Studies and Reviews N.81

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Static Fishing Around Fish Aggregating Devices (Fads) and Offshore Banks

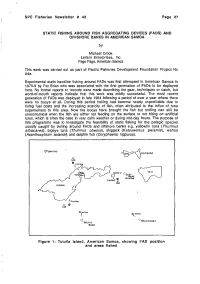

SPC Fisheries Newsletter # 42 Page 27 STATIC FISHING AROUND FISH AGGREGATING DEVICES (FADS) AMD OFFSHORE BANKS IN AMERICAN SAMOA by Michael Crook Leilani Enterprises, Inc Pago Pago, American Samoa This work was carried out as part of Pacific Fisheries Development Foundation Project No 44a. Experimental static handline fishing around FADs was first attempted in American Samoa in 1978-9 by Pat Brian who was associated with the first generation of FADs to be deployed here. No formal reports or records were made describing the gear, techniques or catch, but word-of-mouth reports indicate that this work was mildly successful. The most recent generation of FADs was deployed in late 1984 following a period of over a year where there were no buoys at all. During this period trolling had become nearly unprofitable due to rising fuel costs and the increasing scarcity of fish, often attributed to the influx of tuna superseiners to this area. Now the buoys have brought the fish but trolling can stiil be uneconomical when the fish are either not feeding on the surface or not biting on artificial lures, which is often the case in very calm weather or during mid-day hours. The purpose of this programme was to investigate the feasibility of static fishing for the pelagic species usually caught by trolling around FADs and offshore banks e.g. yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus), skipjack {Katsuwonus pelamis), wahoo (Acanthocybium solandn) and dolphin fish (Coryphaena hippurus). (P SWAINS a lORl^C VOLOSEGA 'E' FAD n 3 miles TA U /-'^Paao sJ AUNU'U V C~?ago| ^o BANK \ , \_^J 20 miles \ / 5 miles" ^ FAD y TUTUILA w^-> ( 3 miles [ 'c' 0 FAD 35 miles 40 miles "SOUTHEAST " SOUTH BANK Figure 1: Tutuila Island, American Samoa, showing FAD position and areas fished PSger?28! SPCi FisherJesrvWews letters #42; Mettibds (arM ;:inaterialsn Oi'NTASSflSDA n&''~\ mtU^/i Slli'^m-i orh"-t The sixteen trips made between December 1984 and April 1985 were aboard the 40 ft. -

Fishing Techniques Used Around Fish Aggregation Devices in French Polynesia

SPC/Fisheries 22/WP.14 27 July 1990 ORIGINAL : FRENCH SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION TWENTY-SECOND REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING ON FISHERIES (Noumea, New Caledonia 6-10 August, 1990) FISHING TECHNIQUES USED AROUND FISH AGGREGATION DEVICES IN FRENCH POLYNESIA by F. Leproux, G. Moarii, S. Yen EVAAM, B.P. 20, Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia 643/90 SPC/Fisheries 22/WP.14 Page 1 FISHING TECHNIQUES USED AROUND FISH AGGREGATION DEVICES IN FRENCH POLYNESIA Mooring FADs in French Polynesian waters, which began in June 1981, has had a favourable impact on local fishermen who, although they were sceptical to begin with, have come to use this assistance increasingly, many of them finding it very helpful. The techniques of fishing around FADs have changed over the years and in 1990 four are still currently in use, while new techniques are constantly being developed and taught in order to obtain better yields. 1. FISHING TECHNIQUES 1.1 Handline fishing Many small boats (3 to 6m) do deep fishing near FADs when a school of tuna is present. The handline is made of nylon line of 130 kg and a tuna hook (cf Diagram no. 1, Plate no. 1). The bait used varies with the season: thus "operu" (Decapterus macarellus), "ature" (Selar crumennhialmus), "numa" (Mulloidichihys samoensis), "marara" (Cysselurus simus), and skipjack fillet (Katsuwonus pelamis) are the most commonly used. The technique consists in placing this bait low down in the school. In order to facilitate the drop of the line, a stone is fixed to it temporarily. When the fisherman considers that he has reached the required depth, he gives the line a sharp jerk upwards which releases the stone and also some crumbs which awake the tunas' appetite. -

Tuna Fishing and a Review of Payaos in the Philippines

Session 1 - Regional syntheses Tuna fishing and a review of payaos in the Philippines Jonathan O. Dickson*1', Augusto C. Nativiclacl(2) (1) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, 860 Arcadia Bldg., Quezon Avenue, Quezon City 3008, Philippines - [email protected] (2) Frabelle Fishing Company, 1051 North Bay Blvd., Navotas, Metro Manila, Philippines Abstract Payao is a traditional concept, which has been successfully commercialized to increase the landings of several species valuable to the country's export and local industries. It has become one of the most important developments in pelagic fishing that significantly contributed to increased tuna production and expansion of purse seine and other fishing gears. The introduction of the payao in tuna fishing in 1975 triggered the rapid development of the tuna and small pelagic fishery. With limited management schemes and strategies, however, unstable tuna and tuna-like species production was experienced in the 1980s and 1990s. In this paper, the evolution and development of the payao with emphasis on the technological aspect are reviewed. The present practices and techniques of payao in various parts of the country, including its structure, ownership, distribution, and fishing operations are discussed. Monitoring results of purse seine/ringnet operations including handline using payao in Celebes Sea and Western Luzon are presented to compare fishing styles and techniques, payao designs and species caught. The fishing gears in various regions of the country for harvesting payao are enumerated and discussed. The inshore and offshore payaos in terms of sea depth, location, designs, fishing methods and catch composi- tion are also compared. Fishing companies and fisherfolk associations involved in payao operation are presented to determine extent of uti- lization and involvement in the municipal and commercial sectors of the fishing industry. -

Hawai'i Pelagic Handline Fisheries: History, Trends, and Current Status

Hawai‘i Pelagic Handline Fisheries: History, Trends, and Current Status - Final Background Document - Prepared for the WESTERN PACIFIC FISHERY MANAGEMENT COUNCIL by Impact Assessment, Inc. Pacific Islands Office [email protected] March 2007 IMPACT ASSESSMENT, INC. Pacific Islands Office 2950 C Pacific Heights Road Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Mr. Paul Dalzell, Senior Scientist Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council 1164 Bishop Street, Suite 1400 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 March 8, 2007 Dear Mr. Dalzell, We are pleased to submit this final report for the project titled Background Document on the Offshore Handline and Shortline Fishery (Phase I). Per WPRFMC Contract 06-WPC-11, the report was previously delivered in draft form for distribution at the Council’s 91st Science and Statistical Committee Meeting, and at the 131st Council Meeting. We would like to express our appreciation for the opportunity to assist the Council in better understanding the history and contemporary status of the offshore handline fleet in the Main Hawaiian Islands. Additional description and analysis of the fleets will be provided in our FY 2007 report to the Pelagic Fisheries Research Program at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Mahalo nui loa for your diligent monitoring of this important project. We look forward to undertaking similar research in support of the Council’s sustainable fisheries management objectives throughout the Western Pacific. Sincerely, Edward W. Glazier, Ph.D. Principal Investigator Acknowledgements We wish to thank and acknowledge the -

Non-Lethal Seal Deterrent in the North East Scotland Handline Mackerel Fishery

Non-Lethal Seal Deterrent in the North East Scotland Handline Mackerel Fishery. A Trial using Targeted Acoustic Startle Technology (TAST) David Whyte, Thomas Götz, Sam F. Walmsley and Vincent M. Janik 1 Contents Project Team ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Funding ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Fishing methods .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Trial Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Data analysis .............................................................................................................................................. 13 Results ....................................................................................................................................................... 15 Discussion ................................................................................................................................................. -

Overfishing Definitions, and Bycatch

WESTERN PACIFIC REGIONAL FISHERY MANAGEMENT COUNCIL MAGNUSON-STEVENS ACT DEFINITIONS AND REQUIRED PROVISIONS OVERFISHING PROVISIONS Amendment 6 (Supplement) to the Fishery Management Plan for the Bottomfish and Seamount Groundfish Fisheries of the Western Pacific Region Amendment 8 (Supplement) to the Fishery Management Plan for the Pelagic Fisheries of the Western Pacific Region Amendment 10 (Supplement) to the Fishery Management Plan for the Crustaceans Fisheries of the Western Pacific Region Including an Environmental Assessment December 20, 2002 Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council 1164 Bishop St., Suite 1400 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Telephone (808) 522-8220 Fax (808) 522-8226 Cover Sheet i Summary On October 11, 1996 the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA) was re-authorized and amended by the Sustainable Fisheries Act (SFA). As a result, the MSA contains new requirements, making it necessary for Fishery Councils to amend all of their existing Fishery Management Plans (FMP) to incorporate these requirements. The Western Pacific Fishery Management Council (Council) developed amendments to its four FMPs to address these requirements, which were published in September 1998 and submitted to the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) for review and approval. NMFS only partially approved the amendments, as described in a Federal Register notification published on April 19, 1999 (64 FR 19067). Among other elements, the overfishing provisions (those required under Section 303(a)(10) and related sections of the MSA, as amended by the SFA) in Amendment 6 to the Bottomfish FMP, Amendment 8 to the Pelagics FMP, and Amendment 10 to the Crustaceans FMP were disapproved. These FMP amendments supplement those partially approved amendments by providing new specifications of overfishing criteria. -

Gillnet Fishing in Macuata, Fiji

GILLNET FISHING IN BACKGROUND OF MACUATA The land and coastal bounda- MACUATA, FIJI ries of the Macuata Province lie between latitude 16°5’S to 16°35’S and longitude 178°50’W INTRODUCTION to 179°45’W, on the second larg- est island of Fiji, called Vanua The purpose of this trip to Fiji Levu. The island of Vanua Levu was to review the effectiveness is composed of three large prov- of the banning of commercial inces: Macuata, Bua and gillnet fishing in Macuata Prov- Cakaudrove. Macuata is made ince on Vanua Levu. We were up of the northern portion of also asked to make recommen- 9th ofby February Esaroma for Ledua, the start of Vanua Levu and five other Integrated Fisheries dations on whether the ban the survey work. Three Fiji Fish- small islands to the north. Management Associate, should be maintained, and to eriesSouth Research Pacific Officers Commission were as- Labasa Town is the capital of advise on any other manage- signedNoumea, as full-time New Caledonia counterparts Macuata Province. ment measures relating to com- to this project. They were mercial and subsistence fishery Apisai Sesewa (team leader), Since Macuata is a dry area (av- in Macuata Province. Saiyasi Yabakivou and Jovesa erage rainfall of 4,050 mm/ Korovulavula. year), it has a climate favourable The gillnet fishing ban was im- for growing sugar cane, and posed by the Macuata chiefs in Considerable support was re- Macuata is one of the leading 1990. Unfortunately, there was ceived from the Fisheries Divi- sugar producers in Fiji. The no survey conducted at this sion, especially the provision of province of Macuata is also time, so no estimates of stock support staff, fishing gear and known for its timber and fish- abundance were available for vessels. -

RECENT USE of FISH AGGREGATING DEVICES in the EASTERN TROPICAL PACIFIC TUNA PURSE-SEINE FISHERY: 1990-1994 (Revised March 1996)

RECENT USE OF FISH AGGREGATING DEVICES IN THE EASTERN TROPICAL PACIFIC TUNA PURSE-SEINE FISHERY: 1990-1994 (Revised March 1996) (This is a revised copy of Administrative Report LJ-95-14) By Wesley A. Armstrong and Charles W. Oliver Southwest Fisheries Science Center P.O. Box 271 La Jolla, California 92038-0271 March 1996 ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT LJ-96-02 Contents Page List of Figures....................................................................................................................................ii List of Tables.................................................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................1 LOGS ...............................................................................................................................................2 FADS................................................................................................................................................4 FAD INVESTIGATIONS: 1990-1992 .............................................................................................6 FAD INVESTIGATIONS: 1993-1994 .............................................................................................7 DOLPHIN-SAFE QUESTIONNAIRE.............................................................................................8 SKIPPER A's FADs: Drifting FADs: Construction and Deployment..........................................................................9 -

Quantifying Fish Escape Behaviour Through Large Mesh Panels

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Dec 20, 2017 Quantifying fish escape behaviour through large mesh panels in trawls based on catch comparision data – model development and a case study from Skagerrak In: ICES (2012) Report of the ICES-FAO Working Group on Fishing Gear Technology and Fish Behaivour (WGFTFB), 23-27 April 2012, Lorient, France. ICES CM 2012/SSGESST:07 Krag, Ludvig Ahm; Herrmann, Bent; Karlsen, Junita Diana Publication date: 2012 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Krag, L. A., Herrmann, B., & Karlsen, J. (2012). Quantifying fish escape behaviour through large mesh panels in trawls based on catch comparision data – model development and a case study from Skagerrak In: ICES (2012) Report of the ICES-FAO Working Group on Fishing Gear Technology and Fish Behaivour (WGFTFB), 23-27 April 2012, Lorient, France. ICES CM 2012/SSGESST:07. Abstract from ICES-FAO Working Group on Fishing Gear Technology and Fish Behaivour (WGFTFB) , Lorient, France, France. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Fish Aggregating Devices in French Polynesia

I' FISH AGGREGATING DEVICES IN FRENCH POLYNESIA BY JACQUES CHABANNE' The use of FADS for the development of tuna fishing in French Polynesia was contemplated in late 70's (Marcille. 1979). The first deployment of FADS was undertaken soon after by the organization in charge of projects for fishery development (Ugolin¡ and Robert, 1982). In the early stages of the FAD project, the objectives of i1 rather general nature, were more speciEically directed to developing surface tuna fishing, i.e. skipjack and yellowfin fishing. The immediate goal was to assist the ¿1rtisiiIi:11 pjack fishery which was experiencing economic difficulties. In the long ryn, the aim is to promote a more industrial type of exploitation, calling for fishing techniques having ¿i high degree of efficiency. Howcvcr, Lifter ;I few years, one is able to observe that a gap exists between the initin1 goals iIIid the actual use of FADs. Concerning surface fishing, spin-offs have remained limited (í1rtis:iniil skipjilck fishery) or non-existent (fishery development). On the other hand, the artisanal handline fishery for deep swimming tunas has proved to he the main user of FADs. The difficultics cncountcrcd in ;itraining the expected goals, particularly in fishery development, bccainc appiircnt from Itic very beginning of the project. They resulted from insufficient knowledge of (he monner in which FADS woIk and, iiiorc spccifi&illy, their efficiency in iiggrcg;\ting fish. Besides, technical problems concerning their durability at sea occurred in the cilse of the first FADs. Both in order to solve tcchIiOlOgici~1issues ancl to cletcrminc the uctual possibilitics of FADs for tuna fishing in k'rench PoLy1icSiit, ii rcsciircli alitl d~velopliiciitprc)griilii1iic has heen unrlcrtnkcn (Anoli. -

(SFITUM). EC Project 02/C132/11/41 Volume 1

Sport Fishing: an informative and economic alternative for tuna fishing in the Mediterranean (SFITUM). EC Project 02/C132/11/41 Volume 1: Legislation SFITUM nº02/C 132/11/41 Final Report December/2004 Vol. I Coordinator – • CEAB-Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) (Dr. A. Gordoa) C/Acc. Sant. Francesc 14 17300 Blanes. Girona-Spain Partners- • Oceanic Development (Dr. Benoît Calliart) Zone Industrielle du Moros 29900 Concarneau- France • AQUASTUDIO (Dr. A. Di Natalle) Via Trapani 6 98121 Messina- Italy • Universidad de Barcelona (UB) Gabinete de Economía del Mar (Dr. R. Franquesa) Av. Diagonal 690 08034 Barcelona- Spain • Federation Internacional de la Pêche Sportive en Mer (FIPS/M) (Mr. M. Ordan) 26 Rue de Belvaux P.O Box 9 L-4504 Oberkorn- Luxemburg • Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) (J.M. de la Serna) Puerto Pesquero s/n Aptdo. de Correos 285 29640 Fuengirola Malaga- Spain SFITUM nº02/C 132/11/41 Final Report December/2004 Vol. I LIST OF PARTICIPANTS • CEAB-CSIC Ana Gordoa Txabi Mina Sergi Nuss MªÀngels Vich • UB Ramón Franquesa Juan Ramón Borrego • OCEANIC Benoît Calliart Laurence Mazaudier • IEO J.M. de la Serna • AQUAESTUDIO Antonio Di Natale • FIPS/M Mr. M. Ordan Collaborators • FMPR (Federación Mediterránea por una Pesca Responsable) Esteban Graupera Ramón Raventós SFITUM nº02/C 132/11/41 Final Report December/2004 Vol. I INDEX INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1. RECREATIONAL SEA -

Anchored Fish Aggregating Devices in Hawaiian Waters

Anchored Fish Aggregating Devices in Hawaiian Waters WALTER M. MATSUMOTO, THOMAS K. KAZAMA, and DONALD C. AASTED Introduction tions was well over 4: 1 in favor of sets tional Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) made around drifting logs as compared Southwest Fisheries Center and the Tunas have long been known to ag with sets made on schools independent PTDF embarked on a joint project to gregate around floating objects such as of logs. test anchored fish aggregating devices in logs, masses of drifting seaweed, debris, While the value of drifting logs to Hawaiian waters in May J977. The proj and other flotsam. Both Japanese and successful seining has been well demon ect was funded largely by PTDF with American fishermen have utilized this strated by these questions, such logs, additional support from NMFS. This knowledge and routinely seek such ob which abound in the western equatorial report covers the procedures and results jects while fishing for skipjack tuna, Pacific, especially in waters north of of the project. Kalsuwonus pelamis, and yellowfln Papua ew Guinea, are only seldom tuna, Thunnus albacares, in the east found around islands in the central Pa Objectives ern and western Pacific (Uda, 1933; cific. Moreover, whenever an occasion The primary objectives of the project Kimura, 1954; McNeely, 1961; Inoueet allog is encountered in the latter areas, were to: 1) Develop and test anchored aI., 1963, 1968). it is available to the local fishermen only fi~h aggregating devices (hereafter called In recent years, the Japanese began for a short time before it drifts off be buoys) in open ocean areas and 2) de seining for skipjack and small yellowfln yond the range of their boats.