Mediterranean and Paratethys. Facts and Hypotheses of an Oligocene to Miocene Paleogeography (Short Overview)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic

water Review Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic Valentina S. Artamonova 1, Ivan N. Bolotov 2,3,4, Maxim V. Vinarski 4 and Alexander A. Makhrov 1,4,* 1 A. N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Molecular Ecology and Phylogenetics, Northern Arctic Federal University, 163002 Arkhangelsk, Russia; [email protected] 3 Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, 163000 Arkhangelsk, Russia 4 Laboratory of Macroecology & Biogeography of Invertebrates, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of zoogeographic, paleogeographic, and molecular data has shown that the ancestors of many fresh- and brackish-water cold-tolerant hydrobionts of the Mediterranean region and the Danube River basin likely originated in East Asia or Central Asia. The fish genera Gasterosteus, Hucho, Oxynoemacheilus, Salmo, and Schizothorax are examples of these groups among vertebrates, and the genera Magnibursatus (Trematoda), Margaritifera, Potomida, Microcondylaea, Leguminaia, Unio (Mollusca), and Phagocata (Planaria), among invertebrates. There is reason to believe that their ancestors spread to Europe through the Paratethys (or the proto-Paratethys basin that preceded it), where intense speciation took place and new genera of aquatic organisms arose. Some of the forms that originated in the Paratethys colonized the Mediterranean, and overwhelming data indicate that Citation: Artamonova, V.S.; Bolotov, representatives of the genera Salmo, Caspiomyzon, and Ecrobia migrated during the Miocene from I.N.; Vinarski, M.V.; Makhrov, A.A. -

Mesozoic Central Atlantic and Ligurian Tethys1

42. RIFTING AND EARLY DRIFTING: MESOZOIC CENTRAL ATLANTIC AND LIGURIAN TETHYS1 Marcel Lemoine, Institut Dolomieu, 38031 Grenoble Cedex, France ABSTRACT The Leg 76 discovery of Callovian sediments lying above the oldest Atlantic oceanic crust allows us to more closely compare the Central Atlantic with the Mesozoic Ligurian Tethys. As a matter of fact, during the Late Jurassic and Ear- ly Cretaceous, both the young Central Atlantic Ocean and the Ligurian Tethys were segments of the Mesozoic Tethys Ocean lying between Laurasia and Gondwana and linked by the Gibraltar-Maghreb-Sicilia transform zone. If we as- sume that the Apulian-Adriatic continental bloc (or Adria) was then a northern promontory of Africa, then the predrift and early drift evolutions of both these oceanic segments must have been roughly the same: their kinematic evolution was governed by the east-west left-lateral motion of Gondwana (including Africa and Adria) relative to Laurasia (in- cluding North America, Iberia, and Europe), at least before the middle Cretaceous (=100 Ma). By the middle Cretaceous, opening of the North Atlantic Ocean led to a drastic change of the relative motions between Africa-Adria and Europe-Iberia. From this time on, closure of the Ligurian segment of the Tethys began, whereas the Central Atlan- tic went on spreading. In fact, field data from the Alps, Corsica, and the Apennines show evidence of a Triassic-Jurassic-Early Cretaceous paleotectonic evolution rather comparable with that of the Central Atlantic. Rifting may have been started during the Triassic (at least the late Triassic) but reached its climax in the Liassic. -

Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas

Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA BASINS Main seas, straits and gulfs in the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, together with locations mentioned in the text for the distribution of marine mammals and sea turtles Ukraine Russia SEA OF AZOV Kerch Strait Crimea Romania Georgia Slovenia France Croatia BLACK SEA Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Monaco Bosphorus LIGURIAN SEA Montenegro Strait Pelagos Sanctuary Gulf of Italy Lion ADRIATIC SEA Albania Corsica Drini Bay Spain Dardanelles Strait Greece BALEARIC SEA Turkey Sardinia Algerian- TYRRHENIAN SEA AEGEAN SEA Balearic Islands Provençal IONIAN SEA Syria Basin Strait of Sicily Cyprus Strait of Sicily Gibraltar ALBORAN SEA Hellenic Trench Lebanon Tunisia Malta LEVANTINE SEA Israel Algeria West Morocco Bank Tunisian Plateau/Gulf of SirteMEDITERRANEAN SEA Gaza Strip Jordan Suez Canal Egypt Gulf of Sirte Libya RED SEA Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas Compiled by María del Mar Otero and Michela Conigliaro The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by Compiled by María del Mar Otero IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain © IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Malaga, Spain Michela Conigliaro IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Copyright © 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources With the support of Catherine Numa IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Annabelle Cuttelod IUCN Species Programme, United Kingdom Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the sources are fully acknowledged. -

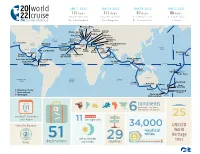

World Cruise - 2022 Use the Down Arrow from a Form Field

This document contains both information and form fields. To read information, World Cruise - 2022 use the Down Arrow from a form field. 20 world JAN 5, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 5, 2022 111 days 111 days 97 days 88 days 22 cruise roundtrip from roundtrip from Los Angeles to Ft. Lauderdale Ft. Lauderdale Los Angeles Ft. Lauderdale to Rome Florence/Pisa (Livorno) Genoa Rome (Civitavecchia) Catania Monte Carlo (Sicily) MONACO ITALY Naples Marseille Mykonos FRANCE GREECE Kusadasi PORTUGAL Atlantic Barcelona Heraklion Ocean SPAIN (Crete) Los Angeles Lisbon TURKEY UNITED Bermuda Ceuta Jerusalem/Bethlehem STATES (West End) (Spanish Morocco) Seville (Ashdod) ine (Cadiz) ISRAEL Athens e JORDAN Dubai Agadir (Piraeus) Aqaba Pacific MEXICO Madeira UNITED ARAB Ocean MOROCCO l Dat L (Funchal) Malta EMIRATES Ft. Lauderdale CANARY (Valletta) Suez Abu ISLANDS Canal Honolulu Huatulco Dhabi ne inn Puerto Santa Cruz Lanzarote OMAN a a Hawaii r o Hilo Vallarta NICARAGUA (Arrecife) de Tenerife Salãlah t t Kuala Lumpur I San Juan del Sur Cartagena (Port Kelang) Costa Rica COLOMBIA Sri Lanka PANAMA (Puntarenas) Equator (Colombo) Singapore Equator Panama Canal MALAYSIA INDONESIA Bali SAMOA (Benoa) AMERICAN Apia SAMOA Pago Pago AUSTRALIA South Pacific South Indian Ocean Atlantic Ocean Ocean Perth Auckland (Fremantle) Adelaide Sydney New Plymouth Burnie Picton Departure Ports Tasmania Christchurch More Ashore (Lyttelton) Overnight Fiordland NEW National Park ZEALAND up to continentscontinents (North America, South America, 111 51 Australia, Europe, Africa -

1219421 the Opening of Neo-Tethys and the Formation of the Khuff Passive Margin

1219421 The Opening of Neo-Tethys and the Formation of the Khuff Passive Margin 1219421 The Opening of Neo-Tethys and the Formation of the Khuff Passive Margin *1 2 Bell, Andrew ; Spaak, Pieter (1) Shell Global Solutions International BV, Rijswijk, Netherlands. (2) Shell International Exporation and Production BV, The Hague, Netherlands. Any investigation of regional geology and palaeomagnetism in the Middle East will show that in the Permian, a series of terranes separated from Gondwana and drifted north, opening the Neo-Tethys Ocean in their wake. To the north of these terranes, the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean closed and was largely subducted. Eventually in a non-synchronous movement but largely in late Triassic and early Jurassic times, these terranes docked with the northern margin of the former Palaeo- Tethys during the Cimmerian Orogeny. The opening of the Neo-Tethys in Arabia does not follow the classic pattern of continental break-up resulting in oceanic crust. Classically we should expect thermal up-doming, followed by the onset of syn-rift deposition, frequently but not always associated with volcanism. The formation of en-echelon systems of rotated fault blocks are also characteristic, followed by a break-up unconformity and the formation of the first oceanic crust. What we see in Arabia as a consequence of the opening of Neo-Tethys exhibits few of these features. Distinguishing thermal up-doming from the uplift associated with the ‘Hercynian’ event in Arabia, coupled with the glacial sculpting of the Permo-Carboniferous Unayzah Formation is fraught with difficulty. Although locally volcanics of Permian age are known from Oman, they are absent over most of Arabia. -

Ecosystems Mario V

Ecosystems Mario V. Balzan, Abed El Rahman Hassoun, Najet Aroua, Virginie Baldy, Magda Bou Dagher, Cristina Branquinho, Jean-Claude Dutay, Monia El Bour, Frédéric Médail, Meryem Mojtahid, et al. To cite this version: Mario V. Balzan, Abed El Rahman Hassoun, Najet Aroua, Virginie Baldy, Magda Bou Dagher, et al.. Ecosystems. Cramer W, Guiot J, Marini K. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin -Current Situation and Risks for the Future, Union for the Mediterranean, Plan Bleu, UNEP/MAP, Marseille, France, pp.323-468, 2021, ISBN: 978-2-9577416-0-1. hal-03210122 HAL Id: hal-03210122 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03210122 Submitted on 28 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin – Current Situation and Risks for the Future First Mediterranean Assessment Report (MAR1) Chapter 4 Ecosystems Coordinating Lead Authors: Mario V. Balzan (Malta), Abed El Rahman Hassoun (Lebanon) Lead Authors: Najet Aroua (Algeria), Virginie Baldy (France), Magda Bou Dagher (Lebanon), Cristina Branquinho (Portugal), Jean-Claude Dutay (France), Monia El Bour (Tunisia), Frédéric Médail (France), Meryem Mojtahid (Morocco/France), Alejandra Morán-Ordóñez (Spain), Pier Paolo Roggero (Italy), Sergio Rossi Heras (Italy), Bertrand Schatz (France), Ioannis N. -

Coevolution of Global Brachiopod Palaeobiogeography and Tectonopalaeogeography During the Carboniferous Ning Li1,2*, Cheng-Wen Wang1, Pu Zong3 and Yong-Qin Mao4

Li et al. Journal of Palaeogeography (2021) 10:18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s42501-021-00095-z Journal of Palaeogeography ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Coevolution of global brachiopod palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography during the Carboniferous Ning Li1,2*, Cheng-Wen Wang1, Pu Zong3 and Yong-Qin Mao4 Abstract The global brachiopod palaeobiogeography of the Mississippian is divided into three realms, six regions, and eight provinces, while that of the Pennsylvanian is divided into three realms, six regions, and nine provinces. On this basis, we examined coevolutionary relationships between brachiopod palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography using a comparative approach spanning the Carboniferous. The appearance of the Boreal Realm in the Mississippian was closely related to movements of the northern plates into middle–high latitudes. From the Mississippian to the Pennsylvanian, the palaeobiogeography of Australia transitioned from the Tethys Realm to the Gondwana Realm, which is related to the southward movement of eastern Gondwana from middle to high southern latitudes. The transition of the Yukon–Pechora area from the Tethys Realm to the Boreal Realm was associated with the northward movement of Laurussia, whose northern margin entered middle–high northern latitudes then. The formation of the six palaeobiogeographic regions of Mississippian and Pennsylvanian brachiopods was directly related to “continental barriers”, which resulted in the geographical isolation of each region. The barriers resulted from the configurations of Siberia, Gondwana, and Laurussia, which supported the Boreal, Tethys, and Gondwana realms, respectively. During the late Late Devonian–Early Mississippian, the Rheic seaway closed and North America (from Laurussia) joined with South America and Africa (from Gondwana), such that the function of “continental barriers” was strengthened and the differentiation of eastern and western regions of the Tethys Realm became more distinct. -

Wave Energy in the Balearic Sea. Evolution from a 29 Year Spectral Wave Hindcast

1 Wave energy in the Balearic Sea. Evolution from a 29 2 year spectral wave hindcast a b,∗ c 3 S. Ponce de Le´on , A. Orfila , G. Simarro a 4 UCD School of Mathematical Sciences. Dublin 4, Ireland b 5 IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB). 07190 Esporles, Spain. c 6 Institut de Ci´enciesdel Mar (CSIC). 08003 Barcelona, Spain. 7 Abstract 8 This work studies the wave energy availability in the Western Mediterranean 9 Sea using wave simulation from January 1983 to December 2011. The model 10 implemented is the WAM, forced by the ECMWF ERA-Interim wind fields. 11 The Advanced Scatterometer (ASCAT) data from MetOp satellite and the 12 TOPEX-Poseidon altimetry data are used to assess the quality of the wind 13 fields and WAM results respectively. Results from the hindcast are the 14 starting point to analyse the potentiality of obtaining wave energy around 15 the Balearic Islands Archipelago. The comparison of the 29 year hindcast 16 against wave buoys located in Western, Central and Eastern basins shows a 17 high correlation between the hindcasted and the measured significant wave 18 height (Hs), indicating a proper representation of spatial and temporal vari- 19 ability of Hs. It is found that the energy flux at the Balearic coasts range 20 from 9:1 kW=m, in the north of Menorca Island, to 2:5 kW=m in the vicinity 21 of the Bay of Palma. The energy flux is around 5 and 6 times lower in 22 summer as compared to winter. 23 Keywords: Mediterranean Sea, WAM model, wave energy, wave climate 24 variability, ASCAT, TOPEX-Poseidon ∗Corresponding author PreprintEmail submitted address: [email protected] Elsevier(A. -

A Reconstruction of Iberia Accounting for Western Tethys–North Atlantic Kinematics Since the Late-Permian–Triassic

Solid Earth, 11, 1313–1332, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/se-11-1313-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. A reconstruction of Iberia accounting for Western Tethys–North Atlantic kinematics since the late-Permian–Triassic Paul Angrand1, Frédéric Mouthereau1, Emmanuel Masini2,3, and Riccardo Asti4 1Geosciences Environnement Toulouse (GET), Université de Toulouse, UPS, Univ. Paul Sabatier, CNRS, IRD, 14 av. Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France 2M&U sas, 38120 Saint-Égrève, France 3ISTerre, Université Grenoble Alpes, 38000 Grenoble, France 4Université de Rennes, CNRS, Géosciences Rennes-UMR 6118, 35000 Rennes, France Correspondence: Paul Angrand ([email protected]) Received: 20 February 2020 – Discussion started: 6 March 2020 Revised: 12 May 2020 – Accepted: 27 May 2020 – Published: 21 July 2020 Abstract. The western European kinematic evolution results 1 Introduction from the opening of the western Neotethys and the Atlantic oceans since the late Paleozoic and the Mesozoic. Geolog- Global plate tectonic reconstructions are mostly based on the ical evidence shows that the Iberian domain recorded the knowledge and reliability of magnetic anomalies that record propagation of these two oceanic systems well and is there- age, rate, and direction of sea-floor spreading (Stampfli and fore a key to significantly advancing our understanding of Borel, 2002; Müller et al., 2008; Seton et al., 2012). Where the regional plate reconstructions. The late-Permian–Triassic these constraints are lacking or their recognition is ambigu- Iberian rift basins have accommodated extension, but this ous, kinematic reconstructions rely on the description and in- tectonic stage is often neglected in most plate kinematic terpretation of the structural, sedimentary, igneous and meta- models, leading to the overestimation of the movements be- morphic rocks of rifted margins and orogens (e.g., Handy tween Iberia and Europe during the subsequent Mesozoic et al., 2010; McQuarrie and Van Hinsbergen, 2013). -

THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS of the BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation

THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA A brief introduction What are marine protected areas? Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are portions of the marine The level of protection of the Balearic Islands’ MPAs varies environment, sometimes connected to the coast, under depending on the legal status and the corresponding some form of legal protection. MPAs are used globally as administrations. In the Balearic Islands we find MPAs in tools for the regeneration of marine ecosystems, with the inland waters that are the responsibility of the Balearic dual objective of increasing the productivity of fisheries Islands government and island governments (Consells), and resources and conserving marine habitats and species. in external waters that depend on the Spanish government. Inland waters are those that remain within the polygon We define MPAs as those where industrial or semi-indus- marked by the drawing of straight lines between the capes trial fisheries (trawling, purse seining and surface longlining) of each island. External waters are those outside. are prohibited or severely regulated, and where artisanal and recreational fisheries are subject to regulation. Figure 1. Map of the Balearic Islands showing the location of the marine protection designations. In this study we consider all of them as marine protected areas except for the Natura 2000 Network and Biosphere Reserve areas. Note: the geographical areas of some protection designations overlap. THE MARINE PROTECTED AREAS OF THE BALEARIC SEA Marilles Foundation Table 1. Description of the different marine protected areas of the Balearic Islands and their fishing restrictions. -

SESSION I : Geographical Names and Sea Names

The 14th International Seminar on Sea Names Geography, Sea Names, and Undersea Feature Names Types of the International Standardization of Sea Names: Some Clues for the Name East Sea* Sungjae Choo (Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Kyung-Hee University Seoul 130-701, KOREA E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract : This study aims to categorize and analyze internationally standardized sea names based on their origins. Especially noting the cases of sea names using country names and dual naming of seas, it draws some implications for complementing logics for the name East Sea. Of the 110 names for 98 bodies of water listed in the book titled Limits of Oceans and Seas, the most prevalent cases are named after adjacent geographical features; followed by commemorative names after persons, directions, and characteristics of seas. These international practices of naming seas are contrary to Japan's argument for the principle of using the name of archipelago or peninsula. There are several cases of using a single name of country in naming a sea bordering more than two countries, with no serious disputes. This implies that a specific focus should be given to peculiar situation that the name East Sea contains, rather than the negative side of using single country name. In order to strengthen the logic for justifying dual naming, it is suggested, an appropriate reference should be made to the three newly adopted cases of dual names, in the respects of the history of the surrounding region and the names, people's perception, power structure of the relevant countries, and the process of the standardization of dual names. -

49. GENESIS of the TETHYS and the MEDITERRANEAN Kenneth J

49. GENESIS OF THE TETHYS AND THE MEDITERRANEAN Kenneth J. Hsü, Geologisches Institut, ETH Zurich, Switzerland and Daniel Bernoulli, Geologisch-Palàontologisches Institut, Universitàt Basel, Switzerland ABSTRACT The Triassic Paleotethys was a wedge-like ocean opening to the east, which was totally eliminated during the early Mesozoic by subduction along the Cimmerian and Indosinian suture zone. The Tethys, s.s., was an Early Jurassic creation formed when Africa moved east relative to Europe. The sinistral movement of Africa continued until Late Cretaceous when the movement became dextral. The closing of the gap between Africa and Europe led to the Alpine orogeny and the elimination of much of the Tethys. Only the eastern Mediterranean Ionian and Levantine basins are left as possible relics of this Mesozoic ocean. The western Mediter- ranean and the Aegean are post-orogenic basins. The Balearic Ba- sin was created during late Oligocene or earliest Miocene time by rifting tectonics. The Tyrrhenian Basin was probably somewhat younger. The presence of oceanic tholeiites under its abyssal plain indicates that submarine basalt volcanism played a major role in the genesis of this basin. The Aegean Basin is probably the youngest and has undergone considerable Pliocene-Quaternary subsidence. Tectonic synthesis indicates that the Mediterranean basins, ex- cept perhaps the Aegean, were in existence and deep prior to the Messinian Salinity Crisis. FOREWORD nent Gondwana was the home of the late Paleozoic Glossopteria flora. Its inclusion in the definition of Several attempts have been made to reconstruct the Tethys seemed to imply the existence of this mediterra- tectonic history of the Tethys and its descendent, the nean during the Paleozoic.