Package 'Phontools'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Issues in the Distribution of the Glottal Stop

Theoretical Issues in the Representation of the Glottal Stop in Blackfoot* Tyler Peterson University of British Columbia 1.0 Introduction This working paper examines the phonemic and phonetic status and distribution of the glottal stop in Blackfoot.1 Observe the phonemic distribution (1), four phonological operations (2), and three surface realizations (3) of the glottal stop: (1) a. otsi ‘to swim’ c. otsi/ ‘to splash with water’ b. o/tsi ‘to take’ (2) a. Metathesis: V/VC ® VV/C nitáó/mai/takiwa nit-á/-omai/takiwa 1-INCHOAT-believe ‘now I believe’ b. Metathesis ® Deletion: V/VùC ® VVù/C ® VVùC kátaookaawaatsi káta/-ookaa-waatsi INTERROG-sponsor.sundance-3s.NONAFFIRM ‘Did she sponsor a sundance?’ (Frantz, 1997: 154) c. Metathesis ® Degemination: V/V/C ® VV//C ® VV/C áó/tooyiniki á/-o/too-yiniki INCHOAT-arrive(AI)-1s/2s ‘when I/you arrive’ d. Metathesis ® Deletion ® V-lengthening: V/VC ® VV/C ® VVùC kátaoottakiwaatsi káta/-ottaki-waatsi INTEROG-bartender-3s.NONAFFIRM ‘Is he a bartender?’ (Frantz, 1997) (3) Surface realizations: [V/C] ~ [VV0C] ~ [VùC] aikai/ni ‘He dies’ a. [aIkaI/ni] b. [aIkaII0ni] c. [aIkajni] The glottal stop appears to have a unique status within the Blackfoot consonant inventory. The examples in (1) (and §2.1 below) suggest that it appears as a fully contrastive phoneme in the language. However, the glottal stop is put through variety of phonological processes (metathesis, syncope and degemination) that no other consonant in the language is subject to. Also, it has a variety of surfaces realizations in the form of glottalization on an adjacent vowel (cf. -

Towards Zero-Shot Learning for Automatic Phonemic Transcription

The Thirty-Fourth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-20) Towards Zero-Shot Learning for Automatic Phonemic Transcription Xinjian Li, Siddharth Dalmia, David R. Mortensen, Juncheng Li, Alan W Black, Florian Metze Language Technologies Institute, School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University {xinjianl, sdalmia, dmortens, junchenl, awb, fmetze}@cs.cmu.edu Abstract Hermann and Goldwater 2018), which typically uses an un- supervised technique to learn representations which can be Automatic phonemic transcription tools are useful for low- resource language documentation. However, due to the lack used towards speech processing tasks. of training sets, only a tiny fraction of languages have phone- However, those unsupervised approaches could not gener- mic transcription tools. Fortunately, multilingual acoustic ate phonemes directly and there has been few works study- modeling provides a solution given limited audio training ing zero-shot learning for unseen phonemes transcription, data. A more challenging problem is to build phonemic tran- which consist of learning an acoustic model without any au- scribers for languages with zero training data. The difficulty dio data or text data for a given target language and unseen of this task is that phoneme inventories often differ between phonemes. In this work, we aim to solve this problem to the training languages and the target language, making it in- transcribe unseen phonemes for unseen languages without feasible to recognize unseen phonemes. In this work, we ad- dress this problem by adopting the idea of zero-shot learning. considering any target data, audio or text. Our model is able to recognize unseen phonemes in the tar- The prediction of unseen objects has been studied for a get language without any training data. -

Velar Segments in Old English and Old Irish

In: Jacek Fisiak (ed.) Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Historical Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1985, 267-79. Velar segments in Old English and Old Irish Raymond Hickey University of Bonn The purpose of this paper is to look at a section of the phoneme inventories of the oldest attested stage of English and Irish, velar segments, to see how they are manifested phonetically and to consider how they relate to each other on the phonological level. The reason I have chosen to look at two languages is that it is precisely when one compares two language systems that one notices that structural differences between languages on one level will be correlated by differences on other levels demonstrating their interrelatedness. Furthermore it is necessary to view segments on a given level in relation to other segments. The group under consideration here is just one of several groups. Velar segments viewed within the phonological system of both Old English and Old Irish cor relate with three other major groups, defined by place of articulation: palatals, dentals, and labials. The relationship between these groups is not the same in each language for reasons which are morphological: in Old Irish changes in grammatical category are frequently indicated by palatalizing a final non-palatal segment (labial, dental, or velar). The same function in Old English is fulfilled by suffixes and /or prefixes. This has meant that for Old English the phonetically natural and lower-level alternation of velar elements with palatal elements in a palatal environ ment was to be found whereas in Old Irish this alternation had been denaturalized and had lost its automatic character. -

Dynamic Modeling for Chinese Shaanxi Xi'an Dialect Visual

UNIVERSITY OF MISKOLC FACULTY OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING AND INFORMATICS Dynamic Modeling for Chinese Shaanxi Xi’an Dialect Visual Speech Summary of PhD dissertation Lu Zhao Information Science ‘JÓZSEF HATVANY’ DOCTORAL SCHOOL OF INFORMATION SCIENCE, ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ACADEMIC SUPERVISOR Dr. László Czap Miskolc 2020 Content Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1 Phonetic Aspects of the Chinese Shaanxi Xi’an Dialect ......................... 3 1.1. Design of the Chinese Shaanxi Xi’an Dialect X-SAMPA ..................... 3 1.2. Theoretical method of transcription from the Chinese character to X-SAMPA .................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 2 Visemes of the Chinese Shaanxi Xi’an Dialect....................................... 6 2.1. Quantitative description of lip static visemes ........................................ 6 2.2. Analysis of static tongue visemes of the Chinese Shaanxi Xi’an Dialect ...................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 3 Dynamic Modeling of the Chinese Shaanxi Xi’an Dialect Speech ....... 11 3.1. The interaction between phonemes and the corresponding lip shape ... 11 3.2. Dynamic tongue viseme classification ................................................. 12 3.3. Results of face animation on the Chinese Shaanxi Xi’an Dialect talking head ........................................................................................................... -

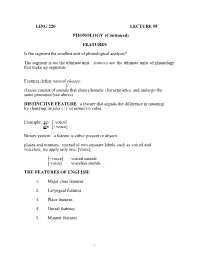

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is The

LING 220 LECTURE #8 PHONOLOGY (Continued) FEATURES Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? The segment is not the ultimate unit: features are the ultimate units of phonology that make up segments. Features define natural classes: ↓ classes consist of sounds that share phonetic characteristics, and undergo the same processes (see above). DISTINCTIVE FEATURE: a feature that signals the difference in meaning by changing its plus (+) or minus (-) value. Example: tip [-voice] dip [+voice] Binary system: a feature is either present or absent. pluses and minuses: instead of two separate labels, such as voiced and voiceless, we apply only one: [voice] [+voice] voiced sounds [-voice] voiceless sounds THE FEATURES OF ENGLISH: 1. Major class features 2. Laryngeal features 3. Place features 4. Dorsal features 5. Manner features 1 1. MAJOR CLASS FEATURES: they distinguish between consonants, glides, and vowels. obstruents, nasals and liquids (Obstruents: oral stops, fricatives and affricates) [consonantal]: sounds produced with a major obstruction in the oral tract obstruents, liquids and nasals are [+consonantal] [syllabic]:a feature that characterizes vowels and syllabic liquids and nasals [sonorant]: a feature that refers to the resonant quality of the sound. vowels, glides, liquids and nasals are [+sonorant] STUDY Table 3.30 on p. 89. 2. LARYNGEAL FEATURES: they represent the states of the glottis. [voice] voiced sounds: [+voice] voiceless sounds: [-voice] [spread glottis] ([SG]): this feature distinguishes between aspirated and unaspirated consonants. aspirated consonants: [+SG] unaspirated consonants: [-SG] [constricted glottis] ([CG]): sounds made with the glottis closed. glottal stop [÷]: [+CG] 2 3. PLACE FEATURES: they refer to the place of articulation. -

78. 78. Nasal Harmony Nasal Harmony

Bibliographic Details The Blackwell Companion to Phonology Edited by: Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice eISBN: 9781405184236 Print publication date: 2011 78. Nasal Harmony RACHEL WWALKER Subject Theoretical Linguistics » Phonology DOI: 10.1111/b.9781405184236.2011.00080.x Sections 1 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments 2 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with transparent segments 3 Nasal consonant harmony 4 Directionality 5 Conclusion ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Notes REFERENCES Nasal harmony refers to phonological patterns where nasalization is transmitted in long-distance fashion. The long-distance nature of nasal harmony can be met by the transmission of nasalization either to a series of segments or to a non-adjacent segment. Nasal harmony usually occurs within words or a smaller domain, either morphologically or prosodically defined. This chapter introduces the chief characteristics of nasal harmony patterns with exemplification, and highlights related theoretical themes. It focuses primarily on the different roles that segments can play in nasal harmony, and the typological properties to which they give rise. The following terminological conventions will be assumed. A trigger is a segment that initiates nasal harmony. A target is a segment that undergoes harmony. An opaque segment or blocker halts nasal harmony. A transparent segment is one that does not display nasalization within a span of nasal harmony, but does not halt harmony from transmitting beyond it. Three broad categories of nasal harmony are considered in this chapter. They are (i) nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments, (ii) nasal vowel– consonant harmony with transparent segments, and (iii) nasal consonant harmony. Each of these groups of systems show characteristic hallmarks. -

Looking Into Segments Sharon Inkelas and Stephanie S Shih University of California, Berkeley & University of California, Merced

Looking into Segments Sharon Inkelas and Stephanie S Shih University of California, Berkeley & University of California, Merced 1 Introduction It is well-known that the phonological ‘segment’ (consonant, vowel) is internally dynamic. Complex segments, such as affricates or prenasalized stops, have sequenced internal phases; coarticulation induces change over time even within apparently uniform segments. Autosegmental Phonology (e.g., Goldsmith 1976, Sagey 1986) captured the internal phasing of complex segments using feature values ordered sequentially on a given tier and ‘linked’ to the same timing unit. Articulatory Phonology (e.g., Browman & Goldstein 1992, Gafos 2002, Goldstein et al. 2009) captures internal phases through the use of coordinated gestures, which overlap in time with one another but are aligned to temporal landmarks. Segments can be internally dynamic in a contrastive way. Affricates differ from plain stops or plain fricatives in being sequentially complex; the same difference obtains between prenasalized vs. plain stops, between contour and level tones, and so forth. Segments can also be dynamic in a noncontrastive way, due to coarticulation with surrounding segments. To the extent that phonological patterns are sensitive to contrastive or noncontrastive segment-internal phasing, the phasing needs to be represented in a manner that is legible to phonological grammar. However, contemporary phonological analysis couched in Optimality Theory, Harmonic Grammar and similar approaches is very highly segment-oriented. For example, Agreement by Correspondence theory, or ABC (Hansson 2001, 2010; Rose & Walker 2004; Bennett 2013; inter alia) and other surface correspondence theories of harmony and disharmony are theories of segmental correspondence. The constraints in these theories refer to segments as featurally uniform units, and do not have a way of referencing their internal phases. -

UC Berkeley Phonlab Annual Report

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title Turbulence & Phonology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4kp306rx Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 4(4) ISSN 2768-5047 Authors Ohala, John J Solé, Maria-Josep Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/P74kp306rx eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2008) Turbulence & Phonology John J. Ohala* & Maria-Josep Solé # *Department of Linguistics, University of California, Berkeley [email protected] #Department of English, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain [email protected] In this paper we aim to provide an account of some of the phonological patterns involving turbulent sounds, summarizing material we have published previously and results from other investigators. In addition, we explore the ways in which sounds pattern, combine, and evolve in language and how these patterns can be derived from a few physical and perceptual principles which are independent from language itself (Lindblom 1984, 1990a) and which can be empirically verified (Ohala and Jaeger 1986). This approach should be contrasted with that of mainstream phonological theory (i.e., phonological theory within generative linguistics) which primarily considers sound structure as motivated by ‘formal’ principles or constraints that are specific to language, rather than relevant to other physical or cognitive domains. For this reason, the title of this paper is meant to be ambiguous. The primary sense of it refers to sound patterns in languages involving sounds with turbulence, e.g., fricatives and stops bursts, but a secondary meaning is the metaphorical turbulence in the practice of phonology over the past several decades. -

Determining the Temporal Interval of Segments with the Help of F0 Contours

Determining the temporal interval of segments with the help of F0 contours Yi Xu University College London, London, UK and Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, Connecticut Fang Liu Department of Linguistics, University of Chicago Abbreviated Title: Temporal interval of segments Corresponding author: Yi Xu University College London Wolfson House 4 Stephenson Way London, NW1 2HE UK Telephone: +44 (0) 20 7679 5011 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7388 0752 E-mail: [email protected] Xu and Liu Temporal interval of segments Abstract The temporal interval of a segment such as a vowel or a consonant, which is essential for understanding coarticulation, is conventionally, though largely implicitly, defined as the time period during which the most characteristic acoustic patterns of the segment are to be found. We report here evidence for a need to reconsider this kind of definition. In two experiments, we compared the relative timing of approximants and nasals by using F0 turning points as time reference, taking advantage of the recent findings of consistent F0-segment alignment in various languages. We obtained from Mandarin and English tone- and focus-related F0 alignments in syllables with initial [j], [w] and [®], and compared them with F0 alignments in syllables with initial [n] and [m]. The results indicate that (A) the onsets of formant movements toward consonant places of articulation are temporally equivalent in initial approximants and initial nasals, and (B) the offsets of formant movements toward the approximant place of articulation are later than the nasal murmur onset but earlier than the nasal murmur offset. In light of the Target Approximation (TA) model originally developed for tone and intonation (Xu & Wang, 2001), we interpreted the findings as evidence in support of redefining the temporal interval of a segment as the time period during which the target of the segment is being approached, where the target is the optimal form of the segment in terms of articulatory state and/or acoustic correlates. -

Factors in Word Duration and Patterns of Segment Duration in Word-Initial and Word- Final Consonant Clusters 1. Introduction

Factors in Word Duration and Patterns of Segment Duration in Word-initial and Word- final Consonant Clusters Becca Schwarzlose 1. Introduction The words playing and splaying have many apparent similarities. In fact, they appear to be identical except that one of the words has an additional segment (/s/) in the first syllable. Therefore, one might expect the duration of the word splaying in a normal utterance to differ from the duration of the word playing only by the duration of /s/. We will call this line of reasoning the Additive Theory of Word Duration because it predicts that as one adds additional segments to a word (such as the progression from laying to playing to splaying), the durations of the individual segments remain stable and the durations of the words increase by the amount of time required for the new segment. We can think of this theory in terms of a stack of blocks. If you have a stack of blocks with a total height h and you add a block of height x to the stack, then the resulting pile will have a total height h + x. The addition of the new block has not changed the heights of the blocks that were already in the stack. Another possible view of word duration offers very different predictions for such circumstances. According to this theory, speakers want to produce words that are isochronous. That is, they want their words to have equal durations. We will call this theory the Isochronal Theory of Word Duration. An important aspect of this theory is the necessary reduction of segment duration. -

Arnold, A. Pronouncing Three-Segment Final Consonant Clusters: a Case Study with Arabic Speakers Learning English (2010)

Arnold, A. Pronouncing Three-Segment Final Consonant Clusters: A Case Study with Arabic Speakers Learning English (2010) The purpose of this study is to determine whether or not pronunciation training results in a decreased use of the following consonant cluster simplification strategies--articulatory feature change, consonant cluster reduction and substitution--when pronouncing words containing final three-segment consonant clusters. This case study involves three Arabic speaking siblings living in Kuwait who received six weeks of pronunciation training. The instructional method incorporated native English speaker modeling, choral repetition, and self-correction using the subjects’ audio taped recordings of them reading the target words in word lists, sentences, and passages. The subjects’ pre- and post- assessments, as well as their weekly pre- and post-training audio recordings, were analyzed. The results from this study show that pronunciation training yields more target-like pronunciation of final three-segment consonant clusters. PRONOUNCING THREE-SEGMENT FINAL CONSONANT CLUSTERS: A CASE STUDY WITH ARABIC SPEAKERS LEARNING ENGLISH By Anjanette Arnold A capstone submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English as a Second Language Hamline University Saint Paul, Minnesota December 11, 2009 Committee: Anne DeMuth, Primary Advisor Deirdre Bird Kramerer, Secondary Advisor Nicholas Walker, Peer Reviewer i TABLE OF CONTEXTS Chapter One: Introduction……………………………………………………………......1 Chapter Two: