I ALUMNI IDENTITY: a STRUCTURAL EQUATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF with Citations

It Is Time For Congress To Take Action And Reform Our Nation’s Immigration Laws: A Plea From America’s Scholars May 1, 2013 The history of America is a history of immigration. Starting with our country’s founding by idealistic newcomers, the waves of immigrants who settled in the United States have continuously added to our culture and national identity. However, America’s immigration system has become out of step with the social and economic needs of our nation and, therefore, we believe policies must change. As university professors from across the United States, we believe that reforming our immigration laws is both the right thing to do and is in our nation’s best interests. As the community responsible for educating the next generation of Americans, we see the harm that a broken immigration system has had on our students and their families. For immigrant students who have studied and grown up in the U.S., we need to ensure that they have the opportunities to continue their education and settle into their careers in the U.S. Similarly, immigrants with credentials and skills already living in the U.S. should have the opportunity to practice their professions here. The positive effects that immigrant students have on our education system are manifold. Immigrant students contribute to the diversity of our classrooms, which in turn has a positive impact on all students. Diversity has been shown to be positively associated with students’ cognitive development, satisfaction with their educational experience, and leadership skills. We are educating these students in the U.S., but the broken immigration system makes it extremely difficult for students to stay and build a life in this country and for U.S. -

Raise the Minimum Wage He Minimum Wage Has Been an Important Part of Our Tnation’S Economy for 68 Years

Hundreds of Economists Say: Raise the Minimum Wage he minimum wage has been an important part of our Tnation’s economy for 68 years. It is based on the principle Hard work of valuing work by establishing an hourly wage floor beneath which employers cannot pay their workers. In so doing, the minimum wage helps to equalize the imbalance in bargaining deserves power that low-wage workers face in the labor market. The minimum wage is also an important tool in fighting poverty. fair pay The value of the 1997 increase in the federal minimum wage has been fully eroded. The real value of today’s federal minimum wage is less than it has been since 1951. Moreover, the ratio of the minimum wage to the average hourly wage of non-supervisory workers is 31%, its lowest level since World War II. This decline is causing hardship for low-wage workers and their families. We believe that a modest increase in the minimum wage would improve the well-being of low-wage workers and would not have the adverse effects that critics have claimed. In particular, we share the view the Council of Economic Advisors expressed in the 1999 Economic Report of the President that "the weight of the evidence suggests that modest increases in the minimum wage have had very little or no effect on employment." While controversy about the precise employment effects of the minimum wage continues, research has shown that most of the beneficiaries are adults, most are female, and the vast majority are members of low-income working families. -

N Guide.Indd

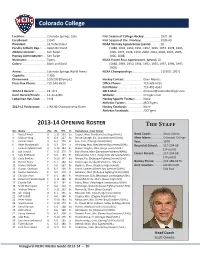

Colorado College Loca on:...........................Colorado Springs, Colo. First Season of College Hockey: ...................1937-38 Enrollment: ......................2,040 First Season of Div. I Hockey: .......................1939-40 President: .........................Jill Tiefenthaler NCAA Tourney Appearances (years): ...........20 Faculty Athle c Rep.: .......Ralph Bertrand (1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1955, 1957, 1978, 1995, Athle c Director: .............Ken Ralph 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, Hockey Administrator: .....Ken Ralph 2006, 2008) Nickname: ........................Tigers NCAA Frozen Four Appearances (years): 10 Colors: ..............................Black and Gold (1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1955, 1957, 1996, 1997, 2005) Arena: ...............................Colorado Springs World Arena NCAA Championships : ................................2 (1950, 1957) Capacity: ..........................7,380 Dimensions: .....................100x200 (Olympic) Hockey Contact: ......................Dave Moross Press Box Phone: .............719-540-6520 O ce Phone: .......................... 719-389-6755 Cell Phone: ..............................719-492-4347 2012-13 Record: ...............18-19-5 SID E-Mail: [email protected] Conf. Record/Finish: ........11-13-4/8th Website: ..................................CCTigers.com Le ermen Ret./Lost: . 1 9 / 8 Hockey Specifi c Twi er: ..........None Athle cs Twi er: .....................@CCTigers 2012-13 Postseason: ........L -

The Graduation Exercises Will Be Official

T HE GRADUA T ION EXE R C ISE S M OND AY, M AY THE SIXT EEN TH TWO THO U SAND AND E L EVEN N INE O’C LOCK IN THE MORNING T H OMAS K. HE ARN, JR. PLAZA THE CARILLON: “Nederlandse Volksliederen” ....................................................Dutch Folk Tune Lauren Rae Bradley (’05), University Carillonneur THE PROCESSIONAL ....................................................................e Brass Ensemble GREETINGS ......................................................................... Natalie E. Halpern (’11) Student Body President THE WELCOME ........................................................................... Nathan O. Hatch President THE PRAYER OF INVOCATION ..............................................e Reverend Timothy L. Auman University Chaplain THE ADDRESS: “For Humanity” ...............................................................Indra K. Nooyi Chairman and CEO, PepsiCo THE CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES ................................................. Jill Tiefenthaler Provost Rebecca S. Chopp, Doctor of Humane Letters Sponsor: Gail O’Day, Dean, School of Divinity Indra K. Nooyi, Doctor of Laws Sponsor: Steve Reinemund, Dean, Schools of Business William K. Suter, Doctor of Laws Sponsor: Blake Morant, Dean, School of Law Andrew C. von Eschenbach, Doctor of Science Sponsor: Lorna Moore, Dean, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences REMARKS TO THE GRADUATES ............................................................President Hatch THE HONORING OF RETIRING FACULTY FROM THE BOWMAN GRAY CAMPUS David A. Albertson, -

2019 ECOC Summit Program.Pub

1 ECOC 2019 Summit Locations & Directions jkop W1 E. Uintah Street Special Notes *Parking on campus is by permit. However, it will not be enforced on ECOC Summit day. *To reach elevator in Barnes, follow Sign down hall to left. *Cossitt Gym is down steps immediately Barnes ahead inside entrance. To reach elevator in Cossitt, follow Palmer Hall signs down hall ahead, then to right. *In Palmer & Cornerstone, to reach the North 2ndfloor, push #3 in elevator. Cascade Olin Bemis *Sidewalks/ Accessible Routes North *Steep walkway Cutler Nevada *Campus Guides indicated by Cossitt *Entrance to Olin 1 - El Pomar & Make hard right I Worner Armstrong Reid Arena I Around corner. W. Cache La Poudre E. Cache La Poudre *Accessible building Entrances. Cornerstone I *Information Desks indicated by: I *Note: all parking lots have accessible parking, except the westernmost Lot. *Colorado College is a smoke/tobacco- free campus. Welcome: The Board of Directors welcomes you to our flagship program, the 12th Annual Educang Children of Color (ECOC) Summit: Building Bridges Mission: To dismantle the cradle to prison pipeline for children of color and children in poverty, through educaon. What We Do: ECOC, Inc., provides five programs: The Educang Children of Color Summit provides a unique opportunity for educators, juvenile jusce, and child welfare professionals to enhance their ability to retain and inspire the students they serve. It is also an opportunity for high school students to learn about themselves while they explore higher educaon. Finally, the Summit is an opportunity for parents to learn to communicate with schools and with their children to maximize their child’s success. -

New Colorado College President Named

For Immediate Release Contact: Leslie Weddell (719) 389-6038 [email protected] L. SONG RICHARDSON APPOINTED 14th PRESIDENT OF COLORADO COLLEGE UC Irvine School of Law dean assumes role on July 1 COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. – Dec. 9, 2020 – The Colorado College Board of Trustees today appointed L. Song Richardson the 14th president of Colorado College following a unanimous vote. Richardson, currently the dean and chancellor’s professor of law at University of California Irvine School of Law, will succeed President Jill Tiefenthaler, who led CC for nine years. Richardson is a legal scholar and lawyer whose research focuses on implicit racial and gender bias. She became UC Irvine School of Law’s dean and chancellor’s professor of law in January 2018, and at that time was the only woman of color to lead a top-30 law school. Her presidency at Colorado College will begin on July 1, 2021. “Dean Richardson embodies the curiosity, dedication, spirit, commitment and joy that are the essence of CC,” said Susie Burghart, chair of the board of trustees and a 1977 Colorado College graduate. “She is authentic and accessible, a scholar committed to building the resiliency, depth and breadth of students, and a changemaker who will shift CC and our future graduates forward on the path toward antiracism, access and even greater academic excellence.” Richardson said she was drawn to Colorado College because of its people, its sense of purpose, and its commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion, increasing access for students, sustainability and innovation. “I never dreamed that I would be leaving UCI Law, a community that I adore and a school that has achieved unprecedented success in less than 11 years of existence,” Richardson said. -

Tiger Hockey 2012-13 Media Guide

2012-13 SCHEDULE Home games in BOLD CAPS All times local SUN., OCT. 7 UNIV. OF BRITISH COLUMBIA 6:07 PM SAT.-SUN, OCT. 12/13 CLARKSON UNIV. 7:37/7:07 PM Fri., Oct. 19 @ Air Force Academy 7 pm SAT., OCT. 20 UMASS-LOWELL 7:07 PM Fri.,-Sat., Oct. 26/27 @ Cornell University 5/5 pm Fri.-Sat., Nov. 2//3 @ Univ. of Wisconsin 6:07/6:07 pm FRI.,-SAT., NOV. 9/10 BEMIDJI STATE UNIV. 7:37/7:07 PM FRI.,-NOV. 16 UNIV. OF DENVER 7:37 PM Sat., Nov. 17 @ Univ. of Denver 7:07 pm FRI., NOV. 23 UNIV. OF NEW HAMPSHIRE 7:37 PM SAT., NOV. 24 YALE UNIV. 7:37 PM FRI., NOV. 30 UNIV. OF NORTH DAKOTA 7:37 PM SAT., DEC. 1 UNIV. OF NORTH DAKOTA 7:07 PM FRI.,-SAT.,, DEC. 7/8 UNIV. OF MINNESOTA 7:37/7:07 PM Fri.,-Sat., Dec. 14/15 @ St. Cloud State State Univ. 6:37/6:07 pm Fri.,-Sat., Jan. 4/5 @ Univ. of Nebraska Omaha 6:37/6:07 pm Fri.,-Sat., Jan. 11/12 @ Univ. of North Dakota 6:37/6:07 pm FRI.,-SAT., JAN. 18-19 UNIV. OF MINNESOTA DULUTH 7:37/7:07 PM Fri.,-Sat., Feb. 1-2 @ Univ. of Alaska Anchorage 9:07/9:07 pm Fri., Feb. 8 @ Univ. of Denver 7:37 pm SAT., FEB. 9 UNIV. OF DENVER 7:07 PM FRI.,-SAT., FEB. 22/23 ST. CLOUD STATE UNIV. 7:37/7:07 PM FRI.,-SAT., MAR. -

June 4, 2020 Donald J. Trump President of the United States the White House 1600

June 4, 2020 Steering Committee Louis Caldera Co-Chair and Senior Advisor Donald J. Trump Nancy Cantor President of the United States Co-Chair Chancellor The White House Rutgers University – Newark 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. NW David W. Oxtoby Washington, DC 20500 Co-Chair President Emeritus Pomona College Re: Alliance of 450+ University and College Presidents and Chancellors President American Academy of Arts and Supports Continued Existence of Optional Practical Training (OPT) Sciences Noelle E. Cockett President Dear President Trump: Utah State University Alan W. Cramb On behalf of the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration President Illinois Institute of Technology (Presidents’ Alliance), we write to express our unqualified support for Optional Practical Training (OPT), and STEM OPT and respectfully urge you not to issue an José Luis Cruz Executive Vice Chancellor Executive Order or Presidential Proclamation to, or otherwise direct the U.S. University Provost City University of New York Department of Homeland Security (DHS) or its component agencies to issue regulations or policy guidance that would suspend, end, or reduce the availability John J. DeGioia President of these programs. Indefinitely or temporarily suspending OPT would substantially Georgetown University undermine our nation’s economic recovery while dismantling our nation’s ability to Mark Erickson competitively attract and retain top international student and scholar talent. President Northampton Community College The non-partisan Presidents’ Alliance comprises over 450 college and university Jane Fernandes President presidents and chancellors of public and private institutions. We represent all Guilford College sectors of higher education. Together, our members’ institutions enroll over five Kent Ingle million students across 41 states, D.C., and Puerto Rico. -

NEWSLETTER Vanderbilt University Nashville

Amevican Econorrnic Association 1994 Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession REBECCA M. BLANK (Chatr) Department of Economics Northwestern Uniwrsily 2040 Sheridan Road Evartrton. IL 60208 . 708 1 491-4145: FAX 708 1467-2459 KATHRYN H. ANDERSON Dep;mment of Economics Box 11. Station B NEWSLETTER Vanderbilt University Nashville. TN 37235 615 1322-3425 Winter Issue February 1994 ROBIN L. BARTLETT Department of Economics Denison University Granville. OH 43023 Rebecca Blank, Co-Editor Ivy Broder, Co-Edi tor 614 / 587-6574 (708149 1-4 145) (2021885-2125) IVY BRODER . Dcpartment of Economics The Amcrican University Washington. D.C. 2M)16. 202 1885-215 Helen Goldblatt, Asst. Editor LINDA EDWARDS Depanmcnt uf Economics (708149 1-4 145) Queens College of CUNY Flushing. NY 11367 718 1997.5464 ROSALD G. EHRENBERG New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations IN THIS ISSUE: Ctanell University Ithaca. NY 14853 607 / 255-3026 1993 Annual Report ... 2 10 ANNA GRAY Depsrtnent of Econoniics . Walls Are Falling for Women in Economics, but Slowly ... 8 Univenity of Oregon Eugene. OR 97403 Guidelines for Being a Discussant . .10 503 1346-1266 Professional Life Beyond Academe -- Yes, There Is One ... 11 JON1 HERSCH Department of Economics :and Finance CSWEP at the 1994 Eastern Economic Association Meeting . .12 University of Wyoming Lamrnie. WY 82071 307 1766-2358 Biographical Sketches of CSWEP Board Members ... 13 IRENE LURlE Demment of Public Administralion & Policy. Milne.103 SUNY-Albany Summary of the 1993 CSWEP-Organized Sessions Albany. NY 12222 at the SEA Meeting . .14 51s 1442-527.0 NANCY MARION Dcpanment of ~conomics Summaries of CSWEP-Organized Sessions Dartmouth College Hanover. -

A Year of Listening: Exploring New Heights at Colorado College

A Year of Listening Exploring New Heights at Colorado College By Jill Tiefenthaler, President When I arrived at Colorado College last summer, many people asked what drew me here. I explained that the unique combination of strength and ambition, along with a sense of adventure, was irresistible! Over the course of my first year, many experiences have underscored that first impression. Of course, great new colleagues and warm friendships have only added to the intense attachment I feel for this wonderful place. We are indeed a college of immense strengths. Our students are truly remarkable. Their confidence, curiosity, innovative spirit, and talent inspire awe and appreciation for all they offer while they are in our midst — and later as alumni who continue to give back to this community. Our faculty members are absolutely committed to undergraduate education both inside and outside of the classroom; they display their wide-ranging pedagogical and research skills in their mastery of the Block Plan. We have dedicated staff members and coaches who are inspired by our mission and who show their commitment to both our students and community in ways large and small. Bold action is part of our history. We were one of the first liberal arts colleges in the West, and we developed our distinctive Block Plan in 1970. Our entrepreneurial and innovative spirit continues to permeate today through creative team-taught courses, student endeavors like Venture Grants, blocks abroad, and block breaks. These learning experiences set our alumni apart as independent-minded leaders in their fields. Another strength is our financial condition. -

CC-GRAD-Classof2021-Program.Pdf

147th academic year CLASS OF 2021 Sunday, May 23, 2021 9 a.m. Weidner Field Colorado Springs, Colorado SENIOR CLASS GIFT The Class of 2021 demonstrated their commitment to Colorado College through their philanthropic senior class gift effort. They have directed gifts toward the Colorado College Mutual Aid Fund—a fund created by students to support immediate needs facing their classmates such as housing and food insecurity. LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Colorado College is located within the unceded territory of the Ute Peoples. Other tribes who historically used, and continue to use, the land also include the Apache, Arapaho, Comanche, and Cheyenne. IMPORTANT INFORMATION Sign Language Interpretation: Guests who are deaf or hard of hearing may sit on the west side of the field (section 104) where the stadium screen is visible. Photography: A professional photographer will be taking photos of each graduate. To order your photos please visit www.gradimages.com. Audience members for today’s event may be filmed, recorded, or photographed. Visitors consent to appear in documentation and media and its future use by Colorado College. Gown Returns: Graduates may keep their gowns or recycle them in bins located near the exit. Recording Available Online: The Commencement video recording will be available for viewing beginning June 15 at www.coloradocollege.edu/commencement . Share your photos and tweets: #coloradocollege2021 www.coloradocollege.edu/commencement – 2 – Dear Class of 2021, We are excited to be together today to mark this important milestone: your graduation. Whether in person or virtual, you spent four years living and learning in a fast-paced living and learning community and brought meaning to your studies through dynamic curricular engagements. -

Colorado College Tigers

Colorado College Tigers Quick Facts 2014-15 Schedule Date Opponent Time (MT) Location (Pop.): .......Colorado Springs, Colo. (446,439) Sun., Oct. 5 McGill (Exh.) 6:07 p.m. Fri., Oct. 10 Alabama-Huntsville 7:37 p.m. Founded: ............................................................... 1874 Sat., Oct. 11 Alabama-Huntsville 7:07 p.m. Enrollment: ........................................................... 2,034 Fri., Oct. 17 North Dakota* 7:37 p.m. Nickname:............................................................ Tigers Sat., Oct. 18 North Dakota* 7:07 p.m. Colors: ...................................................Black and Gold Fri., Oct. 24 at Boston College 5:30 p.m. President: .............................................. Jill Tiefenthaler Sat., Oct. 25 at New Hampshire 5 p.m. Fri., Nov. 7 at Miami* 5:35 p.m. Director of Athletics:.......................................Ken Ralph Sat., Nov. 8 at Miami* 5:05 p.m. Hockey Admin.:..............................................Ken Ralph Fri., Nov. 14 at Denver* 7:37 p.m. Faculty Athletic Rep.: ............................Pedro de Araujo Fri., Nov. 21 Wisconsin 7:37 p.m. Athletic Dept. Phone #: ..........................(719) 389-6475 Sat., Nov. 22 at Air Force 7:05 p.m. Fri., Dec. 5 at Minnesota Duluth* 6:07 p.m. SEASON IN REVIEW Sat., Dec. 6 at Minnesota Duluth* 6:07 p.m. 2013-14 Overall Record: .....................................7-24-6 Fri., Dec. 12 at Western Michigan* 5 p.m. 2013-14 NCHC Record/Finish: ...................6-13-5-1/7th Sat., Dec. 13 at Western Michigan* 5 p.m. 2014 NCHC Tournament Record: ............................. 1-2 Sat., Dec. 27 U.S. U-18 Team (Exh.) 7:37 p.m. 2014 NCHC Tournament Finish: ................Quarterfinals Sun., Dec. 28 U.S. U-18 Team (Exh.) 7:07 p.m. Sat., Jan.