The Lark Ascending As an Elegy for Environmental Disruption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaughan Williams

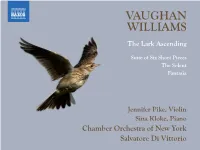

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS The Lark Ascending Suite of Six Short Pieces The Solent Fantasia Jennifer Pike, Violin Sina Kloke, Piano Chamber Orchestra of New York Salvatore Di Vittorio Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): The Lark Ascending a flinty, tenebrous theme for the soloist is succeeded by an He rises and begins to round, The Solent · Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra · Suite of Six Short Pieces orchestral statement of a chorale-like melody. The rest of He drops the silver chain of sound, the work offers variants upon these initial ideas, which are Of many links without a break, rigorously developed. Various contrasting sections, In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake. Vaughan Williams’ earliest compositions, which date from The opening phrase of The Solent held a deep significance including a scherzo-like passage, are heralded by rhetorical 1895, when he left the Royal College of Music, to 1908, for the composer, who returned to it several times throughout statements from the soloist before the coda recalls the For singing till his heaven fills, the year he went to Paris to study with Ravel, reveal a his long creative life. Near the start of A Sea Symphony chorale-like theme in a virtuosic manner. ’Tis love of earth that he instils, young creative artist attempting to establish his own (begun in the same year The Solent was written), it appears Vaughan Williams’ mastery of the piano is evident in And ever winging up and up, personal musical language. He withdrew or destroyed imposingly to the line ‘And on its limitless, heaving breast, the this Fantasia and in the concerto he wrote for the Our valley is his golden cup many works from that period, with the notable exception ships’. -

Cheryl Ann Durgan Eduard J. Hamilton

In memory of Cheryl Ann Durgan Cheryl Ann Durgan, 59, of Gardiner Road died Cheryl Ann was always positive. She loved her birds, Wednesday, May 2, 2012, at her residence. dogs and cats. She would go to the animal shelter fre- She was born in Troy, N.Y., on Jan. 14, 1953, a daughter quently and come home with a new pet. of William H. and Rose P. (Snyder) Hoffman. She was president of Maine State Caged Bird Society She graduated from Averill Park High School in New and president of the Capital Area Wheels R.V. Club/Good York in 1971. She attended many colleges and was recently Sam. attending University of Maine. She is survived by her husband, Richard A. Durgan, of She was employed by the City of Bath as head of general Dresden; two sons, Bryan Lewis, and his wife, Alyason, of assistance for 18 years. On Oct. 1, 2001, she was employed Maryland, and Brett Lewis and his wife, Melissa, of Mary- as activities director for Augusta Rehabilitation, Country land; one sister, Darlene R. Schnoop, and her husband, Manor in Coopers Mills, Field Crest Nursing Home and Mike, of Augusta; five grandchildren; many great-grand- as a coordinator for Catholic Charities in Augusta. children; and numerous nieces and nephews. Eduard J. Hamilton By Josef Lindholm III, Curator of Birds, Tulsa Zoo I saw Elvis in Tijuana. It was Elvis in his decline, heavy- set, in that iconic white high-collared suit glittering with rhinestones. His hair was a brilliant orange yellow. But all that garishness did not compare to the burden he bore: Five boxy wooden cages, each with at least a dozen male Painted Buntings, strung down his back. -

Tournament 11 Round #9

Tournament 11 Round 9 Tossups 1. This man described the homosexuality of Kochan in his work Confessions of a Mask. He wrote another work in which Isao (EYE-sow), Ying Chan, and Toru are all successive incarnations of Kiyaoki, who appears in Spring Snow. That work by this author centers on the lawyer Shigekuni Honda. This author ended a novel with Mizoguchi's arson of the titular (*) Temple of the Golden Pavilion. All of those works were completed prior to this author's televised suicide by seppuku (SEH-puh-koo). For 10 points, name this Japanese author who wrote the Sea of Fertility tetralogy. ANSWER: Yukio Mishima [or Mishima Yukio; do not accept or prompt on "Yukio" by itself; or Kimitake Hiraoka; or Hiraoka Kimitake; do not accept or prompt on "Kimitake" by itself] 020-09-10-09102 2. This man's first symphony sets poems from Whitman's Leaves of Grass and contains the movements "The Explorers" and "On the Beach at Night Alone". He wrote a piece for violin and orchestra based on a George Meredith poem that depicts a (*) bird rising up to the heavens. Another of this man's works was inspired by the music of the composer of the motet Spem in alium. For 10 points, identify this British composer of A Sea Symphony and The Lark Ascending who wrote fantasias on "Greensleeves" and on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. ANSWER: Ralph Vaughan Williams 029-09-10-09103 3. This politician decried the forced removal of Ali Maher as an attack on his nation's sovereignty. -

Copyright 2014 Renée Chérie Clark

Copyright 2014 Renée Chérie Clark ASPECTS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE ART SONGS OF RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS BEFORE THE GREAT WAR BY RENÉE CHÉRIE CLARK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christina Bashford, Chair Associate Professor Gayle Sherwood Magee Professor Emeritus Herbert Kellman Professor Emeritus Chester L. Alwes ABSTRACT This dissertation explores how the art songs of English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) composed before the Great War expressed the composer’s vision of “Englishness” or “English national identity”. These terms can be defined as the popular national consciousness of the English people. It is something that demands continual reassessment because it is constantly changing. Thus, this study takes into account two key areas of investigation. The first comprises the poets and texts set by the composer during the time in question. The second consists of an exploration of the cultural history of British and specifically English ideas surrounding pastoralism, ruralism, the trope of wandering in the countryside, and the rural landscape as an escape from the city. This dissertation unfolds as follows. The Introduction surveys the literature on Vaughan Williams and his songs in particular on the one hand, and on the other it surveys a necessarily selective portion of the vast literature of English national identity. The introduction also explains the methodology applied in the following chapters in analyzing the music as readings of texts. The remaining chapters progress in the chronological order of Vaughan Williams’s career as a composer. -

Mikrokosmos Labelography ...20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 594. - 2 - January 2015 ....MIKROKOSMOS LABELOGRAPHY 1 Mikrokosmos Labelography Vol.1+2: 240 color labels with specially designed MIKROKOSMO VOL. 12 A++ 78 plastic folders and binder (Decca, EMI, Melodiya, Mercury, RCA, etc) 2 Mikrokosmos Labelography Vol.3-4: Additional 192 color labels with specially MIKROKOSMO VOL. 34 A++ 58 designed plastic folders (Decca, EMI, Melodiya, Mercury, RCA) 3 Mikrokosmos Labelography Vol.5-6: Additional 192 color labels with specially MIKROKOSMO VOL. 56 A++ 68 designed plastic folders (Ducretet-Thomson, Decca, EMI, etc) (postage at www.mikrokosmos.com/labelography.asp) ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 4 Absil, Jean: 3 T.Klingson Poems, Batterie aftre Cocteau, Toccata (pno), Phantasmes DECCA 143235 A 40 (pno, perc, sax) - Y.Martens, A.Dumortier, Coutelier, Daneels 10" 5 Adams, John: Nixon in China excs - Sylvan, Maddalena, Opatz, cond.de Waart NONESUCH 979193 A 10 1987 S 6 Ager, Klaus: I Remember a Bird (cl, trombone, gtr, pno, perc, tape), ...Sondern FSM 53544 A 50 (tape), Metaboles (cl, vln, vcl, pno) - Neue Music Ens S 7 Arma, Paul: Div de Concert No.1/ Damase: Serenade/ Ibert: Fl Con - Rampal, ERATO STU 71022 A 10 FB2 cond.Girard, Froment (gatefold) 1965-77 S 8 Arutunian: Tr Con/V.Kriukov: Concert-Poem (tr, orch)/M.Vainberg: Tr Con - DGG 2530618 A 12 Dokshitser, cond.Zuraitis (1971) S 9 Babadzhanian: Pno Trio/Roslavets: Pno Trio/Shostakovich: Pno Trio Op.8 - SIGNUM SIG 1300 A 15 Seraphin Trio (1986) S 10 Barazzetti, Luigi: Toccata (vla, pno), Ad Matris Memoriam (vln, pno), Momento NAZIONALMU -

Birds of Britain 2019

Field Guides Tour Report Birds of Britain 2019 May 11, 2019 to May 20, 2019 Megan Edwards Crewe & Willy Perez For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Endearing European Robins were a regular sighting throughout the tour. Photo by participant Jeanette Shores. After a long hiatus, we reintroduced the Birds of Britain tour to our schedule this year, with tweaks to the old itinerary to include some new locations and a few cultural highlights. England pulled out all the stops for our visit -- giving us gorgeous azure skies and balmy days for much of our stay, and offering up a raft of surprises among the more expected breeding species. Scotland proved a bit more chilly and temperamental, dumping rain on us on several mornings, but tempering that with some spectacular views and a sunny finale as well as some distinctly "highland" sightings. We started with a 10-day exploration of East Anglia, venturing from the coastal reserves of RSPB Minsmere and RSPB Titchwell, and the remnant heathlands of Dunwich and Westleton, to the vast, flat Norfolk broads, the farm fields along Chalkpit Lane and the grand estates of Felbrigg, Blickling and Lynford (the latter's arboretum now part of Thetford Forest). We reveled in repeated encounters with many of "the regulars" -- breeding species such as European Robin, Song Thrush, Dunnock, Eurasian Blackbird, Chiffchaff, Sedge Warbler, House Martin, and multiple species of tits. Remember the line of eight just-fledged Long-tailed Tits huddled together on a branch, waiting for their parents to return with tidbits? We also had close encounters with some less common breeders. -

PROGRAM NOTES Ralph Vaughan Williams the Lark Ascending

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Ralph Vaughan Williams Born October 12, 1872, Gloucestershire, England. Died August 26, 1958, London, England. The Lark Ascending, Romance for Violin and Orchestra Vaughan Williams composed this work for violin and piano in 1914. He thoroughly revised the score in 1919–20. The first performance, in a version with piano accompaniment, was given on December 15, 1920, and the premiere of the version for violin and orchestra was given on June 14, 1921, in London. The orchestra consists of two flutes, oboe, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, triangle, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirteen minutes. These are the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first performances of Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending. From the beginning of his career, in the first years of the twentieth century, Ralph Vaughan Williams was seen as a composer rooted in the past. His first significant large-scale work, the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis composed in 1910, is indebted to the music of his sixteenth-century predecessor and to the great English tradition. His entire upbringing was steeped in tradition—he was related both to the pottery Wedgwoods and Charles Darwin. (“The Bible says that God made the world in six days,” his mother told him. “Great Uncle Charles thinks it took longer: but we need not worry about it, for it is equally wonderful either way.”) He became a serious student of English folk song and edited the English Hymnal. Even the experience of studying with Ravel in 1908, which clearly enhanced his understanding of color and sonority, only served to sharpen his own individual style and to ground him more firmly in the sensibilities of his musical heritage. -

Crematorium Groningen

3 2 Pac mamma 4:39 4 3 Baritons Chanson du Toreador 4:21 5 3 baritons let my try again 3:24 6 3 baritons Perhaps love 3:05 7 3 Tenoren Santa Lucia 3:10 8 3 Tenoren Valencia 3:32 9 3 voices Goodnight irene 2:41 10 3 voices Jealous heart 1:57 11 3 voices My hapiness 2:11 15 Aafje Heynis Umbra mai fu 4:29 16 Aafje Heynis Ave Maria (Schubert) 4:15 18 Aafje Heynis Bereite dich zion 5:31 19 Aafje Heynis Bist du bei mir 3:16 20 Aafje Heynis Dank sei dir, Herr 4:18 21 Aafje Heynis Ombra 4:24 22 Aafje Heynis Panis Angelicus 4:00 23 Aafje Heynis La derniere feuille 1:45 24 Aafje Heynis Neem heer mijn beide handen 3:19 25 Aafje Heynis Ave Maria (live) 3:20 26 Aafje Heynis Ave maria 3:25 27 Aafje Heynis Schlafe mein liebster 10:08 6336 Aafje Heynis Op bergen en in dalen 3:15 7626 Aafje Heynis Mein jesu was fur Seelenweh 3:33 9765 Aafje Heynis Ave Maria 4:20 28 Abba Angel eyes 4:22 29 Abba Arrival 3:00 30 Abba As good as new 3:25 31 Abba Chiquitita 5:26 32 Abba Dancing Queen 3:48 33 Abba Does your mother know 3:15 34 Abba eagle 4:23 35 Abba I have a dream 4:37 36 Abba If it wasn't for the nights 5:11 37 Abba Kisses of fire 3:17 38 Abba Lovers 3:30 39 Abba Slippin trough my fingers 3:55 40 Abba The king has lost his crown 3:34 41 Abba The winner takes it all 4:56 42 Abba Voulez vous 5:08 43 Abba Thank you for the music 3:51 44 Abba Knowing you 4:03 45 Abba Fernando 4:12 46 Abba One of us 3:58 47 Abba Waterloo 2:46 48 Abba Eagle 5:46 7453 Abba The way old freinds do 2:48 8857 Abba SOS 3:22 49 Abba Pater Dove cé amore, cé dio 4:03 50 Abdykoor van St. -

Single-Page Format

EDWARD ELGAR : COLLECTED CORRESPONDENCE SERIES I VOLUME 2 AN ELGARIAN WHO'S WHO COMPILED BY MARTIN BIRD § § § Supplement 1 APRIL 2015 ELGARWORKS 2015 INTRODUCTION This is the first supplement to An Elgarian Who’s Who, published in 2014 by Elgar Works in the Edward Elgar: Collected Correspondence series. It comprises the following: & Correction of errors & Additional information unavailable at the time of publication & Additional entries where previously unknown Elgar correspondents have come to light. & Additional cross referencing & Family trees In the alphabetical entries which follow on pages 1–29, amendments and additions to the original text appear in red. Family trees have been compiled for the families of Alice’s innumerable cousins and aunts – the Dighton, Probyn, Raikes, Roberts and Thompson families. An editorial decision was made to exclude these from the original publication owing to their complexity, even in an abbreviated form. However, it is conceded that they are necessary as an aid to understanding the tangled relationships of Alice’s family, and so are included here. Names appearing in the trees in bold type are those members of the families mentioned in the Who’s Who, while spouses appear in italics. A tree is also included for the family of Roynon Jones. He, through his children and grandchildren, provided many spouses for the above-mentioned families. The family trees had been grouped together on pages that can be downloaded and printed separately on A3 or A4 paper. A-Z ABERDARE, LORD 1851–1929 Henry Campbell Bruce, 2nd Aberdare, was the eldest son of Henry Bruce, 1st Baron Aberdare, who had served as Home Secretary. -

Harmony, Tonality and Structure in Vaughan Williams's Music

Harmony, Tonality and Structure in Vaughan Williams's Music Volume 1 David Manning A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor of the University of Wales, Cardiff December 2003 Summary Many elements of and reflections on tonality are to be found in Vaughan Williams’s music: tonal centres are established and sustained, consonant triads are pervasive, and sonata form (a structure associated with tonality) is influential in the symphonies. But elements of the tonal system are also challenged: the diatonic scale is modified by modal alterations which affect the hierarchical relation of scale degrees, often consonant triads are not arranged according to the familiar patterns of functional harmony, and the closure of sonata form is compromised by the evasive epilogue ending of many movements and rotational structures. This music is not tonal or atonal, nor does it stand on any historical path between these two thoroughly theorised principles of pitch organisation. With no obvious single theoretical model at hand through which to explore Vaughan Williams’s music, this analysis engages with Schenkerian principles, Neo-Riemannian theory, and the idea of sonata deformation, interpreting selected extracts from various works in detail. Elements of coherence and local unities are proposed, yet disruptions, ambiguities, subversions, and distancing frames all feature at different stages. These are a challenge to the specific principle of organisation in question; sometimes they also raise concerns for the engagement of theory with this repertoire in general. At such points, meta-theoretical issues arise, while the overall focus remains on the analytical understanding of Vaughan Williams’s music. -

Vaughan Williams – the Lark Ascending

SECONDARY 10 PIECES PLUS! THE LARK ASCENDING by VAUGHAN WILLIAMS TEACHER PAGES THE LARK ASCENDING BY RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3l2p7df6Yhg8dRp20Hp85VG/ten-pieces-secondary CONTEXT The Lark Ascending – A Romance for Violin and Orchestra - was originally composed in 1914 for violin and piano and then orchestrated in 1921. It was inspired by an eponymous poem by George Meredith (1881) and evokes the vision of a lark floating freely in the sky on a peaceful summer’s day. These lines are inscribed in the score: He rises and begins to round, He drops the silver chain of sound Of many links without a break, In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake... For singing till his heaven fills, ’Tis love of earth that he instils, And ever winging up and up, Our valley is his golden cup, And he the wine which overflows To lift us with him as he goes... Till lost on his aërial rings In light, and then the fancy sings. The music is gentle and lyrical, reflecting an idyllic and calm scene in the English countryside in the period just before war broke out in Europe. The ‘sweet’ and reassuring mood is typical of much of Vaughan William’s ‘pastoral’ style which grew out of his interest in traditional music and reflected his national roots: this resonated with a movement pioneered by Cecil Sharp, who collected folk songs and established an archive of indigenous English music. The scales and modes present in folk songs shaped Vaughan Williams’ melodies and harmonies, giving his music the characteristic sound which pervades The Lark Ascending. -

Releases in Europe, May 2004

SUPER AUDIO CD RELEASES IN EUROPE, MAY 2004 Artist Title Label Catalogue Stereo Surround CD Audio number 1 3 Doors Down Away from the sun Universal Music 0 0440 038 080-2 7 SACD Stereo SACD Surround CD Audio 2 Salvatore Accardo, Laura Manzini The Violins of Cremona, Omaggio a Kreisler fonè SACD FONE 030 SACD Stereo - CD Audio 3 Acoustic Triangle Catalyst Audio-B ABCD 5015 SACD Stereo SACD Surround CD Audio 4 Acoustic Triangle Interactions Audio-B SABCD 5012 SACD Stereo SACD Surround CD Audio 5 Ryan Adams Gold Universal Music/ Lost 0 0088 170 336-2 4 SACD Stereo SACD Surround - Highway 6 Cannonball Adderley Salle Pleyel 1960 & Olympia 1961 Delta Music 52 016 SACD Stereo SACD Surround CD Audio 7 Cannonball Adderley With Bill Know What I Mean? Analogue Productions APJ 9433 SACD Stereo - CD Audio Evans 8 Adiemus Songs Of Sanctuary EMI/ Virgin Records 7243 8112692 9 SACD Stereo - CD Audio 9 Aerosmith Oh Yeah! Ultimate Aerosmith Hits (2 discs) Sony Music/ Columbia 508467 7 SACD Stereo - - 10 Aerosmith Toys in the Attic SonyMusic/ Columbia CS57362 SACD Stereo SACD Surround - 11 Aerosmith Just Push Play Sony Music/ Columbia CS62088 SACD Stereo - - 12 Kei Akagi Trio Viewpoint One Voice VAGV-0001 SACD Stereo - - 13 Kei Akagi Palette One Voice VAGV-0002 SACD Stereo - - 14 Kei Akagi Trio A Hint of You One Voice VAGV-1001 SACD Stereo - CD Audio 15 Mika Akiyama Dutilleux piano sonata / 3 préludes, Barber piano Lyrinx LYR-2220 SACD Stereo SACD Surround CD Audio sonata 16 Al Qantarah Abballati, Abballati! Songs and sounds in Medieval fonè SACD FONE 001