2021 . YOUR ITINERARY DAYS 1/2 ~ SATURDAY/SUNDAY ~ NOVEMBER 6/7 PHILADELPHIA/EN ROUTE Your journey begins as you board your overnight flight to Delhi, via Doha. (Meals Aloft) DAY 3 ~ MONDAY ~ NOVEMBER 8 DELHI Upon arrival at the Delhi Airport (1:55 AM per the current schedule), you will be transported to your hotel where you can enjoy a good night’s sleep. Spend this morning acclimating yourself to your new time zone and in the afternoon, explore one of the most fascinating cities in the world. India’s capital and political hub is an ancient city that has something for everyone. Settled seven times over the centuries, the city has grown in a way that reflects its past, while retaining its cosmopolitan flavor. Delhi is India’s showcase: Be it architecture, religion, shopping, or culture―everything is available here and waiting to be discovered. Venture off to Old Delhi for a visit to Jama Masjid, India’s largest mosque, with a courtyard capable of holding 25,000 devotees. Built in 1644, it was the last in the series of architectural indulgences of Shah Jahan, the Mughal emperor who also built the Taj Mahal and the Red Fort. The highly decorative mosque has three great gateways, four towers, and two 135-foot- high minarets constructed of strips of red sandstone and white marble. Visitors should dress respectfully (no shorts, miniskirts, tank tops etc.). -

Evolution of Delhi Architecture and Urban Settlement Author: Janya Aggarwal Student at Sri Guru Harkrishan Model School, Sector -38 D, Chandigarh 160009 Abstract

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 11, Issue 10, October-2020 862 ISSN 2229-5518 Evolution of Delhi Architecture and Urban Settlement Author: Janya Aggarwal Student at Sri Guru Harkrishan Model School, Sector -38 D, Chandigarh 160009 Abstract Delhi remains one of the oldest surviving cities in the world today. It is in fact, an amalgam of eight cities, each built in a different era on a different site – each era leaving its mark, and adding character to it – and each ruler leaving a personal layer of architectural identity. It has evolved into a culturally secular city – absorbing different religions, diverse cultures, both foreign and indigenous, and yet functioning as one organic. When one thinks of Delhi, the instant architectural memory that surfaces one’s mind is one full of haphazard house types ranging from extremely wealthy bungalows of Lutyens’ Delhi to very indigenous bazaar-based complex settlements of East Delhi. One wonders what role does Architecture in Delhi have played or continue to assume in deciding the landscape of this ever changing city. Delhi has been many cities. It has been a Temple city, a Mughal city, a Colonial and a Post-Colonial city.In the following research work the development of Delhi in terms of its architecture through difference by eras has been described as well as the sprawl of urban township that came after that. The research paper revolves around the architecture and town planning of New Delhi, India. The evolution of Delhi from Sultanate Era to the modern era will provide a sense of understanding to the scholars and the researchers that how Delhi got transformed to New Delhi. -

Conservation & Heritage Management

Chapter – 7 : Conservation & Heritage Management IL&FS ECOSMART Chapter – 7 Conservation & Heritage Management CHAPTER - 7 CONSERVATION & HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 7.1 INTRODUCTION Heritage Resource Conservation and Management imperatives for Delhi The distinctive historical pattern of development of Delhi, with sixteen identified capital cities1 located in different parts of the triangular area between the Aravalli ridge and the Yamuna river, has resulted in the distribution of a large number of highly significant heritage resources, mainly dating from the 13th century onwards, as an integral component within the contemporary city environment. (Map-1) In addition, as many of these heritage resources (Ashokan rock edict, two World Heritage Sites, most ASI protected monuments) are closely associated with the ridge, existing water systems, forests and open space networks, they exemplify the traditional link between natural and cultural resources which needs to be enhanced and strengthened in order to improve Delhi’s environment. (Map -2) 7.1.1 Heritage Typologies – Location and Significance These heritage resources continue to be of great significance and relevance to any sustainable development planning vision for Delhi, encompassing a vast range of heritage typologies2, including: 1. Archaeological sites, 2. Fortifications, citadels, different types of palace buildings and administrative complexes, 3. Religious structures and complexes, including Dargah complexes 4. Memorials, funerary structures, tombs 5. Historic gardens, 6. Traditional networks associated with systems of water harvesting and management 1 Indraprastha ( c. 1st millennium BCE), Dilli, Surajpal’s Surajkund, Anangpal’s Lal Kot, Prithviraj Chauhan’s Qila Rai Pithora, Kaiquabad’s Khilokhri, Alauddin Khilji’s Siri, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq’s Tughlaqabad, Muhammad Bin Tughlaq’s Jahanpanah, Firoz Shah Tughlaq’s Firozabad, Khizr Khan’s Khizrabad, Mubarak Shah’s Mubarakabad, Humayun’s Dinpanah, Sher Shah Suri’s Dilli Sher Shahi, Shah Jehan’s Shahjehanabad, and Lutyen’s New Delhi. -

The DILLI HAAT Provides the Ambience of a Traditional Rural Haat Or Village Market, but One Ssuited for More Contemporary Needs

GlobalBuilds Savouring India! The DILLI HAAT provides the ambience of a traditional Rural Haat or village market, but one ssuited for more contemporary needs. Here one sees a synthesis of crafts, food ad cultural activity. DILLI HAAT transports you to the magical world of Indian art and heritage presented through a fascinating panorama of craft, cuisine and cultural activities. The word Haat refers to a weekly market in rural, semi- urban and sometimes even urban India. While the village haat is mobile, flexible arrangement, here it is crafts persons who are mobile. The DILLI HAAT boasts of nearly 200 craft stalls selling native, utilitarian and ethnic products from all over the country. The Food and Craft Bazar is a treasure house of Indian culture, handicrafts and ethnic cuisine. A unique bazaar, in the heart of the city, it displays the richness of Indian culture on a permanent basis. It is a place where one can unwind in the evening and relish a wide variety of cuisine without paying the exhorbitant rates. Step inside the complex for an altogether delightful experience for either buying inimitable ethnic wares, savouring the delicacies of different states or by simply relaxing in the evening with friends and your family. Delhi Haat is the place where you can find the food of most of the Indian States. Come stimulate your appetite in a typical ambience. Savour specialties of different states. The Makki Ki Roti and Sarson Ka Sag of Punjab; Momos from Sikkim; Chowmein from Mizoram; Dal - Bati Choorma from Rajasthan; Shrikhand, Pao-Bhaji and Puram Poli of Maharashtra; Macher Jhol from Bengal; Wazwan, the ceremonial Kashmiri feast; Idli, Dosa and Uttapam of South Indian and Sadya, the traditional feast of Kerala, all are available under one roof. -

The Art and Culture of Northern India

The Art and Culture of Northern India November 3-16, 2020 With Elizabeth Hornor, Ingram Senior Director of Education, and Professor Joyce Flueckiger, Department of Religion Trip cost per person (based on a group of 10 trav- Included in cost of the trip: • Hotels elers) • Daily breakfasts, six lunches, • USD $7,530 (shared room) and seven dinners (including • Single room supplement: USD $1,800 non-alcoholic beverages) • Internal flights and travel A nonrefundable deposit of $3,835 is due March 6. • Services of an accompany- ing English-speaking tour Museum Donation manager A separate donation of $300, payable by check, should be • All tips and gratuities (ex- mailed to: cept tour manager) Michael C. Carlos Museum • Plane side pick-up and assis- Attn: Jennifer Kirker tance at Delhi International 571 S. Kilgo Circle airport Atlanta, GA 30322 • Mutiny Walk in Delhi • Diwali celebrations at a pri- vate home in Udaipur Medical Cancellation Air Travel • Indian painting atelier in Insurance • Flights to and from India Udaipur must be booked by the trav- • Monument entrance and Medical cancellation insurance eler and are not included in camera fees will allow you to cancel your trip the cost of the trip • Train tickets for Agra/Delhi for medical purposes and will • For internal flights (included in Executive Class cover the traveler’s immediate in the cost of the trip), the • Complimentary bottled family, including parents, sib- checked baggage allowance water and soft beverages of lings, and children who are not is 25 kg per person. The your choice in all vehicles traveling. cabin baggage allowance is • Greeting and assistance at .7 kg per person.