Liberal Education Winter-Spring 2020. Democracy in Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IS DEMOCRACY in TROUBLE? According to Many Scholars, Modern Liberal Democracy Has Advanced in Waves

IS DEMOCRACY IN TROUBLE? According to many scholars, modern liberal democracy has advanced in waves. But liberal democracy has also had its set- backs. Some argue that it is in trouble in the world today, and that the young millennial generation is losing faith in it. FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2017 Source: Freedom in the World 2017 This map was prepared by Freedom House, an independent organization that monitors and advocates for democratic government around the globe. According to this map, how free is your country? Which areas of the world appear to be the most free? Which appear to be the least free? (Freedom House) Since the American and French revolutions, there authoritarian leaders like Russia’s Vladimir Putin. have been three major waves of liberal democracies. Freedom House has rated countries “free,” “partly After each of the first two waves, authoritarian regimes free,” and “not free” for more than 70 years. Its Free- like those of Mussolini and Hitler arose. dom in the World report for 2016 identified 67 coun- A third wave of democracy began in the world in the tries with net declines in democratic rights and civil mid-1970s. It speeded up when the Soviet Union and the liberties. Only 36 countries had made gains. This nations it controlled in Eastern Europe collapsed. Liberal marked the 11th straight year that declines outnum- democracies were 25 percent of the world’s countries in bered gains in this category. 1975 but surged to 45 percent in 2000. The big news in the Freedom House report was that Many believed liberal democracy was on a perma- “free” countries (i.e., liberal democracies) dominated the nent upward trend. -

The Two Faces of Populism: Between Authoritarian and Democratic Populism

German Law Journal (2019), 20, pp. 390–400 doi:10.1017/glj.2019.20 ARTICLE The two faces of populism: Between authoritarian and democratic populism Bojan Bugaric* (Received 18 February 2019; accepted 20 February 2019) Abstract Populism is Janus-faced; simultaneously facing different directions. There is not a single form of populism, but rather a variety of different forms, each with profoundly different political consequences. Despite the current hegemony of authoritarian populism, a much different sort of populism is also possible: Democratic and anti-establishment populism, which combines elements of liberal and democratic convic- tions. Without understanding the political economy of the populist revolt, it is difficult to understand the true roots of populism, and consequently, to devise an appropriate democratic alternative to populism. Keywords: authoritarian populism; democratic populism; Karl Polanyi; political economy of populism A. Introduction There is a tendency in current constitutional thinking to reduce populism to a single set of universal elements. These theories juxtapose populism with constitutionalism and argue that pop- ulism is by definition antithetical to constitutionalism.1 Populism, according to this view, under- mines the very substance of constitutional (liberal) democracy. By attacking the core elements of constitutional democracy, such as independent courts, free media, civil rights and fair electoral rules, populism by necessity degenerates into one or another form of non-democratic and authori- tarian order. In this article, I argue that such an approach is not only historically inaccurate but also norma- tively flawed. There are historical examples of different forms of populism, like the New Deal in the US, which did not degenerate into authoritarianism and which actually helped the American democracy to survive the Big Depression of the 1930s. -

Technological Revolution, Democratic Recession and Climate Change: the Limits of Law in a Changing World

TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION, DEMOCRATIC RECESSION AND CLIMATE CHANGE: THE LIMITS OF LAW IN A CHANGING WORLD Luís Roberto Barroso Senior Fellow, Carr Center for Human Rights Policy Justice, Brazilian Supreme Court CARR CENTER DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Discussion Paper 2019-009 For Academic Citation: Luís Roberto Barroso. Technological Revolution, Democratic Recession and Climate Change: The Limits of Law in a Changing World. CCDP 2019-009. September 2019. The views expressed in Carr Center Discussion Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Harvard Kennedy School or of Harvard University. Discussion Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Technological Revolution, Democratic Recession and Climate Change: The Limits of Law in a Changing World About the Author Luís Roberto Barroso is a Senior Fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. He is a Justice at the Brazilian Supreme Court and a Law Professor at Rio de Janeiro State University. He holds a Master’s degree in Law from Yale Law School (LLM), and a Doctor’s degree (SJD) from the Rio de Janeiro State University. He was a Visiting Scholar at Harvard Law School in 2011 and has been Visiting Professor at different universities in Brazil and other countries. Carr Center for Human Rights Policy Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.carrcenter.hks.harvard.edu Copyright 2019 Discussion Paper September 2019 Table of Contents TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION, DEMOCRATIC RECESSION AND CLIMATE CHANGE: THE LIMITS OF LAW IN A CHANGING WORLD ..................................................................................................................................... -

Living Our Democratic Values

Living Our Democratic Values Protecting human rights and upholding democratic values has been a perennial goal for presidents of both major political parties in the United States. Yet the current administration has abandoned our democratic allies and values by embracing authoritarian leaders, enabling corruption, and engaging in a transactional foreign policy. The next administration must take immediate steps to reverse harmful policies and halt human rights violations in U.S. domestic and foreign policy, demonstrating through words and deeds a renewed commitment to living our values. ›› 31 Center for American Progress | The First 100 Days: Living Our Democratic Values Over successive administrations, the United States has strived—however imperfectly— to uphold democratic values. Yet the current administration has actively undermined those values, damaging America’s democratic institutions and attacking the very idea of universal human rights.1 President Donald Trump has coddled dictators and repudi- ated America’s most reliable treaty allies.2 In the process, his administration has hobbled America’s ability to pursue its founding principles at home and abroad. Rebuilding America’s support for democracy and respect for human rights will take serious time and energy, and the next administration must get started immediately in January 2021. The damage that the next administration will need to repair is immense. It is hard to overestimate the harm that the current administration has inflicted. From daily attacks on the free press3 to intervening in Justice Department investigations4 to using the Oval Office to promote private business interests,5 the Trump administration has assaulted fundamental norms that American presidents and leaders have long upheld. -

Pitchfork Politics Elections

failed to gain traction in national THE AME Pitchfork Politics elections. On the left, the countercultural protest movements of the 1960s and The Populist Threat to 1970s challenged the status quo but didn’t secure institutional representa- R I Liberal Democracy tion until their radicalism had subsided. C As the political scientists Seymour AN DISTEMPER Yascha Mounk Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan famously observed, during the postwar years, the party structures of North America and ince Roman times, virtually every western Europe were “frozen” to an type of government that holds unprecedented degree. Between 1960 Scompetitive elections has experi- and 1990, the parties represented in the enced some form of populism—some parliaments of Amsterdam, Copenhagen, attempt by ambitious politicians to Ottawa, Paris, Rome, Stockholm, Vienna, mobilize the masses in opposition to an and Washington barely changed. For a establishment they depict as corrupt or few decades, Western political establish- self-serving. From Tiberius Gracchus and ments held such a firm grip on power the populares of the Roman Senate, to the that most observers stopped noticing champions of the popolo in Machiavelli’s just how remarkable that stability was sixteenth-century Florence, to the Jacobins compared to the historical norm. in Paris in the late eighteenth century, Yet beginning in the 1990s, a new to the Jacksonian Democrats who stormed crop of populists began a steady rise. nineteenth-century Washington—all Over the past two decades, populist based their attempts at mass mobilization movements in Europe and the United on appeals to the simplicity and goodness States have uprooted traditional party of ordinary people. -

2016-2017 Report

The Society of Fellows in the Humanities Annual Report 2016–2017 Society of Fellows Mail Code 5700 Columbia University 2960 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Phone: (212) 854-8443 Fax: (212) 662-7289 [email protected] www.societyoffellows.columbia.edu By FedEx or UPS: Society of Fellows 74 Morningside Drive Heyman Center, First Floor East Campus Residential Center Columbia University New York, NY 10027 Posters courtesy of designers Amelia Saul and Sean Boggs 2 Contents Report From The Chair 5 Special Events 31 Members of the 2016–2017 Governing Board 8 Heyman Center Events 35 • Event Highlights 36 Forty-Second Annual Fellowship Competition 9 • Public Humanities Initiative 47 Fellows in Residence 2016–2017 11 • Heyman Center Series and Workshops 50 • Benjamin Breen 12 Nietzsche 13/13 Seminar 50 • Christopher M. Florio 13 New Books in the Arts & Sciences 50 • David Gutkin 14 New Books in the Society of Fellows 54 • Heidi Hausse 15 The Program in World Philology 56 • Arden Hegele 16 • Full List of Heyman Center Events • Whitney Laemmli 17 2016–2017 57 • Max Mishler 18 • María González Pendás 19 Heyman Center Fellows 2016–2017 65 • Carmel Raz 20 Alumni Fellows News 71 Thursday Lectures Series 21 Alumni Fellows Directory 74 • Fall 2016: Fellows’ Talks 23 • Spring 2017: Shock and Reverberation 26 2016–2017 Fellows at the annual year-end Spring gathering (from left): María González Pendás (2016–2019), Arden Hegele (2016–2019), David Gutkin (2015–2017), Whitney Laemmli (2016–2019), Christopher Florio (2016–2019) Heidi Hausse (2016–2018), Max Mishler (2016–2017), and Carmel Raz (2015–2018). -

Unai Members List August 2021

UNAI MEMBER LIST Updated 27 August 2021 COUNTRY NAME OF SCHOOL REGION Afghanistan Kateb University Asia and the Pacific Afghanistan Spinghar University Asia and the Pacific Albania Academy of Arts Europe and CIS Albania Epoka University Europe and CIS Albania Polytechnic University of Tirana Europe and CIS Algeria Centre Universitaire d'El Tarf Arab States Algeria Université 8 Mai 1945 Guelma Arab States Algeria Université Ferhat Abbas Arab States Algeria University of Mohamed Boudiaf M’Sila Arab States Antigua and Barbuda American University of Antigua College of Medicine Americas Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Facultad Regional Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Universidad Abierta Interamericana Americas Argentina Universidad Argentina de la Empresa Americas Argentina Universidad Católica de Salta Americas Argentina Universidad de Congreso Americas Argentina Universidad de La Punta Americas Argentina Universidad del CEMA Americas Argentina Universidad del Salvador Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cordoba Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de la Pampa Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Rosario Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de -

Download PDF with Citations

It Is Time For Congress To Take Action And Reform Our Nation’s Immigration Laws: A Plea From America’s Scholars May 1, 2013 The history of America is a history of immigration. Starting with our country’s founding by idealistic newcomers, the waves of immigrants who settled in the United States have continuously added to our culture and national identity. However, America’s immigration system has become out of step with the social and economic needs of our nation and, therefore, we believe policies must change. As university professors from across the United States, we believe that reforming our immigration laws is both the right thing to do and is in our nation’s best interests. As the community responsible for educating the next generation of Americans, we see the harm that a broken immigration system has had on our students and their families. For immigrant students who have studied and grown up in the U.S., we need to ensure that they have the opportunities to continue their education and settle into their careers in the U.S. Similarly, immigrants with credentials and skills already living in the U.S. should have the opportunity to practice their professions here. The positive effects that immigrant students have on our education system are manifold. Immigrant students contribute to the diversity of our classrooms, which in turn has a positive impact on all students. Diversity has been shown to be positively associated with students’ cognitive development, satisfaction with their educational experience, and leadership skills. We are educating these students in the U.S., but the broken immigration system makes it extremely difficult for students to stay and build a life in this country and for U.S. -

Raise the Minimum Wage He Minimum Wage Has Been an Important Part of Our Tnation’S Economy for 68 Years

Hundreds of Economists Say: Raise the Minimum Wage he minimum wage has been an important part of our Tnation’s economy for 68 years. It is based on the principle Hard work of valuing work by establishing an hourly wage floor beneath which employers cannot pay their workers. In so doing, the minimum wage helps to equalize the imbalance in bargaining deserves power that low-wage workers face in the labor market. The minimum wage is also an important tool in fighting poverty. fair pay The value of the 1997 increase in the federal minimum wage has been fully eroded. The real value of today’s federal minimum wage is less than it has been since 1951. Moreover, the ratio of the minimum wage to the average hourly wage of non-supervisory workers is 31%, its lowest level since World War II. This decline is causing hardship for low-wage workers and their families. We believe that a modest increase in the minimum wage would improve the well-being of low-wage workers and would not have the adverse effects that critics have claimed. In particular, we share the view the Council of Economic Advisors expressed in the 1999 Economic Report of the President that "the weight of the evidence suggests that modest increases in the minimum wage have had very little or no effect on employment." While controversy about the precise employment effects of the minimum wage continues, research has shown that most of the beneficiaries are adults, most are female, and the vast majority are members of low-income working families. -

Undergraduate Catalogue 2016–2017

UNDERGRADUATE CATALOGUE 2016–2017 Effat College of Science and Humanities Effat College of Engineering Effat College of Business Effat College of Architecture and Design BOARD OF TRUSTEES HRH Princess Sarah Al Faisal HH Prince Bandar Bin Dr Saad Bin Saud Al Fehaid Chairman of Effat University Saud Bin Khalid Al Saud Ministry of Education Representative Board of Trustees Member of Effat University Board on Effat University Board of Trustees of Founders and Board of Trustees HRH Prince Mohammed Al Faisal Ministry Deputy of Private Education Member of Effat University Secretary General, and General Supervisor of Private Board of Trustees King Faisal Foundation Higher Education HRH Princess Latifah Al Faisal Member of Al Faisal University Dr Abdul Aziz M. Al Abdul Jabbar Member of Effat University Board of Trustees, and Chairman Member of Effat University Board of Trustees of the Executive Committee Board of Trustees HRH Prince Khalid Al Faisal HRH Princess Haifa Professor, Dept. of Special Education, Member of Effat University Bint Saud Al Faisal College of Education, King Saud Board of Trustees Member of Effat University University, Riyadh Board of Trustees Advisor to the Custodian of the Two Holy Dr Mohammed Bin Mosques and Governor of Makkah Region HRH Prince Saud Bin Ahmed Al Wadaan Abdul Rahman Al Faisal Member of Effat University Chief Executive Offi cer (CEO), Member of Effat University Board of Trustees King Faisal Foundation Board of Trustees King Saud University, Riyadh HRH Prince Saud Al Faisal HRH Princess Noura Member of Effat University Dr Omar Abdullah Al Swailem Bint Turki Al Faisal Board of Trustees Member of Effat University Member of Effat University Board of Trustees HRH Prince Turki Al Faisal Board of Trustees Chairman, Board of Directors, King Faisal Dean of the College of Engineering Assistant to the Vice Chairman Center for Research and Islamic Studies Sciences, King Fahd University of of the Board of Trustees Petroleum & Minerals, Dhahran Member of Effat University HRH Prince Sultan Board of Trustees Prof. -

N Guide.Indd

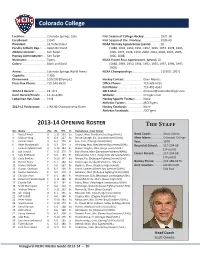

Colorado College Loca on:...........................Colorado Springs, Colo. First Season of College Hockey: ...................1937-38 Enrollment: ......................2,040 First Season of Div. I Hockey: .......................1939-40 President: .........................Jill Tiefenthaler NCAA Tourney Appearances (years): ...........20 Faculty Athle c Rep.: .......Ralph Bertrand (1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1955, 1957, 1978, 1995, Athle c Director: .............Ken Ralph 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, Hockey Administrator: .....Ken Ralph 2006, 2008) Nickname: ........................Tigers NCAA Frozen Four Appearances (years): 10 Colors: ..............................Black and Gold (1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1955, 1957, 1996, 1997, 2005) Arena: ...............................Colorado Springs World Arena NCAA Championships : ................................2 (1950, 1957) Capacity: ..........................7,380 Dimensions: .....................100x200 (Olympic) Hockey Contact: ......................Dave Moross Press Box Phone: .............719-540-6520 O ce Phone: .......................... 719-389-6755 Cell Phone: ..............................719-492-4347 2012-13 Record: ...............18-19-5 SID E-Mail: [email protected] Conf. Record/Finish: ........11-13-4/8th Website: ..................................CCTigers.com Le ermen Ret./Lost: . 1 9 / 8 Hockey Specifi c Twi er: ..........None Athle cs Twi er: .....................@CCTigers 2012-13 Postseason: ........L -

Educating Saudi Women an Interview with Haifa Jamal Al-Lail, President of Efat University, a Women’S University in Saudi Arabia

voices BY ELAINA LOVELAND Educating Saudi Women An interview with Haifa Jamal Al-Lail, president of Efat University, a women’s university in Saudi Arabia HAIFA JAMAL AL-LAIL, a native of Saudi Arabia, joined Effat University in 1998 and began her tenure as presi- dent in May 2008. She was named one of 1000 Women for the Nobel Peace Prize 2005 and is the winner of the Distinguished Arab Woman Award in 2005. A respected author and researcher, she is well known for her exper- tise in privatization and empowerment of women. She is the author of a number of articles and has developed and taught undergraduate and graduate courses on topics such as public administration and public policy. Before joining Effat University, Al-Lail was the first dean of girls’ campus in King Abdulaziz University. She was a visiting scholar at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University in 2001. She partici- pated in the Summer Institute for Women in Higher Education Administration at Bryn Mawr College in 2000. She received a PhD in public policy from the University of Southern California (USC). IE: Can you describe Efat University and how you became its IE: How has Efat University grown since it was first president? established? HAIFA JAMAL AL-LAIL: Effat University is a private nonprofit HAIFA JAMAL AL-LAIL: We began from those two departments institution in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It started in 1999 with and it was a college at that time in 1999, until 2009, then we became the vision of Queen Effat, the wife of the late King Faisal.