Arxiv:2009.00701V1 [Eess.SY] 1 Sep 2020 the first Proposed Analogy Related Force to Voltage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 6 Two-Port Network Model

Chapter 6 Two-Port Network Model 6.1 Introduction In this chapter a two-port network model of an actuator will be briefly described. In Chapter 5, it was shown that an automated test setup using an active system can re- create various load impedances over a limited range of frequencies. This test set-up can therefore be used to automatically reproduce any load impedance condition (related to a possible application) and apply it to a test or sample actuator. It is then possible to collect characteristic data from the test actuator such as force, velocity, current and voltage. Those characteristics can then be used to help to determine whether the tested actuator is appropriate or not for the case simulated. However versatile and easy to use this test set-up may be, because of its limitations, there is some characteristic data it will not be able to provide. For this reason and the fact that it can save a lot of measurements, having a good linear actuator model can be of great use. Developed for transduction theory [29], the linear model presented in this chapter is 77 called a Two-Port Network model. The automated test set-up remains an essential complement for this model, as it will allow the development and verification of accuracy. This chapter will focus on the two-port network model of the 1_3 tube array actuator provided by MSI (Cf: Figure 5.5). 6.2 Theory of the Two–Port Network Model As a transducer converts energy from electrical to mechanical forms, and vice- versa, it can be modelled as a Two-Port Network that relates the electrical properties at one port to the mechanical properties at the other port. -

Analysis of Microwave Networks

! a b L • ! t • h ! 9/ a 9 ! a b • í { # $ C& $'' • L C& $') # * • L 9/ a 9 + ! a b • C& $' D * $' ! # * Open ended microstrip line V + , I + S Transmission line or waveguide V − , I − Port 1 Port Substrate Ground (a) (b) 9/ a 9 - ! a b • L b • Ç • ! +* C& $' C& $' C& $ ' # +* & 9/ a 9 ! a b • C& $' ! +* $' ù* # $ ' ò* # 9/ a 9 1 ! a b • C ) • L # ) # 9/ a 9 2 ! a b • { # b 9/ a 9 3 ! a b a w • L # 4!./57 #) 8 + 8 9/ a 9 9 ! a b • C& $' ! * $' # 9/ a 9 : ! a b • b L+) . 8 5 # • Ç + V = A V + BI V 1 2 2 V 1 1 I 2 = 0 V 2 = 0 V 2 I 1 = CV 2 + DI 2 I 2 9/ a 9 ; ! a b • !./5 $' C& $' { $' { $ ' [ 9/ a 9 ! a b • { • { 9/ a 9 + ! a b • [ 9/ a 9 - ! a b • C ) • #{ • L ) 9/ a 9 ! a b • í !./5 # 9/ a 9 1 ! a b • C& { +* 9/ a 9 2 ! a b • I • L 9/ a 9 3 ! a b # $ • t # ? • 5 @ 9a ? • L • ! # ) 9/ a 9 9 ! a b • { # ) 8 -

Brief Study of Two Port Network and Its Parameters

© 2014 IJIRT | Volume 1 Issue 6 | ISSN : 2349-6002 Brief study of two port network and its parameters Rishabh Verma, Satya Prakash, Sneha Nivedita Abstract- this paper proposes the study of the various ports (of a two port network. in this case) types of parameters of two port network and different respectively. type of interconnections of two port networks. This The Z-parameter matrix for the two-port network is paper explains the parameters that are Z-, Y-, T-, T’-, probably the most common. In this case the h- and g-parameters and different types of relationship between the port currents, port voltages interconnections of two port networks. We will also discuss about their applications. and the Z-parameter matrix is given by: Index Terms- two port network, parameters, interconnections. where I. INTRODUCTION A two-port network (a kind of four-terminal network or quadripole) is an electrical network (circuit) or device with two pairs of terminals to connect to external circuits. Two For the general case of an N-port network, terminals constitute a port if the currents applied to them satisfy the essential requirement known as the port condition: the electric current entering one terminal must equal the current emerging from the The input impedance of a two-port network is given other terminal on the same port. The ports constitute by: interfaces where the network connects to other networks, the points where signals are applied or outputs are taken. In a two-port network, often port 1 where ZL is the impedance of the load connected to is considered the input port and port 2 is considered port two. -

Introduction to Transmission Lines

INTRODUCTION TO TRANSMISSION LINES DR. FARID FARAHMAND FALL 2012 http://www.empowermentresources.com/stop_cointelpro/electromagnetic_warfare.htm RF Design ¨ In RF circuits RF energy has to be transported ¤ Transmission lines ¤ Connectors ¨ As we transport energy energy gets lost ¤ Resistance of the wire à lossy cable ¤ Radiation (the energy radiates out of the wire à the wire is acting as an antenna We look at transmission lines and their characteristics Transmission Lines A transmission line connects a generator to a load – a two port network Transmission lines include (physical construction): • Two parallel wires • Coaxial cable • Microstrip line • Optical fiber • Waveguide (very high frequencies, very low loss, expensive) • etc. Types of Transmission Modes TEM (Transverse Electromagnetic): Electric and magnetic fields are orthogonal to one another, and both are orthogonal to direction of propagation Example of TEM Mode Electric Field E is radial Magnetic Field H is azimuthal Propagation is into the page Examples of Connectors Connectors include (physical construction): BNC UHF Type N Etc. Connectors and TLs must match! Transmission Line Effects Delayed by l/c At t = 0, and for f = 1 kHz , if: (1) l = 5 cm: (2) But if l = 20 km: Properties of Materials (constructive parameters) Remember: Homogenous medium is medium with constant properties ¨ Electric Permittivity ε (F/m) ¤ The higher it is, less E is induced, lower polarization ¤ For air: 8.85xE-12 F/m; ε = εo * εr ¨ Magnetic Permeability µ (H/m) Relative permittivity and permeability -

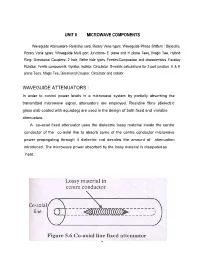

WAVEGUIDE ATTENUATORS : in Order to Control Power Levels in a Microwave System by Partially Absorbing the Transmitted Microwave Signal, Attenuators Are Employed

UNIT II MICROWAVE COMPONENTS Waveguide Attenuators- Resistive card, Rotary Vane types. Waveguide Phase Shifters : Dielectric, Rotary Vane types. Waveguide Multi port Junctions- E plane and H plane Tees, Magic Tee, Hybrid Ring. Directional Couplers- 2 hole, Bethe hole types. Ferrites-Composition and characteristics, Faraday Rotation. Ferrite components: Gyrator, Isolator, Circulator. S-matrix calculations for 2 port junction, E & H plane Tees, Magic Tee, Directional Coupler, Circulator and Isolator WAVEGUIDE ATTENUATORS : In order to control power levels in a microwave system by partially absorbing the transmitted microwave signal, attenuators are employed. Resistive films (dielectric glass slab coated with aquadag) are used in the design of both fixed and variable attenuators. A co-axial fixed attenuator uses the dielectric lossy material inside the centre conductor of the co-axial line to absorb some of the centre conductor microwave power propagating through it dielectric rod decides the amount of attenuation introduced. The microwave power absorbed by the lossy material is dissipated as heat. 1 In waveguides, the dielectric slab coated with aquadag is placed at the centre of the waveguide parallel to the maximum E-field for dominant TEIO mode. Induced current on the lossy material due to incoming microwave signal, results in power dissipation, leading to attenuation of the signal. The dielectric slab is tapered at both ends upto a length of more than half wavelength to reduce reflections as shown in figure 5.7. The dielectric slab may be made movable along the breadth of the waveguide by supporting it with two dielectric rods separated by an odd multiple of quarter guide wavelength and perpendicular to electric field. -

A Unified State-Space Approach to Rlct Two-Port

A UNIFIED STATE-SPACE APPROACH TO RLCT TWO-PORT TRANSFER FUNCTION SYNTHESIS By EDDIE RANDOLPH FOWLER Bachelor of Science Kan,sas State University Manhattan, Kansas 1957 Master of Science Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas 1965 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Col.lege of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1969 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SEP 2l1 l969 ~ A UNIFIED STATE-SPACE APPROACH TO RLCT TWO-PORT TRANSFER FUNCTION SYNTHESIS Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii AC!!..NOWLEDGEMENTS Only those that have had children in school all during their graduate studies know the effort and sacrifice that my wife, Pat, has endured during my graduate career. I appreciate her accepting this role without complainL Also I am deeply grateful that she was willing to take on the horrendous task of typing this thesis. My heartfelt thanks to Dr. Rao Yarlagadda, my thesis advisor, who was always available for $Uidance and help during the research and writing of this thesis. I appreciate the assistance and encouragement of the other members of my graduate comruitteei, Dr. Kenneth A. McCollom, Dr. Charles M. Bacon ar1d Dr~ K.ar 1 N.... ·Re id., I acknowledge Paul Howell, a fellow Electrical Engineering grad uate student, whose Christian Stewardship has eased the burden during these last months of thesis preparation~ Also Dwayne Wilson, Adminis trative Assistant, has n1y gratitude for assisting with the financial and personal problems of the Electrical Engineering graduate students. My thanks to Dr. Arthur M. Breipohl for making available the assistant ship that was necessary before it was financially possible to initiate my doctoral studies. -

The Stripline Circulator Theory and Practice

The Stripline Circulator Theory and Practice By J. HELSZAJN The Stripline Circulator The Stripline Circulator Theory and Practice By J. HELSZAJN Copyright # 2008 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http:// www.wiley.com/go/permission. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. -

Transmission Line and Lumped Element Quadrature Couplers

High Frequency Design From November 2009 High Frequency Electronics Copyright © 2009 Summit Technical Media, LLC QUADRATURE COUPLERS Transmission Line and Lumped Element Quadrature Couplers By Gary Breed Editorial Director uadrature cou- This month’s tutorial article plers are used for reviews the basic design Qpower division and operation of power and combining in circuits divider/combiners with where the 90º phase shift ports that have a 90- between the two coupled degree phase difference ports will result in a desirable performance characteristic. Common uses of quadrature couplers include: Antenna feed systems—The combination of power division/combining and 90º phase shift can simplify the feed network of phased array antenna systems, compared to alternative net- Figure 1 · The branch line quadrature works using delay lines, other types of com- hybrid, implemented using λ/4 transmission biners and impedance matching networks. It line sections. is especially useful for feeding circularly polarized arrays. Test and measurement systems—The phase each module has active devices in push-pull shift performance performance may be suffi- (180º combined), both even- and odd-order ciently accurate for phase comparisons over a harmonics can be reduced, which simplifies substantial fraction of an octave. A less critical output filtering. use is to resolve phase ambiguity in test cir- In an earlier tutorial [1], I introduced a cuits. A number of measurement techniques range of 90º coupler types without much anal- have a discontinuity at 180º—as this value is ysis. In this article, we focus on the two main approached, a 90º phase “rotation” moves the coupler types—the branch-line and coupled- system away from that point. -

Doppler-Based Acoustic Gyrator

applied sciences Article Doppler-Based Acoustic Gyrator Farzad Zangeneh-Nejad and Romain Fleury * ID Laboratory of Wave Engineering, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland; farzad.zangenehnejad@epfl.ch * Correspondence: romain.fleury@epfl.ch; Tel.: +41-412-1693-5688 Received: 30 May 2018; Accepted: 2 July 2018; Published: 3 July 2018 Abstract: Non-reciprocal phase shifters have been attracting a great deal of attention due to their important applications in filtering, isolation, modulation, and mode locking. Here, we demonstrate a non-reciprocal acoustic phase shifter using a simple acoustic waveguide. We show, both analytically and numerically, that when the fluid within the waveguide is biased by a time-independent velocity, the sound waves travelling in forward and backward directions experience different amounts of phase shifts. We further show that the differential phase shift between the forward and backward waves can be conveniently adjusted by changing the imparted bias velocity. Setting the corresponding differential phase shift to 180 degrees, we then realize an acoustic gyrator, which is of paramount importance not only for the network realization of two port components, but also as the building block for the construction of different non-reciprocal devices like isolators and circulators. Keywords: non-reciprocal acoustics; gyrators; phase shifters; Doppler effect 1. Introduction Microwave phase shifters are two-port components that provide an arbitrary and variable transmission phase angle with low insertion loss [1–3]. Since their discovery in the 19th century, such phase shifters have found important applications in devices such as phased array antennas and receivers [4,5], beam forming and steering networks [6,7], measurement and testing systems [8,9], filters [10,11], modulators [12,13], frequency up-convertors [14], power flow controllers [15], interferometers [16], and mode lockers [17]. -

The Dreaded “2-Port Parameters”

The dreaded “2-port parameters” Aims: – To generalise the Thevenin an Norton Theorems to devices with 3 terminals – Develop efficient computational tools to handle feedback connections of non ideal devices L5 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 1 Generalised Thevenin + Norton Theorems • Amplifiers, filters etc have input and output “ports” (pairs of terminals) • By convention: – Port numbering is left to right: left is port 1, right port 2 – Output port is to the right of input port. e.g. output is port 2. – Current is considered positive flowing into the positive terminal of port – The two negative terminals are usually considered connected together • There is both a voltage and a current at each port – We are free to represent each port as a Thevenin or Norton • Since the output depends on the input (and vice-versa!) any Thevenin or Norton sources we use must be dependent sources. • General form of amplifier or filter: I1 I2 Port 1 + Thevenin Thevenin + Port 2 V1 V2 (Input) - or Norton or Norton - (Output) Amplifier L5 Autumn 2009 E2.2 Analogue Electronics Imperial College London – EEE 2 How to construct a 2-port model • Decide the representation (Thevenin or Norton) for each of: – Input port – Output port • Remember the I-V relations for Thevenin and Norton Circuits: – A Thevenin circuit has I as the independent variable and V as the dependent variable: V=VT + I RT – A Norton circuit has V as the independent variable and I as the dependent variable: I = IN + V GN • The source of one port is controlled by the independent variable of the other port. -

The Six-Port Technique with Microwave and Wireless Applications for a Listing of Recent Titles in the Artech House Microwave Library, Turn to the Back of This Book

The Six-Port Technique with Microwave and Wireless Applications For a listing of recent titles in the Artech House Microwave Library, turn to the back of this book. The Six-Port Technique with Microwave and Wireless Applications Fadhel M. Ghannouchi Abbas Mohammadi Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the U.S. Library of Congress. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN-13: 978-1-60807-033-6 Cover design by Yekaterina Ratner © 2009 ARTECH HOUSE 685 Canton Street Norwood, MA 02062 All rights reserved. Printed and bound in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including pho- tocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Artech House cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction to the SixPort Technique 1.1 Microwave Network Theory ........................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Power and Reflection ............................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Scattering Parameters ............................................................................... 3 1.2 Microwave Circuits Design Technologies ...................................................... 6 1.2.1 Microwave Transmission Lines ............................................................... 6 1.2.2 Microwave Passive Circuits .................................................................... -

Modeling & Simulation 2019 Lecture 8. Bond Graphs

Modeling & Simulation 2019 Lecture 8. Bond graphs Claudio Altafini Automatic Control, ISY Linköping University, Sweden 1 / 45 Summary of lecture 7 • General modeling principles • Physical modeling: dimension, dimensionless quantities, scaling • Models from physical laws across different domains • Analogies among physical domains 2 / 45 Lecture 8. Bond graphs Summary of today • Analogies among physical domains • Bond graphs • Causality In the book: Chapter 5 & 6 3 / 45 Basic physics laws: a survey Electrical circuits Hydraulics Mechanics – translational Thermal systems Mechanics – rotational 4 / 45 Electrical circuits Basic quantities: • Current i(t) (ampere) • Voltage u(t) (volt) • Power P (t) = u(t) · i(t) 5 / 45 Electrical circuits Basic laws relating i(t) and u(t) • inductance d 1 Z t L i(t) = u(t) () i(t) = u(s)ds dt L 0 • capacitance d 1 Z t C u(t) = i(t) () u(t) = i(s)ds dt C 0 • resistance (linear case) u(t) = Ri(t) 6 / 45 Electrical circuits Energy storage laws for i(t) and u(t) • electromagnetic energy 1 T (t) = Li2(t) 2 • electric field energy 1 T (t) = Cu2(t) 2 • energy loss in a resistance Z t Z t Z t 1 Z t T (t) = P (s)ds = u(s)i(s)ds = R i2(s)ds = u2(s)ds 0 0 0 R 0 7 / 45 Electrical circuits Interconnection laws for i(t) and u(t) • Kirchhoff law for voltages On a loop: ( X +1; σk aligned with loop direction σkuk(t) = 0; σk = −1; σ against loop direction k k • Kirchhoff law for currents On a node: ( X +1; σk inward σkik(t) = 0; σk = −1; σ outward k k 8 / 45 Electrical circuits Transformations laws for u(t) and i(t) • transformer u1 = ru2 1 i = i 1 r 2 u1i1 = u2i2 ) no power loss • gyrator u1 = ri2 1 i = u 1 r 2 u1i1 = u2i2 ) no power loss 9 / 45 Electrical circuits Example State space model: d 1 i = (u − Ri − u ) dt L s C d 1 u = i dt C C 10 / 45 Mechanical – translational Basic quantities: • Velocity v(t) (meters per second) • Force F (t) (newton) • Power P (t) = F (t) · v(t) 11 / 45 Mechanical – translational Basic laws relating F (t) and v(t) • Newton second law d 1 Z t m v(t) = F (t) () v(t) = F (s)ds dt m 0 • Hook’s law (elastic bodies, e.g.