Manuel Antonio Dominguez Salas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darmstadt Summer Course 14 – 28 July 2018

DARMSTADT SUMMER COURSE 14 – 28 JULY 2018 PREFACE 128 – 133 GREETINGS 134 – 135 COURSES 136 – 143 OPEN SPACE 144 – 145 AWARDS 146 – 147 DISCOURSE 148 – 151 DEFRAGMENTATION 152 – 165 FESTIVAL 166 – 235 TEXTS 236 – 247 TICKETS 248 For credits and imprint, please see the German part. For more information on the events, please see the daily programs or visit darmstaedter-ferienkurse.de CONTENTS A TEMPORARY This “something” is difficult to pin down, let alone plan, but can perhaps be hinted at in what we see as our central COMMUNITY concern: to form a temporary community, to try to bring together a great variety of people with the most varied Dr. Thomas Schäfer, Director of the International Music Institute Darmstadt (IMD) and Artistic Director of the Darmstadt Summer Course backgrounds and different types of prior knowledge, skills, expectations, experience and wishes for a very limited, yet Tradition has it that Plato bought the olive grove Akademos also very intense space of time. We hope to foster mutual around 387 BC and made it the first “philosophical garden”, understanding at the same time as inviting people to engage a place to hold a discussion forum for his many pupils. in vigorous debate. We are keener than ever to pursue a Intuitively, one imagines such a philosophical garden as discourse with an international community and discuss the follows: scholars and pupils, experts and interested parties, music and art of our time. We see mutual courtesy and fair connoisseurs and enthusiasts, universalists and specialists behavior towards one another as important, even fundamental come together in a particular place for a particular length preconditions for truly imbuing the spirit of such a temporary of time to exchange views, learn from one another, live and community with the necessary positive energy. -

Julio Estrada

portadilla índice index Presentación El proyecto Presentación El proyecto 11 Itinerarios del sonido 79 Mapa como proyecto fronterizo Mapa Itinerarios del sonido Los artistas como proyecto fronterizo Los artistas Miguel Álvarez Fernández y María Bella 81 Vito Acconci 99 Jorge Eduardo Eielson Reflexiones en torno al proyecto 109 Julio Estrada Reflexiones en torno al proyecto 113 Luc Ferrari 27 Madrid, ciudad ausente 119 Bill Fontana Madrid, the absent city Estrella de Diego 125 Susan Hiller 41 Sonido, materia, espacio 133 Christina Kubisch Sound, matter, space 141 Fernando Millán José Manuel Costa 153 Kristin Oppenheim 55 Ecos y reflexiones de la ciudad: una aproximación a Itinerarios 157 João Penalva del sonido. 163 Adrian Piper Echoes and reflections on the city: an approach to ‘Itinerarios del Sonido’. 169 Francisco Ruiz de Infante José Iges 179 Daniel Samoilovich 185 Trevor Wishart 191 Espacio de documentación Espacio de documentación 196 Comisarios Comisarios 199 Créditos y agradecimientos Créditos y agradecimientos 6 7 presentación presentation 8 9 Itinerarios del sonido como proyecto fronterizo Itinerarios del sonido como proyecto fronterizo Itinerarios del sonido pretende recrear una y Arena de Félix González Torres. La primera ciudad a través del sonido, escuchando el eco consiste en un pequeño cartel que indica el de diferentes voces, como las de Adrian Piper, título de la obra, An oak tree, y en el que el Luc Ferrari, Fernando Millán, Trevor Wishart, artista crea un juego de preguntas y respuestas Kristin Oppenheim, Susan Hiller, Joao Penalva, por el cual da a entender al público que se Christina Kubisch, Bill Fontana, Vito Acconci, encuentra delante de un roble. -

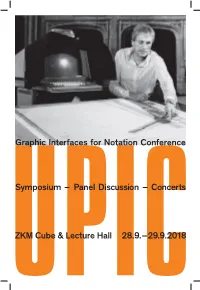

Panel Discussion – Concerts ZKM Cube & Lecture Hall 28.9

Graphic Interfaces for Notation Conference Symposium – Panel Discussion – Concerts ZKM Cube & Lecture Hall 28.9.–29.9.2018 Table of Contents Program Overview 3 Preface 7 Abstracts 8 Program notes 21 Biographies 27 Installation N-Polytope 36 Upcoming Events 38 Symposium Admission Free Installations Admission Free Concerts Entry 10,– / 7,– Free Entry For Participating Artists/Speakers Friday Symposium Session I 14:00 Lecture Hall –18:00 14:00 Cyrille Delhaye Composing by drawing with UPIC: land- marks, archives and traces of composers 15:00 Alain Després The 1980s: UPIC is less than ten years old 16:00 Guy Médigue The Early Days of UPIC 17:00 François-Bernard Mâche UPIC upside down 18:00 Break 19:00– 20:00 Access to installation N-Polytope Concert I 20:00 Cube Julian Scordato Constellations 2014, for graphic sequencer and electronics Vision II 2012, for graphic sequencer and electronics Engi 2017, for graphic sequencer and electronics Julio Estrada eua’on 1980, for UPIC (fixed media version) Marcin Pietruszewski /s v/ 2018 for synthetic voice and computer generated pluriphonic sound François-Bernard Mâche Tithon 1989, fixed media 3 Saturday Symposium Session II 10:00 Lecture Hall –13:00 10:00 Julian Scordato Graphic scores from UPIC to IanniX 11:00 Mark Pilkington Current 9 – Audiovisual Composition 12:00 Chikashi Miyama Developing software for audiovisual interaction 13:00 Break Symposium Session III 14:00 Lecture Hall –18:00 14:00 Marcin Pietruszewski Formalising form across multiple temporal scales 14:30 Julio Estrada The Listening Hand -

Julio Estrada International Contemporary Ensemble Third Coast Percussion Steven Schick, Percussion and Conductor

Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season Composer Portraits Julio Estrada International Contemporary Ensemble Third Coast Percussion Steven Schick, percussion and conductor Thursday, May 16, 8:00 p.m. Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season Composer Portraits Julio Estrada International Contemporary Ensemble Third Coast Percussion Steven Schick, percussion and conductor Thursday, May 16, 8:00 p.m. miqi’cihuatl (2004) Julio Estrada (b. 1943) for voice Tony Arnold, voice ni die saa, E.21f (2013) world premiere, Miller Theatre commission live creation, for ensemble Claire Chase, flute Joshua Rubin, clarinet Jennifer Curtis, violin Daniel Lippel, guitar Ross Karre, percussion Canto naciente (1975-78) for brass octet Peter Evans, trumpet Christopher Coletti, trumpet Brandon Ridenour, trumpet David Byrd-Marrow, horn Danielle Kuhlmann, horn Michael Lormand, trombone David Nelson, trombone Dan Peck, tuba INTERMISSION Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2012-13 | 24th Season Onstage discussion with Julio Estrada and Claire Chase eolo’oolin (1980-1998) for percussion Steven Schick, percussion International Contemporary Ensemble Third Coast Percussion This program runs approximately two hours, including a brief intermission. Major support for Composer Portraits is provided by the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. Composer Portraits is presented with the friendly support of Support for this concert is provided, in part, by the Mexican Cultural Institute of New York. Please note that photography and the use of recording devices are not permitted. Remember to turn off all cellular phones and pagers before tonight’s performance begins. Miller Theatre is wheelchair accessible. Large print programs are available upon request. For more information or to arrange accommodations, please call 212-854-7799. -

To Graphic Notation Today from Xenakis’S Upic to Graphic Notation Today

FROM XENAKIS’S UPIC TO GRAPHIC NOTATION TODAY FROM XENAKIS’S UPIC TO GRAPHIC NOTATION TODAY FROM XENAKIS’S UPIC TO GRAPHIC NOTATION TODAY PREFACES 18 PETER WEIBEL 24 LUDGER BRÜMMER 36 SHARON KANACH THE UPIC: 94 ANDREY SMIRNOV HISTORY, UPIC’S PRECURSORS INSTITUTIONS, AND 118 GUY MÉDIGUE IMPLICATIONS THE EARLY DAYS OF THE UPIC 142 ALAIN DESPRÉS THE UPIC: TOWARDS A PEDAGOGY OF CREATIVITY 160 RUDOLF FRISIUS THE UPIC―EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC PEDAGOGY― IANNIS XENAKIS 184 GERARD PAPE COMPOSING WITH SOUND AT LES ATELIERS UPIC/CCMIX 200 HUGUES GENEVOIS ONE MACHINE— TWO NON-PROFIT STRUCTURES 216 CYRILLE DELHAYE CENTRE IANNIS XENAKIS: MILESTONES AND CHALLENGES 232 KATERINA TSIOUKRA ESTABLISHING A XENAKIS CENTER IN GREECE: THE UPIC AT KSYME-CMRC 246 DIMITRIS KAMAROTOS THE UPIC IN GREECE: TEN YEARS OF LIVING AND CREATING WITH THE UPIC AT KSYME 290 RODOLPHE BOUROTTE PROBABILITIES, DRAWING, AND SOUND TABLE SYNTHESIS: THE MISSING LINK OF CONTENTS COMPOSERS 312 JULIO ESTRADA THE UPIC 528 KIYOSHI FURUKAWA EXPERIENCING THE LISTENING HAND AND THE UPIC AND UTOPIA THE UPIC UTOPIA 336 RICHARD BARRETT 540 CHIKASHI MIYAMA MEMORIES OF THE UPIC: 1989–2019 THE UPIC 2019 354 FRANÇOIS-BERNARD MÂCHE 562 VICTORIA SIMON THE UPIC UPSIDE DOWN UNFLATTERING SOUNDS: PARADIGMS OF INTERACTIVITY IN TACTILE INTERFACES FOR 380 TAKEHITO SHIMAZU SOUND PRODUCTION THE UPIC FOR A JAPANESE COMPOSER 574 JULIAN SCORDATO 396 BRIGITTE CONDORCET (ROBINDORÉ) NOVEL PERSPECTIVES FOR GRAPHIC BEYOND THE CONTINUUM: NOTATION IN IANNIX THE UNDISCOVERED TERRAINS OF THE UPIC 590 KOSMAS GIANNOUTAKIS EXPLORING -

De Xenakis À Nos Jours

De Xenakis à nos jours From Xenakis to the present day Le continuum et son développement en musique et en architecture The continuum and its development in music and architecture Depuis l’Antiquité et le Moyen Âge, transversalement à travers toutes Since Antiquity and the Middle Ages, across all civilizations and religions, les civilisations et les religions, la notion du continuum préoccupe les the concept of continuum has fascinated thinkers. In the early XXth penseurs. Au début du XX° siècle, la théorie de la relativité a bouleversé century, the theory of relativity revolutionized our way of seeing the world notre vision du monde et le discours artistique. as well as artistic discourse. Ce bouleversement correspond aussi aux avancées technologiques This upheaval also coincided with technological advances and the end of et à l’épuisement du modèle romantique. C’est vers le milieu du siècle the Romantic model. During the middle of the last century artists, in turn, dernier que les artistes se sont emparés à leur tour de ces nouvelles transformed these new physical and metaphysical concepts into a tool for notions physiques et métaphysiques pour en faire un outil de création. creation. Iannis Xenakis paved the way both in his music (outside-time/in- Iannis Xenakis donne l’exemple, en musique (structures hors-temps/en- time structures, sound grains ...) and in his architecture (ruled surfaces temps, granularité du son…) comme en architecture (surfaces réglées et and volumetric architecture, polytopes ...). architecture volumétrique, polytopes…). More than ever, today, continuum is at the heart of creative thinking, Le continuum se trouve toujours, et plus que jamais aujourd’hui, au cœur therefore of the arts of the XXIst century. -

La Escucha En 4´33´´ De John Cage; La Escucha Y La Imaginación En Solo Para Uno E Imaginaria De Julio Estrada

Cuadernos de Investigación Musical, julio-diciembre 2021, (13), pp. 76-91 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18239/invesmusic.2021.13.04 ISSN: 2530-6847 La escucha en 4´33´´ de John Cage; la escucha y la imaginación en Solo para uno e Imaginaria de Julio Estrada. Listening in John Cage's 4´33´´; Listening and Imagination in Julio Estrada’s Solo for the Self and Imaginary. Luis Miguel Morales Nieto Investigador independiente [email protected] ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9347-1041 RESUMEN En este trabajo presento las obras 4´33´´ de John Cage y Solo para uno e Imaginaria de Julio Estrada (incluyendo información breve de cada autor) con base en mi experiencia con éstas, algunas comparaciones entre ellas y cómo pienso que podrían experimentarse en colectivo. La primera y segunda creaciones prestan atención a la escucha del entorno, incluyendo nuestros cuerpos, mientras que la segunda y tercera a la imaginación y su escucha. Palabras clave: John Cage, 4´33´´, Julio Estrada, Solo para uno, silencio ABSTRACT In this writing I talk about the pieces John Cage´s 4´33´´ and Julio Estrada’s Solo for the self and Imaginary (including brief information about each author) according to my experience with these, some comparisons between them, and how I think they could be experienced collectively. The first and second creations pay attention to listening to the environment, including our bodies; the second and third to imagination and its listening. Key Words: John Cage, 4´33´´, Julio Estrada, Solo for the Self, Silence Cuadernos de Investigación Musical. -

TEM 75-295 Contents 1..2

VOL.75 NO.295 - JANUARY 2021 ISSN 0040-2982 A QUARTERLY REVIEW OF NEW MUSIC EDITORIAL: NEW MUSIC AND OLD COLONIALS BEYOND THE HORIZON: THE DEPICTION OF TIME IN KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN’S KLANG IAN PARSONS ORCHESTRATION AND PITCH PRECISION IN THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC OF MARC SABAT TAYLOR BROOK A FIELD GUIDE TO SONIC BOTANY: THOUGHTS ABOUT ECO-COMPOSITION MAAYAN TSADKA LABYRINTHS, LIMINALITY AND EKPHRASIS: THE GRAPHICAL IMPETUS IN THE MUSIC OF KENNETH HESKETH THOMAS METCALF THE EAR IS A LABYRINTH: JULIO ESTRADA SEARCHING FOR THE MINOTAUR PABLO SANTIAGO CHIN TWISTING THE ARM OF MICHAEL MAIERHOF: COMPOSER, PERFORMER, CONCERT ORGANISER THOMAS R. MOORE REVIEWS: FIRST PERFORMANCES, CDS, AND BOOKS PROFILE: ADINA IZARRA ARTWORK: MAAYAN TSADKA Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.34.90, on 03 Oct 2021 at 01:58:05, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298220000625 editor Christopher Fox Mission Statement [email protected] As a ‘Quarterly Review of New Music’, TEMPO exists to document the international new music scene while contributing to, and stimulating, current reviews editor Heather Roche debates therein. Its emphasis is on musical developments in our own century, [email protected] as well as on music that came to prominence in the later twentieth century advertising that has not yet received the attention it deserves. Email (UK and rest of the world) [email protected] Subscriptions Email (US) [email protected] TEMPO (ISSN 0040-2982) is published four times a year in January, April, July and October. -

A Depaul Composition Collaboration with Komungo Artist Ik-Soo

A DePaul Composition Collaboration with Koˇmungo artist Ik-Soo Heo A N C I E N T Free anD open to THE PUBlic A P R I L 2 5 – 2 8 E A S T 2 0 1 4 ME E T S C O N T E M P O R A R Y WE S T ANCIENT EaST MEETS CONTEMPORARY WEST APRIL 25–28, 2014 Dear friends, The composition department of the School of Music welcomes you to this special series of concerts celebrating the interaction of cultures as a way of creating new musical works. Faculty member Dr. Seung-Ah Oh proposed this project as a means of connecting DePaul and Korean kŏmungo virtuoso, Ik-Soo Heo. Over the past six months, composers at DePaul, faculty, undergraduate and graduate students alike, have been getting to know this six-string bass zither (an instrument few knew existed) by way of videos, Skype, lecture demonstrations, and experiments with our own practice instrument, generously loaned to us by Ik-Soo Heo. The entire composition department has worked together and apart to compose works that make use of recent musical vocabularies for an instrument that dates from about the fourth century, the kŏmungo, found originally in the kingdom of Goguryeo, the northernmost of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. We are grateful to Ensemble 20+ and its conductor Michael Lewanski for joining us in this endeavor. This remarkable student ensemble enlivens the DePaul new music scene each academic year with six annual concerts of significant, provocative works of new music that enrich the musical lives of performers and composers, and help to create a nurturing environment at DePaul for new creations. -

August 30-31, 2007

Earplay San Francisco Season Concerts 2007-08 Season Herbst Theatre, 7:00 PM Pre-concert talk 6:15 pm Earplay 23: Facets and Lines Monday, November 12, 2007 Peter Maxwell Davies, Barbara White, Liza Lim, Wayne Peterson, Mei-Fang Lin, Mark Applebaum Earplay 23: Unorthodox Journeys Monday, February 11, 2008 Peter Maxwell Davies, Claude Vivier, Morton Feldman, Martha Horst, Aaron Einbond, Richard Festinger Earplay 23: Intricate Inventions Wednesday, May 28, 2008 as part of the San Francisco International Arts Festival Peter Maxwell Davies, Christopher Burns, Salvatore Sciarrino, Beat Furrer Special Performances: Wayne Peterson 80th Birthday Celebration Thursday, September 20, 2007 Knuth Hall San Francisco State University August 30-31, 2007 Festival of New American Music Sonic Bloom of the Central Valley Monday, November 5, 2007 Wayne Peterson 80th Birthday Celebration Monday, November 5, 2007 California State University, Sacramento elcome to an Earplay performance. Our mission is to nurture new chamber music --composition, performance, and audience--all vital components. WEach concert features the renowned members of the Earplay ensemble performing as soloists and ensemble artists, along with special guests. Over twenty-three years, Earplay has made an Earplay enormous contribution to the bay area music community. The Earplay ensemble has performed hundreds of works by more Donald Aird than two hundred composers. Earplay has commissioned an Memorial average of two new works per season, and has presented more than one hundred world premieres. -

Julio Estrada Foto: Ernesto Peñaloza (México 1943)

juliusedimus Julio Estrada foto: ernesto peñaloza (México 1943) Sus estudios se nutren julio estrada de la tradición –Orbón, Boulanger, Conservatoire de Paris– y de la renovación –Messiaen, catálogo - 2014 Lachenmann, Ligeti, Stockhausen y Xenakis. [email protected] Evoluciona desde el minimalismo abierto - Memorias para teclado- colección completa: materiales digitales con partes: a la post-tonalidad - via dropbox, de $900 a $800 usd serie de los Cantos- y al continuo -yuunohui, e.1 Suite (1959-60) piano, 2 pp. ($6) ishini’ioni, eolo’oolin y eua’on’ome. e.5 Memorias para teclado (1971) cualquier teclado a 2 o Recibe encargos de los a 4 manos, acordeón o percusión de teclado, 31 pp. ($28) festivales de Darmstadt, Donaueschingen, Bremen - Siemens, Músicadhoy, e.6 Solo para uno (1972) partitura verbal multilingüe Rassegna di Nuova (español, inglés, francés, italiano, alemán), 32 pp. ($12) Musica, o Radio Nacional de España, Süd West- Rundfunk, International e.9 Canto tejido (1974) piano, 12 pp. ($12) Contemporary Ensemble. e.12 Canto naciente (1975-79) octeto de metales (3 Sus intérpretes: Velia Nieto, Stefano trompetas, 2 cornos, 2 trombones, 1 tuba), partitura, 45 pp. Scodanibbio, Magnus ($42), partes, 44 pp. ($42) Anderson, Ko Ishikawa, Fátima Miranda, David e.17 eolo’oolin (1981-83) seis percusionistas en Núñez, Paul Hübner, Felix del Tredici, Rohan movimiento, partitura, 123 pp. ($100), partes, 309 pp. de Saram, Neue Vocal ($100); CD ($16), DVD ($24) Solisten, Percussions de Strasbourg, Kairos Quartet, Arditti Quartet… e.19 ishini’ioni (1984-90) cuarteto de cuerdas, manuscrito 80 pp. ($42) y partes manuscrito ($42) LosMurmullos festivales del Tage páramo für , e.18a yuunohui’se (1990) violín, manuscrito 18 pp. -

György Ligeti's Melodien, a Work of Transition

Journal of New Music Research ISSN: 0303-3902 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/nnmr19 György Ligeti's melodien, a work of transition Ignacio Baca‐Lobera To cite this article: Ignacio Baca‐Lobera (1991) György Ligeti's melodien, a work of transition, Journal of New Music Research, 20:2, 65-78, DOI: 10.1080/09298219108570578 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09298219108570578 Published online: 03 Jun 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 43 Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=nnmr20 Interface, Vol. 20 (1991), pp. 65-78 0303-3902/91/2002-0065 $3.00 © Swets & Zeitlinger György Ligeti's Melodien, a Work of Transition Ignacio Baca-Lobera ABSTRACT György Ligeti's music underwent a change of style at the end of the 1960's. There was an apparent exhaustion in the syntax of musical elements and their transforma- tion in his works. New elements appeared at that time, and some became less defined. In the oeuvre of a composer whose works share transformation similarities, memory (and musical memory) may be used as a parallel to grasp his musical thought and its evolution. LIGETI'S MUSIC, AESTHETIC AND TECHNIQUE György Ligeti (1923) is now a well-established composer; his music is often performed and recorded. He is considered an important musical figure in the second half of the twentieth century. However, although his aesthetic ideas and methods present very interesting aspects, his music is nevertheless difficult to analyze. Some of Ligeti's large scale works resemble one another closely; the elements (the single components which, in combination, produce textures) and the shapes forming his music are also very similar, and in some cases identical; i.e.