Stellar Evolution Variable Stars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Exoplanet Populations with NASA's Kepler Mission

SPECIAL FEATURE: PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE SPECIAL FEATURE: Exploring exoplanet populations with NASA’s Kepler Mission Natalie M. Batalha1 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, 94035 CA Edited by Adam S. Burrows, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and accepted by the Editorial Board June 3, 2014 (received for review January 15, 2014) The Kepler Mission is exploring the diversity of planets and planetary systems. Its legacy will be a catalog of discoveries sufficient for computing planet occurrence rates as a function of size, orbital period, star type, and insolation flux.The mission has made significant progress toward achieving that goal. Over 3,500 transiting exoplanets have been identified from the analysis of the first 3 y of data, 100 planets of which are in the habitable zone. The catalog has a high reliability rate (85–90% averaged over the period/radius plane), which is improving as follow-up observations continue. Dynamical (e.g., velocimetry and transit timing) and statistical methods have confirmed and characterized hundreds of planets over a large range of sizes and compositions for both single- and multiple-star systems. Population studies suggest that planets abound in our galaxy and that small planets are particularly frequent. Here, I report on the progress Kepler has made measuring the prevalence of exoplanets orbiting within one astronomical unit of their host stars in support of the National Aeronautics and Space Admin- istration’s long-term goal of finding habitable environments beyond the solar system. planet detection | transit photometry Searching for evidence of life beyond Earth is the Sun would produce an 84-ppm signal Translating Kepler’s discovery catalog into one of the primary goals of science agencies lasting ∼13 h. -

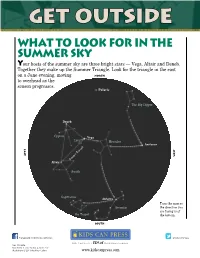

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your Hosts of the Summer Sky Are Three Bright Stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your hosts of the summer sky are three bright stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb. Together they make up the Summer Triangle. Look for the triangle in the east on a June evening, moving NORTH to overhead as the season progresses. Polaris The Big Dipper Deneb Cygnus Vega Lyra Hercules Arcturus EaST West Summer Triangle Altair Aquila Sagittarius Antares Turn the map so Scorpius the direction you are facing is at the Teapot the bottom. south facebook.com/KidsCanBooks @KidsCanPress GET OUTSIDE Text © 2013 Jane Drake & Ann Love Illustrations © 2013 Heather Collins www.kidscanpress.com Get Outside Vega The Keystone The brightest star in the Between Vega and Arcturus, Summer Triangle, Vega is look for four stars in a wedge or The summer bluish white. It is in the keystone shape. This is the body solstice constellation Lyra, the Harp. of Hercules, the Strongman. His feet are to the north and Every day from late Altair his arms to the south, making December to June, the The second-brightest star in his figure kneel Sun rises and sets a little the triangle, Altair is white. upside down farther north along the Altair is in the constellation in the sky. horizon. But about June Aquila, the Eagle. 21, the Sun seems to stop Keystone moving north. It rises in Deneb the northeast and sets in The dimmest star of the the northwest, seemingly Summer Triangle, Deneb would in the same spots for be the brightest if it were not so Hercules several days. -

Summer Constellations

Night Sky 101: Summer Constellations The Summer Triangle Photo Credit: Smoky Mountain Astronomical Society The Summer Triangle is made up of three bright stars—Altair, in the constellation Aquila (the eagle), Deneb in Cygnus (the swan), and Vega Lyra (the lyre, or harp). Also called “The Northern Cross” or “The Backbone of the Milky Way,” Cygnus is a horizontal cross of five bright stars. In very dark skies, Cygnus helps viewers find the Milky Way. Albireo, the last star in Cygnus’s tail, is actually made up of two stars (a binary star). The separate stars can be seen with a 30 power telescope. The Ring Nebula, part of the constellation Lyra, can also be seen with this magnification. In Japanese mythology, Vega, the celestial princess and goddess, fell in love Altair. Her father did not approve of Altair, since he was a mortal. They were forbidden from seeing each other. The two lovers were placed in the sky, where they were separated by the Celestial River, repre- sented by the Milky Way. According to the legend, once a year, a bridge of magpies form, rep- resented by Cygnus, to reunite the lovers. Photo credit: Unknown Scorpius Also called Scorpio, Scorpius is one of the 12 Zodiac constellations, which are used in reading horoscopes. Scorpius represents those born during October 23 to November 21. Scorpio is easy to spot in the summer sky. It is made up of a long string bright stars, which are visible in most lights, especially Antares, because of its distinctly red color. Antares is about 850 times bigger than our sun and is a red giant. -

Unknown Amorphous Carbon II. LRS SPECTRA the Sample Consists Of

Table I A summary of the spectral -features observed in the LRS spectra of the three groups o-f carbon stars. The de-finition o-f the groups is given in the text. wavelength Xmax identification Group I B - 12 urn E1 9.7 M™ Silicate 12 - 23 jim E IB ^m Silicate Group II < 8.5 M"i A C2H2 CS? 12 - 16 f-i/n A 13.7 - 14 Mm C2H2 HCN? 8 - 10 Mm E 8.6 M"i Unknown 10 - 13 Mm E 11.3 - 11 .7 M«> SiC Group III 10 - 13 MJn E 11.3 - 11 .7 tun SiC B - 23 Htn C Amorphous carbon 1 The letter in this column indicates the nature o-f the -feature: A = absorption; E = emission; C indicates the presence of continuum opacity. II. LRS SPECTRA The sample consists of 304 carbon stars with entries in the LRS catalog (Papers I-III). The LRS spectra have been divided into three groups. Group I consists of nine stars with 9.7 and 18 tun silicate features in their LRS spectra pointing to oxygen-rich dust in the circumstellar shell. These sources are discussed in Paper I. The remaining stars all have spectra with carbon-rich dust features. Using NIR photometry we have shown that in the group II spectra the stellar photosphere is the dominant continuum. The NIR color temperature is of the order of 25OO K. Paper II contains a discussion of sources with this class of spectra. The continuum in the group III spectra is probably due to amorphous carbon dust. -

Constellation at Your Fingertips: Cygnus

The National Optical Astronomy Observatory’s Dark Skies and Energy Education Program Constellation at Your Fingertips: Cygnus (Cygnus version adapted from Constellation at Your Fingertips: Orion at www.globeatnight.org) Grades: 3rd - 8th grade Overview: Constellation at Your Fingertips introduces the novice constellation hunter to a method for spotting the main stars in the constellation, Cygnus, the swan. Students will make an outline of the constellation used to locate the stars in Cygnus and visualize its shape. This lesson will engage children and first-time night sky viewers in observations of the night sky. The lesson links history, Greek mythology, literature, and astronomy. Once the constellation is identified, it may be easy to find the summer triangle. The simplicity of Cygnus makes locating and observing it exciting for young learners. More on Cygnus is at the Great World Wide Star Count at http://www.starcount.org. Materials for another citizen-science star hunt, Globe at Night, are available at http://www.globeatnight.org. Purpose: Students will use the this activity to visualize the constellation of Cygnus. This will help them more easily participate in the Great World Wide Star Count citizen-science campaign. The campaign asks participants to match one of 7 different charts of Cygnus with what the participant sees toward Cygnus. Chart 1 has only a few stars. Chart 7 has many. What they will be recording for the campaign is the chart with the faintest star they see. In many cases, observations over years will build knowledge of how light pollution changes over time. Why is this important to astronomers? What causes the variation year to year? The focus is on light pollution and the options we have as consumers when purchasing outdoor lighting and shields. -

The Kepler Characterization of the Variability Among A- and F-Type Stars I

A&A 534, A125 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117368 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics The Kepler characterization of the variability among A- and F-type stars I. General overview K. Uytterhoeven1,2,3,A.Moya4, A. Grigahcène5,J.A.Guzik6, J. Gutiérrez-Soto7,8,9, B. Smalley10, G. Handler11,12, L. A. Balona13,E.Niemczura14, L. Fox Machado15,S.Benatti16,17, E. Chapellier18, A. Tkachenko19, R. Szabó20, J. C. Suárez7,V.Ripepi21, J. Pascual7, P. Mathias22, S. Martín-Ruíz7,H.Lehmann23, J. Jackiewicz24,S.Hekker25,26, M. Gruberbauer27,11,R.A.García1, X. Dumusque5,28,D.Díaz-Fraile7,P.Bradley29, V. Antoci11,M.Roth2,B.Leroy8, S. J. Murphy30,P.DeCat31, J. Cuypers31, H. Kjeldsen32, J. Christensen-Dalsgaard32 ,M.Breger11,33, A. Pigulski14, L. L. Kiss20,34, M. Still35, S. E. Thompson36,andJ.VanCleve36 (Affiliations can be found after the references) Received 30 May 2011 / Accepted 29 June 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The Kepler spacecraft is providing time series of photometric data with micromagnitude precision for hundreds of A-F type stars. Aims. We present a first general characterization of the pulsational behaviour of A-F type stars as observed in the Kepler light curves of a sample of 750 candidate A-F type stars, and observationally investigate the relation between γ Doradus (γ Dor), δ Scuti (δ Sct), and hybrid stars. Methods. We compile a database of physical parameters for the sample stars from the literature and new ground-based observations. We analyse the Kepler light curve of each star and extract the pulsational frequencies using different frequency analysis methods. -

Shadows of Venus 29 November 2005

Shadows of Venus 29 November 2005 he continues, "I found myself in Sir Patrick's home. The conversation turned to things that had never been photographed. He told me that there were few, if any, decent photographs of a shadow caused by the light from Venus. So the challenge was set." On Nov. 18, Lawrence took his own young boys, Richard (age 14) and Douglas (age 12), to a beach near their home. "There was no ambient lighting, no moon, no manmade lights, only Venus and the stars. It was the perfect venue to make my attempt." On that night, and again two nights later, they photographed shadows of their camera's tripod, shadows of patterns cut from cardboard, and The planet Venus is growing so bright, it's shadows of the boy's hands--all by the light of actually casting shadows. Venus. It's often said (by astronomers) that Venus is bright The shadows were very delicate, "the slightest enough to cast shadows. So where are they? Few movement destroyed their distinct sharpness. It is people have ever seen a Venus shadow. But difficult," he adds, "for a cold human being to stand they're there, elusive and delicate--and, if you still long enough for the amount of time needed to appreciate rare things, a thrill to witness. Attention, catch the faint Venusian shadow." thrill-seekers: Venus is reaching its peak brightness for 2005 and casting its very best Difficult, yes, but worth the effort, he says. After all, shadows right now. how many people have seen themselves silhouetted by the light of another planet? Image: Richard and Douglas Lawrence make hand shadows using the light of Venus. -

The Planets for 1955 24 Eclipses, 1955 ------29 the Sky and Astronomical Phenomena Month by Month - - 30 Phenomena of Jupiter’S S a Te Llite S

THE OBSERVER’S HANDBOOK FOR 1955 PUBLISHED BY The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada C. A. C H A N T, E d ito r RUTH J. NORTHCOTT, A s s is t a n t E d ito r DAVID DUNLAP OBSERVATORY FORTY-SEVENTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION P r i c e 50 C e n t s TORONTO 13 Ross S t r e e t Printed for th e Society By the University of Toronto Press THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA The Society was incorporated in 1890 as The Astronomical and Physical Society of Toronto, assuming its present name in 1903. For many years the Toronto organization existed alone, but now the Society is national in extent, having active Centres in Montreal and Quebec, P.Q.; Ottawa, Toronto, Hamilton, London, and Windsor, Ontario; Winnipeg, Man.; Saskatoon, Sask.; Edmonton, Alta.; Vancouver and Victoria, B.C. As well as nearly 1000 members of these Canadian Centres, there are nearly 400 members not attached to any Centre, mostly resident in other nations, while some 200 additional institutions or persons are on the regular mailing list of our publications. The Society publishes a bi-monthly J o u r n a l and a yearly O b s e r v e r ’s H a n d b o o k . Single copies of the J o u r n a l are 50 cents, and of the H a n d b o o k , 50 cents. Membership is open to anyone interested in astronomy. Annual dues, $3.00; life membership, $40.00. -

A Review of the Disc Instability Model for Dwarf Novae, Soft X-Ray Transients and Related Objects a J.M

A review of the disc instability model for dwarf novae, soft X-ray transients and related objects a J.M. Hameury aObservatoire Astronomique de Strasbourg ARTICLEINFO ABSTRACT Keywords: I review the basics of the disc instability model (DIM) for dwarf novae and soft-X-ray transients Cataclysmic variable and its most recent developments, as well as the current limitations of the model, focusing on the Accretion discs dwarf nova case. Although the DIM uses the Shakura-Sunyaev prescription for angular momentum X-ray binaries transport, which we know now to be at best inaccurate, it is surprisingly efficient in reproducing the outbursts of dwarf novae and soft X-ray transients, provided that some ingredients, such as irradiation of the accretion disc and of the donor star, mass transfer variations, truncation of the inner disc, etc., are added to the basic model. As recently realized, taking into account the existence of winds and outflows and of the torque they exert on the accretion disc may significantly impact the model. I also discuss the origin of the superoutbursts that are probably due to a combination of variations of the mass transfer rate and of a tidal instability. I finally mention a number of unsolved problems and caveats, among which the most embarrassing one is the modelling of the low state. Despite significant progresses in the past few years both on our understanding of angular momentum transport, the DIM is still needed for understanding transient systems. 1. Introduction tems using Doppler tomography techniques (Steeghs et al. 1997; Marsh and Horne 1988; see also Marsh and Schwope Dwarf novae (DNe) are cataclysmic variables (CV) that 2016 for a recent review). -

The Multi-Periodicity of W Cygni

The multi-periodicity of W Cygni J. J. Howarth The behaviour of the variable star W Cygni has been analysed from the past 89 years of BAA observations. Periods of approximately 131 and 234 days are evident, both being subject to apparently random shifts in phase and amplitude. A report of the Variable Star Section Director: J. E. Isles Introduction BAA observations from 1907 to 1918, in which they deduced periods of 129.6 days of amplitude (half peak The variable star W Cygni, RA 21h 36m 02s, Dec 45° to peak) 0.36 mag, and 243 days of amplitude 0.26 13 22' 29" (2000.0) (GC 30250, HD 205730, SAO 51079) mag. A third possible variation of period 1944 days is has been on the programme of the BAA Variable Star also mentioned. The authors refer to 'halts' in the cyclic Section since 1891. Although analysis has been under variations, which effectively represent sudden phase taken on some of these observations, as described shifts. In 1920 the same authors wrote a second note below, no attempt has been made to study with modern taking into account observations by Sawyer (men techniques the whole span of data which now extends tioned above) over the years 1885-1895. These extra to almost a century. This paper describes the computer observations confirmed the first two periods, but cast 14 isation of the BAA observations of W Cygni and the doubt on the third. Further 'halts' were found. subsequent analysis of the light curve. Dinsmore Alter, in 1929, applied a correlation tech nique to both Turner and Blagg's data and later BAA data.15 The established periods of Turner and Blagg1314 were increased to 132 and 249 days, and a further Background period of about 1100 days was noted. -

Stars and Their Spectra: an Introduction to the Spectral Sequence Second Edition James B

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89954-3 - Stars and Their Spectra: An Introduction to the Spectral Sequence Second Edition James B. Kaler Index More information Star index Stars are arranged by the Latin genitive of their constellation of residence, with other star names interspersed alphabetically. Within a constellation, Bayer Greek letters are given first, followed by Roman letters, Flamsteed numbers, variable stars arranged in traditional order (see Section 1.11), and then other names that take on genitive form. Stellar spectra are indicated by an asterisk. The best-known proper names have priority over their Greek-letter names. Spectra of the Sun and of nebulae are included as well. Abell 21 nucleus, see a Aurigae, see Capella Abell 78 nucleus, 327* ε Aurigae, 178, 186 Achernar, 9, 243, 264, 274 z Aurigae, 177, 186 Acrux, see Alpha Crucis Z Aurigae, 186, 269* Adhara, see Epsilon Canis Majoris AB Aurigae, 255 Albireo, 26 Alcor, 26, 177, 241, 243, 272* Barnard’s Star, 129–130, 131 Aldebaran, 9, 27, 80*, 163, 165 Betelgeuse, 2, 9, 16, 18, 20, 73, 74*, 79, Algol, 20, 26, 176–177, 271*, 333, 366 80*, 88, 104–105, 106*, 110*, 113, Altair, 9, 236, 241, 250 115, 118, 122, 187, 216, 264 a Andromedae, 273, 273* image of, 114 b Andromedae, 164 BDþ284211, 285* g Andromedae, 26 Bl 253* u Andromedae A, 218* a Boo¨tis, see Arcturus u Andromedae B, 109* g Boo¨tis, 243 Z Andromedae, 337 Z Boo¨tis, 185 Antares, 10, 73, 104–105, 113, 115, 118, l Boo¨tis, 254, 280, 314 122, 174* s Boo¨tis, 218* 53 Aquarii A, 195 53 Aquarii B, 195 T Camelopardalis, -

Present Status and Future Directions of the EVN

http://www.evlbi.org/ Present status and future directions of the EVN Michael Lindqvist, Onsala Space Observatory Zsolt Paragi, JIVE Onsala Space Observatory http://www.evlbi.org/ Thanks Tasso! Onsala Space Observatory http://www.evlbi.org/ VLBI science • Radio jet & black hole physics • Radio source evolution • Astrometry • Galactic and extra-galactic masers • Gravitational lenses • Supernovae and gamma-ray-burst studies • Nearby and distant starburst galaxies • Nature of faint radio source population • HI absorption studies in AGN • Space science VLBI • Transients • SETI Onsala Space Observatory http://www.evlbi.org/ Description of the EVN • The European VLBI Network (EVN) was formed in 1980. Today it includes 15 major institutes, including the Joint Institute for VLBI ERIC, JIVE • JIVE operates EVN correlator. JIVE is also involved in supporting EVN users and operations of EVN as a facility. JIVE has officially been established as an European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ERIC). • The EVN operates an “open sky” policy • No standing centralised budget for the EVN - distributed European facility Onsala Space Observatory http://www.evlbi.org/ The network Onsala Space Observatory http://www.evlbi.org/ EVN and e-VLBI From tape reel to intercontinental light paths • Pieces falling into place around 2003: – Introduction of Mark5 recording system (game changer) by Haystack Observatory – Emergence of high bandwidth optical fibre networks e-VLBI JIVE Hot scienceJIVE • The development of e-VLBI has been spearheaded by the JIVE/EVN (EXPReS, Garrett) • In this way, the EVN/JIVE is a recognized SKA pathfinder Onsala Space Observatory http://www.evlbi.org/ e-VLBI - rapid turn-around • e-VLBI has made rapid turn-around possible – X-ray, γ-ray binaries in flaring states (including novae) – AGN γ-ray outbursts — locus of VHE emission – Other high-energy flaring (e.g., Crab) – Outbursts in Mira variables (spectral-line) – Just-exploded GRBs, SNe – Binaries (incl.