Vidolova Thesis 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

Orientalism Within the Creation and Presentation of Doctor Strange

Sino-US English Teaching, May 2021, Vol. 18, No. 5, 131-135 doi:10.17265/1539-8072/2021.05.007 D DAVID PUBLISHING Orientalism Within the Creation and Presentation of Doctor Strange XU Hai-hua University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Doctor Strange has become a representation of superheroes with magic in the world of Marvel. Considering his identity as Sorcerer Supreme, there is a crucial connection between the Orient and his magic. The paper will discuss the detailed symbols of Orientalism in the process of creation and presentation of Doctor Strange respectively to figure out the change of Orientalism with the times within the texts of Doctor Strange and its existence today. Keywords: Orientalism, Doctor Strange, magic in the world of Marvel Introduction Ever since his debut in 1963, Doctor Strange has become a representation of superheroes with magic in the world of Marvel. Noticeably, a number of eastern elements have never ceased to appear in the Doctor Strange series throughout the times. Several characters are from the east, and the mysterious Asian land is also the birthplace of Doctor Strange’s magic power. Considering his identity as Sorcerer Supreme, the first and strongest sorcerer in Marvel, there must be a crucial connection between the Orient and his magic, both in the entire Marvel world, and in traditional western culture. Eastern elements under the account of westerners can be well interpreted with reference to the general concept of Orientalism. Thus, this paper aims to discuss the way the idea of Orientalism evolves with the times that is showcased within the texts of Doctor Strange. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Q2 2020 Letter to Shareholders

July 16, 2020 Fellow shareholders, We live in uncertain times with restrictions on what we can do socially and many people are turning to entertainment for relaxation, connection, comfort and stimulation. In Q1 and Q2, we saw significant pull-forward of our underlying adoption leading to huge growth in the first half of this year (26 million paid net adds vs. prior year of 12 million). As a result, we expect less growth for the second half of 2020 compared to the prior year. As we navigate these turbulent circumstances, we’re focused on our members by continuing to improve the quality of our service and bringing new films and shows to people's screens. Our Q2 summary results and forecast for Q3 are in the table below. Ted Sarandos appointed co-CEO and elected to Board of Directors Ted joined Netflix over 20 years ago, and we are thrilled to appoint him to be co-CEO with Reed. “Ted has been my partner for decades. This change makes formal what was already informal -- that Ted and I share the leadership of Netflix,” says Hastings. Lead Independent director Jay Hoag says “Having watched Reed and Ted work together for so long, the board and I are confident this is the right step to evolve Netflix’s management structure so that we can continue to best serve our members and shareholders for years to come.” 1 Ted will also continue to serve as Chief Content Officer. In addition, Greg Peters has been appointed COO adding to his Chief Product Officer role. -

WORST COOKS in AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios

Press Contact: Lauren Sklar Phone: 646-336-3745; Email: [email protected] WORST COOKS IN AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios MINDY COHN Mindy Cohn made her acting debut as the witty, precious Eastland Academy student Natalie Green in the hit comedy series The Facts of Life. She was discovered while attending Westlake School for Girls in Bel Air, California, when actress Charlotte Rae and producer Norman Lear came to the school to authenticate scripts for their new show. Ms. Rae was so taken with the vivacious eighth grader she convinced producers to create a role for her. Mindy remained on the show for all nine seasons, also traveling to Paris and Australia with her co-stars to produce two successful television movies based on the series. Concurrently, with her role in Facts, Mindy played “Rose Jenko” in Fox’s 21 Jump Street. Other notable television appearances included Diff’rent Strokes, Double Trouble, Charles in Charge, Dream On and Suddenly Susan. In 1983, Mindy appeared in her first professional stage performance in Table Settings, written and directed by James Lapine and filmed for HBO Television. The illustrious cast included Eileen Heckart, Stockard Channing, Robert Klein, Peter Riegart, and Dinah Manoff. She went on to make her feature film debut in The Boy Who Could Fly, which co-starred Colleen Dewhurst, Fred Gwynne and Fred Savage. Mindy took a hiatus from her career to attend university, where she earned a Bachelor’s degree in Cultural Anthropology and a Masters in Education. During this time, she studied improvisation and scene work with Gary Austin and Larry Moss. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

Serie Netflix 13 Reasons Why: Consideraciones Para Educadores

Serie Netflix 13 Reasons Why: Consideraciones para Educadores Las escuelas desempeñan un papel importante en la prevención del suicidio de los jóvenes, y la toma de conciencia de los posibles factores de riesgo en la vida de los estudiantes es vital para esta responsabilidad. La serie de moda de Netflix 13 Reasons Why (13 Razones por qué), basada en una novela de adultos jóvenes del mismo nombre, está planteando tales preocupaciones. La serie gira alrededor de Hannah Baker, de 17 años de edad, quien se quita la vida y deja grabaciones de audio para 13 personas que dice de alguna manera fueron parte de por qué se suicidó. Cada cinta relata acontecimientos dolorosos en los cuales uno o más de los 13 individuos desempeñaron un papel. Los productores del programa dicen que esperan que la serie ayude a los que pueden estar luchando con pensamientos de suicidio. Sin embargo, la serie, que muchos adolescentes están viendo en exceso sin la orientación y el apoyo de adultos, está planteando preocupaciones de expertos en prevención de suicidios sobre los riesgos potenciales que plantea el tratamiento sensacionalista del suicidio juvenil. La serie representa gráficamente una muerte por suicidio y aborda en detalle desgarrador una serie de temas difíciles, tales como la intimidación, la violación, el conducir ebrio y la vergüenza. La serie también destaca las consecuencias de que los adolescentes sean testigos de agresión e intimidación (es decir, espectadores) y no tomen medidas para resolver la situación (por ejemplo, no hablar en contra del incidente, no decirle a un adulto sobre el incidente). -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

PRESS RELEASE KATHERINE V8 FR.Indd 1 25/06/2020 3:29 PM PRESS RELEASE KATHERINE V8 FR.Inddpress 2

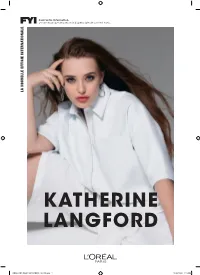

Pour votre information. Le communiqué de presse indispensable de L’Oréal Paris. LA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE INTERNATIONALE KATHERINE LANGFORD PRESS RELEASE_KATHERINE_V8_FR.indd 1 25/06/2020 3:29 PM Pour votre information. Le communiqué de presse indispensable de L’Oréal Paris. L’ORÉAL PARIS A L’IMMENSE “Nous sommes heureux d’accueillir Katherine dans la PLAISIR DE PRÉSENTER famille L’Oréal Paris. Elle est un modèle pour nous toutes, une jeune femme talentueuse et sûre d’elle qui utilise sa SA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE tribune pour une influence positive. L’étoile de Katherine ne fera que monter. En tant que jeune héroïne rayonnante INTERNATIONALE, qui encourage les gens à croire en eux-mêmes, elle est l’effigie parfaite pour incarner notre message de marque : KATHERINE LANGFORD. nous en valons tous la peine. ” Delphine Viguier-Hovasse ICÔNE MILLÉNAIRE Présidente de la marque mondiale L’Oréal Paris Audacieuse et sûre d’elle, Katherine Langford a déjà une grande influence sur sa génération. Cette actrice montante est, surtout, connue pour son rôle de ‘Hannah Baker’ dans la série 13 Reasons Why. Elle est également célèbre car elle a incarné, à l’écran, des jeunes femmes fortes. Aussi bien dans un rôle ou dans sa propre vie, elle s’est révélée battante s’exprimant pour RINE la tolérance et sensibilisant à l’égalité des sexes. Utilisant son LA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE INTERNATIONALE influence, elle a notamment encouragé les conversations en ligne sur le manque de confiance en soi, elle est déjà devenue un modèle inspirant pour beaucoup de femmes. À seulement 24 ans, elle incarne parfaitement les valeurs de L’Oréal Paris avec sa joie de vivre, son talent et ses convictions ; la marque est fière d’accueillir Katherine dans la famille. -

13 Reasons Why: Plot Summary and Content Warnings

13 Reasons Why: Plot summary and content warnings If you haven’t seen 13 Reasons Why but want to discuss it with a young person, or are trying to decide whether it is suitable viewing for a young person in your care, this summary may help. It covers the basic plot and describes content that viewers may find disturbing. 13 Reasons Why is not consistent with many guidelines for media reporting and depiction of suicide, and watching it may be distressing for young people, especially those who are vulnerable. 13 Reasons Why is a high school based drama recently released internationally on Netflix. All 13 hour-long episodes were released together, on March 31st 2017. It is the story of Hannah, a young woman who has died by suicide before the show starts. She has left a box of audio-tapes with Clay, the protagonist of the show, each revealing one of the 13 reasons why she decided to die. On the tapes, she details a number of highly traumatic events that contributed to her developing thoughts of suicide, mostly involving her classmates. Clay is the last of several people who were to listen to the tapes, according to her instructions. As Clay plays them, he learns about many things that happened during Hannah’s life. Classmates who have already heard the tapes are involved at various points, providing additional (sometimes conflicting) information and trying to Keep him on tracK. On the surface, the show clearly set out to do something important, liKe the novel of the same name; to show that actions have consequences. -

MAHS/MASC Newsletter 1

NOVEMBER 2020 VOLUME 1 MAHS/MASC Newsletter THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER FROM THE MINNESOTA ASSOCIATION OF HONORS SOCIETIES AND STUDENT COUNCILS In the Newsletter: EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR'S REPORT FROM DOUG ERICKSON- 2 --------------- PRESIDENTIAL WELCOME LETTER- 3 --------------- EXECUTIVE BOARD BIOS AND WELCOME- 4 --------------- DIVISION SPOTLIGHT- Our First Newsletter! CENTRAL AND SOUTH On behalf of the MAHS/MASC Executive board, our EASTERN- 7 wonderful advisors and co-coordinators, we are so --------------- excited to release our first newsletter (hopefully of many!) for the year. We all hope you are staying safe STATE SERVICE and healthy in this unpredictable time. PROJECT REVEAL- 8 --------------- Enjoy the newsletter! 2021 STATE CONVENTION Follow our socials! INFORMATION- 9 @masc_mahsmn MAHS/MASC NEWSLETTER PAGE 1 NOVEMBER 2020 VOLUME 1 Executive Director's Report Presented by Doug Erickson Happy Thanksgiving! It takes a little creativity to find the "thanks" in this year's Thanksgiving. That being said, I am thankful to the strong start to a year with a whole new set of rules. We had our first virtual election and the result is an incredibly strong and creative MAHS/MASC Executive Committee. You will meet all of them in this newsletter edition. Sartell will host the 20-21 MAHS/MASC state convention on April 17-19. The convention coordinators are planning a strong convention. Ted Wiese, Ted Talks, will be our keynote speaker. Ted was set to keynote The Forum this November but Covid took that out. At this time I hope to have this be an "in person" convention. The Executive Committee has decided on a state service project that will recognize the needs that have been created by the pandemic.