Cupola 2017- 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE KATHERINE V8 FR.Indd 1 25/06/2020 3:29 PM PRESS RELEASE KATHERINE V8 FR.Inddpress 2

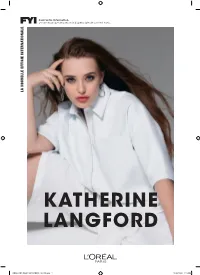

Pour votre information. Le communiqué de presse indispensable de L’Oréal Paris. LA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE INTERNATIONALE KATHERINE LANGFORD PRESS RELEASE_KATHERINE_V8_FR.indd 1 25/06/2020 3:29 PM Pour votre information. Le communiqué de presse indispensable de L’Oréal Paris. L’ORÉAL PARIS A L’IMMENSE “Nous sommes heureux d’accueillir Katherine dans la PLAISIR DE PRÉSENTER famille L’Oréal Paris. Elle est un modèle pour nous toutes, une jeune femme talentueuse et sûre d’elle qui utilise sa SA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE tribune pour une influence positive. L’étoile de Katherine ne fera que monter. En tant que jeune héroïne rayonnante INTERNATIONALE, qui encourage les gens à croire en eux-mêmes, elle est l’effigie parfaite pour incarner notre message de marque : KATHERINE LANGFORD. nous en valons tous la peine. ” Delphine Viguier-Hovasse ICÔNE MILLÉNAIRE Présidente de la marque mondiale L’Oréal Paris Audacieuse et sûre d’elle, Katherine Langford a déjà une grande influence sur sa génération. Cette actrice montante est, surtout, connue pour son rôle de ‘Hannah Baker’ dans la série 13 Reasons Why. Elle est également célèbre car elle a incarné, à l’écran, des jeunes femmes fortes. Aussi bien dans un rôle ou dans sa propre vie, elle s’est révélée battante s’exprimant pour RINE la tolérance et sensibilisant à l’égalité des sexes. Utilisant son LA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE INTERNATIONALE influence, elle a notamment encouragé les conversations en ligne sur le manque de confiance en soi, elle est déjà devenue un modèle inspirant pour beaucoup de femmes. À seulement 24 ans, elle incarne parfaitement les valeurs de L’Oréal Paris avec sa joie de vivre, son talent et ses convictions ; la marque est fière d’accueillir Katherine dans la famille. -

Suicide Watch: How Netflix Landed on a Cultural Landmine

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Capstones Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Fall 12-16-2018 Suicide Watch: How Netflix Landed on a Cultural Landmine Shabnaj Chowdhury How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gj_etds/319 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Suicide Watch: How Netflix Landed on a Cultural Landmine By Shabnaj Chowdhury In retrospect, perhaps it’s not surprising that Netflix didn’t seem to see it coming. A week before the first season of “13 Reasons Why” dropped on the streaming service on March 31, 2017, positive reviews began coming in from television critics. “A frank, authentically affecting portrait of what it feels like to be young, lost, and too fragile for the world,” wrote Entertainment Weekly’s Leah Greenblatt. The L.A. Time’s Lorraine Ali also gave a rave review, saying the show “is not just about internal and personal struggles—it's also fun to watch.” But then the show debuted, and suddenly the tenor of the conversation changed. Executive-produced by Brian Yorkey and pop star Selena Gomez, “13 Reasons Why” centers around the suicide of 17-year-old Hannah Baker (Katherine Langford), a high-school junior who leaves behind a series of audiotapes she recorded, detailing the thirteen reasons why she decided to kill herself. Over the course of thirteen one-hour episodes, we learn about the events leading up to Hannah’s death, as she dedicates each tape to a person she feels has wronged her, including Clay Jensen (Dylan Minnette), her friend, and whose perspective is interwoven with Hannah’s, offering two timelines between the past when Hannah was alive, and the present day, two weeks after her death. -

“The Incompatible Tape:” Exploring the Limits of Adaptation in 13

“THE INCOMPATIBLE TAPE:” EXPLORING THE LIMITS OF ADAPTATION IN 13 REASONS WHY A Thesis by ANDREW NGUYEN ZALOT Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Chair of Committee, Anne Morey Committee Members, Claudia Nelson Daniel Humphrey Head of Department, Maura Ives May 2020 Major Subject: English Copyright 2020 Andrew Nguyen Zalot ABSTRACT This research explores the ways in which a novel can experience a reevaluation as a result of it receiving a television adaptation that results in its textual and contextual elements being reexamined. Jay Asher’s Thirteen Reasons Why and its Netflix adaptation written by Brian Yorkey serve as the case study for this research, with the two works and their contextual material such as the novel’s paratexts and adaptation’s online resources being the primary materials examined. I argue that since the premiere of Yorkey’s series, the novel has experienced a reevaluation that demonstrates the limitations of translating certain narrative techniques from a novel to a television series and how the novel laid the groundwork for the therapeutic experience the show sets out to create for viewers. I examine the contextual elements of the novel and its adaptation to understand how the novel’s efforts to create a community and therapeutic experience for its readers was used by the Netflix series for its own efforts to promote prosocial behavior and the formation of community among its viewers. I also explore the changes made in the Netflix series and how the novel’s epistolary narration was altered to accommodate the narrative standards of a television series. -

Newspaper Does Technology Help Or Harm Us People Use the It Also Can Make People Internet for a Variety of Depressed

Norfolk High School Panther- 801 Riverside Blvd. - Norfolk, NE 68701 - Volume 72 - Issue 8 - May 17, 2017 Newspaper Does technology help or harm us People use the it also can make people internet for a variety of depressed. Recent studies thing like buying things from the University of online, doing homework, Pittsburgh School of and using social media. Medicine show that a Everyone has everything heavy use of social media they need at their can have a negative effect fingertips. But although we on your mental health. have access to a world of The report also states information, not everyone that multiple studies uses it to their advantage. have linked social media The internet has changed with declines in mood, how people stand up for sense of well-being, themselves, talk to each and life satisfaction. But other, and how we take those aren’t the only care of ourselves. From negatives that come with tablets to smartphones, technology; isolation, lack laptops to apple watches, of social skills, obesity, people have gained so poor sleep habits, lack much by the internet but of privacy, stress, lack of we have also lost a lot too. boundaries, and addiction “Whatever dating This chart shows the percentage of Americans that have each de- habits are all symptoms site you use, you ‘meet’ vice. Cell phones are most popular in America and tablets are sur- of being addicted to someone and immediately prisingly the least likely device. Chart by Statistics New Zealand. technology. start fantasizing about A l t h o u g h them, because it can be by Robyn Breen Shinn just having a phone visible intimacy and understanding technology has changed more fun than reality, I see says that technology in the room, even if no one during face-to-face time the way we communicate, people delaying meeting changes how we act in a checked it, made people with someone. -

Hollywood Foreign Press Association 2018 Golden Globe Awards for the Year Ended December 31, 2017 Press Release

HOLLYWOOD FOREIGN PRESS ASSOCIATION 2018 GOLDEN GLOBE AWARDS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2017 PRESS RELEASE 1. BEST MOTION PICTURE – DRAMA a. CALL ME BY YOUR NAME Frenesy Film / La Cinéfacture Productions / Water’s End Productions; Sony Pictures Classics b. DUNKIRK Warner Bros. Pictures / Syncopy; Warner Bros. Pictures c. THE POST DreamWorks Pictures, Twentieth Century Fox d. THE SHAPE OF WATER Double Dare You; Fox Searchlight Pictures e. THREE BILLBOARDS OUTSIDE EBBING, MISSOURI Blueprint Pictures; Fox Searchlight Pictures 2. BEST PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE – DRAMA a. JESSICA CHASTAIN MOLLY'S GAME b. SALLY HAWKINS THE SHAPE OF WATER c. FRANCES MCDORMAND THREE BILLBOARDS OUTSIDE EBBING, MISSOURI d. MERYL STREEP THE POST e. MICHELLE WILLIAMS ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD HOLLYWOOD FOREIGN PRESS ASSOCIATION 2018 GOLDEN GLOBE AWARDS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2017 PRESS RELEASE 3. BEST PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTOR IN A MOTION PICTURE – DRAMA a. TIMOTHÉE CHALAMET CALL ME BY YOUR NAME b. DANIEL DAY-LEWIS PHANTOM THREAD c. TOM HANKS THE POST d. GARY OLDMAN DARKEST HOUR e. DENZEL WASHINGTON ROMAN J. ISRAEL, ESQ. 4. BEST MOTION PICTURE – MUSICAL OR COMEDY a. THE DISASTER ARTIST Good Universe / Point Grey / Ratpac-Dune / WB/New Line Pictures; A24 b. GET OUT Blumhouse / QC Entertainment / Monkeypaw Productions; Universal Pictures c. THE GREATEST SHOWMAN Twentieth Century Fox; Twentieth Century Fox d. I, TONYA Clubhouse Pictures / LuckyChap Entertainment; NEON e. LADY BIRD IAC Films; A24 HOLLYWOOD FOREIGN PRESS ASSOCIATION 2018 GOLDEN GLOBE AWARDS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2017 PRESS RELEASE 5. BEST PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE – MUSICAL OR COMEDY a. -

Compelling Characters

Master’s Thesis ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Compelling Characters An analysis and discussion of the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why in relation to character engagement and the depiction of suicide ________________________________________________________________________________ Helene Knudsen Advisor: Brian Russell Graham Keywords: 13 Reasons Why, Suicide, media, influence, culture, character engagement Warning: Be aware that the assignment contains a graphic picture of suicide Abstract The following thesis seeks to examine how the popular, original Netflix TV-series called 13 Reasons Why ensures character engagement. The project was conducted using Gary Solomon´s work within the field of cinematherapy while exploring the potential benefits of the series and its therapeutic value. Moreover, this thesis also incorporates the cognitivist approach by Jason Mittell when creating a formal analysis of the main characters, named Clay Jensen and Hannah Baker. The analysis showed that most viewers likely experience feelings of engagement and not necessarily identification towards the characters. Finally, a discussion is offered regarding the potential helpful and harmful effects of the graphic and highly criticised suicide scene presented in season one, as well as implications for future research in terms of the medial responsibility. A more nuanced discussion is offered regarding the depiction of suicide in the media since the press seems to focus on the negative results -

Black Panther’

20 Established 1961 Wednesday, June 20, 2018 Lifestyle Awards (From left) Actors Finn Wolfhard, Noah Schnapp, Sadie Sink and Gaten Actor and show host Tiffany Haddish accepts the Best Host Tiffany Haddish performs onstage.— AFP photos Matarazzo attending the 2018 MTV Movie & TV awards, at the Barker Comedic Performance award for ‘Girls Trip’ onstage. Hangar in Santa Monica. ‘Black Panther’ Actor Chadwick Boseman accepts the Best Hero award for ‘Black Panther’ onstage dur- ing the 2018 MTV Movie And TV Awards at star honors real-life Barker Hangar in Santa Monica, California. hero at MTV awards andmark blockbuster “Black Panther” and James Shaw Jr., he fought off a gunman in Antioch, nostalgic horror sensation “Stranger Tennessee, at a Waffle House. He saved lives,” he Things” shared the spoils Monday with a said. Shaw singlehandedly wrestled the AR-15 real-life hero at the MTV Movie and TV semi-automatic rifle from the hands of Travis LAwards. Marvel’s “Black Panther” racked up four Reinking as he was allegedly reloading in the mid- awards, including best movie. Its star, Chadwick dle of a shooting rampage in April. Boseman, won best hero and best movie perform- Four people were killed and two others wound- ance while his nemesis Michael B Jordan was ed at the Waffle House restaurant in Nashville, named best villain. Boseman, 40, got his hero stat- America’s country music capital. But Shaw has uette from presenters Olivia Munn and Zazie been credited with saving many more lives. He suf- Beetz-and promptly gave it to James Shaw Jr., the fered a graze wound from a bullet and burns on his man who stopped a mass shooter at a Tennessee right hand from grabbing the hot barrel of the gun. -

Rogen, Keaton to Star in John Mcafee Movie

13 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 28, 2018 HUNTER KILLER JUFFAIR DAILY AT: 10.45 AM + 3.00 + 7.15 + JASON STATHAM, RUBY ROSE, BINGBING LI 11.30 (PG-15) (ACTION/THRILLER) NEW CITYCENTRE DAILY AT: 11.30 AM + 1.45 + 4.00 GERARD BUTLER, COMMON SEEF (I) DAILY AT: 12.30 + 2.45 + 5.00 + 7.15 + + 6.15 + 8.30 + 10.45 PM 9.30 + 11.45 PM Rogen, Keaton to star JUFFAIR DAILY AT (ATMOS): 10.45 AM + 1.15 + A STAR IS BORN 3.45 + 6.15 + 8.45 + 11.15 PM VENOM (15+) (DRAMA/ROMANTIC/MUSICAL) DAILY AT: 10.30 AM + 1.00 + 3.30 + 6.00 + 8.30 (PG-15) (ACTION/ADVENTURE) LADY GAGA, SAM ELLIOTT + 11.00 PM TOM HARDY, RIZ AHMED CITYCENTRE DAILY AT: 11.30 AM + 2.00 + CITYCENTRE DAILY AT: 12.30 + 3.15 + 6.00 + in John McAfee movie 4.30 + 7.00 + 9.30 PM + 12.00 MN + (1.00 AM JUFFAIR DAILY AT: 11.00 AM + 1.30 + 4.00 + 8.45 + 11.30 PM THURS/FRI) 6.30 + 9.00 + 11.30 PM DAILY AT (ATMOS): 11.30 AM + 2.00 + 4.30 + CITYCENTRE DAILY AT: 11.15 AM + 1.45 + 4.15 + THE KING OF THIEVES IANS | Los Angeles 7.00 + 9.30 PM +12.00 MN, DAILY AT VIP (I): 6.45 + 9.15 + 11.45 PM (PG-15) (CRIME/DRAMA) NEW 11.00 AM + 1.30 + 4.00 + 6.30 + 9.00 + 11.30 PM, WADI AL SAIL DAILY AT: 11.45 AM + 2.00 + 4.15 MICHAEL CAINE, MICHAEL GAMBON ctors Seth Rogen and DAILY AT VIP (II): 10.30 AM + 1.00 + 3.30 + 6.00 + 6.30 + 8.45 + 11.00 PM + 8.30 + 11.00 PM SEEF (II) DAILY AT: 12.15 + 2.30 + 4.45 + 7.00 + Michael Keaton will star JOHNNY ENGLISH STRIKES AGAIN 9.15 + 11.30 PM in “King of the Jungle”, SEEF (II) DAILY AT: 11.15 AM + 12.30 + 1.45 + A 3.00 + 4.15 + 5.30 + 6.45 + 8.00 + 9.15 + 10.30 + (PG) (COMEDY/ACTION/ADVENTURE) a comedy about the true story BOARDING SCHOOL 11.45 PM + (1.00 AM THURS/FRI) ROWAN ATKINSON, OLGA KURYLENKO of tech magnate John McAfee. -

Vidolova Thesis 2020

Copyright by Latina Sabinova Vidolova 2020 The Thesis Committee for Latina Sabinova Vidolova Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Thesis: To All the Audiences I’ve Tweeted to Before: Netflix, Teen Girls, and Social Media Marketing APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Alisa Perren, Supervisor Suzanne Scott To All the Audiences I’ve Tweeted to Before: Netflix, Teen Girls, and Social Media Marketing by Latina Sabinova Vidolova Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my committee members, Alisa Perren and Suzanne Scott, for offering their time and input on this project. They have oriented me toward generative questions, propelled my analysis, and set me on scholarly trajectories that will inform my work in years to come. iv Abstract To All the Audiences I’ve Tweeted to Before: Netflix, Teen Girls, and Social Media Marketing Latina Sabinova Vidolova, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2020 Supervisor: Alisa Perren In the late 2010s, Netflix assembled a significant collection of teen-centric media on its service, which it extensively promoted on Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. This thesis examines Netflix’s relationship with teen audiences as framed in the social media marketing materials for 13 Reasons Why (2017–2020) and To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before (2018), as well as in the service’s intra-industrial communication and engagements with press from 2016 to 2020. -

Katherine Langford

KATHERINE LANGFORD Comunicado de prensa París, Francia Contactos: Araceli Becerril Comunicación PR & Digital L’Oréal (55) 59 99 56 00 ext. 6054 [email protected] Gabriela Barradas Espacio en medio (55) 86 23 55 38 [email protected] L’ORÉAL PARIS SE COMPLACE EN PRESENTAR A KATHERINE LANGFORD COMO SU NUEVA EMBAJADORA INTERNACIONAL. ICONO MILLENIAL Audaz y segura de sí, Katherine Langford ya ha generado un gran impacto en su generación. La actriz en ascenso es conocida por su interpretación como Hannah Baker en la serie 13 Reasons Why y por tomar un fuerte protagonismo ante las mujeres jóvenes. Ella tiene el mismo poder tanto dentro como fuera de la pantalla, alzando la voz por la tolerancia y elevando la conciencia sobre la igualdad de género. Usando su alcance para crear conversaciones en línea sobre problemas de confianza, ya se ha convertido en un modelo positivo para todas las mujeres. Con tan solo 24 años, ella encarna perfectamente los valores de L'Oréal Paris con su positividad, su talento y sus convicciones. Como marca nos enorgullece darle la bienvenida a Katherine a la familia. “Nos complace darle la bienvenida a Katherine a la familia L’Oréal Paris. Ella es una modelo a seguir; una mujer talentosa y segura usando su plataforma para influenciar de manera positiva. La estrella que es Katherine seguirá solo en ascenso. Como una heroína joven y radiante que anima a las personas a creer en sí mismas, ella es la embajadora perfecta para encarar el mensaje distintivo de nuestra marca: todas lo valemos.” - Delphine Viguier-Hovasse, Presidenta de Marca Global de L’Oréal Paris. -

SYNOPSIS Everyone Deserves a Great Love Story. but for Seventeen

SYNOPSIS Everyone deserves a great love story. But for seventeen-year old Simon Spier it’s a little more complicated: he’s yet to tell his family or friends he’s gay and he doesn’t actually know the identity of the anonymous classmate he’s fallen for online. Resolving both issues proves hilarious, terrifying and life-changing. Directed by Greg Berlanti (Everwood, The Flash, Riverdale), with a screenplay by Elizabeth Berger & Isaac Aptaker, and based on Becky Albertalli’s acclaimed novel, LOVE, SIMON is a funny and heartfelt coming-of-age story about the thrilling ride of finding yourself and falling in love. THE BOOK LOVE, SIMON was adapted from Becky Albertalli’s young adult novel Simon vs The Homo Sapien’s Agenda. Published in January 2012, the book won the William C. Morris Award for Best Young Adult Debut of the Year and was included in the National Book Award Longlist. Albertalli never imagined that her book would be published let alone become an award-winning 1 bestseller and now a major motion picture: “I was a psychologist when I wrote the book,” she says. “I was the mother of a one-year-old, now four-year-old. I was writing during his nap times. I had always wanted to write a book, and decided I would give it a try. I don’t know where my idea for the plot came from, but the characters had been kicking around in my head for some time. I had this image of a messy-haired, gay kid in a hoodie, and that turned out to be Simon.