Social Semiotics Created in China and Pak Sheung Chuen's Tactics Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

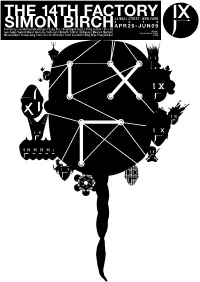

The 14Th Factory

ABOUT THE 14TH FACTORY Entering the world of Simon Birch’s The 14th Factory is to explored both in his paintings (where characters seem to become more than a visitor or a viewer: it is like falling fight their way free of a gravitational pull, wrestling with the into the rabbit hole, transforming into a central player in a medium of the art itself), and in his large-scale installation collaboratively constructed adventure that both embraces projects, most notably HOPE & GLORY (2010), that interlink you and further unfolds through your presence. the artist’s own biography with the rise and fall of mythic and historical pasts. The title The 14th Factory alludes to the historical ‘Thirteen Factories’ (or hongs) of Canton (Guangzhou), China-- In Hong Kong, Birch is inescapably both an insider and an designated trading quarters for Western merchants that outsider, and yet this status gives him a kind of freedom to played an important role in the West’s interactions with move beyond calcified or perceived boundaries. Hong Kong China from the eighteenth century to the First Opium War itself is a kind of nexus of both connectivity and uncertainty, between China and Britain (1849-1842). By decree of the bounded by China and open to the world, poised at a Emperor, the bounded area of the foreign ‘factories’ (an crossroads and re-imagining its own future. From his Hong old word for trading houses) was allowed to exist only Kong base Birch has brought his collaborative energy into outside the main city walls of Canton, thus creating a kind projects -

This Article Is Written As Part of the New Hall Art Collection Asia

Eliza Gluckman and Phoebe Wong The Parallax of Generations and Genders: Women in Art, the Hong Kong Case his article is written as part of the New Hall Art Collection Asia Art Initiative, “Women in Art: Hong Kong,” a research project Tcommissioned in collaboration with the Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, in 2017. The New Hall Art Collection currently boasts over five hundred works, housed at Murray Edwards College of the University of Cambridge, England, and is the largest collection of artworks by women in Europe. Founded in 1954 as New Hall, Murray Edwards College was created to increase educational opportunities for women, and it continues to advocate for equality. Murray Edwards College and the University have a long established relationship with Hong Kong and the development of this project went hand in hand with relationships old and new, leading to the addition of new works in the collection by artists from Hong Kong. In 1992, commentators who were invited to the launch of the New Hall Art Collection wrestled with the deceptively simple but contested term “women artists.” Feminist art historian Griselda Pollock suggested in her published address, “We can read the works for clues about the full complexity and possibility of what it might mean to live ‘as women’ under the sign ‘woman,’ ‘black woman,’ ‘lesbian,’ ‘mother,’ ‘artist,’ ‘citizen,’ and so forth. Therein in this collection we will find no consistency, no generality, no common thread.”1 And yet commonalities are discussedboth clichés and factsevery time a platform is opened to talk about "women artists," with recurring questions about women’s representation and visibility in art history, public institutions, and the market. -

Download PDF File Format Form

Foreword 2-3 Performance Pledges 4 Vision, Mission & Values 5 Leisure Services 6-28 Cultural Services 29-82 Administration 83-96 Feedback Channels 97 Appendices 98-121 1 Foreword The year 2015-16 was another fruitful one for the LCSD in its efforts to improve the quality of life of Hong Kong and enhance the physical and cultural well-being of people. Providing well-maintained and up-to-date facilities that meet the needs of our community remains our top priority. The Tiu Keng Leng Sports Centre and Public Library was one of the brand-new facilities that came into service during the year. We completed turf reconstruction at the Hong Kong Stadium, and carried out a major renovation of the Hong Kong Space Museum. We also pressed ahead with the upgrading and faceli of the Hong Kong Museum of Art, designed not only to increase the museum's exhibition space but also to enhance its visibility, accessibility, customer orientation and branding. Meanwhile, we were excited to begin construction of the new and much anticipated East Kowloon Cultural Centre. We continued to stage many colourful arts and cultural events during the year. One of the highlights was the first Muse Fest in the summer of 2015, which offered a rich celebration of all 14 museums under the auspices of the LCSD through a wide array of fun-filled activities and enriching experiences for the community. As part of the Appreciate Hong Kong campaign, free admission to museums was offered in the month of January 2016, resulting in an increase of over 40% in the number of visitors when compared with that in January 2015. -

The Tree Museum 2007 Preface

2007 The Tree Museum THE TENTH ANNUAL EXHIBITION SEPTEMBER 16 TO OCTOBER 28 2007 WHAT IS PLACE Site-specific installations by Exhibition curated by ANNE O’CALLAGHAN WEN-CHIH WANG (TAIWAN) JAFFA LAAM LAM (HONG KONG) MICHAEL BELMORE (CANADA) Exhibition essays: E.J. LIGHTMAN (CANADA) NOEL HARDING (CANADA) Transplant MARGARET RODGERS Temporary interventions on site News of Difference: Siting the Tree Museum GIL McELROY by Persona Volare: CARLO CESTA In Through the Outdoors IVAN JURAKIC MICHAEL DAVEY JOHN DICKSON REBECCA DIEDERICHS BRIAN HOBBS LORNA MILLS LISA NEIGHBOUR CHANTAL ROUSSEAU LYLA RYE KATE WILSON JOHANNES ZITS The Tree Museum • Doe Lake Road • Muskoka CONTENTS 4 Preface ANNE O’CALLAGHAN 5 Transplant MARGARET RODGERS 9 News of Difference: Siting the Tree Museum GIL MCELROY 17 In Through the Outdoors IVAN JURAKIC 25 The Road North/The Road South 32 End Notes 35 Biographical Notes 36 Acknowledgements 38 The Tree Museum Exhibition History 1998 to 2007 39 THE TREE MUSEUM 2007 PREFACE THE TREE MUSEUM COLLECTIVE was established in 1997. The next year Badanna Zack, Tim 5 Whiten and Anne O’Callaghan opened the site with the first exhibition, curated by founding member E.J. Lightman. Since 1998, 44 artists have created 54 unique projects relating to the site of The Tree Museum and engaging the complex relationship between humans and nature, includ- ing adoration, reliance and exploitation. In these ten years artists have addressed a wide range of issues such as the urbanization and gentrification of wilderness, the social and natural history of the site, and geopolitics and ownership. Connections with the historical place and the strata making up the past are the starting point for many of the works, notably the systematic documentation of the site’s natural and human- made history by Jocelyne Salem Belcourt (Glimmer, 2000). -

Jaffa Lam Born Hong Kong Lives and Works in Hong Kong Karin Weber

Jaffa Lam Born Hong Kong Lives and Works in Hong Kong Karin Weber Gallery artist Jaffa Lam is a sculptor specializing in large-scale, site-specific, mixed-media sculptures and installations, which are mainly made with recycled materials like crate wood, old furniture and recycled fabric. In recent years, she has been involved in many public art and community projects in Hong Kong and overseas. Her works often explore issues related to local culture, history, society and current affairs. Apart from solo exhibitions, Lam was invited to take part in many local and international exhibitions, as well as artist residency programs in Kenya, Taiwan, Bangladesh, China, United States and Canada. She was awarded the Asian Cultural Council Desiree and Hans Michael Jebsen Fellowship in 2006. Chinese University Hong Kong, BFA, MFA, Education Hong Kong Art School, Senior Lecturer and Program Coordinator, Higher Diploma Fine Art Selected Solo Exhibitions 2015 Crush On My City, Karin Weber Gallery, Hong Kong 2013 One-Minute Glam 2013 ‘Jaffa Lam Collaborative: Weaver’, Setouchi Triennale, Japan 2013 Jaffa Lam Laam Collaborative: Weaver, Pao Gallery, Hong Kong Art Centre, Hong Kong 2011 Micro Economy, School of Art Gallery, RMIT, Melbourne, Australia 2007 Exchange Knowledge, Dinersty Chinese Restaurant, 411 Eighth Avenue, New York City, USA 2005 Travel with Rickshaw, Alliance Francaise, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2005 Exchange. History, White Tube Gallery, Hong Kong 2004 Twins, Pottery Workshop, Shanghai, China 2003 Just for Fun, ARTtube@mtr, Central Station, Hong -

26 August 2021 Press Preview: 9 July 2021, 4 – 6Pm Opening Reception: 10 July 2021, 11Am – 7Pm

Ze/Ro Curated by Shirky Chan 13 July – 26 August 2021 Press Preview: 9 July 2021, 4 – 6pm Opening Reception: 10 July 2021, 11am – 7pm Ben Brown Fine Arts is delighted to announce our forthcoming exhibition Ze/Ro at the Hong Kong gallery, from July through August 2021. The exhibition is organised by Hong Kong-based curator Shirky Chan as part of the Hong Kong Art Gallery Association’s (HKAGA) Summer Programme. Fostering the local arts community with a focus on young talent, the HKAGA’s Summer Programme actively builds a bridge between its member galleries, emerging artists, curators and writers within this vibrant city. Chan has curated a contemplative and topical group show featuring the work of five emerging artists: Au Hoi Lam, Chan Ka Kiu, Christy Chow, Jaffa Lam and Jess Lau. All of these artists are living and working in Hong Kong and each addresses notions of identity, gender, society and self, framed by social constructs and desired dissolutions of gender. Chan explains: Gender is a social construct. Culture and tradition are often used to shape the contents of gender stereotypes to prescribe regulatory social regimes. In this sense, the representation of female and male is still crucial in terms of how they are being projected by self and others in society. To enact gender neutrality and de-gendering in society, Oxford English Dictionary has officially adopted the new gender pronoun “Ze” instead of “He” and “She” to represent non-binary gender identities. As such, the powerful and divine word “Hero” is no longer the privilege of “He” in the world of linguistics and reality. -

JAFFA LAM LAAM B. 1973, Hong Kong Lives and Works in Hong Kong

JAFFA LAM LAAM b. 1973, Hong Kong Lives and works in Hong Kong EDUCATION 1999-2000 PhD, Fine Arts, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 1997-1999 MFA, Fine Arts, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 1993-1997 BFA, Fine Arts, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SOLO EXHIBITIONS AND PRESENTATIONS 2018 Piu3, Shouson Theatre, Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong 2017 Jaffa Lam X Sam Tung Uk, Sam Tung Uk Museum, Hong Kong 2015 Looking for my family story, Lumenvisum Gallery, Hong Kong 2013 Jaffa Lam Laam Collaborative: Weaver, Pao Galleries, Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong 2011 Micro Economy, RMIT School of Art Gallery, Melbourne, Australia 2005 Travel with Rickshaw, Alliance Française, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2003 Murmur, Shatin Town Hall, Yuen Long Theatre, Hong Kong SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2019 2019 Kai Hua Temple International Art Festival, Gao Ping, Shang Xi, China 2018 Heimat - The 2018 Guang’an Field Art Biennale, Wusheng Bao Zhen Sai, Guang An, China Fete Des Lumieres, Lyon, France Hong Kong Arts Centre 40th Anniversary Flagship Exhibition: Wanchai Grammatica: Past, Present, Future Tense, Pao Gallery, Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong A Beast, A God, And A Line, Parasite Art Space, Hong Kong, Hong Kong; Pyinsa Rasa Art, Space at The Secretariat & Myanna/art Gallery, Yangon, Myanmar; Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland Manifesta 12, The European Nomadic Biennial, Palermo, Italy 2017 Lumieres Hong Kong, Edinburgh Place, Central, Hong Kong 2016 Art Safietal, Land Art Festival in Safiental Valley, Switzerland -

An Art Teacher in China: the 18Th Biennale of Sydney at Cockatoo

an art teacher in China: The 18th Biennale of Sydney at Cockato... http://anartteacherinchina.blogspot.ca/2012/07/18th-biennale-of... Share 0 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In an art teacher in China Musings about China, Chinese art and art education by an Australian art teacher A continuing diary about my travels in China, and thoughts about China and Chinese art from home and abroad Wednesday, July 11, 2012 Facebook Share The 18th Biennale of Sydney at Cockatoo Island - mist, mystery and even some Share magic 1 Subscribe To Posts Comments Follow by Email 1 of 6 13-01-10 12:43 PM an art teacher in China: The 18th Biennale of Sydney at Cockato... http://anartteacherinchina.blogspot.ca/2012/07/18th-biennale-of... Email address... Submit Labels Liu Zhuoquan learning Chinese Gao Ping Shi Zhi Ying White Rabbit Chen Hangfeng Gao Rong Hu Qinwu Huang Yong Ping Carol Lee Mei-kuen Chu Haina Jin Sha Li Jin Liang Yuanwei Lin Tianmiao Ray Hughes Gallery Shi Qing Wu Meng Yang Zhenzong 'The Art Life' 18th Biennale of Sydney Chang Xugong Cui Guotai Dong Installation View 'Source', Ed Pien with Tanya Tagiq, Cockatoo Island, 18th Biennale of Sydney Yuan Hanison Hok Shing Lau Jaffa Lam I spent a cold winter's day wandering all over Cockatoo Island seeking out the works Jin Nu Lam Tung-pang Li Tingting Liu that I thought would be the most interesting / engaging / beautiful / exciting. Initially I Xiaodong Luo Brothers Monika Lin Pu was a little underwhelmed by Fujiko Nakaya's 'Fog' installation, first encountering it Jie Red Gate Gallery Shen Shaomin from the top of the hill and looking down into the crevice from which the clouds of Three Shadows Yao Lu Zhou Siwei song mist emerge. -

藝術家的百種執迷 111 Artists Reveal Their Obsessions!

新聞稿 - 請即時公佈 / PRESS RELEASE – For Immediate Release PREOCCUPATIONS: THINGS ARTISTS DO ANYWAY 2008 年 6 月 30 日,香港 / June 30, 2008, Hong Kong 藝術家的百種執迷 111 Artists Reveal Their Obsessions! Preoccupations: Things Artists Do Anyway 泥人和李鴻輝的最新書作 / A bookwork by Cornelia Erdmann & Michael Lee 出版發布會 / Publication Launch Kubrick 咖啡店 / Kubrick Bookshop Café 2008 年 7 月 19 日(星期六)/ Saturday, 19th of July 2008 下午三時正 至 四時三十分 / 3–4.30pm 由藝術家泥人和李鴻輝攜手編撰、泥人 laiyanPROJECTS 及 Studio Bibliothèque 協作出版的書作 「Preoccupations: Things Artists Do Anyway」向讀者揭示藝術家在創作以外的執迷。書籍出版發布會謹訂於 2008 年 7 月 19 日(星期六)下午三時正至四時三十分假座 Kubrick 咖啡店舉行。 Preoccupations: Things Artists Do Anyway is a bookwork that explores the preoccupations of artists when they are not making art. It is conceived, compiled and edited by artists Cornelia Erdmann and Michael Lee Hong Hwee, jointly published by 泥人 laiyanPROJECTS and Studio Bibliothèque, and will be launched on Sat, 19 Jul 2008, 3 - 4.30pm, at Kubrick Bookshop Café. 翻閱英語字典,preoccupation 可解讀作讓人凝神貫注、全情投入的狀態、意念、感覺、物件、人物、地點、 活動或事情,既可指奮發圖強,也可以是不能自拔的表現。這樣的沉迷見於可舒緩壓力的嗜好、無限擴充的收 藏品、縈懷不滅的夢境、沉溺斷腸的感情、莫名興奮的戀物癖、甚至是無可救藥的強迫症。111 名從事視藝、 文學、表演、電影、設計、建築創作的藝術家,以文字和圖象,在書中反思他們日常生活中從心而發、樂此不 疲、甘心排除萬難的百種執迷。讀者可一邊細嚼其中的散文、詩句、日記、宣言、哲理、故事、說明和書信, 一邊窺視他們的照片、速寫、插圖、圖表和電腦螢幕定格。精選篇章包括: By definition, a ‘preoccupation’ is a state, condition, idea, feeling, object, person, place, activity or event on which a person expends extended time and energy, whether purposefully or helplessly. It may be a leisure activity that eases the tedium of work, a collection of things that one cannot stop expanding, a dream that one has frequently, a person to whom one is powerlessly connected, a fetish object that titillates one’s sexual desires, or a obsessive-compulsive disorder beyond control. -

Women in Art, the Hong Kong Case

Eliza Gluckman and Phoebe Wong The Parallax of Generations and Genders: Women in Art, the Hong Kong Case his article is written as part of the New Hall Art Collection Asia Art Initiative, “Women in Art: Hong Kong,” a research project Tcommissioned in collaboration with the Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, in 2017. The New Hall Art Collection currently boasts over five hundred works, housed at Murray Edwards College of the University of Cambridge, England, and is the largest collection of artworks by women in Europe. Founded in 1954 as New Hall, Murray Edwards College was created to increase educational opportunities for women, and it continues to advocate for equality. Murray Edwards College and the University have a long established relationship with Hong Kong and the development of this project went hand in hand with relationships old and new, leading to the addition of new works in the collection by artists from Hong Kong. In 1992, commentators who were invited to the launch of the New Hall Art Collection wrestled with the deceptively simple but contested term “women artists.” Feminist art historian Griselda Pollock suggested in her published address, “We can read the works for clues about the full complexity and possibility of what it might mean to live ‘as women’ under the sign ‘woman,’ ‘black woman,’ ‘lesbian,’ ‘mother,’ ‘artist,’ ‘citizen,’ and so forth. Therein in this collection we will find no consistency, no generality, no common thread.”1 And yet commonalities are discussedboth clichés and factsevery time a platform is opened to talk about "women artists," with recurring questions about women’s representation and visibility in art history, public institutions, and the market. -

RMIT Gallery Exhibition Report 2008 7 8

RMIT Gallery Exhibition Report 2008 WWW.RMIT.EDU.AU/RMITGALLERY 7 8 1 11 February–22 March Zandra Rhodes A Life Long a complex paper structure from geometric forms, lit from above with a stark Love Affair with Textiles Fashion doyenne Zandra Rhodes’s white light. Part of the 2008 Melbourne State of Design Festival. designs are displayed in the first major retrospective in Australia. Rhodes Public 18 July, Grace Tan and Peter Sim, artist talk. began as a textile designer in the UK in the late ’60s and remains one of Program the most creative and influential artists in the fashion world today. Her 11 July–23 August Klaus Rinke Recent Drawings RHINE flamboyant use of colour, form and elements from traditional costumes • RUHR • LOIRE • DANUBE • PACIFIC CONNECTION • RE-AUSTRALIA around the world has led to original clothing that is innovative and timeless. Rover Thomas Joolama Selected Early Paintings This exhibition charts Rhodes’s creative progress from the initial inspiration Leading German artist Klaus Rinke visited the Australian desert in the late to the finished product. Fifty original garments and textiles are presented ’70s and drew strong parallels of land, spirit and place. This and subsequent alongside her inspirational sketchbooks, hand-printed fabrics and paper visits led to his massive Australian Diary, a collection of 800 drawings. His patterns. Part of the 2008 L’Oréal Melbourne Fashion Festival Cultural profound experience was the recognition in Indigenous artwork of what he Program. Curated by Suzanne Davies and Sarah Morris. Public called abstract thinking; this was to give him a way out of the gap between Program 4 March, Zandra Rhodes, RMIT University School of Art Forum.