Here in Its Entirety) Seems Able to Embody My Particular Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearing Nostalgia in the Twilight Zone

JPTV 6 (1) pp. 59–80 Intellect Limited 2018 Journal of Popular Television Volume 6 Number 1 © 2018 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jptv.6.1.59_1 Reba A. Wissner Montclair State University No time like the past: Hearing nostalgia in The Twilight Zone Abstract Keywords One of Rod Serling’s favourite topics of exploration in The Twilight Zone (1959–64) Twilight Zone is nostalgia, which pervaded many of the episodes of the series. Although Serling Rod Serling himself often looked back upon the past wishing to regain it, he did, however, under- nostalgia stand that we often see things looking back that were not there and that the past is CBS often idealized. Like Serling, many ageing characters in The Twilight Zone often sentimentality look back or travel to the past to reclaim what they had lost. While this is a perva- stock music sive theme in the plots, in these episodes the music which accompanies the scores depict the reality of the past, showing that it is not as wonderful as the charac- ter imagined. Often, music from these various situations is reused within the same context, allowing for a stock music collection of music of nostalgia from the series. This article discusses the music of nostalgia in The Twilight Zone and the ways in which the music depicts the reality of the harshness of the past. By feeding into their own longing for the reclamation of the past, the writers and composers of these episodes remind us that what we remember is not always what was there. -

Mmes. Carter and Mondale Attend SI Events V Mrs

o THE SMITHSONIAN TORCH No. 78-8 Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. August 1978 Mmes. Carter and Mondale Attend SI Events v Mrs. Carter Donates Gown; Hall Space To Be Expanded Tourists starting the ir museum . visits earl y on Jul y 20 were rewarded when RosaIynn Carter came to the Smithsonian to donate her Inaugural Ball gown in a public ceremony at the Mu seum of History and Technology. In accepting the blue chiffon gown de signed by Mary Matise , Secretary Ripley said, " This is a very special dress Mrs . Carter gives us today. It is one for which she has a very sentimental attachment be cause she first wore it in 1971 at the inau gural ball in Georgia when her husband be came Governor of Georgia. To the delight of the nation , she chose to wear that same gown again for the balls in Washington when her husband was inaugurated as President of the United States. The dual role of the gown makes it one of the most interesting to become part of the collection . " Ripley al so announced plans for the ex pansion of the First Ladies Hall , one of the Smithsonian 's most popular exhibits. He said that the crowded conditions which now exist in the Hall would be alleviated with the addition of a new exhibit setting based After presenting her Inaugural Ball gown to the Smithsonian, Mrs. Carter posed with Secretary Ripley and political history on the White House Red Room as it looked Curator Margaret Klapthor. See related photo, Page 5. durin g the admi ni stration of John F. -

HIRSHHORN MUSEUM and SCULPTURE GARDEN LIBRARY VIDEO COLLECTION Recordings May Not Be Usable in Current Format

HIRSHHORN MUSEUM AND SCULPTURE GARDEN LIBRARY VIDEO COLLECTION Recordings may not be usable in current format. Check with Library staff. Video materials are not circulated. (updated August 26, 2008) VHS TAPES 1. 41-10 Mr. & Mrs. Chagall, daughter, son-in-law 2. 74-60 HMSG Opening Ceremonies 3. 74-90 Visit of architect Gordon Bunshaft 4. 74-210 Hirshhorn Museum dedication ceremony 5. 75-00 Hirshhorn: Man and Museum-Camera 3 6. 76-20 A life of its own, v-1 7. 79-50 John Baldessari 8. 87-20 Mark Di Suvero: Storm King 9. 88-20 “Cornered” video Installation (Adrian piper piece) 10. 89-20 Buster Simpson (HMSG) 11. 90-30 Scenes and Songs from Boyd Webb (video documentary) 12. 92-80 Robert Irwin- In response 13. 93-20 Paul Reed Catalog #9-1936-1992 (artists’ work) 14. 93-30 Collection that Became a Museum (Smithsonian Film Transfer) 15. 93-30 Collection that Became a Museum (copy) 16. 93-50 A life of its own 17. 93-50 A life of its own 1976 18. 96-20 Thomas Eakins and the Swimming Picture 19. 96-60 Beverly Semmes 20. 97-10 Judith Zilczer interview on De Kooning 21. 97-80 Jeff Wall segment 22. 97-100 Willem De Kooning 23. 98-10 George Segal (HMSG) 24. 98-20 George Segal-Dialogue (HMSG) 25. 00-30 The Ephemeral is Eternal (De Stijl play) 26. 00-40 Gary Hill- Dig 27. 00-60 Willem De Kooning 28. 00-100 The collection that became a Museum-Ron J. Cavalier (HMSG) 29. 1974 Visit of Architect Bunshaft (HMSG) 30. -

The Republican Journal Vol. 87, No. 12

Today’s Journal. of A flock of ents _-- UB1TUARY. large wild geese flew over Belfast W“8 News of Belfast last the Granges. .Obituary... much respected, and The bay Monday afternoon—another sign of PERSONAL” PERSONAL. had many frienda societies. .The News of Bel- It was with a shock and sense of loss that in Pittsfield and eurround- spring. The War News... the friends in .ng owns who extend crePersonal.. Belfast learned of the death in sympathy to those who THE MARCH WIND. Mr. J. W. Roberts writes from Mrs. E. 0. Clement of Wedding Bells, «e left Reading. Mrs. John O. Black is her mother Pittsfield is visiting flections.. March of to mourn their visiting in sln Boston, I8th, Miss Clara Prentiss loss, Mr. was The March wind is a saucy sprite, Mass: “Have returned relatives in Pacific Exposition. .One Bagle, just from Orlando and Union. Montville. '^r-.iiiiina Parsons. She had been ill some Bnd i8 He blows skirts awry Another. .A weeks, but survived by a widow, girls’ St. Augustine, Florida, where we met Suggests Mrs down the some Emerton Gross has returned from Sconce was to be Mr'eJn!'1",edNell,e W. And sends bats rolling street, Miss Bernice Holt returned from Camden, Letter. .Recent Deaths. supposed improving slowly, when Bagley. with whom he was Belfast people.*' Monday ^,r united in To cheer the passers-by. where he spent the week's school vacation with on March 10th a sudden marriage about Warren, where she spent the Easter recess. ... \ew York. .Shamrocks at change for the worse years dust thin,-five ago, He fills the air with blinding We have received an hie A. -

Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes.Xlsx

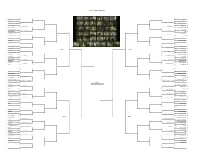

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last 57 56 Eye of the Beholder 1 Time Enough at Last Eye of the Beholder 32 The Fever 4 5 The Mighty Casey 32 16 A World of Difference 25 19 The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 I Shot an Arrow into the Air A Most Unusual Camera 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 35 41 A Most Unusual Camera 17 8 Third from the Sun 44 37 The Howling Man 8 Third from the Sun The Howling Man 25 A Passage for Trumpet 16 Nervous22 Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 34 45 The Invaders 9 Love Live Walter Jameson The Invaders 24 The Purple Testament 25 13 Dust 24 5 The Hitch-Hiker 52 41 The After Hours 5 The Hitch-Hiker The After Hours 28 The Four of Us Are Dying 8 19 Mr. Bevis 28 12 What You Need 40 31 A World of His Own 12 What You Need A World of His Own 21 Escape Clause 19 28 The Lateness of the Hour 21 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 37 48 The Silence 4 And When the Sky Was Opened The Silence 29 The Chaser 21 11 The Mind and the Matter 29 13 A Nice Place to Visit 35 35 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit The Night of the Meek 20 Perchance to Dream 24 24 The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Season 2 6 Walking Distance 37 43 Nick of Time 6 Walking Distance Nick of Time 27 Mr. -

George V. Barton Reminiscences, 1982-1983

Olga Hirshhorn Oral History Interviews, 1986-1988 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Olga Hirshhorn Oral History Interviews https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_217734 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Olga Hirshhorn Oral History Interviews Date: 1986-1988 Identifier: Record Unit 9566 Creator:: Hirshhorn, Olga, interviewee Extent: 18 audiotapes (Reference copies). Language: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, -

New to Hoopla

New to Hoopla - January 2014 A hundred yards over the rim Audiobook Rod Serling 00:37:00 2013 A most unusual camera Audiobook Rod Serling 00:38:00 2013 A murder in passing Audiobook Mark DeCastrique 08:35:00 2013 A sea of troubles Audiobook P. G. Wodehouse 00:30:00 2013 A short drink from a certain fountain Audiobook Rod Serling 00:39:00 2013 A small furry prayer Audiobook Steven Kotler 09:30:00 2010 A summer life Audiobook Gary Soto 03:51:00 2013 Accelerated Audiobook Bronwen Hruska 10:36:00 2013 American freak show Audiobook Willie Geist 05:00:00 2010 An amish miracle Audiobook Beth Wiseman 10:13:22 2013 An occurrence at owl creek bridge Audiobook Ambrose Bierce 00:28:00 2013 Andrew jackson's america: 1824-1850 Audiobook Christopher Collier 02:03:00 2013 Angel guided meditations for children Audiobook Michelle Roberton-Jones 00:39:00 2013 Animal healing workshop Audiobook Holly Davis 01:01:00 2013 Antidote man Audiobook Jamie Sutliff 08:23:00 2013 Ashes of midnight Audiobook Lara Adrian 10:00:00 2010 At the mountains of madness Audiobook H. P. Lovecraft 04:48:00 2013 Attica Audiobook Garry Kilworth 09:46:00 2013 Back there Audiobook Rod Serling 00:35:00 2013 Below Audiobook Ryan Lockwood 09:52:00 2013 Beyond lies the wub Audiobook Philip K. Dick 00:22:00 2013 Bittersweet love Audiobook Rochelle Alers 06:21:00 2013 Bottom line Audiobook Marc Davis 07:31:00 2013 Capacity for murder Audiobook Bernadette Pajer 07:52:00 2013 Cat in the dark Audiobook Shirley Rousseau Murphy 09:14:00 2013 Cat raise the dead Audiobook Shirley Rousseau Murphy -

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden LIST of FILMS / VIDEOS January 9, 2004

Hirshhorn Museum And Sculpture Garden LIST OF FILMS / VIDEOS January 9, 2004 1941 41-10 Mr. and Mrs. Chagall, daughter, son-in-law 1962 62-10 Guggenheim : Hirshhorn exhibition – no sound b&w one light work print positive (film) 62-20 Abram Lerner : sculpture at the Guggenheim “SS print” (film) 62-30 B&w negative picture Hirshhorn Exhibition (film – 5 reels) 1964 64-10 Interview – Abram Lerner and Joseph H. Hirshhorn (film?) 1974 74-60 HMSG Opening Ceremonies (video) 74-90 Visit of architect Gordon Bunshaft (2c.Beta, film) 74-100 Visit of Mr. Joseph H. Hirshhorn – 16mm work print (film) 74-110 Hirshhorn Remote Panorama (video – 2 reels) 74-210 Hirshhorn Museum Dedication ceremony (VHS) 1975 75-00 Hirshhorn: Man and Museum - Camera 3 (VHS) 75-10 Hirshhorn: Man and Museum - Camera 3b (video) 1976 76-10 Here at Smithsonian: California Artist - Robert Arneson (video) 76-20 A life of its own, v-1 (missing) 76-30 A life of its own, v-2 (missing) 1977 77-20 Checkerboard Foundation presents Brice Marden (missing) 1978 78-190 “Golden Door” 16mm original John Nugent (film) 1979 79-50 John Baldessari (VHS) 1980 1 80-20 Josef Albers, Commemorative Stamp Ceremony (video – 2 reels) 80-50 The Avant-Garde in Russia (video) 80-70 Victory over the Sun (play for RAG show) (video) 80-80 Victory over the Sun- Avant-Garde in Russia (play for RAG show) (video) 1981 81-10 5-minute Masters - Roger Brown (video) 1982 82-40 De Stijl - Vision of Utopia (video) 82-45 The Ephemeral is Eternal (play with sets by Piet Mondrian) (video) 82-48 Ephemeral is Eternal (unedited -

Transcript of the Journal of the Rev. Ashbel Green

7 1/ JOURNAL OP THE REVEREND ASHBEL GREi'N SIHONTON. On looking over the journal which I kept during my trip South, and whicl^I thought had "been destroyed or lost, I havo come to the conclusion to make use of it in filling up the hi- atus between the time of leaving home and the commencement of{jn my Hebdomad. It gives an account of some experiences which should not be lost and though no manner of care was given to the writing of it, yet it is interesting occasionally to look over it* It is very common to hear College Students speak of ths dull- ness of student like and to long for the "active scenqes of life", " to pass on to the stage of action" etc. I had often too looked forward to this future with considerable interest, even whilst being quietly amused at those pet school boy expressions which seemed to me only less dim, shadowy and undefined than Jfwere the ideas to which they were intended to give expression. It may therefore be interesting, by way of contrast, to record this account of m^ entrance upon the active duties of life and mark how nearly the reality agrees with the ideal of a school- boy's imagination. But to the Journal. 1852 Norfolk, Nov. 5th, 1852. Nov. 5. Our ride to Baltimore was very tedious, it being nearly twelve J on our arrival. Though I had never travelled over the road, yet the scenery after leaving the Susquehanna is so little inter- esting, that I soon turned from it, to indulge such feelings as natura ly forced themselves upon one leaving home, ofr the first time to sojourn for so long a time, a stanger in a strange land. -

Start Typing Here

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE HISTORIC PRESERVATION REVIEW BOARD APPLICATION FOR HISTORIC LANDMARK OR HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION New Designation _____ for: Historic Landmark ____ Historic District ____ Amendment of a previous designation _____ Please summarize any amendment(s) _______________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ Property name ____________________________________________________________________ If any part of the interior is being nominated, it must be specifically identified and described in the narrative statements. Address _________________________________________________________________________ Square and lot number(s) ___________________________________________________________ Affected Advisory Neighborhood Commission __________________________________________ Date of construction _______________ Date of major alteration(s) __________________________ Architect(s) ________________________ Architectural style(s) ____________________________ Original use ____________________________ Present use ________________________________ Property owner ____________________________________________________________________ Legal address of property owner ______________________________________________________ NAME OF APPLICANT(S) _________________________________________________________ If the applicant is an organization, it must submit evidence that among its purposes is the promotion of historic preservation in the -

Rod Serling Papers, 1945-1969

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5489n8zx No online items Finding Aid for the Rod Serling papers, 1945-1969 Finding aid prepared by Processed by Simone Fujita in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Kelley Wolfe Bachli, 2010. Prior processing by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Rod Serling 1035 1 papers, 1945-1969 Descriptive Summary Title: Rod Serling papers Date (inclusive): 1945-1969 Collection number: 1035 Creator: Serling, Rod, 1924- Extent: 23 boxes (11.5 linear ft.) Abstract: Rodman Edward Serling (1924-1975) wrote teleplays, screenplays, and many of the scripts for The Twilight Zone (1959-65). He also won 6 Emmy awards. The collection consists of scripts for films and television, including scripts for Serling's television program, The Twilight Zone. Also includes correspondence and business records primarily from 1966-1968. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. -

Joseph H. Hirshhorn Papers, 1921-1981, 1996

Joseph H. Hirshhorn Papers, 1921-1981, 1996 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Joseph H. Hirshhorn Papers https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_389075 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Joseph H. Hirshhorn Papers Identifier: Accession 17-126 Date: 1921-1981, 1996 Extent: 1.88 cu. ft. (1 record storage box) (1 16x20 box) (0.19 non- standard size boxes) Creator:: Hirshhorn, Joseph H. Language: Language of Materials: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 17-126, Joseph H. Hirshhorn Papers Access Restriction Box 1 contains restricted materials; see finding aid. Descriptive Entry This accession consists of papers of Joseph H. Hirshhorn. Joseph Hirshhorn was born