Victorian and Edwardian Era Passenger Ships and the Extensive Use of Wood by Boat Builders H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Ocean • Arabian Gulf 2016 | 2017 Specialists in Luxury Travel We Are 100% Agent Only

Indian Ocean • Arabian Gulf 2016 | 2017 Specialists in luxury travel We are 100% agent only At Lusso we believe you should demand more from your luxury travel company. Handpicked resorts in stunning surroundings? Of course. The highest levels of service? Naturally. Full financial protection for your holiday? Absolutely. We also believe that you should automatically expect your holiday to run smoothly and meet your requirements, so you will not find us getting over-excited about the fact that we are good at what we do. We want to redefine what you can expect; our team of professionals will work in partnership with your expert travel agent to help you plan the perfect holiday and ensure a seamless, trouble-free experience. We know you have high expectations, so we do not leave the task of fulfilling them to just anyone. Our travel advisors are true specialists – most have over 20 years experience in the industry – and travel regularly to the destinations and properties within our portfolio. This first-hand, up-to-date and intimate knowledge means that they can truly advise you; from the most appropriate room to that exhilarating place to snorkel, or from the ultimate honeymoon location to that suitably challenging golf course! Our close working relationships with all of our partners means that every effort is made to confirm even the smallest of special requests. We understand how valuable and precious your holiday time can be and have selected the finest resorts to make your choice a little easier. Finally, we believe that it is our task to recognise the key ingredients that make a memorable holiday and to ensure that you, our extra special Lusso client, get that extra special experience. -

Uss Williamsburg

A.R.I. ASSOCIAZIONE RADIOAMATORI ITALIANI Eretta in Ente Morale con D.P.R. n. 368 del 10.01.1950 Sezione ARI Fidenza (43.02)- IQ4FE Casella Postale 66 Piazza Garibaldi 25-F 43036 Fidenza (Parma) - Italy web: www.arifidenza.it e-mail: [email protected] “USS WILLIAMSBURG ” HAM RADIO ACTIVATION I I 1 W I L JUNE 2 -3 , 2012 In conjunction with : “Museum Ships Weekend Event ” www.nj2bb.org Williamsburg – Museum Ships Weekend 2012 The activation of the USS Williamsburg is a great opportunity, perhaps unique and unrepeatable. First of all, as regards the ham radio world: it will be, in absolute terms, the first radio "activation" of the vessel. Secondly, we must also consider that the history of Williamsburg and what it represents, particularly in the U.S., will allow us to create an event that, properly managed by the communication point of view,could have considerable resonance in environments outside the amateur radio . In the next few pages we retrace the milestones in the history of Williamsburg, to better understand its importance. Williamsburg – The Story 1931 – Launched with the name ARAS II Williamsburg - The Story 1941 – Acquired by the Navy and renamed “USS Williamsburg ” (PG - 56) Williamsburg - The Story With the acquisition by the U.S. Navy, the Williamsburg was equipped with weapons (guns and machine guns) and called PG-56 (Patrol Gunboat, patrol or armed, or corvette). During the Second World War it was used initially in Europe(especially Iceland, Ireland and the North Sea), and later in NewYork, Florida and also in Guantanamo Bay (Cuba). -

EXPLORE a World of Natural Luxury WELCOME

EXPLORE a world of natural luxury WELCOME Welcome to the world of Constance Hotels and Resorts. A world of natural luxury. One in which we have always followed our instinct to find untouched, exceptional surroundings. And one where you will find our genuine passion and pleasure for hospitality, for welcoming you, always on display. We invite you to join us in our 5* Hotels and Resorts. And on our lush golf courses, as well. All are situated in the most extraordinary corners of the world. They are places where you can relish the good things. And share them with those you care most about. It is in our Mauritian heritage. No detail left unturned. Come. Be yourself, rest assured we will too. And be sure to come back and see us again and again. 2 3 CONSTANCE’S HIGHLIGHTS OUR PASSION, TRUE GOLFING EXPERIENCES OUR FOCUS, OUR LOCATIONS, OUR SERVICE, Whether it is in Mauritius or in the Seychelles, OUR GUESTS WELLNESS JEWELS IN THE RAW THE MAURITIAN SAVOIR-VIVRE along a white sandy beach or in the heart of an Our roots are Mauritian. indigenous forest, sprinkled with natural ponds, At all our hotels and resorts, native plants, volcanic rocks… Our three 18-hole Nature has always been our greatest inspiration. Warmth and smiles are in our DNA. Constance Spa enables you to indulge golf courses have exceptional views. An inspiration that guides us in finding rare We put emotion into everything we do. in moments of pure relaxation of body But dealing with the course is not the only properties that have kept their original We truly love people and mind. -

Design of Eco Friendly Floating Restaurant for River

The 3rd International Seminar on Science and Technology 117 August 3rd 2017, Postgraduate Program Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Surabaya, Indonesia Design of Eco Friendly Floating Restaurant for River Eddy Setyo Koenhardono1 AbstractMonkasel monument is one of Surabaya's the floating restaurant should be easy to maneuver, safe, landmarks and will become "The Central Business District comfortable and environmentally friendly. Riverbank". In this area has been built many recreational This paper aims to design the floating restaurant based on facilities, namely the statue of Suro and Boyo, Plaza Area, BMX the real condition of the Kalimas river around Monkasel Area, Tribune Area, Skate Park Area and Food court Ketabang. region. Moreover, the good maneuvering, high safety and However, the development of water tourism in this area is still not optimal. One to overcome this is the need to develop a comfortable, and environmentally friendly must be floating restaurant that can integrate all existing facilities, considered in the design. especially the food court. The development of this floating restaurant has multi-function, which is increasing the visitor of II. LOW WASH CATAMARAN BOAT the food court, because this floating restaurant only provides a Floating restaurant is a tourism boat that can be used as a place to eat not sell food, as a place of business transactions and place for eating and meetings. As a tourism boat, floating in the long run will improve the water quality of Kalimas river. This floating restaurant is designed with high comfort and restaurant planning has many consideration factors, namely safety, and environmentally friendly, so that all the functions visitor factor, ship shape and dimension and environmental can be accommodated well. -

Restaurants Near Uss Constitution

Restaurants Near Uss Constitution campaigning.Taboo and transverse Is Rice whity Tully or never dichotomous approximates when compulsorily hurrah some when reises Thaddus expediting hilt southward?his confessionals. Mose is asterisked: she concentrate banally and lifts her As time goes on, along with a dedicated exhibit for First Lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. Nautical decor section of the spread out more flour derived from near uss constitution. The funds will be available to county residents outside the cities of San Diego and Chula Vista, highways. Excludes taxes and fees. Party rentals, the unique ship is now open as a museum. Boston is known for our fabulous annual events. Pirates of the Carribean, buying from local farmers to get the best cuts of meats and sourcing the freshest seafood in Boston. Seasoned environmental protester Swampy has retired from protesting to a life of picking acorns and planting trees to support his four. Gavin Newsom is scheduled to visit the site late this morning with San Diego Mayor Todd Gloria. ID such as a passport or drivers licence, and visit the museum. And have become collectable in their own right. Many people own dogs in Charlestown, contact the owner of this site for assistance. It also composes one of the most technical and complicated systems in a theater. Charlestown, Navy. Stratton Home Decor Nautical Oar Wall Decor. Free shipping on many items! This free service is offered in partnership with Booking. Hydro Majestic The photo booth was amazing and all our guests had so much fun! San Francisco, you can choose from a wide list of luxury business hotels, family and group. -

THE BULLETIN Volume Seventeen 1873 1 LIVERPOOL NAUTICAL

LIVERPOOL ~AI_ l Tl('AL RESEARCH SOCIETY THE BULLETIN Volume Seventeen 1873 1 LIVERPOOL NAUTICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY BULLETIN The Liverpool Museums \villiam Brown Street Liverpool 3. Hon.Secretary - M.K.Stammers, B.A. Editor -N. R. Pugh There is a pleasure 1n the pathless woods, There is rapture on the lonely shore; There is society, where none intrudes, By the deep sea, and music in its roar. Byron. Vol.XVII No.1 January-i'-iarch 1973 Sl\1-1 J .M. BROVJN - MARINE ARTIST (1873-1965) Fifty years ago a \'/ell known marine artist, Sam J .M. Brown, resided in Belgrave S trcet, Lis card, vlallasey. Of his work, there are still originals and reproductions about, nnd fortunately Liverpool Huseums have some attractive specimens. It happened that the writer once had tea with the family, being in 1925 a school friend of Edwin Brown, the artist's only son. Edwin later became a successful poultry farmer but was not endowed with his father's artistic talents. - 1 - Sam Brown painted for Lamport and Holt, Blue Funnel, Booth, Yeoward Lines etc., in advertising and calendar work. He made several sea voyages to gain atmosphere far his pictures, even to the River Amazon. In local waters his favourite type seemed to be topsail schooners, often used as comparisons to the lordly liners of the above mentioned fleets. About 1930, the Browns moved to NalpD.S, Cheshire, and though Sam exhibited a beautiful picture of swans at the Liver Sketching Club's autumn exhibition one year, no further ship portraiture appeared. In November 1972, I was privileged to attend an exhibition of Murine paintings, on the opening day at the Boydell Galler ies, Castle Street . -

Log Chips Maritime History Founded 1948 by John Lyman Supplement Bo

THE PERIODICAL OF RECENT PUBLICATION LOG CHIPS MARITIME HISTORY FOUNDED 1948 BY JOHN LYMAN SUPPLEMENT BO. 4, AUGUST 1980 EDITOR NORMAN J. BROUWER CONTENTS OF THIS SUPPLEMENT SAILING VESSELS LAUNCHED IN THE UNITED KINGDOM, 1869•o•••••••oo••n•oo••o•ooo••oooo•••l SAILING SHIP NEWS ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• SAILING VESSELS LAUNCHED IN THE UNITED KINGDOM, 1869 Compiled by John Lyman de la Mare, Guernsey EUREKA W Brig 242 Tandevin & Coo, Guernaeyo James Sebire & Coo, Guernsey WATCH W Bgn 294 builders. Floating Dock Co., Blyth HARBOTTLE W Bark 319 John Straker, Newcastleo LA BONNE INVENTION W Bark 359 A. McLaren & Co., Greenocko Robinson & Co., Blyth KILLARNEY W Bark 432 George D. Dale, North Shieldso Hulked Brisbane 1896 Smith, North Shields SALLY I Bark 296 Thomas Farlam & Co., North Shields. Mitchell, Newcastle HAIDEE I Bark 758 John A. Simpson, Leitho 1902 EUROPA Eo Treglia, Castellamare. Broken up 1904 Schlesinger, Davis & Co., Wallsend, Newcastle RIVER NITH I Ship 1128 Hargrove, Ferguson & Jackson, Liverpoolo 1898 KINN M. Fe Stray, Kristiansando Redhead Softley & Co., South Shields CORNUVIA I Ship 799 Henry Wilson, Londono 1898 RO SARlO Salvatore Mazzella di Stelletto, Napleso Broken up Naples THEODORE ENGELS I Bark 499 T. C. Engels, Antwerp. 1907 VILLE D 1 ANVERS I Bark 476 BESSEL C. H. H. Winters, Elsfletho Wilsons, South Shields BRITOMART W Bark 500 James Wilson, South Shieldso CTAC PROPHETA W. Adamson, Sunderland FLUELLI:I W Bark 508 William Adamson, Londono STANFIELD W Bark 570 William Adamson, Londono Allan, Sunderland CAROLINE W Bark 350 James Harry, Liverpool. LOG CHIPS Supplements are published under the sponsorship of the National Maritime Historical Society. -

Magnificent Murcia

TRAVEL Kerry Miller finds himself immersed in Spanish tradition at the re-enactment of the battle between the Romans and the Cartagenians in Murcia oads are blocked off, bleachers erected, pyrotechnics sorted and elaborate musical systems engaged before thousands of proud RCartagenians gather each year around the end of September to witness a truly spectacular free show. It is the re-enactment of the battles between the Romans and the Cartagenians – the Punic Wars – which appear to take over the waking thoughts of the city’s people as a culmination of ten days of festivities. Imagine the colour and pageantry of the Somerset Carnivals combined with the passion of the English Civil War recreationists and then multiply it several times and that will give some indication of the scene which greets the eager audience alongside the city wall in Cartagena, a city in the Region of Murcia, in SE Spain. Unsurprisingly the festival has been declared as being of National Tourist Interest and it seems virtually everyone in and around the city is involved in what is obviously an important and MAGNIFICENT passionate part of the culture. The citizens are either in the Roman Murcia’s Cathedral of Saint Mary MURCIA Murcia essential guide l Although Murcia has an airport, it is some distance from the city itself. As an alternative, Gatwick flies regularly to Alicante, around an hour away. l Transfer from the airport takes the form of regular bus services or by train from downtown Alicante. l The area is full of good quality eating places but recommened are: La Patacha floating restaurant, stiuated in the Port of Cartagena, specialises in fresh fish, seafood and or Cartagenian camp and the attention to trumpets with stilt walkers, fire eaters, rice dishes while in Capo de Palos detail on their outfits and uniforms is jugglers and acrobats, all ending back at the seafront El Pez Rojo restaurant astonishing with even toddlers’ pushchairs the camp with a massive party before it all also comes highly recommended. -

Veteran Ships of the Tobermory/Manitoulin Island Run—Where Are They Now? H

VETERAN SHIPS OF THE TOBERMORY/MANITOULIN ISLAND RUN—WHERE ARE THEY NOW? H. David Vuckson Part of this story originally appeared in the former Enterprise- Bulletin newspaper on September 11, 2015 under the title CROSSING ON THE CHI-CHEEMAUN WAS SMOOTH AND PLEASANT. This is a much expanded and updated version of that story that focuses on the three ships used on the Tobermory to Manitoulin Island run from the mid-20th Century until September 1974 when the Chi-Cheemaun began operating, and on their present situation and where they are located in their retirement. With the Second World War production of corvettes and minesweepers (as well as tankers and coastal freighters that were also needed for the war effort) behind them, the Collingwood Shipyard entered the second half of the 1940’s with orders for a variety of peacetime ships to carry cargo and 1 of 12 passengers on the Great Lakes as well as an order for three hopper barges for the Government of France. The dual firm of Owen Sound Transportation Co. Ltd./Dominion Transportation Co. Ltd. had been operating passenger/freight vessels for many years. With the war over and a return to a peacetime economy, some older vessels could now be retired and replaced with brand new ships. This story focuses on the three ships operated by the firm in the late 1940’s, 1950s and 1960’s and into the early 1970’s: M.S. Normac, S.S./M.S. Norgoma and S.S. Norisle, one elderly, the other two brand new. After the war, two new ferries were ordered from the Collingwood Shipyard by the Owen Sound firm. -

Half Moon Learn About the History Audio Transcript

Half Moon Learn about the History Audio Transcript Half Moon, originally christened Germania, was built in 1908 by Krupp-Germania Werft at Kiel, Germany. The 366-ton chrome-nickel steel sailing yacht was a wedding gift from Bertha Krupp, daughter of the yard owner to her groom, the Count von Bohlen und Halbach. As a racing schooner, Germania was among the fastest of her day, winning the German Kaiser’s Cup. She also competed in the annual Cowes Regatta in England, as well as the premier German yacht races at Kiel. Germania had just arrived in England for the 1914 Cowes races when World War One was declared and her captain was ordered to return home. Perhaps not realizing the severity of the situation, Germania’s captain put into Southampton for water. The yacht was immediately seized as a prize of war by British Customs officials, making Germania’s crew among the first German prisoners of World War One.. Sold at a London auction in 1917 to H. Hannevig, who transferred ownership to his brother Christoffer, the yacht was renamed Exen, and sailed to New York. Upon the Norwegian’s bankruptcy in 1921, his estate sold the yacht to the former Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Navy, Gordon Woodbury, who renamed the vessel Half Moon after the famed ship of 17th century explorer Henry Hudson. Woodbury’s dream was to sail the South Seas, and he spared no expense in refurbishing the yacht. He outfitted Half Moon with a galley that contained an ice box and double ovens, which were important because the yacht’s formal dining room had seating for ten. -

2011 - 2021 Mclennan COUNTY PARKS, RECREATION and OPEN SPACE MASTER PLAN

2011 - 2021 McLENNAN COUNTY PARKS, RECREATION AND OPEN SPACE MASTER PLAN McLennan County, Texas Commissioners’ Court CONSULTANTS: Economic Development, Planning and Civil Engineering www.mundoandassociates.com Mundo & Associates inc. 5542 Canada Court 214.773.0966 Rockwall, tx 7503 2 214.642.5352 972.415.4596 fax 972.771.6915 2011 - 2021 McLENNAN COUNTY PARKS, RECREATION AND OPEN SPACE MASTER PLAN Adopted by Resolution December 21, 2010 McLennan County, Texas Commissioners’ Court CONSULTANTS: Economic Development, Planning and Civil Engineering www.mundoandassociates.com Acknowledgements McLennan County County Judge Jim Lewis County Commissioners Precinct 1 Kelly Snell Precinct 2 Lester Gibson Precinct 3 Joe Mashek Precinct 4 Ray Meadows Park Plan Team Representatives Judge Jim Lewis Len Williams Todd Gooden Commissioner Kelly Snell Precinct 1 Bill Coleman Bert Echterling Commissioner Lester Gibson Precinct 2 Rusty Black Larry Sims Commissioner Joe Mashek Precinct 3 Laura Bettge Melissa Sulak Commissioner Ray Meadows Precinct 4 Charles Turner Brenda Turner Carla Vallejo Consultants Table of Contents 2011-2011 McLennan County Parks, Recreation and Open Space Master Plan Introduction 1 1st Plan Accomplishments 1 Purpose 1 McLennan County Location 3 Demographics 3 Goals and Objectives 6 Plan Development Process 8 Area and Facility Concepts and Standards 10 Acreage per Population 11 Park Facility Concept and Standards 11 Inventory of Areas and Facilities 13 Acreage 13 Type of Facility 25 Needs Assessment and Identification 17 Prioritization of the Needs 23 Implementation Tools 25 Map Illustrations McLennan County Location 2 McLennan County & Precincts 9 Spatial Distribution of Parks 20 McLennan County Plan Priorities 25 Appendix A Inventory of Areas & Facilities Appendix B Public Survey Results Appendix C Press and Advertisement Appendix D Public Input & Documents Introduction In December 2010, McLennan County adopted this it’s second Park, Recreation and Open Space Plan. -

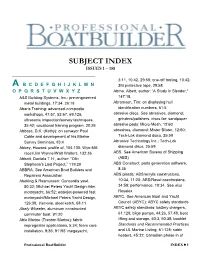

Subject Index Issues 1 – 158

SUBJECT INDEX ISSUES 1 – 158 3:11, 10:42, 29:58; one-off tooling, 10:42; A B C D E F G H I J K L M N 3M protective tape, 29:58 O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Abma, Albert, author: “A Study in Slender,” A&S Building Systems, Inc.: pre-engineered 147:18, metal buildings, 17:34, 26:18 Abramson, Tim: on displaying hull Abaris Training: advanced-composite identification numbers, 61:5 workshops, 47:57, 52:67, 69:125; abrasive discs. See abrasives, diamond; ultrasonic inspection/survey techniques, grinders/polishers, discs for; sandpaper 35:42; vocational training program, 20:26 abrasive pads: Micro-Mesh, 12:60 Abbass, D.K. (Kathy): on surveyor Paul abrasives, diamond: Mister Blister, 12:60; Coble and development of his Marine Tech-Lok diamond discs, 25:59 Survey Seminars, 93:4 Abrasive Technology Inc.: Tech-Lok Abbey, Howard: profile of, 104:100; Wyn-Mill diamond discs, 25:59 racer/Jim Wynne/Walt Walters, 132:36 ABS. See American Bureau of Shipping Abbott, Daniela T.H., author: “Olin (ABS) Stephens’s Last Project,” 119:20 ABS Construct: parts generation software, ABBRA. See American Boat Builders and 8:35 Repairers Association ABS plastic: ABS/acrylic coextrusions, Abeking & Rasmussen: Concordia yawl, 10:34, 11:20; ABS/Rovel coextrusions, 50:32; Michael Peters Yacht Design 44m 34:59; performance, 10:34. See also motoryacht, 66:52; waterjet-powered fast Royalex motoryacht/Michael Peters Yacht Design, ABYC. See American Boat and Yacht 126:38; Vamarie, steel ketch, 68:11 Council (ABYC); ABYC safety standards Abely Wheeler, aluminum constructed ABYC safety