S31q Special Evaluation of the Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MLD Brochure

1. Historical Background Local Self Governance, it is mentioned that, to make conducive environment to exercise the sovereignty of people, Tribhuvan Village Development Program that had been decentralization and devolution of authority, sharing of introduced in 1952, with the advent of democracy is responsibility and revenue among central and agencies considered as a milestone in local development. The related to local self governance and, hence, made objectives of the program were as follows: commitment on providing authority and resources to the • Disseminate the methods of increasing agriculture people. To operataionalize the policy of decentralization into production to uplift the living standards of people; practice and to facilitate local level development activities • Construct canal, drinking water well, road, and through local bodies, the ministry has been entrusted with building in people's participative way; great responsibilities. On the basis of the fact as mentioned • Provide social services; above, objectives for Ministry of Local Development have • Raise the awareness among the rural people towards been set. the development by providing training to local village activists, etc. 2 Objectives Nepal has been administratively divided into 14 zones The objectives of the Ministry: and 75 districts in 2018 B.S. Village, Municipal and District o Develop the local self governance system and strengthen Panchayat were formed and developed as local bodies in local bodies as capable, effective and responsible village, municipal and district level respectively. District institutions Administrative Plan of 2031 B.S. had integrated local development and local administration into a single o Develop institutional mechanism and process for the organization and established Chief District Officer as a implementation of local and community development responsible Officer for local development. -

Download Publication

RESEARCH REPORT Emerging Issues of Confict in November 2019 Federalized Context in Nepal 1 EMERGING ISSUES OF CONFLICT IN FEDERALIZED NEPAL Research Report November 2019 ASIAN ACADEMY FOR PEACE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT Emerging Issues of Conflict in Federalized Context in Nepal November 2019 1000 Copies ASIAN ACADEMY Copyright : © FOR PEACE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ISBN : 978-9937-0-6973-1 Research Advisors : Mr. Shiva K Dhungana Mr. Tulasi R Nepal Reacher Team : Leader – Rabindra Bhattarai Member – Rita Bhadra Shrestha Member – Sharad Chandra Neupane Publisher : Asian Academy for Peace, Research and Development Thapagaun, Baneshwor, Kathmandu Email: [email protected] Tel: 015244060 i FOREWORD The research ‘Emerging Issues of Conflict in Federalized Context in Nepal’ has aimed at identifying the issues related to the implementation of the federal restructuring in the country. The research is an outcome of the desk review and field level interviews and focus group discussions in nine districts namely Ilam, Jhapa, Morang, Dhanusha, Mahottari, Makawanpur, Surkhet, Kailali and Rukum West, as well as drawings from a national level interaction held in Kathmandu to disseminate and validate the findings from the field. Asian Academy for Peace, Research and Development (Asian Peace Academy) expresses its sincere gratitude to Kurve Wustrow, Centre for Training and Networking in Non-violence Actions and Civil Society Platform for Peacebuilding and Statebuilding (CSPPS) for their support to undertake this research. A team of researchers collected and analysed the information to draw findings of the study. Therefore, the research is a collaborative effort of the researchers and field level supporting hands. I would like to thank Mr. -

Dormant List for Web Site.Xlsx

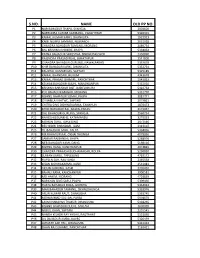

Total Dormant list Nepal Finance Limited SN BranchCode Name MainCode LastTranDate 1 001 NECO INSURANCE LTD 00100100000013000001 03/11/2009 2 001 LAXMAN POUDEL 00100100000129000001 17/03/2013 3 001 BISHNU PD.LAMSAL 00100100000142000001 02/11/2011 4 001 DHARATI SHRESTHA 00100100000159000004 25/01/2011 5 001 NARAYANESWORANANDA BAIDYA 00100100000182000005 04/11/2015 6 001 MADHABENDRA KC 00100100000270000001 10/09/2014 7 001 DHIRAJ & SIDDHI KARK (KUNWAR) 00100100000290000002 16/02/2010 8 001 TISA MANANDHAR 00100100000306000002 23/03/2014 9 001 MACHAMA MANANDHAR 00100100000343000001 29/11/2013 10 001 SABITA NAKARMI 00100100000371000002 06/07/2011 11 001 JAGADISHWOR PARAJULI 00100100000428000001 20/03/2013 12 001 VIVEK AGRAWAL 00100100000432000002 19/06/1905 13 001 NEPAL DEVELOPMENT & EMPLOYMENT PROM 00100100000472000001 01/03/2010 14 001 SANGHA DAS SHRESTHA 00100100000614000002 04/11/2015 15 001 JAMUNA LAXMI PRADHAN 00100100000679000001 21/06/2011 16 001 AMAR LAMA 00100100000698000001 18/03/2012 17 001 GOPI LSHRESTHA 00100100000728000003 06/10/2015 18 001 SHANTI BHATTARAI 00100100000783000003 04/06/2012 19 001 SHIVAS CHAN SHAKA 00100100000854000001 12/08/2014 20 001 JAYANTI LAMACHANE 00100100000882000002 16/06/2014 21 001 SNOW LION FOUNDATION 00100100000905000001 21/04/2016 22 001 TIKA PRASAD SHARMA 00100100000916000001 25/03/2013 23 001 CHITRA K. GAUTAM 00100100000947000001 30/05/2011 24 001 RAMA DEVI SINGH 00100100000990000002 22/03/2013 25 001 RAM BDR PRAJAPATI 00100100001016000002 22/10/2009 26 001 LATA REGMI 00100100001100000001 11/11/2012 -

FINAL PRO=S to *Be

b", -~~~A.• e TRAIN 6N 4PALES, 1N AGUICULTOKUML UAKC FINAL PRO=S to *be United Stateo Agony for International Development . by the Agricultural Development Counil. Inc. October 1, 1976- September 30. i8i (Grant No. AID/A8IA-G-11) shao-er Ong A/D/C' smooate tband Nepal October 1961 TRAINING NEPALESE IN AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT PLANNING CONTENTS Page INTRODUCT I ON Background 1 Objectives 3 Targets 3 Designs 5 Personnel changes 6 TRAINING Degree Training 8 Master 's Level Training 8 Ph.D. Level Training 10 Non-degree Training 11 Training Received Outside Nepal 11 Training Programs Organized in Nepal 13 Estimated Benefit of Training Under this Project Support 15 RESEARCH Research Activities Participated Directly by the ADC Staff 17 Research Activity Financially and Technically Supported by this Project 19 Research Activities with Project Assistance in Methodo logy 19 -2 Page SEMINARS AND STUDY TOURS Seminars Organized in Cooperation with Other Institutions 21 Seminars Organized for Visiting Scholars 22 Seminars Organized for ADC Fellows 23 Seminars Attended by the Project Supported Participants 24 Study Tours 24 PUBLICATIONS Seminar Reports 26 Research Paper Series 26 REFLECTION 30 APPENDICES: The following abbreviations are used for various institutions throughout this report: HMG His Majesty's Government of Nepal MFAI Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Irrigation MGA Ministry of Food and Agriculture MOA Ministry of Agriculture PACD Planning and Coordination Division (MOA) EPAD Evaluation and Project Analysis Division (MOA) -

![D Tyf /F]Huf/ Dgqfno J}B]Lzs /F]Huf/ Ljefu](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7105/d-tyf-f-huf-dgqfno-j-b-lzs-f-huf-ljefu-7697105.webp)

D Tyf /F]Huf/ Dgqfno J}B]Lzs /F]Huf/ Ljefu

g]kfn ;/sf/ >d tyf /f]huf/ dGqfno j}b]lzs /f]huf/ ljefu Permission S.No. Number Recruiting Agency Proprietor Name Telephone No RA Address PREMIER HUMAN RESOURCE PVT. LTD. Chitrabhanjyan-7, 1 853 (A.M. OVERSEAS PVT. LTD.) Ganga Datta Rijal 9851106228 Shyangja Anoj Kumar Shrestha 9851075625 Butwal Binod Neupane 9851095894 Bhairahawa Deepak Kharel 9851095817 Bhairahawa 2 554/062/63 A JOURNEYMAN OVERSEAS PVT. LTD. Binod Neupane 9851095894 Bhairahawa Pramod Kumar Ghale Ganardan Uprity Kishor Kumar Chaudhari 3 354/059/60 A One Overseas Pvt. Ltd. Ram Walidas Kathwania Mohan Kumar Rawat tri.na.pa. 4, ghorahi, dang 892/067/06 4 8 A. M. B. Human Resources Pvt. Ltd. Bimal Kumar Rawat 9841405872 tri.na.pa. 4, ghorahi, dang Kamalpokhari, 5 729/06465 A.B. EMPLOYMENT SOLUTIONS PVT. LTD. Desh Bandhu Basnet 9851089118 Kathmandu Those Bazar 6, Kausalya Shrestha 4427427 Ramechhap 6 494/061/62 A.K. Overseas Pvt. Ltd. Amit Bahadur Shresth 4427427 KTM, 2 7 473 A.N.S.ASSOCIATES PVT. LTD. Narendra Raj Sharma 598/062/06 8 3 A.S. INTERNATIONAL PVT. LTD. Sanju Miya 9851098346 Kathmandu, Bagbazar-31 1029/2068/ 9 069 AADARSHA HUMAN RESOURCES PVT.LTD. Shiv Shankar Prasad Singh Milan Thapa 9851046960 Sukhaura 3, Baglung 10 609/062/63 AAKARSHAN INTERNATIONAL PVT. LTD. 10 609/062/63 AAKARSHAN INTERNATIONAL PVT. LTD. Prem Karki 9851030431 Sittalpati 2, Sindhuli 11 142/056/57 Aakash Overseas Company Sewa Pvt. Ltd. Pushpa Raj Neupane 917/067/06 12 8 AAKRITI RECRUITING PVT. LTD Kuncha Dorje Dimdong 9851117304 Bhadrakali-4, Sindhuli Bal Bhadra Dhakal Saha Bahadur Rana 13 227/058/59 AAMIDABA BUDDHA MANPOWER PVT. -

Tribhuvan University in Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE

NEPAL–BRITAIN RELATIONS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO GURKHA SOLDIERS A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Tribhuvan University in Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE Submitted by RAM NARAYAN KANDANGWA Central Department of Political Science Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal March 2008 LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION We, the undersigned, certify that this dissertation entitled, Nepal-Britain Relations with Special Reference to Gurkhas, was prepared by Mr. Ram Narayan Kandangwa under our guidance. We, hereby, recommend this dissertation for final examination by the Research Committee of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tribhuvan University, in fulfilment of the requirement for the DEGREE of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE. Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Prof. Dr. Ram Kumar Dahal Supervisor _______________________________ Prof. Dr. Shyam Kishore Singh Expert _______________________________ Dr. Prem Sharma Expert Date: ___________________ 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research work would in no way have been completed without the invaluable guidance, cooperation and assistance from numerous experts as well as help and inspiration from many people of various walks of life. This researcher would like to express the deepest indebtedness to his most respected and revered supervisor, Prof. Dr. Ram Kumar Dahal, TU, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, who provided extremely important guidance and suggestions ever since I embarked on this work. This work, in the absence of his constructive and perpetual instructions, would have been unthinkable. In similar fashion, this researcher owes enormous gratitude to Prof. Dr. Shyam Kishore Singh, TU, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, who also did not lag behind in giving essential instructions and advice. -

A Ycotrt*^ | Ic^Jt^. /A>|

CF Item = Barcode Top - Note at Bottom = Page 1 CF_ltem_One_BC5-Top-Sign Date 15-Nov-2002 Time 7:18:40 PM Login ask CF/RAI/USAA/DB01/HS/2002-00070 Full Item Register Number [auto] CF/RAI/USAA/DB01/HS/2002-00070 ExRef: Document Series/Year/Number Record Item Title The WET History: [Part 1 PDF version to 94] Water and Sanitation in UNICEF 1946-1986 - 01 Dec 1986. This was early version which eventually became the Water and Sanitation Monograph. Date Created / on Item Date Registered Date Closed/Superceeded 15-Nov-2002 15-Nov-2002 Primary Contact Martin Beyer Owner Location Records & Archive Management Unit =80669443 Home Location History Related Records =60909132 Current Location Records & Archive Management Unit =80669443 Fd1: Type: IN, OUT, INTERNAL? Fd2: Lang ?Sender Refor Cross Rel F3: Format Container Record Container Record (Title) N1: Numb of pages A/2: Doc Year N3: Doc Number 0 0 0 Full GCG Code Plan Number Record GCG File Plan Da 1:Date Published Da2:Date Received Date3 Priority Record Type A02a Item Hist Corr - CF/RAI/USAA/DB01/HS DOS File Name Electronic Details No Document Alt Bar code = RAMP-TRIM Record Number CF/RAI/USAA/DB01/HS/2002-00070 Notes Print Name of Person Submit Images Signature Of Person Submit Number of images without cover A yCoTrt*^ | ic^jt^. /a>| UNICEF DB Name cframpOl o^T-ift.*.* <ft6l-9\6\ m-;jw •*&«g AUOXSIH &• ia/n ift; -M 0 r* ^ : 9H«L i «H >v^'>-) w • i>**va j-»v-w^ ^ * I C ^ THE WET HISTORY WATER SUPPLY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SANITATION IN UNICEF 1946 - 1986 by Martin G.'Beyer UNICEF WET Monographs No. -

S.No. Name Old Pp No

S.NO. NAME OLD PP NO. P1 NAR BAHADUR THAPA, SYANGJA 2003600 P2 NARENDRA KUMAR KAMBANG, PANCHTHAR 5326301 P3 KAMAL KUMAR KARKI, DHANKUTA 1922923 P4 KAMI NURPU TAMANG, NUWAKOT 2031928 P5 CHANDRA BAHADUR TAMANG, MORANG 2089734 P6 BAL KRISHNA GHIMIRE, JHAPA 5334032 P7 RATNA BAHADUR SHRESTHA, SINDHUPALCHOK 2350890 P8 RAJENDRA PRASAD RIJAL, BHAKTAPUR 2511800 P9 CHANDRA BAHADUR GURUNG, NAWALPARASI 5333678 P10 KHIR BAHADUR KARKI, DHANKUTA 5333734 P11 KAUSHAL KUMAR DAS, SAPTARI 5325189 P12 KAMAL BHANDARI, RUKUM 4343678 P13 KAMAL PRASAD GHIMIRE, PANCHTHAR 1943823 P14 KESHAB BAHADUR MAJHI, MAKAWANPUR 5332010 P15 KRISHNA BAHADUR BIST, DADELDHURA 5322764 P16 KUL BAHADUR MAGAR, MORANG 5331770 P17 BISHNU BAHADUR SOMAI, PALPA 3081721 P18 CHHABILA KHATWE, SAPTARI 2073821 P19 CHITRA SING BISHWOKARMA, TANAHUN 1870473 P20 BHIM BAHADUR RAI, NAWALPARASI 2172957 P21 DAL BAHADUR GURUNG, SYANGJA 2560734 P22 RAMESH BISUNKHE, KATHMANDU 3279933 P23 MOHAN OJHA, TAPLEJUNG 2473546 P24 BED NIDHI BHANDARI, ILAM 3313107 P25 TIL BAHADUR SARU, PALPA 5334026 P26 BIR BAHADUR RAI, OKHALDHUNGA 4078036 P27 SANKAR RAJBANSHI, JHAPA 5268976 P28 NEB BAHADUR KAMI, DANG 5198116 P29 BISHNU RANA, KANCHANPUR 4074891 P30 CHANDRA PRAKASH BUDHAMAGAR, ROLPA 5290850 P31 SUMAN LIMBU, TAPLEJUNG 4719172 P32 RUPSEN SAH, RAUTAHAT 2365558 P33 KISAN BISHWAKARMA, KASKI 2531481 P34 ARJUN GURUNG, KASKI 2709420 P35 BAHALI RANA, KANCHANPUR 3900581 P36 MO HAKIM, MORANG 4729639 P37 NARAYAN SING SARU, PALPA 5309460 P38 HASTA BAHADUR ROKA, GORKHA 5334044 P39 MAN BAHADUR TAMANG, OKHALDHUNGA 5333976 P40 ARUN -

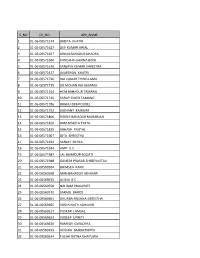

S No Dl No App Name 1 01-06-00571574 Babita Khatri 2 01-06-00571627 Dev Kumar Awal 3 01-06-00571657 Arjun Bahadur Khadka 4 01-0

S_NO DL_NO APP_NAME 1 01-06-00571574 BABITA KHATRI 2 01-06-00571627 DEV KUMAR AWAL 3 01-06-00571657 ARJUN BAHADUR KHADKA 4 01-06-00571660 KANCHHA GHAWA BADE 5 01-06-00571676 SANJAYA KUMAR SHRESTHA 6 01-06-00571677 AKARSHAN KHATRI 7 01-06-00571726 RAJ KUMAR THING LAMA 8 01-06-00571735 DR.MOHAN RAJ SHARMA 9 01-06-00571744 HEM BAHADUR TAMANG 10 01-06-00571746 SARUP SINGH TAMANG 11 01-06-00571786 RAGHU DEB POUDEL 12 01-06-00571792 SUSHANT RAJAURA 13 01-06-00571806 RIDDHI BAHADUR MAHARJAN 14 01-06-00571810 RAM BHAKTA TYATA 15 01-06-00571835 ABHASH PHUYAL 16 01-06-00571907 GITA SHRESTHA 17 01-06-00571934 SANJAY DYOLA 18 01-06-00571944 AMIT K.C. 19 01-06-00571987 LAL BAHADUR BOGATI 20 01-06-00571988 GANESH PRASAD SHREEVASTAV 21 01-06-00569504 BHIMSEN KARKI 22 01-06-00569508 MAN BAHADUR ADHIKARI 23 01-06-00569535 ALISSA K.C. 24 01-06-00569558 NAI RAM PRAJAPATI 25 01-06-00569570 SARAJU BAJIKO 26 01-06-00569601 DHURBA KRISHNA SHRESTHA 27 01-06-00569605 SURYA NATH ADHIKARI 28 01-06-00569617 PUSKAR LAMSAL 29 01-06-00569623 SUDEEP UPRETI 30 01-06-00569626 RAMESH GWACHHA 31 01-06-00569633 RUKSHA BAJRACHARYA 32 01-06-00569634 TULSHI RATNA GHATUWA 33 01-06-00569639 JAGADISHWOR KARKI 34 01-06-00569640 HARIRAM BOYAJU 35 01-06-00569663 SUNUP GORKHALI 36 01-06-00569676 PURNA BAHADUR AWAL 37 01-06-00569678 TEJ BAHADUR SHRESTHA 38 01-06-00569683 ARCHANA PRAJAPATI 39 01-06-00569709 CHUDAMANI BASTOLA 40 01-06-00569728 BAL SUNDAR ADUWA 41 01-06-00569731 ISHWOR PRAJAPATI 42 01-06-00569746 JAGESHWOR KARKI 43 01-06-00569749 SHYAM PRAJAPATI 44 01-06-00569752 KESHAB -

S31q Special Evaluation of the Resources

S31Q 63/ SPECIAL EVALUATION OF THE RESOURCES CONSERVATION AND UTILIZATION PROJECT Under Contract No. PDC-1406-I-04-1096-00 Work Order No. 4 Submitted To: USAID/Nepal Prepared By: Frederick F. Simmons, Team Leader DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES, INC. Charlotte Miller Office of International Cooperation and Development U.S. Department of Agriculture Prachanda Pradhan Development Research and Communication Group Kathmandu, Nepal David B. Thorud College of Forest Resources University of Washington April 1983 DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES, INC. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the staff of USAID/Nepal, officials of His Majesty's Government of Nepal, the RCUP and SECID staff, and the people of Mustang, Myagdi and Gorkha for their openness and hospitable assistance and cooperation despite the special burdens such inquisitive visitors bring. Annex 2 contains the names of the many persons who met with the team and patiently answered their questions. DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES, INC. ii LIST OF ACRONYMS ADB/N Agriculture Development Bank, Nepal ADB Asian Development Bank ADO Agriculture Development Officer CCC Catchment Conservation Officer COo Chief District Officer DFO Divisional Forest Officer ISCWM Department of Livestock Development and Animal Husbandry FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FY Fiscal Year GON Government of Nepal GTZ German Technical Cooperation HMG/N His Majesty's Government, Nepal IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction and Development IRNR Institute for Renewable Natural Resources IHOP Integrated Hill Development Project IROP Integrated Rural Development Project JTA Junior Technical Assistant K-BIRD Karnali Bheri Integrated Rural Development Project KHARDP Koshi Hill Area Rural Development Project NCCNR National Council for the Conservation of Natural Resources PCC Panchayat Conservation Committee PIC Project Implementation Committee PRDP Panchayat Resource Development Plans RCUP Resource Conservation and Utilization Project DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES, INC.