The Horror and the Glory: Bomber Command in British Memories Since 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M. Strohn: the German Army and the Defence of the Reich

Matthias Strohn. The German Army and the Defence of the Reich: Military Doctrine and the Conduct of the Defensive Battle 1918–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 292 S. ISBN 978-0-521-19199-9. Reviewed by Brendan Murphy Published on H-Soz-u-Kult (November, 2013) This book, a revised version of Matthias political isolation to cooperation in military mat‐ Strohn’s Oxford D.Phil dissertation is a reap‐ ters. These shifts were necessary decisions, as for praisal of German military thought between the ‘the Reichswehr and the Wehrmacht in the early World Wars. Its primary subjects are political and stages of its existence, the core business was to military elites, their debates over the structure find out how the Fatherland could be defended and purpose of the Weimar military, the events against superior enemies’ (p. 3). that shaped or punctuated those debates, and the This shift from offensive to defensive put the official documents generated at the highest levels. Army’s structural subordination to the govern‐ All of the personalities, institutions and schools of ment into practice, and shocked its intellectual thought involved had to deal with a foundational culture into a keener appreciation of facts. To‐ truth: that any likely adversary could destroy ward this end, the author tracks a long and wind‐ their Army and occupy key regions of the country ing road toward the genesis of ‘Heeresdien‐ in short order, so the military’s tradition role was stvorschrfift 300. Truppenführung’, written by doomed to failure. Ludwig Beck and published in two parts in 1933 The author lays out two problems to be ad‐ and 1934, a document which is widely regarded to dressed. -

Day Fighters in Defence of the Reich : a War Diary, 1942-45 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DAY FIGHTERS IN DEFENCE OF THE REICH : A WAR DIARY, 1942-45 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Donald L. Caldwell | 424 pages | 29 Feb 2012 | Pen & Sword Books Ltd | 9781848325258 | English | Barnsley, United Kingdom Day Fighters in Defence of the Reich : A War Diary, 1942-45 PDF Book Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. A summary of every 8th and 15th US Army Air Force strategic mission over this area in which the Luftwaffe was encountered. You must have JavaScript enabled in your browser to utilize the functionality of this website. The American Provisional Tank Group had been in the Philippines only three weeks when the Japanese attacked the islands hours after the raid on Pearl Harbor. World history: from c -. Captured at Kut, Prisoner of the Turks: The. Loses a star for its format, the 'log entries' get a little dry but the pictures and information is excellent. New copy picked straight from printer's box. Add to Basket. Check XE. Following separation from the Navy, Caldwell returned to Texas to begin a career in the chemical industry. Anthony Barne started his diary in August as a young, recently married captain in His first book, JG Top Guns of the Luftwaffe, has been followed by four others on the Luftwaffe: all have won critical and popular acclaim for their accuracy, objectivity, and readability. W J Mott rated it it was amazing Dec 17, Available in the following formats: Hardback ePub Kindle. The previous volume in this series, The Luftwaffe over Germany: Defence of the Reich is an award-winning narrative history published by Greenhill Books. -

The Pillars of American Grand Strategy in World War II by Tami Davis Biddle

Leveraging Strength: The Pillars of American Grand Strategy in World War II by Tami Davis Biddle Tami Davis Biddle is the Hoyt S. Vandenberg Chair of Aerospace Studies at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, PA. She is the author of Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare: The Evolution of British and American Thinking about Strategic Bombing, 1914–1945, and is at work on a new book titled, Taking Command: The United States at War, 1944–1945. This article is based on a lecture she delivered in March 2010 in The Hertog Program on Grand Strategy, jointly sponsored by Temple University’s Center for Force and Diplomacy, and FPRI. Abstract: This article argues that U.S. leaders navigated their way through World War II challenges in several important ways. These included: sustaining a functional civil-military relationship; mobilizing inside a democratic, capitalist paradigm; leveraging the moral high ground ceded to them by their enemies; cultivating their ongoing relationship with the British, and embra- cing a kind of adaptability and resiliency that facilitated their ability to learn from mistakes and take advantage of their enemies’ mistakes. ooking back on their World War II experience from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, Americans are struck, first of all, by the speed L with which everything was accomplished: armies were raised, fleets of planes and ships were built, setbacks were overcome, and great victories were won—all in a mere 45 months. Between December 1941 and August 1945, Americans faced extraordinary challenges and accepted responsibilities they had previously eschewed. -

De Havilland Technical School, Salisbury Hall .46 W

Last updated 1 July 2021 ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| DeHAVILLAND DH.98 MOSQUITO ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| 98001 • Mk. I W4050 (prototype E-0234): built Salisbury Hall, ff Hatfield 25.11.40 De Havilland Technical School, Salisbury Hall .46 W. J. S. Baird, Hatfield .46/59 (stored Hatfield, later Panshanger, Hatfield, Chester, Hatfield: moved to Salisbury Hall 9.58) Mosquito Aircraft Museum/ De Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre, Salisbury Hall, London Colney 5.59/20 (complete static rest. 01/03, remained on display, one Merlin rest. to running condition) _______________________________________________________________________________________ - PR Mk. IV DK310 forced landing due engine trouble, Berne-Belpmoos, Switzerland: interned 24.8.43 (to Swiss Army as E-42) HB-IMO Swissair AG: pilot training 1.1.45 (to Swiss AF as B-4) 7.8.45/53 wfu 9.4.53, scrapped 4.12.53 _______________________________________________________________________________________ - PR Mk. IV DZ411 G-AGFV British Overseas Airways Corp, Leuchars 12.42/45 forced landing due Fw190 attack, Stockholm 23.4.43 dam. take-off, Stockholm-Bromma 4.7.44 (returned to RAF as DZ411) 6.1.45 _______________________________________________________________________________________ -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

The Story of Sid Bregman 80 Glorious Years

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 CANADIAN WARPLANE HERITAGE MUSEUM 80 GLORIOUS YEARS Canadian Warplane Heritage’s DC-3 THE STORY OF SID BREGMAN And Spitfire MJ627 President & Chief Executive Officer David G. Rohrer Vice President – External Client Services Manager Controller Operations Cathy Dowd Brenda Shelley Sandra Price Curator Education Services Vice President – Finance Erin Napier Manager Ernie Doyle Howard McLean Flight Coordinator Chief Engineer Laura Hassard-Moran Donor Services Jim Van Dyk Manager Retail Manager Sally Melnyk Marketing Manager Shawn Perras Al Mickeloff Building Maintenance Volunteer Services Manager Food & Beverage Manager Administrator Jason Pascoe Anas Hasan Toni McFarlane Board of Directors Christopher Freeman, Chair David Ippolito Robert Fenn Sandy Thomson, Ex Officio John O’Dwyer Patrick Farrell Bruce MacRitchie, Ex Officio David G. Rohrer Art McCabe Nestor Yakimik, Ex Officio Barbara Maisonneuve David Williams Stay Connected Subscribe to our eFlyer Canadian Warplane warplane.com/mailing-list-signup.aspx Heritage Museum 9280 Airport Road Read Flightlines online warplane.com/about/flightlines.aspx Mount Hope, Ontario L0R 1W0 Like us on Facebook facebook.com/Canadian Phone 905-679-4183 WarplaneHeritageMuseum Toll free 1-877-347-3359 (FIREFLY) Fax 905-679-4186 Follow us on Twitter Email [email protected] @CWHM Web warplane.com Watch videos on YouTube youtube.com/CWHMuseum JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 Shop our Gift Shop warplane.com/gift-shop.aspx CANADIAN WARPLANE HERITAGE MUSEUM Follow Us on Instagram instagram.com/ canadianwarplaneheritagemuseum Volunteer Editor: Bill Cumming Flightlines is the official publication of the Canadian 80 GLORIOUS YEARS Canadian Warplane Heritage’s DC-3 Warplane Heritage Museum. It is a benefit of membership THE STORY OF SID BREGMAN And Spitfire MJ627 and is published six times per year (Jan/Feb, Mar/Apr, May/June, July/Aug, Sept/Oct, Nov/Dec). -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

LET's GO FLYING Book, at the Perfect Landing Restaurant, Centennial Airport Near Denver, Colorado

Cover:Layout 1 12/1/09 11:02 AM Page 1 LET’S GO LET’S FLYING G O FLYING Educational Programs Directorate & Drug Demand Reduction Program Civil Air Patrol National Headquarters 105 South Hansell Street Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala. 36112 Let's Go Fly Chapter 1:Layout 1 12/15/09 7:33 AM Page i CIVIL AIR PATROL DIRECTOR, EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS DIRECTORATE Mr. James L. Mallett CHIEF, DRUG DEMAND REDUCTION PROGRAM Mr. Michael Simpkins CHIEF, AEROSPACE EDUCATION Dr. Jeff Montgomery AUTHOR & PROJECT DIRECTOR Dr. Ben Millspaugh EDITORIAL TEAM Ms. Gretchen Clayson; Ms. Susan Mallett; Lt. Col. Bruce Hulley, CAP; Ms. Crystal Bloemen; Lt. Col. Barbara Gentry, CAP; Major Kaye Ebelt, CAP; Capt. Russell Grell, CAP; and Mr. Dekker Zimmerman AVIATION CAREER SUPPORT TEAM Maj. Gen. Tandy Bozeman, USAF Ret.; Lt. Col. Ron Gendron, USAF; Lt. Col. Patrick Hanlon, USAF; Capt. Billy Mitchell, Capt. Randy Trujillo; and Capt. Rick Vigil LAYOUT & DESIGN Ms. Barb Pribulick PHOTOGRAPHY Mr. Adam Wright; Mr. Alex McMahon and Mr. Frank E. Mills PRINTING Wells Printing Montgomery, AL 2nd Edition Let's Go Fly Chapter 1:Layout 1 12/15/09 7:33 AM Page ii Contents Part One — Introduction to the world of aviation — your first flight on a commercial airliner . 1 Part Two — So you want to learn to fly — this is your introduction into actual flight training . 23 Part Three — Special programs for your aviation interest . 67 Part Four Fun things you can do with an interest in aviation . 91 Part Five Getting your “ticket” & passing the medical . 119 Part Six Interviews with aviation professionals . -

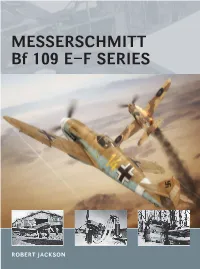

Messerschmitt Bf 109 E–F Series

MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON 19/06/2015 12:23 Key MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109E-3 1. Three-blade VDM variable pitch propeller G 2. Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine, 12-cylinder inverted-Vee, 1,150hp 3. Exhaust 4. Engine mounting frame 5. Outwards-retracting main undercarriage ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND ILLUSTRATOR 6. Two 20mm cannon, one in each wing 7. Automatic leading edge slats ROBERT JACKSON is a full-time writer and lecturer, mainly on 8. Wing structure: All metal, single main spar, stressed skin covering aerospace and defense issues, and was the defense correspondent 9. Split flaps for North of England Newspapers. He is the author of more than 10. All-metal strut-braced tail unit 60 books on aviation and military subjects, including operational 11. All-metal monocoque fuselage histories on famous aircraft such as the Mustang, Spitfire and 12. Radio mast Canberra. A former pilot and navigation instructor, he was a 13. 8mm pilot armour plating squadron leader in the RAF Volunteer Reserve. 14. Cockpit canopy hinged to open to starboard 11 15. Staggered pair of 7.92mm MG17 machine guns firing through 12 propeller ADAM TOOBY is an internationally renowned digital aviation artist and illustrator. His work can be found in publications worldwide and as box art for model aircraft kits. He also runs a successful 14 13 illustration studio and aviation prints business 15 10 1 9 8 4 2 3 6 7 5 AVG_23 Inner.v2.indd 1 22/06/2015 09:47 AIR VANGUARD 23 MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON AVG_23_Messerschmitt_Bf_109.layout.v11.indd 1 23/06/2015 09:54 This electronic edition published 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Osprey Publishing, PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA E-mail: [email protected] Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc © 2015 Osprey Publishing Ltd. -

NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL (NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946 Page numbers in braces refer to IMT, judgment of 1 October 1946, in The Trial of German Major War Criminals. Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg, Germany , Part 22 (22nd August ,1946 to 1st October, 1946) 1 {iii} THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL IN SESSOIN AT NUREMBERG, GERMANY Before: THE RT. HON. SIR GEOFFREY LAWRENCE (member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) President THE HON. SIR WILLIAM NORMAN BIRKETT (alternate member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) MR. FRANCIS BIDDLE (member for the United States of America) JUDGE JOHN J. PARKER (alternate member for the United States of America) M. LE PROFESSEUR DONNEDIEU DE VABRES (member for the French Republic) M. LE CONSEILER FLACO (alternate member for the French Republic) MAJOR-GENERAL I. T. NIKITCHENKO (member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) LT.-COLONEL A. F. VOLCHKOV (alternate member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) {iv} THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS Against: Hermann Wilhelm Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Robert Ley, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Julius Streicher, Walter Funk, Hjalmar Schacht, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, Martin -

The German Rocket Jet and the Nuclear Programs of World War II Max Lutze Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 The German Rocket Jet and the Nuclear Programs of World War II Max Lutze Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the European History Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Lutze, Max, "The German Rocket Jet and the Nuclear Programs of World War II" (2016). Honors Theses. 179. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/179 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The German Rocket, Jet, and Nuclear Programs of World War II By Max Lutze * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2016 2 Abstract German military technology in World War II was among the best of the major warring powers and in many cases it was the groundwork for postwar innovations that permanently changed global warfare. Three of the most important projects undertaken, which were not only German initiatives and therefore perhaps among the most valuable programs for both the major Axis and Allied nations, include the rocket, jet, and nuclear programs. In Germany, each of these technologies was given different levels of attention and met with varying degrees of success in their development and application. -

Hitler's Grotesque Economics

Hitler’s grotesque economics Tooze describes Speer as a power Sinclair Davidson reviews hungry man who inflated his own abili- The Wages of Destruction: ties and expanded his bureaucratic em- pire. Ultimately Speer is portrayed as a The Making and Breaking self-serving bureaucrat and a spin-doctor. of the Nazi Economy It is difficult to know what to make of by Adam Tooze Tooze’s portrayal of Speer. Being a spin- (Allen Lane, 2007, 799 pages) doctor is not a crime against humanity. Speer may have been morally complicit in many of the crimes of Nazi Germany, n the acclaimed television series but Tooze’s new evidence is not enough Band of Brothers the Webster char- to doubt the judgement at Nuremberg— acter abuses a column of German I which chose to merely imprison, rather prisoners of war, ‘Say hello to Ford, and than execute, Speer. General fuckin’ Motors. You stupid fas- murder millions and millions of people. Ultimately Germany lost the war be- cist pigs. Look at you. You have horses. The Holocaust was not simply a case of cause they could not match the resources What were you thinking?’ In The Wages murdering a hated minority; it was the of the Americans, British, and Soviet of Destruction: The Making and Breaking starting point of a planned mass murder economies. Had the Allies done more to of the Nazi Economy, a recent and contro- on a far greater scale. destroy the German economy, the war versial book Adam Tooze, senior lecturer The war had caused substantial eco- could have ended earlier—more bomb- in economic history at Cambridge, sets nomic problems in Europe.