Food and Power: Addressing Monopolization in America’S Food System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sysco Cheese Product Catalog

> the Sysco Cheese Product Catalog Sysco_Cheese_Cat.indd 1 7/27/12 10:55 AM 5 what’s inside! 4 More Cheese, Please! Sysco Cheese Brands 6 Cheese Trends and Facts Creamy and delicious, 8 Building Blocks... cheese fi ts in with meal of Natural Cheese segments during any Blocks and Shreds time of day – breakfast, Smoked Bacon & Cheddar Twice- Baked Potatoes brunch, lunch, hors d’oeuvres, dinner and 10 Natural Cheese from dessert. From a simple Mild to Sharp Cheddar, Monterey Jack garnish to the basis of and Swiss a rich sauce, cheese is an essential ingredient 9 10 12 A Guide to Great Italian Cheeses Soft, Semi-Soft and for many food service Hard Italian Cheeses operations. 14 Mozzarella... The Quintessential Italian Cheese Slices, shreds, loaves Harvest Vegetable French and wheels… with Bread Pizza such a multitude of 16 Cream Cheese Dreams culinary applications, 15 16 Flavors, Forms and Sizes the wide selection Blueberry Stuff ed French Toast of cheeses at Sysco 20 The Number One Cheese will provide endless on Burgers opportunities for Process Cheese Slices and Loaves menu innovation Stuff ed Burgers and increased 24 Hispanic-Style Cheeses perceived value. Queso Seguro, Special Melt and 20 Nacho Blend Easy Cheese Dip 25 What is Speciality Cheese? Brie, Muenster, Havarti and Fontina Baked Brie with Pecans 28 Firm/Hard Speciality Cheese Gruyère and Gouda 28 Gourmet White Mac & Cheese 30 Fresh and Blue Cheeses Feta, Goat Cheese, Blue Cheese and Gorgonzola Portofi no Salad with 2 Thyme Vinaigrette Sysco_Cheese_Cat.indd 2 7/27/12 10:56 AM welcome. -

Mondelez International Announces $50 Million Investment Opportunity for UK Coffee Site

November 7, 2014 Mondelez International Announces $50 Million Investment Opportunity for UK Coffee Site - Proposal coincides with Banbury coffee plant's 50th anniversary - Planned investment highlights success of Tassimo single-serve beverage system - Part of a multi-year, $1.5 billion investment in European manufacturing BANBURY, England, Nov. 7, 2014 /PRNewswire/ -- Mondelez International, the world's pre-eminent maker of chocolate, biscuits, gum and candy as well as the second largest player in the global coffee market, today announced plans to invest $50 million (£30 million) in its Banbury, UK factory to build two new lines that will manufacture Tassimo beverage capsules. Tassimo is Europe's fastest growing single-serve system, brewing a wide variety of beverages including Jacobs and Costa coffees and Cadbury hot chocolate. The decision is part of Mondelez International's multi-year investment in European manufacturing, under which $1.5 billion has been invested since 2010. The planned investment will create close to 80 roles and coincides with the 50th anniversary of the Banbury factory, which produces coffee brands such as Kenco, Carte Noire and Maxwell House. The Tassimo capsules produced in Banbury will be exported to Western European coffee markets in France and Spain as well as distributed in the UK. "Tassimo is a key driver of growth for our European coffee business, so this $50 million opportunity is a great one for Banbury," said Phil Hodges, Senior Vice President, Integrated Supply Chain, Mondelez Europe. "Over the past 18 months, we've made similar investments in Bournville and Sheffield, underscoring our commitment to UK manufacturing. -

Kraf Tunion Network 02102011

Kraft Union Network October 2, 2011 There’s always something going on at Kraft Foods… Kraft to split itself in two We believe scale will be an increasing source of competitive advantage both in confectionary and in the food industry at large. Irene Rosenfeld, January 2010, Taking our performance to the next level requires a bold new approach: creating two great companies that can optimize value by focusing on their unique drivers of success. Irene Rosenfeld, August 2011 The deals never stop at Kraft foods. On the road to moving from “one of the world’s largest food and beverage companies” to a “global snacks powerhouse”, Kraft in 2007 paid USD 7.2 billion, to acquire Danone’s European biscuit operations, borrowing cash it didn’t have. Kraft steadily raised dividends while closing over 35 factories and eliminating over 20,000 jobs, squeezing out cash through closures, spinoffs and outsourcing, Cost-cutting, layoffs and divestitures fueled more dividend increases and paved the way for even more debt to power the USD 19.5 billion cash-and-share acquisition of UK-based Cadbury in 2010. “Scale”, “supply chain leverage” and marketing “synergies” were the rationale for the Cadbury deal, trotted out in innumerable press releases and conference calls with investors. Synergy and scale yielded to “focus” on August 4 this year, when Kraft announced it would split the corporation into 2 independent publicly traded companies, both headquartered in North America: “A high-growth global snacks business with estimated 2 revenue of approximately $32 billion and a high-margin North American grocery business with estimated revenue of approximately $16 billion. -

Enel Green Power's Renewable Energy Is Part of the History of Mondelēz International's Business Unit in Mexico

Media Relations T (55) 6200 3787 [email protected] enelgreenpower.com ENEL GREEN POWER'S RENEWABLE ENERGY IS PART OF THE HISTORY OF MONDELĒZ INTERNATIONAL'S BUSINESS UNIT IN MEXICO • Enel Green Power supplies up to 77 GWh annually to two Mondelēz International factories with wind energy from its 200 MW Amistad I wind farm located in Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila. • Thanks to this relationship, Mondelēz International has avoided the emission of approximately 33,000 tons of CO2 per year. Mexico City, October 7th, 2020 – Enel Green Power México (EGPM), the renewables subsidiary of Enel Group, joins the celebration of the 8th anniversary of Mondelēz International in the country, by commemorating two years of successful collaboration through an electric power supply contract. Derived from this contract, Mondelēz International has received up to 77 GWh per year of renewable energy to its factories located in the State of Mexico and Puebla. Thanks to the renewable energy supplied by EGPM´s Amistad I wind farm; Mondelēz International has avoided the emission of around 33,000 tons of CO2 per year, equivalent to almost 80% of its emission reduction target for Latin America in 2020. Similarly, this energy is capable of producing approximately more than 100,000 tons annually of product from brands such as Halls, Trident, Bubbaloo, Oreo, Tang and Philadelphia and is enough to light approximately 33,000 Mexican homes for an entire year. “It is an honor for Enel Green Power México to contribute to Mondelēz International environmental objectives and efforts to accelerate energy transition in the country. Today more and more companies are convinced that renewable energies are not only sustainable, but also profitable, which is why this type of agreements serve as a relevant growth path for clean sources in Mexico”, stated Paolo Romanacci, Country Manager of Enel Green Power Mexico. -

Restaurant Trends App

RESTAURANT TRENDS APP For any restaurant, Understanding the competitive landscape of your trade are is key when making location-based real estate and marketing decision. eSite has partnered with Restaurant Trends to develop a quick and easy to use tool, that allows restaurants to analyze how other restaurants in a study trade area of performing. The tool provides users with sales data and other performance indicators. The tool uses Restaurant Trends data which is the only continuous store-level research effort, tracking all major QSR (Quick Service) and FSR (Full Service) restaurant chains. Restaurant Trends has intelligence on over 190,000 stores in over 500 brands in every market in the United States. APP SPECIFICS: • Input: Select a point on the map or input an address, define the trade area in minute or miles (cannot exceed 3 miles or 6 minutes), and the restaurant • Output: List of chains within that category and trade area. List includes chain name, address, annual sales, market index, and national index. Additionally, a map is provided which displays the trade area and location of the chains within the category and trade area PRICE: • Option 1 – Transaction: $300/Report • Option 2 – Subscription: $15,000/License per year with unlimited reporting SAMPLE OUTPUT: CATEGORIES & BRANDS AVAILABLE: Asian Flame Broiler Chicken Wing Zone Asian honeygrow Chicken Wings To Go Asian Pei Wei Chicken Wingstop Asian Teriyaki Madness Chicken Zaxby's Asian Waba Grill Donuts/Bakery Dunkin' Donuts Chicken Big Chic Donuts/Bakery Tim Horton's Chicken -

Case with Questions J Cadbury 1

j Case with questions Cadbury 1 Cadbury is a very well known British confectionery company. Originally a family fi rm started by John Cadbury and grounded in Quaker values and ideals, it started life in 1824 as a shop selling chocolate as a virtuous alternative to alcohol. It went on to become a large-scale manufacturer of chocolate based at the now legendary Bournville factory, built in 1879, and its picturesque workers’ village with its red-brick terraces, cottages, duck ponds and wide open parks. Over the next 100 years Cadbury developed the products that have become so familiar: Dairy Milk in 1905, Milk Tray in 1915, Flake in 1920, Creme Egg in 1923, Roses in 1938 and more. From 1969 it traded as Cadbury Schweppes plc until, in 2008, it separated its global con- fectionery business (which retained the name ‘Cadbury’) from its US beverages business, which was renamed Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc. Cadbury Schweppes had already sold off most of its beverages businesses in other countries around the world, a process started in 1999 and concluded in 2009 with the sale of its Australian beverages business. The reason for the exit from the beverages business was to enable Cadbury to focus more clearly on what it saw as its core strengths in confectionery, and better enhance shareholder value. Beverages had become the ‘poor sister’ in the relationship, with a separate management structure but delivering growth below the targets for the company. In 2008 the newly de-merged Cadbury set as its goal maintaining its market leadership position, and leveraging its scale and advantaged positions so as to maximise growth and returns. -

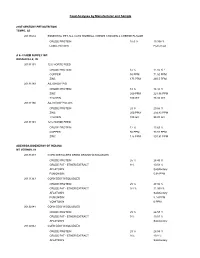

Feed Analyses by Manufacturer and Sample

Feed Analyses by Manufacturer and Sample 21ST CENTURY PET NUTRITION TEMPE, AZ 20133614 ESSENTIAL PET ALL CATS HAIRBALL CHEWS CHICKEN & CHEESE FLAVOR CRUDE PROTEIN 16.6 % 19.398 % LABEL REVIEW Performed A & J FARM SUPPLY INC RUSSIAVILLE, IN 20131101 12% HORSE FEED CRUDE PROTEIN 12 % 11.55 % * COPPER 50 PPM 71.52 PPM ZINC 175 PPM 260.5 PPM 20131189 A&J SHOW PIG CRUDE PROTEIN 18 % 18.34 % ZINC 200 PPM 221.96 PPM TYLOSIN 100 G/T 78.36 G/T 20131190 A&J SHOW PIG 20% CRUDE PROTEIN 20 % 20.66 % ZINC 200 PPM 294.83 PPM TYLOSIN 100 G/T 98.05 G/T 20131191 12% HORSE FEED CRUDE PROTEIN 12 % 13.69 % COPPER 50 PPM 73.88 PPM ZINC 175 PPM 301.81 PPM ABENGOA BIOENERGY OF INDIANA MT VERNON, IN 20131349 CORN DISTILLERS DRIED GRAINS W/SOLUBLES CRUDE PROTEIN 25 % 28.49 % CRUDE FAT - ETHER EXTRACT 9 % 10.58 % AFLATOXIN Satisfactory FUMONISIN 5.68 PPM 20131363 CORN DDG W/SOLUBLES CRUDE PROTEIN 25 % 27.86 % CRUDE FAT - ETHER EXTRACT 9.4 % 11.069 % AFLATOXIN Satisfactory FUMONISIN 5.14 PPM VOMITOXIN 0 PPM 20132841 CORN DDG W/SOLUBLES CRUDE PROTEIN 25 % 26.57 % CRUDE FAT - ETHER EXTRACT 9 % 10.51 % AFLATOXIN Satisfactory 20132842 CORN DDG W/SOLUBLES CRUDE PROTEIN 25 % 26.59 % CRUDE FAT - ETHER EXTRACT 9 % 10.8 % AFLATOXIN Satisfactory ABSORPTION CORP FERNDALE, WA 20131094 CAREFRESH COMPLETE MENU SMALL ANIMAL FOOD - SPECIALLY FORMULATED DI CRUDE PROTEIN 14 % 13.33 % * CRUDE FIBER 15 % 19.97 % MAX - 20 % ACCO FEEDS MINNEAPOLIS, MN 20130933 SHOWMASTER LAMB & GOAT CRUDE PROTEIN 18 % 20.13 % COPPER 16.64 PPM DECOQUINATE 56.75 G/T 58.17 G/T 20132012 PIG BASE MIX CRUDE -

The Zippers Client List

The Zippers Client List The following is a listing of past and current Zippers clients. It is a veritable who’s who of Fortune 500 Companies and Associations in the U.S.A and abroad. Many of these corporate clients have hired The Zippers countless times to entertain their clientele at conventions and trade shows all over the world. In the world of corporate entertainment, The Zippers lead the pack with style, consistency, versatility and professionalism. 7-UP CORPORATION A & A REDI MIX A T & T AARP ABBOT LABS ABBOTT MEDICAL OPTICS ABLE SERVICES AC NIELSON ACADEMY INSURANCE ACCENTURE ACOFP ACTIVE X ACURA ADT SECURITY SYSTEMS ADVANCED MEDICAL OPTICS AFSCME AHRI AIDCO AIRTOUCH ALAMO RENTAL CAR ALFA INT ALLADIN HOTEL LAS VEGAS GRAND OPENING AMBASSADORS NATIONWIDE AMERICAM ACADEMY OF FAMILY PHYSICANS AMERICAN AIRLINES AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF BLOOD BANKS AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF EQUINE PRACTITIONERS AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF ORTHODONDISTS AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION AMERICAN BUSINESS PRESS AMERICAN CASH FLOW ASSOCIATION AMERICAN COLLEGE OF TRIAL LAWYERS AMERICAN COMMUNITY BANKERS AMERICAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION AMERICAN FAMILY INSURANCE AMERICAN FUNDS AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION AMERICAN MEDICAL INSTRUMENTS AMERICAN MILITARY BANK ASSOCIATION AMERICAN NUCLEONICS AMERICAN OPTOMETRIC ASSOCIATION AMERICAN PIPELINE CONTRACTORS ASSOCIATION AMERICAN POSTAL WORKERS AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR AESTHETIC PLASTIC SURGERY AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR BARIATRIC SURGERY AMERICAN TRUCK DEALERS AMERISOURCE BERGEN AMERITAS INSURANCE AMGEN AMT AMWAY AMYLIN PHARMACEUTICALS ANAHEIM AREA -

Stock.Status.Report

PAGE: 1 INVENTORY STOCK STATUS BY BRANCH BY PRODUCT CLASS 02:44:20pm 11 Jan 2016 WHSE: ITEM# PROD.DESC..................... DESC 2.. RECEIPTS RETURNS. QTY.SOLD.LY SALES$.. SALES.. SALES. SALES. ON .... LST.VALUE... COST... MTD... MTD... YTD... YTD.. LM... MTD. HAND... 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 170 0.00 0.000 *** VENDOR.NAME: 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 170 0.00 99700 .EPIC GREEN (LEM LIME) 24/8OZ #4802 0 0 3 0 0 1 0 2 22.98 11.490 99710 .EPIC PURPLE (BLK CHRY) 24/8OZ #4801 0 0 3 0 0 1 0 2 22.98 11.490 99720 .EPIC RED (STRAW MELON) 24/8OZ #4804 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 11.490 9946 EPIC BLUE (BLUE RASP) 24/8OZ #4085 0 0 89 221 17 25 17 38 436.62 11.490 9970 EPIC GREEN (LEMON LIME) 24/8OZ #4802 0 0 398 259 20 23 20 119 1367.31 11.490 9971 EPIC PURPLE(BLK CHERRY) 24/8OZ #4801 0 0 432 259 20 33 20 79 907.71 11.490 9972 EPIC RED (STRAW MELON) 24/8OZ #4804 0 0 438 234 18 30 18 205 2355.45 11.490 9973 EPIC YELLOW(PASSION FRT)24/8OZ #4803 0 0 200 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 11.490 *** VENDOR.NAME: 1 EPIC LLC 0 0 1565 972 75 113 75 445 5113.05 8185 NUTTY RICE BLUEBERRIES 48/.62 #B062ARB 0 0 61 105 5 9 5 42 745.92 17.760 8180 NUTTY RICE CRANBERRIES 48/.62 #B062ARC 126 0 107 126 6 11 6 139 2468.64 17.760 9522 NUTTY RICE MANGO 48/.62 #B062ARM 18 0 62 0 0 0 0 64 1136.64 17.760 *** VENDOR.NAME: 180 SNACKS 144 0 230 231 11 20 11 245 4351.20 6351 BULK CHOCOLATE PEANUTS 25 LB #120FT 0 0 7 0 0 1 0 1 67.50 67.500 6350 BULK CHOCOLATE RAISIN 25 LB #118FT 1 0 11 0 0 1 0 2 168.00 84.000 5756 BULK GUMMIE BEARS 20 LB #102FT 2 0 96 143 3 5 3 2 64.00 32.000 6353 BULK JORDAN ALMOND 25 LB #147B 1 0 13 89 1 -

Mars Petcare Opens First Innovation Center in The

Contacts: Gregory Creasey (615) 807-4239 [email protected] MARS PETCARE OPENS FIRST INNOVATION CENTER IN THE UNITED STATES New $110 Million Gold LEED-Certified Campus Will Serve As Global Center of Excellence for Dry Cat and Dog Food THOMPSON’S STATION, TENN. (October 1, 2014) – Today Mars Petcare officially opened the doors of its new, state-of-the-art, Gold-LEED certified $110 million Global Innovation Center in Thompson’s Station, Tenn. The new campus, designed to help the company Make a Better World for Pets™ through pet food innovations, is the third Mars Petcare innovation center and first in the United States. It will serve as the global center of excellence for the company’s portfolio, which includes five billion dollar brands: PEDIGREE®, WHISKAS®, ROYAL CANIN®, BANFIELD® and IAMS®. The new center joins forces with similar Mars Petcare Global Innovation Centers located in Verden, Germany and Aimargues, France, and will focus on dry cat and dog food in both the natural and mainstream pet food categories. “Everything about this campus is dedicated to helping pets live longer and happier lives,” said Larry Allgaier, president of Mars Petcare North America. “Mars has been doing business in Tennessee for the past 35 years, employing nearly 1,700 Associates across our Petcare, Chocolate and Wrigley business segments. Our $110 million Global Innovation Center marks the sixth Mars site in Tennessee and will employ more than 140 Associates.” The location in Thompson’s Station was selected in part because of a great working relationship with the state of Tennessee, which is already home to Mars facilities in Cleveland, Chattanooga, Lebanon and Franklin (two locations). -

Big Heart Pet Brands Scales with Kenandy

CASE STUDY Big Heart Pet Brands Scales with Kenandy Most of us aren’t ashamed to admit it: our pets rule our roosts. The right ERP platform = simplifying While final numbers aren’t yet in, it’s estimated (by the complexity, enabling growth American Pet Products Association) that Americans spent “One of the main reasons we selected Kenandy was that more than $58 billion on their pets in 2014. And a great many we wanted a flexible system that easily adapts to business of those cats and dogs were scarfing down food and treats changes, such as new acquisitions, while also ofering from Big Heart Pet Brands (formerly Del Monte Corporation enterprise-class capabilities,” explains Dave McLain, and now part of the J.M. Smucker Company). Senior Vice President, Chief Information Ofcer, and Chief Big Heart Pet Brands is the largest standalone producer, Procurement Ofcer at Big Heart Pet Brands. distributor, and marketer of premium-quality, branded pet Big Heart consolidated some 90 legacy applications onto the food and snacks in the United States, with annual sales of $2.3 Kenandy ERP cloud and the Salesforce1 Platform. They are billion. Their industry-leading products include such perennial now running their entire operations on the new cloud system, pet favorites as Milk-Bone®, 9Lives®, Gravy Train®, Kibbles ‘n including their corporate financials, five manufacturing Bits®, Meow Mix®, and Natural Balance®. facilities, and 11 warehouse operations, as well as connecting Ofering a variety of products and lines of business is great directly to more than 20 co-packer facilities and Big Heart for pleasing picky (and pampered) pets, but Big Heart customers across the country. -

Welby Gardens Price List- 2017 Level 3 Phone: 303-288-3398 Fax: 303-287-9316 Email: [email protected] Web

Welby Gardens Price List- 2017 Level 3 Phone: 303-288-3398 Fax: 303-287-9316 Email: [email protected] Web: http://hardyboyplant.com Company: ____________________________ Ordered By: _______________ Phone No.: _______________ Date Order Will Be: Picked Up/Delivered _____________ PO No.: ____________ Variety Qty Variety Qty Variety Qty Variety Qty Annuals Impatien Dazzler Salmon- 18/4pak Pansy Frizzle Sizzle Mix - 18/4pak Pansy Panola True Blue - 18/4pak 18/4pak LC Red $20.52 Impatien Hardy Boy Mix- 18/4pak Pansy Frizzle Sizzle Orange - 18/4pak Pansy Rockies Purple - 18/4pak Alyssum Clr Crystal Lavender Shad - 18/4pak Impatien Passionberry Mix- 18/4pak Pansy Grandio Blotched Mix - 18/4pak Pansy Royal Gold Mix - 18/4pak Alyssum Clr Crystal Mix - 18/4pak Impatien Spr Elfin Sedona Mix- 18/4pak Pansy Grandio Clear Mix - 18/4pak Pansy Solar Flare Mix - 18/4pak Alyssum Clr Crystal Purple Shades - 18/4pak Lobelia Cobalt Blue - 18/4pak Pansy Grandio Clear Purple - 18/4pak Pansy Ultima Morpho - 18/4pak Alyssum Clr Crystal White - 18/4pak Lobelia Palace Sky Blues - 18/4pak Pansy Grandio Deep Blue w/Blotch - 18/4pak Petunia Aladdin Cherry - 18/4pak Alyssum Easter Bonn Dp Rose - 18/4pak Lobelia Riviera Blue Sky - 18/4pak Pansy Grandio Yellow w/Blotch - 18/4pak Petunia Carpet Blue Lace - 18/4pak Dianthus Ideal Select Mix - 18/4pak Lobelia Riviera Blue/Wht Eye - 18/4pak Pansy Inspire Primrose - 18/4pak Petunia Carpet Blue Sky - 18/4pak Dianthus Ideal Select Red - 18/4pak Lobelia Riviera Lilac - 18/4pak Pansy Inspire Prple/Orng - 18/4pak Petunia