Download/En/ (Accessed 8 Sept 2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pioneering E-Sport: the Experience Economy and the Marketing of Early 1980S Arcade Gaming Contests

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 2254-2274 1932–8036/20130005 Pioneering E-Sport: The Experience Economy and the Marketing of Early 1980s Arcade Gaming Contests MICHAEL BOROWY DAL YONG JIN Simon Fraser University This article sets out to historicize the development of e-sport (organized competitive digital gaming) in the early 1980s using three new conceptual frameworks. We identify e-sport as an accompaniment of the broader embryonic gamer culture, a hallmark of the “experience economy” concept, and as a succession of consumer practices whose development was coterminous with the rise of event marketing as a leading promotional business strategy. By examining the origins of e-sport as both a marketized event and experiential commodity, we see this period as a transitory era bridging different phases in the areas of sports, marketing, and technology, resulting in the expansion of competitive cyberathleticism. Keywords: e-sport, professional gamer, arcade, experience economy, event marketing, video games, public events Introduction In the early 2000s, competitive player-versus-player digital game play (henceforth e-sports) has been a heavily promoted feature of overall gamer culture. Although e-sport—known as an electronic sport and the leagues in which players compete through networked games and related activities (Jin, 2010)— has existed since the early 1980s, the increased attention toward the activity in the 21st century has signaled that the gaming industry is adopting more flexible avenues of public event consumption with the goal of generating higher profit margins. While stand-alone e-sports events are common, their use as adjuncts of other industry events, including major trade shows, press conferences, and even traveling orchestras, demonstrates that competitive gaming continues to play a major role in the machinery of game industry event marketing. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Sega Megadrive European PAL Checklist

The Sega Megadrive European PAL Checklist □ 688 Attack Sub □ Crack Down □ Gunship □ Aaahh!!! Real Monsters □ Crue Ball □ Gunstar Heroes □ Addams Family Values □ Cutthroat Island □ Gynoug □ Addams Family, The □ Cyberball □ Hard Drivin' □ Adventures of Batman & Robin, The □ Cyborg Justice □ Hardball (Box) □ Adventures of Mighty Max, The □ Daffy Duck in Hollywood □ Hardball III □ Aero the Acro-Bat □ Dark Castle □ Hardball '94 □ Aero the Acro-Bat 2 □ David Robinson's Supreme Court □ Haunting, The □ After Burner 2 □ Davis Cup World Tour □ Havoc □ Aladdin □ Death and Return of Superman, The □ Hellfire □ Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle □ Decap Attack □ Herzog Zwei □ Alien 3 □ Demolition Man □ Home Alone □ Alien Soldier □ Desert Demolition starring Road Runner □ Hook □ Alien Storm □ Desert Strike: Return to the Gulf □ Hurricanes □ Alisia Dragoon □ Dick Tracy □ Hyperdunk □ Altered Beast □ Dino Dini's Soccer □ Immortal, The □ Andre Agassi Tennis □ Disney Collection, The □ Incredible Crash Dummies, The □ Animaniacs □ DJ Boy □ Incredible Hulk, The □ Another World □ Donald in Maui Mallard □ Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade □ Aquatic Games starring James Pond □ Double Clutch □ International Rugby □ Arcade Classics □ Double Dragon (Box) □ International Sensible Soccer □ Arch Rivals □ Double Dragon 3: The Arcade Game □ International Superstar Soccer Deluxe □ Ariel: The Little Mermaid □ Double Hits: Micro Machines & Psycho Pinball □ International Tour Tennis □ Arnold Palmer Tournament Golf □ Dr. Robotnik's Mean Bean Machine □ Izzy's Quest for the -

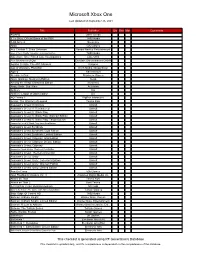

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Brace Yourself for Lightspeed Arcade Multiplayer Mayhem in Laser League

BRACE YOURSELF FOR LIGHTSPEED ARCADE MULTIPLAYER MAYHEM IN LASER LEAGUE 505 Games and Roll7 Team Up to Redefine the Arcade Genre with Fast-Paced, Exhilarating Online Competition for Everyone CALABASAS, Calif. – June 9, 2017 – 505 Games announced today a partnership with BAFTA- winning indie dev magicians Roll7 on Laser League , a fast, fun, multiplayer arcade-style action game. Known for the award-winning OlliOlli series and NOT A HERO , Roll7 bring their trademark addictive gameplay to an original vision of near-future competition. With up to 4 v. 4 intense online or local multiplayer mode with friends, Laser League ’s frenetic yet intuitive matches are easy to play but difficult to master, in a throwback to the heyday of gaming’s more approachable arcade action. Witness the exhilarating action in the first trailer. [INSERT ESRB or PEGI embed code ] “We have admired and enjoyed Roll7’s work from afar ever since the first OlliOlli game,” said Tim Woodley, senior vice president of brand and marketing, 505 Games. “When we saw the first prototype for Laser League , we could already feel that all-too-rare ‘just one more go’ impulse. We jumped at the chance to help Roll7 take their proven studio to the next level and realize their ambitions for Laser League. ” In Laser League , the exhilarating, high-octane contact sport of 2150, players battle against the opposition for control of nodes that bathe the arena in deadly light. Evading rival colored beams, teams attempt to fry their opponents with speed, strength and strategy. Special offensive and defensive abilities, as well as game-changing power-ups on the arena floor, provide an edge at the crucial moment. -

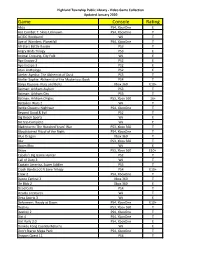

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Course Organization CISC 877 Video Game Development Week 1: Introduction

Course Organization CISC 877 Video Game Development Week 1: Introduction T.C. Nicholas Graham [email protected] http://equis.cs.queensu.ca/wiki/index.php/CISC_877 Winter term, 2010 equis: engineering interactive systems Topics include… Timeline and Marking Scheme Video game design Gaminggp platforms and fundamental technolo gies Activity Due Date Grade January 26, Game development processes and pipeline Project Proposal (2-3 pages, hand-in) 10% 2010 Software architecture of video games Progress Presentation (involves Mar 2, 2010 20% Video games as distributed systems presentation and online report) Game physics Informal progress reports Weekly 5% GAIGame AI April 6, 2010 Scripting languages Final Project Presentation / Show 10% (tentative) Game development tools Final Project Report April 9, 2010 45% Social and ethical aspects of video games Class Participation 10% User in terf aces of gam es equis: engineering interactive systems equis: engineering interactive systems Homework Project proposal (for next week) Wiki contains detailed description of project ideas, game you will be extending The Project Proposal to be posted on Wiki – create yourself an account Form your own project groups – pick project appropriate to group size OGRE tutorials (over next two weeks) …see Wiki for details Download URL: http://equis.cs.queensu.ca/~graham/cisc877/soft/ equis: engineering interactive systems equis: engineering interactive systems The Game: Life is a Village The Game: Life is a Village Goal is to build an interesting village -

Fibre Reinforced Plastic Concepts for Structural Chassis Parts

Transport Research Arena 2014, Paris Fibre Reinforced Plastic Concepts for Structural Chassis Parts Oliver Deisser*, Prof. Dr. Horst E. Friedrich, Gundolf Kopp German Aerospace Center / Institute of Vehicle Concepts Pfaffenwaldring 38-40, 70569 Stuttgart Abstract Fibre reinforced plastics (FRP) have a high potential for reducing masses of automotive parts, but are seldom used for structural parts in the chassis. If the whole chassis concept is adapted to the new material, then a high weight saving potential can be gained and new body concepts can result. DLR Institute of Vehicle Concepts designed and dimensioned a highly stressed structural part in FRP. A topology optimisation of a defined working space with the estimated loads was performed. The results were analysed and fibre reinforced part concepts derived, detailed and evaluated. Especially by the use of the new FRP material system in the chassis area, a weight saving of more than 30% compared to the steel reference was realised. With the help of those concepts it is shown, that there is also a great weight saving potential in the field of chassis design, if the design fits with the material properties. The existing concepts still have to be detailed further, simulated and validated to gain the full lightweight potential. Keywords: Fibre Reinforced Plastics; Chassis Design; Lightweight Design Concepts; Finite Element Simulation; FEM. Résumé Plastiques renforcés de fibres (PRF) ont un fort potentiel de réduction des masses de pièces automobiles, mais sont rarement utilisés pour des pièces de structure du châssis. Si le concept de châssis est adapté au nouveau matériel, un potentiel élevé d'épargne de poids peut être acquis et de nouveaux concepts de construction peuvent en résulter. -

Michelin to Make Playstation's Gran

PRESS INFORMATION NEW YORK, Aug. 23, 2019 — PlayStation has selected Michelin as “official tire technology partner” for its Gran Turismo franchise, the best and most authentic driving game, the companies announced today at the PlayStation Theater on Broadway. Under the multi-year agreement, Michelin also becomes “official tire supplier” of FIA Certified Gran Turismo Championships, with Michelin-branded tires featured in the game during its third World Tour live event also in progress at PlayStation Theater throughout the weekend. The relationship begins by increasing Michelin’s visibility through free downloadable content on Gran Turismo Sport available to users by October 2019. The Michelin-themed download will feature for the first time: . A new Michelin section on the Gran Turismo Sport “Brand Central” virtual museum, which introduces players to Michelin’s deep history in global motorsports, performance and innovation. Tire technology by Michelin available in the “Tuning” section of Gran Turismo Sport, applicable to the game’s established hard, medium and soft formats. On-track branding elements and scenography from many of the world’s most celebrated motorsports competitions and venues. In 1895, the Michelin brothers entered a purpose-built car in the Paris-Bordeaux-Paris motor race to prove the performance of air-filled tires. Since that storied race, Michelin has achieved a record of innovation and ultra-high performance in the most demanding and celebrated racing competitions around the world, including 22 consecutive overall wins at the iconic 24 Hours of Le Mans and more than 330 FIA World Rally Championship victories. Through racing series such as FIA World Endurance Championship, FIA World Rally Championship, FIA Formula E and International Motor Sports Association series in the U.S., Michelin uses motorsports as a laboratory to collect vast amounts of real-world data that power its industry-leading models and simulators for tire development. -

Arcade-Style Game Design: Postwar Pinball and The

ARCADE-STYLE GAME DESIGN: POSTWAR PINBALL AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF COIN-OP VIDEOGAMES A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Christopher Lee DeLeon In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Digital Media in the School of Literature, Communication and Culture Georgia Institute of Technology May 2012 ARCADE-STYLE GAME DESIGN: POSTWAR PINBALL AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF COIN-OP VIDEOGAMES Approved by: Dr. Ian Bogost, Advisor Dr. John Sharp School of LCC School of LCC Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Brian Magerko Steve Swink School of LCC Creative Director Georgia Institute of Technology Enemy Airship Dr. Celia Pearce School of LCC Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: March 27, 2012 In memory of Eric Gary Frazer, 1984–2001. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank: Danyell Brookbank, for companionship and patience in our transition to Atlanta. Ian Bogost, John Sharp, Brian Magerko, Celia Pearce, and Steve Swink for ongoing advice, feedback, and support as members of my thesis committee. Andrew Quitmeyer, for immediately encouraging my budding pinball obsession. Michael Nitsche and Patrick Coursey, for also getting high scores on Arnie. Steve Riesenberger, Michael Licht, and Tim Ford for encouragement at EALA. Curt Bererton, Mathilde Pignol, Dave Hershberger, and Josh Wagner for support and patience at ZipZapPlay. John Nesky, for his assistance, talent, and inspiration over the years. Lou Fasulo, for his encouragement and friendship at Sonic Boom and Z2Live. Michael Lewis, Harmon Pollock, and Tina Ziemek for help at Stupid Fun Club. Steven L. Kent, for writing the pinball chapter in his book that inspired this thesis. -

Artificial Intelligence in Racing Games

BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science ABDAL MOHAMED BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Sections 1. History of AI in Racing Games 2. Neural Networks in Games BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science History Gran Trak 10 Single-player racing arcade game released by Atari in 1974 Did not have any AI Pole Position Single- player racing game released by Namco in 1982 Considered first racing game with AI BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science History Super Mario Kart Addition of Power Ups Released in 1992 for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Driver Free- form World 1998 video game developed by Reflections Interactive Vehicular Combat: Power Ups + Free Form World BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Simple Areas of AI in Racing Games 1. Steering Sort of Basic Used in Formula One-Built to win, GTA3 2001 for background animation purpose. 2. Pathfinding Becomes more free-form world Would need to make decision on where to go. Need to find the best path between two points, avoiding any obstacles. BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Steering + Racing Lines Racing Lines methods was used extensively until there was CPU power to do something else. It is just a drawn line in which the cars follow that line or stuck to that line. It uses Spline, where addition information such as velocity is included. Advantage It is very easy to create cheap spine creation tool Disadvantage Very limited- and gets very difficult Not very realistic- as car follows line, no response to deflection BSc in Artificial Intelligence and Computer Science Pathfinding + Tactical AI Racing line does not really work with free-form world so one of the solutions is having set path to where the car/ character is fleeing. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51.