Suicide Watch: How Netflix Landed on a Cultural Landmine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

STARDUST 2021.Pdf

S t a r d u s t ~ ‘21 E d i t i o n “He told me to look at my hand, for a part of it came from a star that exploded too long ago to imagine. This part of me was formed Stardust from a tongue of fire that screamed through the heavens until there was our sun. And this small part of me was then a whisper of the earth. When there was life, perhaps this part got lost in a fern that was crushed and covered until it was coal. And then it was a diamond millions We are all of years later, as beautiful as the star from which it miracles, had first come.” wrought from Paul Zindel the dust of stars. -The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds- The editorial staff of Stardust assumes that all creative submissions are works of fiction. Therefore, any resemblances to real people, settings, and events are either coincidental or the responsibility of the student authors, who upon submission to the Stardust staff give the school the right to edit their work and to publish their work for non-profit purposes either through the district website or in print via other student publications. Stardust is the Annual Literary Magazine of Tyrone Area High School Produced by Tyrone High Students 1 . Page S t a r d u s t ~ ‘21 E d i t i o n Page Title Author 3 More Dating, Less Hating Madalynn Cherry 5 GMO-Free? Really? Taylor Black 8 Can You Spare Some Change? Alyssa Luciano 11 Let’s Leave the Left Wade Hendrickson 14 The Death of Creativity Aden McCracken 17 Our Town Lucia Isenberg 20 Anti-Vax is Anti-Kid Hollie Keller 23 Trophy, Anyone? Madison Coleman 26 Human Abnormalities Hollie Keller 31 The Pillow-Talk of Politics Anna-Lynn Fryer 34 Disconnected Miranda Goodman 44 Does the U.S. -

Please Be Aware of Some Concerns Over the “Thirteen Reasons Why” Videos That Have Become Available

Please be aware of some concerns over the “Thirteen Reasons Why” videos that have become available. Article: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/13-reasons-why-mental-health- portrayal_us_58f65f6ae4b0bb9638e70390 Also information from the Connecticut School Counselors Association: Dear CSCA Members, As many of you may have heard by now, “13 Reasons Why” a novel by Jay Asher, is now a series on Netflix. In this series, Hannah Baker, the main character, dies by suicide and leaves 13 cassette tapes outlining the 13 reasons why she did what she did. The series has a different tone than the book, and outlines in graphic detail, topics of suicide, rape, sexual assault, slut shaming and bullying. There have been many concerns about this series by several suicide prevention and mental health organizations about the content and graphic nature of the series. Concerns have also been raised about the lack of support that was offered to Hannah by the adults in her life, including by the school counselor. Unfortunately, the school counselor in this series is not portrayed in a positive light and may lead some to believe that is how professionals in the field may handle a similar situation. The series could be particularly troubling for students who may have already thought about suicide or whose mental health is particularly fragile. If students are going to watch the series, it may be best if they had an adult with whom they could process it with. It is also important for students to walk away understanding that there are many caring adults out there who will help if they find themselves in a situation similar to Hannah’s and they should seek out those supports. -

Sam Urdank, Resume JULY

SAM URDANK Photographer 310- 877- 8319 www.samurdank.com BAD WORDS DIRECTOR: Jason Bateman CAST: Jason Bateman, Kathryn Hahn, Rohan Chand, Philip Baker Hall INDEPENDENT FILM Allison Janney, Ben Falcone, Steve Witting COFFEE TOWN DIRECTOR: Brad Campbell INDEPENDENT FILM CAST: Glenn Howerton, Steve Little, Ben Schwartz, Josh Groban Adrianne Palicki TAKEN 2 DIRECTOR: Olivier Megato TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (L.A. 1st Unit) CAST: Liam Neeson, Maggie Grace,,Famke Janssen, THE APPARITION DIRECTOR: Todd Lincoln WARNER BRO. PICTURES (L.A. 1st Unit) CAST: Ashley Greene, Sebastian Stan, Tom Felton SYMPATHY FOR DELICIOUS DIRECTOR: Mark Ruffalo CORNER STORE ENTERTAINMENT CAST: Christopher Thornton, Mark Ruffalo, Juliette Lewis, Laura Linney, Orlando Bloom, Noah Emmerich, James Karen, John Caroll Lynch EXTRACT DIRECTOR: Mike Judge MIRAMAX FILMS CAST: Jason Bateman, Mila Kunis, Kristen Wiig, Ben Affleck, JK Simmons, Clifton Curtis THE INVENTION OF LYING DIRECTOR: Ricky Gervais & Matt Robinson WARNER BROS. PICTURES CAST: Ricky Gervais, Jennifer Garner, Rob Lowe, Lewis C.K., Tina Fey, Jeffrey Tambor Jonah Hill, Jason Batemann, Philip Seymore Hoffman, Edward Norton ROLE MODELS DIRECTOR: David Wain UNIVERSAL PICTURES CAST: Seann William Scott, Paul Rudd, Jane Lynch, Christopher Mintz-Plasse Bobb’e J. Thompson, Elizabeth Banks WITLESS PROTECTION DIRECTOR: Charles Robert Carner LIONSGATE CAST: Larry the Cable Guy, Ivana Milicevic, Yaphet Kotto, Peter Stomare, Jenny McCarthy, Joe Montegna, Eric Roberts DAYS OF WRATH DIRECTOR: Celia Fox FOXY FILMS/INDEPENDENT -

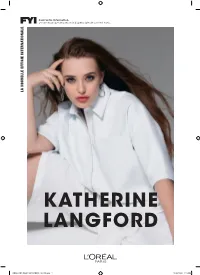

PRESS RELEASE KATHERINE V8 FR.Indd 1 25/06/2020 3:29 PM PRESS RELEASE KATHERINE V8 FR.Inddpress 2

Pour votre information. Le communiqué de presse indispensable de L’Oréal Paris. LA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE INTERNATIONALE KATHERINE LANGFORD PRESS RELEASE_KATHERINE_V8_FR.indd 1 25/06/2020 3:29 PM Pour votre information. Le communiqué de presse indispensable de L’Oréal Paris. L’ORÉAL PARIS A L’IMMENSE “Nous sommes heureux d’accueillir Katherine dans la PLAISIR DE PRÉSENTER famille L’Oréal Paris. Elle est un modèle pour nous toutes, une jeune femme talentueuse et sûre d’elle qui utilise sa SA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE tribune pour une influence positive. L’étoile de Katherine ne fera que monter. En tant que jeune héroïne rayonnante INTERNATIONALE, qui encourage les gens à croire en eux-mêmes, elle est l’effigie parfaite pour incarner notre message de marque : KATHERINE LANGFORD. nous en valons tous la peine. ” Delphine Viguier-Hovasse ICÔNE MILLÉNAIRE Présidente de la marque mondiale L’Oréal Paris Audacieuse et sûre d’elle, Katherine Langford a déjà une grande influence sur sa génération. Cette actrice montante est, surtout, connue pour son rôle de ‘Hannah Baker’ dans la série 13 Reasons Why. Elle est également célèbre car elle a incarné, à l’écran, des jeunes femmes fortes. Aussi bien dans un rôle ou dans sa propre vie, elle s’est révélée battante s’exprimant pour RINE la tolérance et sensibilisant à l’égalité des sexes. Utilisant son LA NOUVELLE EFFIGIE INTERNATIONALE influence, elle a notamment encouragé les conversations en ligne sur le manque de confiance en soi, elle est déjà devenue un modèle inspirant pour beaucoup de femmes. À seulement 24 ans, elle incarne parfaitement les valeurs de L’Oréal Paris avec sa joie de vivre, son talent et ses convictions ; la marque est fière d’accueillir Katherine dans la famille. -

DEPRESSION AS REFLECTED on HANNAH BAKER in ASHER's THIRTEEN REASONS WHY Written By: Nur Idayu F041171524 THESIS Submitted to T

DEPRESSION AS REFLECTED ON HANNAH BAKER IN ASHER’S THIRTEEN REASONS WHY Written by: Nur Idayu F041171524 THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of Cultural Sciences Hasanuddin University in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements to Obtain Sarjana Degree in English Department ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF CULTURAL SCIENCES HASANUDDIN UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2021 i ii ii iii iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Firstly, the writer expressed gratitude to Allah SWT for His blessings that the writer can finally finished her thesis. This success, however, would not have been possible without the support, direction, counsel, assistance, and motivation of individuals in the writer‘s life. Therefore, the writer would like to thank: 1. The writer's family, especially to mother, father and brother who have supported and always prayed for the writer. Thank you for being patient and believing in the writer's dream. 2. Dr. M. Amir P., M.Hum., the writer's first thesis supervisors, who had provided her with excellent assistance throughout her academic years and had already inspired her to complete the Thesis by offering suggestions, comments, and corrections that had taught her a great deal. 3. Sitti Sahraeny, S.S., M.AppLing., the writer's second thesis advisors, for their compassion, advice, encouragement, comments, and knowledge in helping her better her writing. 4. All staff and lecturers of the English Literature Department at Hasanuddin University for their guidance and valuable lessons. 5. The writer‘s dearest and close friends. Thank you for the wonderful and unforgettable memories they have carved together with the writer. 6. Lastly, the writer also wants to appreciate herself for trying hard and not giving up. -

Cornell Alumni Magazine

c1-c4CAMja12_c1-c1CAMMA05 6/18/12 2:20 PM Page c1 July | August 2012 $6.00 Corne Alumni Magazine In his new book, Frank Rhodes says the planet will survive—but we may not Habitat for Humanity? cornellalumnimagazine.com c1-c4CAMja12_c1-c1CAMMA05 6/12/12 2:09 PM Page c2 01-01CAMja12toc_000-000CAMJF07currents 6/18/12 12:26 PM Page 1 July / August 2012 Volume 115 Number 1 In This Issue Corne Alumni Magazine 2 From David Skorton Generosity of spirit 4 The Big Picture Big Red return 6 Correspondence Technion, pro and con 5 10 10 From the Hill Graduation celebration 14 Sports Diamond jubilee 18 Authors Dear Diary 36 Wines of the Finger Lakes Hermann J. Wiemer 2010 Dry Riesling Reserve 52 Classifieds & Cornellians in Business 35 42 53 Alma Matters 56 Class Notes 38 Home Planet 93 Alumni Deaths FRANK H. T. RHODES 96 Cornelliana Who is Narby Krimsnatch? The Cornell president emeritus and geologist admits that the subject of his new book Legacies is “ridiculously comprehensive.” In Earth: A Tenant’s Manual, published in June by To see the Legacies listing for under - Cornell University Press, Rhodes offers a primer on the planet’s natural history, con- graduates who entered the University in fall templates the challenges facing it—both man-made and otherwise—and suggests pos- 2011, go to cornellalumnimagazine.com. sible “policies for sustenance.” As Rhodes writes: “It is not Earth’s sustainability that is in question. It is ours.” Currents 42 Money Matters BILL STERNBERG ’78 20 Teachable Moments First at the Treasury Department and now the White House, ILR grad Alan Krueger A “near-peer” year ’83 has been at the center of the Obama Administration’s response to the biggest finan- Flesh Is Weak cial crisis since the Great Depression. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Th1rteen R3asons Why Free

FREE TH1RTEEN R3ASONS WHY PDF Jay Asher | 288 pages | 06 May 2014 | RAZORBILL | 9781595141880 | English | New York, United States 13 Reasons Why (TV Series –) - IMDb Hannah seeks help from Mr. Porter, the school counselor. Clay plays the new tape for Tony and weighs what to do next. Clay and Hannah grow closer. While Clay spends a heartbreaking night listening to his tape with Tony, tensions boil over at Bryce's house. Hannah winds up Th1rteen R3asons Why a party after an argument with her parents. The students are served with subpoenas, and Justin wrestles with conflicting loyalties. Build up your Halloween Watchlist with our list of the most popular horror titles on Netflix in October. See the list. Th1rteen R3asons Why 13 Reasons Why — Watch the interview. Thirteen Reasons Why, based on the best-selling books by Jay Asher, follows teenager Clay Jensen Dylan Minnette as he returns home from school to find a mysterious box with his name on it lying on his porch. Inside he discovers a group of cassette tapes recorded by Hannah Baker Katherine Langford -his classmate and crush-who tragically committed suicide two Th1rteen R3asons Why earlier. On tape, Hannah unfolds an emotional audio diary, detailing the thirteen reasons why she decided to end her life. Through Hannah and Clay's dual narratives, Thirteen Reasons Why weaves an intricate and heartrending story of confusion and desperation that will deeply Th1rteen R3asons Why viewers. Written by Studio. Season one was great. If you've heard good things about this show, it's more than likely things being said about the first season. -

Seattle Queer Film Festival

10-20 OCTOBER 2019 seattlequeerfilm.org Isn’t it time you planned your financial future? Photo Credit: Sabel Roizen We are excited to welcome you to the 24th annual Translations: Seattle Transgender Film Festival, Reel Seattle Queer Film Festival! The latest in queer cinema Queer Youth, Three Dollar Bill Outdoor Cinema; special from across the globe is being celebrated right here membership screenings; and, of course, the Seattle in our neighborhood, with 157 films from 28 countries Queer Film Festival. We are able to do this vital work in screening over 11 days. the community thanks to the generous support of our This year, the festival showcases many new voices and members, donors, and patrons. experiences, with films from around the world and right SQFF24 carries through it a message of resistance and here in Seattle, including the Northwest premiere of representation, and reflects the LGBTQ2+ community on Argentina’s Brief Story from the Green Planet, winner of the screen. We are thrilled to share these stories with you. Berlin Film Festival’s Teddy Award; and the world premiere We hope you’ll feel a sense of connection and strength in of No Dominion: The Ian Horvath Story by local filmmaker numbers throughout your viewing experience. Plot your course with someone who understands your needs. and Pacific Northwest Ballet principal soloist Margaret We’ll see you at the movies! Mullin. We also feature programs that give you a chance Financial Advisor Steve Gunn, who has earned the Accredited Domestic to reflect on the last 50 years since the Stonewall Riots, SM SM Partnership Advisor and Chartered Retirement Planning Counselor with films like State of Pride by renowned filmmakers Rob designations, can help you develop a strategy for making informed Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, a 30th anniversary screening decisions about your financial future. -

The Suicide Motive of Hannah Baker in Jay Asher's 13 Reasons

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 491 Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Arts and Humanities (IJCAH 2020) The Suicide Motive of Hannah Baker in Jay Asher’s 13 Reasons Why Sesha Laras Andriani1,* Mamik Tri Wedawati1 1Faculty of Languages and Arts,Universitas Negeri Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Suicide has been one of the most significant issues in the world. Thus, this topic is very interesting to be discussed. The study aims to analyze the suicide motive of Hannah Baker. The study is focus on what the suicide motive of Hannah Baker is. The study applies descriptive qualitative methodology using the theory of needs by David McClelland to analyze the suicide motive of Hannah Baker. The result of the study reveals that Hannah Baker is lack of human needs fulfillment. Hannah cannot reach human needs like achievement needs, power needs, and affiliation needs. Those three aspects are supported by her personality. She is an introverted person who prefers to be alone and keep all her sadness within herself. In the end of the story, she tries to tell everything she feels to her counselling teacher, her teacher does not give the advice that she needs. It makes her feel helpless and worthless. She ends her life by cutting her wrist. Keywords: Motive, Suicide, Novel, Mental Health 1. INTRODUCTION Thus, person with this kind of personality should change the way of think, feel, and act. Person with this Suicide is an act of taking one’s own life. Each year, personality should think positively, feel the positive 800.000 people die by suicide and making it the second vibes, and act positively to decrease the possibility of main cause of death among the youth.