Contesting the Reproduction of the Heterosexual Regime Geographies of Oppression and Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

" We Are Family?": the Struggle for Same-Sex Spousal Recognition In

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fmrn any type of computer printer, The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reprodudion. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e-g., maps, drawings, &arb) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to tight in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and Mite photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustratims appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell 8 Howell Information and Leaning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 "WE ARE FAMILY'?": THE STRUGGLE FOR SAME-SEX SPOUSAL RECOGNITION IN ONTARIO AND THE CONUNDRUM OF "FAMILY" lMichelIe Kelly Owen A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto Copyright by Michelle Kelly Owen 1999 National Library Bibliothiique nationale l*B of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services sewices bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. -

Public Accounts of the Province Of

. PUBLIC ACCOUNTS, 1993-94 9 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Hon. Elmer Buchanan, Minister DETAILS OF EXPENDITURE Voted Salaries and Wages ($88,843,852) Temporary Help Services ($1 ,209,981 ): Kelly Temporary Help Services, 56,227; Management Board Secretariat, 928,847; Pinstripe Personnel Inc., 85,064; Accounts under $44,000—139,843. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($413,955): Environment and Energy, 136,421 ; Management Board Secretariat, 277,534. Employee Benefits ($22,051 ,583) Payments for: Canada Pension Plan, 1,513,735; Dental Plan, 856,975; Employer Health Tax, 1,864,594; Group Life Insurance, 191,847; Long Term Income Protection, 1,043,560; Public Service Pension Fund, 6,498,417; Supplementary Health and Hospital Plan, 951,845; Unemployment Insurance, 2,865,580; Unfunded Liability—Public Service Pension Fund, 2,635,782. Other Benefits: Attendance Gratuities, 550,233; Death Benefits, 13,494; Early Retirement Incentive, 899,146; Maternity Leave Allowances, 482,518; Severance Pay, 1,402,869; Miscellaneous Benefits, 92,951 Workers' Compensation Board, 286,515. Payments to Other Ministries ($91 ,549): Management Board Secretariat, 71 ,951 ; Accounts under $44,000—19,598. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($190,027): Accounts under $44,000—190,027. Travelling Expenses ($3,108,328) Hon. Elmer Buchanan, 3,603; P. Klopp, 2,392; R. Burak, 8,212; P.M. Angus, 12,779; D. Beattie, 17,484; B.T. Bell, 8,273; P.K. Blay, 15,244; R. Brown, 9,130; P.J. Butler, 12,842; R.J. Butts, 8,355; L.L. Davies, 9,353; S.J. Delafield, 9,726; E.J. -

Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario for the Year Ended March

. PUBLIC ACCOUNTS, 1992-93 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND FOOD Hon. Elmer Buchanan, Minister DETAILS OF EXPENDITURE Voted Salaries and Wages ($95,497,831) Temporary Help Services ($586,172): Pinstripe Personnel Inc., 136,079; Tosi Placement Sevices Inc., 47,052; Management Board, 155,579; Accounts under $44,000—247,462. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries/Agencies ($704,085): Environment, 236,434; Management Board, 467,651 Employee Benefits ($18,120,827) Payments for: Canada Pension Plan, 1 ,479,777; Group Life Insurance, 207,201 ; Long Term Income Protection, 1 ,026,41 1 ; Employer Health Tax 1 ,949,395; Supplementary Health and Hospital Plan, 859,661; Dental Plan, 736,624; Public Service Pension Fund, 4,427,608; Unfunded Liability- Public Service Pension Fund, 2,595,535; Unemployment Insurance, 2,982,915. Other Benefits: Maternity Leave Allowances, 407,046; Attendance Gratuities, 461 ,643; Severance Pay, 638,187; Death Benefits, 58,262; Miscellaneous Benefits, 2,483. Workers' Compensation Board, 352,814. Payments to Other Ministries ($83,673): Accounts under $44,000—83,673. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($148,408): Accounts under $44,000—148,408. Travelling Expenses ($3,779,958) Hon. Elmer Buchanan, 7,343; P. Hayes, 1,778; P. Klopp, 923; R. Burak, 9,249; P.M. Angus, 11,283; B.T. Bell, 13,223; D.K. Blakely, 8,321; P.K. Blay, 22,051; G. Brown, 8,381; R. Brown 9,108; R.J. Butts, 8,289; LL Davies, 14,023; E.J. Dickson, 12,761; S.M. Dinnissen, 8,812; A. Donohoe, 19,109; R. Duckworth, 8,832; C.R. Dukelow, 12,584; J. -

THORNTON Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Centres MORE THAN a LIVING MEMORIAL to PAST GENERATIONS, THORNTON CEMETERY IS ONE of the CUSTODIANS of OUR COUNTRY’S HISTORY

THORNTON Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Centres MORE THAN A LIVING MEMORIAL TO PAST GENERATIONS, THORNTON CEMETERY IS ONE OF THE CUSTODIANS OF OUR COUNTRY’S HISTORY. This beautiful resting place emulates that of a living city. It reflects the rich mosaic of cultures that have joined together to form the City of Toronto. While still a young cemetery, its value to the community is to chronicle the history of the area’s growth with each passing year. Since 1984, Thornton Cemetery has been providing service to the city of Oshawa, the town of Whitby and neighbouring communities. The award winning landscapes provide stunning beauty and a park-like natural setting for a final resting place. Known as the “cemetery with the be configured or expanded to serve pond,” Thornton has been serving as visitation, service and reception Oshawa, Whitby and neighbouring areas. The efficient layout of the facility communities since 1984. A rolling at Thornton allows families the ability countryside, tranquil pond, and to seamlessly move from funeral colourful flowerbeds enhance the service to cremation without leaving cemetery’s natural, park-like setting. the building. Our newest funeral centre brings The architecture and building materials the possibility of visitation, funeral, of the cemetery’s office, chapel, cremation, interment or memorial cremation centre and mausoleum service and reception together in one reflect the rural and religious buildings stunning building. The chateaux-style of Oshawa’s history. The warm red centre’s timeless design provides an brick of the buildings, for example, is abundance of natural light, a gathering found in many Ontario farm homes, hall which can accommodate 120 and the chapel features stained-glass people and versatile rooms which can works of art. -

R SPIRIT of PROPHECY DAY I MAY 15, 1976

r SPIRIT OF PROPHECY DAY I MAY 15, 1976 Elmshaven, last home of Ellen G. White, at St. Helena. California. Ellen White is in the wheelchair on the top porch (the picture was taken after she broke her hip) and her son William is standing beside the steps downstairs. Arthur L. White, Secretary of the Board A tower of Ellen G. White books — 70 in of Trustees, White Estate, and grandson all — stacked on the floor of the White of Ellen G. White, steadies the stack, Estate vault in Washington, D.C. Included which almost matches his 5 feet 7 inches are most of the current volumes. height. The "Big Bible" held in vision by Ellen White is in view at the left. "Let's get acquainted with the Spirit of Prophecy writings". L _..1 Items from the Canadian Union Office The doors of the new Canadian Union Canadian Union Conference Conference Office were officially open to the public April 13, 3 - 7 p.m. Many Open House people from the community responded to the invitation to visit the office. Alderman Allan C. Pilkey represented City Hall in the absence of the mayor. In his reflections of the Seventh-day Ad- ventist Church and Kingsway College representing those who are not members NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS of the church he said that the church is known as a well-respected organization in the community doing a fine and re- SEVENTH- DAY r DVENTIST CHURCH spectable work. Mr. Walter Beath, chairman of the IN CANADA Durham Region Council, said that there are three things in society that keep changing — government, education and LAST religion. -

Students, He Said the Appar- Backler Pointed out That Second Year Physical in Excess of the Boiling Poin^ Burner

Y.) * \ expo' ents < s e s . J. ga by KEVIN NARBAWAY ing the chemical carbon tetra- the thermometer spilled out examination. These proced- Myszkowski said this ac- fore concentration levels would Chronicle Staff V_^ chloride. The substance super- and began to vaporize on the ures were not followed. cident was no fault of the be low. heated, meaning it was heated open flame of the bunsen "Nobody was affected students, he said the appar- Backler pointed out that Second year physical in excess of the boiling poin^ burner. by said teacher atus being used was 'new and they have had previous ex- chemistry students may have it," the and extreme pressure was According to Jim Brady, Bob Myszkowski. He acted differently.* perience with mercury spil- been exposed to a combination produced. personnel officer and head of explained that in order for When asked about the lage and no one has shown of carbon tetrachloride and used the t* ^The thermometer Durham College safety carbon tetrachloride to be danger of vaporized mercury, . signs of mercury poisoning. mercury, both potentially le- for measuring the temperature committee, the proper pro- dangerous, of thal large amounts Tony Backler, chemistry de- Both mercury and carbon carcinogens when in a of the chemical was forced cedures to follow when toxic the substance would have to gaseous partment head replied, "One tetrachloride are easily ab- form, upwards by this pressure, fumes are in the air, are to be vaporized. would be to there The hesitant say sorbed through the respira- students were con- allowing vaporized 'carbon evacuate the room, call the "The levels would have was no danger," but he added tory tract or the skin and their ducting an experiment in mol- tetrachloride to escape into fire department and take the to be extremely high to present that only a small amount of effects are often crippling. -

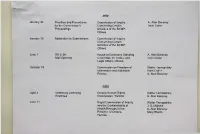

The Original Archival Index of Submissions

1978 January 30 Priorities and Procedures Commission of Inquiry A. Alan Borovoy for the Commission's Concerning Certain Irwin Cotier Proceedings Activities of the RCMP, Ottawa January 30 Addendum to Submissions Commission of Inquiry Concerning Certain Activities of the RCMP, Ottawa June 1 Bill C-26 House of Commons Standing A. Alan Borovoy Mail Opening Committee on Justice and Irwin Cotier Legal Affairs, Ottawa October 19 Commission on Freedom of Walter Tarnopolsky Information and Individual Irwin Cotier Privacy A. Alan Borovoy 1979 April 3 Veterinary Licensing Ontario Human Rights Walter Tarnopolsky Practices Commission, Toronto A. Alan Borovoy Royal Commission of Inquiry Walter Tarnopolsky into the Confidentiality of J. S. Midanik Health Records in the A. Alan Borovoy Province of Ontario, Mary Eberts Toronto October 3 Public Disclosure and Commission of Inquiry Walter Tarnopolsky the Official Secrets Concerning Certain Irwin Cotier Act Activities of the RCMP, A. Alan Borovoy Ottawa October 3 Emergency Powers Commission of Inquiry Irwin Cotier and the War Measures Concerning Certain Walter Tarnopolsky Act Activities of the RCMP, A. Alan Borovoy Ottawa 1980 February 19 Bill 201 Committee on Neighbourhoods, A. Alan Borovoy Police Complaints Housing, Fire and Legislation Machinery City of Toronto March 12 Contact School Investigation Metropolitan Toronto Board J. S. Midanik of Commissioners of Police Walter Pitman A. Alan Borovoy Allan Strader May 14 RCMP Wrongdoing Hon. Robert Kaplan Walter Tarnopolsky Solicitor General of Pierre Berton Canada, Ottawa Dalton Camp T. C. Douglas David Lewis Huguette Plamandon Ed Ratushny Daniel G. Hill A. Alan Borovoy Allan Strader July 2 Submissions of Commission Commission of Inquiry A. -

Two Schools May Soon Become

$1.00 www.oshawaexpress.ca “Well Written, Well Read” Vol 4 No 31 Wednesday, May 27, 2009 Board considering City has consolidation of schools no say on Two schools harbour By Lindsey Cole may soon The Oshawa Express Boats floating casually become along the harbourfront. Families walking along a boardwalk, watching as the ships roll in and out. Colin Carrie one It’s a picturesque scene Oshawa MP that some are saying will be By Katie Strachan no more thanks to a decision by Canada’s The Oshawa Express Transport Minister John Baird to create a Canada Port Authority (CPA) in Oshawa. This It could be another bout of See FEDS Page 8 bad news for Oshawa schools. Just shy of one year after the Durham District Catholic School Board (DDCSB) made the decision to close six of Police get the school system’s elementary schools, the Durham District School Board (DDSB) is now looking at the pos- sible consolidation of two high schools in Oshawa, caus- results ing one to close. Dr. FJ Donevan Collegiate Institute and Eastdale Collegiate Vocational Institute (CVI) may be forced to consolidate after the board makes its decision, which downtown won’t likely come until next year. Durham Regional Police seem to be mak- The reasoning behind the possible joining can be ing an impact in central Oshawa. attributed to declining enrolment. Police have been increasing foot patrols, The City of Oshawa has experienced unprecedented created strong partnerships with local mer- residential development in north Oshawa, which led to a chants and downtown homeowners and are decrease in student enrolment in east Oshawa. -

Winter OFL Action Report

2015 OFL Convention Play-By-Play on Pages 10-13 ACTION REPORT VOL. 6 NO. 1 ONTARIO FEDERATION OF LABOUR WINTER 2016 President Chris Buckley P.5 THOUSANDS STAND UP FOR STEEL ARCHIVES SPECTATOR HAMILTON PHOTO: Secretary-Treasurer OFL NEWS Patty Coates Letter from OFL President Chris Buckley ..............................................................................3 For President Chris Buckley, Unity and Solidarity are Priority Number One ............................14 Patty Coats Keeps One Fist in the Air and the Other on the Ledger ......................................14 Ahmad Gaied Seeks to Give Voice to the Precarious Generation ..........................................14 Officers Receive a Little Devine Intervention .......................................................................15 Labour & Human Rights Dates ..........................................................................................18 Upcoming Events .............................................................................................................19 Executive Vice-President THE ONTARIO WE WANT MEET THE OFL OFFICERS ON THE COVER: The OFL Poises to Launch Province-Wide Campaign for Fairness at Work ...4 Thousands Rally in Hamilton to Defend Good Jobs, Pensions and Canadian Manufacturing ....5 Ahmad Gaied Ontario Budget Talks Met with Protest .................................................................................6 OFL Calls on Ontario to Fund Historic Anti-Racism Secretariat ..............................................7 ACTION REPORT Common -

Public Accounts of the Province Of

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS, 1991-92 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND FOOD Hon. Elmer Buchanan, Minister DETAILS OF EXPENDITURE Voted Salaries and Wages ($99,786,639) Temporary Help Services ($767,001 ): County of Huron, 49,389; DGS Information Consultants, 54,865; Management Board, 169,445; The People Bank, 71,761; Pinstripe Personnel Inc., 115,934; Accounts under $44,000—305,607. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries/Agencies ($654,913): Environment, 220,726; Management Board, 434,187. Employee Benefits ($18,667,381) Payments for: Canada Pension Plan, 1,521,714; Group Life Insurance, 187,023; Long Term Income Protection, 884,454; Employer Health Tax, 1,945,250; Supplementary Health and Hospital Plan, 765,097; Dental Plan, 643,115; Public Service Pension Fund, 6,284,737; Unfunded Liability- Public Service Pension Fund, 2,328,832; Unemployment Insurance, 2,842,379. Other Benefits: Maternity Leave Allowances, 234,399; Attendance Gratuities, 1 17,217; Severance Pay, 471 ,973; Voluntary Exit Options, 7,816. Workers' Compensation Board, 394,295. Payments to Other Ministries ($150,867): Accounts under $44,000—1 50,867. Less: Recoveries from Other Ministries ($1 1 1 ,787): Accounts under $44,000—1 1 1 ,787. Travelling Expenses ($4,774,052) Hon. Elmer Buchanan, 6,290; P. Hayes, 2,023; P. Klopp, 718; R. Burak, 7,358; D.K. Alles, 8,304; J.L Anderson, 9,420; D. Beattie, 14,317; B.T. Bell, 18,611; D.K. Blakely, 8,053; P.K. Blay, 31,531; R. Brown, 9,824; D. Busher, 10,996; R.J. Butts, 8,280; K.D. Cameron, 9,913; R.T. -

L'unité Des Enquêtes Spéciales Rédigé À L'intention Du Procureur Général De L'ontario Par L'honorable George W

L’Unité des enquêtes spéciales : un exemple à ne pas suivre Alexandre Popovic Coalition contre la répression et les abus policiers 21 février 2013 Table des matières Avant-propos....................................................................................................................... 3 Les sources .......................................................................................................................... 7 Origines du l’UES ............................................................................................................. 13 Une législation bâclée ....................................................................................................... 28 Les directeurs de l’UES .................................................................................................... 48 D’un ministère à l’autre : blanc bonnet, bonnet blanc ? ................................................... 64 Le parent pauvre de la province ........................................................................................ 85 Manque d’indépendance face à la police .......................................................................... 97 Interminables débats sur la juridiction ............................................................................ 111 Qu’est-ce qu’une blessure grave ? .................................................................................. 126 Otage de la bonne volonté des policiers ......................................................................... 136 Se trainer les pieds avant -

Exciting Christmas Ideas

Exciting Christmas Ideas Gifts that show you care... ... and keep on giving Two of the moot important books ever written for thaie involved in law enforrement STREET SURVNAL Tactics for Anned Encounters Positive tactics designed to master real-life situations. 403 pages of photos, diagrams, and the hard lessons of real experience. $46.95 THE TACTICAL EDGE Surviving High Risk Patrol Advanced material ideal for academy and departmental training programs and all law enforcement professionals. 544 pages with over 750 photos and drawings. $58.95 Available in Canada from Training and upgrading material for the Law Enforcement Community 12A-4981 Hwy.7 East, Ste.254, Markham, Ontario, L3R 1N1 - (416)293-2631 Marketing Ultimate SUlvivors (Video) $75.95 0 Five Minute Policeman $13.70 Surviving Edged Weapons (Video) $65.95 0 Boss Talk $13.70 Tactical Edge $58.95 0 CaseManager (Computer Softwear) $310.00 Street Survival $46.95 0 Case Manager (Single User Version) $150.00 One Year Subscription (10 Issues) to Blue L ine Magazine $25.00 (G.S.T. Included) Sub Total G.S.T. Name: Address: Ont Sales Tax Municipality ______ Province _____ Postal Code: ____ Total 7% Goods & SeIVices Tax Extra Phone: (._<-) _______ No Ontario Sales Tax on Books Prices include Shipping & Handling end Invoice with product (Available to Paid Subscribers, Law Enforcmenet Agencies, and Educational Facilities Only) Plea e charge my VISA or MasterCard account # Exp. / ---------------~~--- Cheque Enclo cd Signature: November 1991 COVER STORY IN THIS ISSUE FEATURES Cover Story 3 Commentary: City of Angels -Robert Hotston 4 Letters To The Editor 5 Defensive Tactics: Craig Best 6 The R.I.D.E.