Joint Use of Track by Electric Railways and Railroads: Historic View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Return to the High Iron: the Operation and Interpretation of Mainline Steam Excursions in the United States

! ! RETURN TO THE HIGH IRON: THE OPERATION AND INTERPRETATION OF MAINLINE STEAM EXCURSIONS IN THE UNITED STATES by Joseph M. Bryan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History Middle Tennessee State University August 2015! ! ! ! Thesis Committee: Dr. Carroll Van West, Chair Dr. Susan Myers-Shirk ! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my family for their unending love and support throughout this entire project. I would like to especially thank my mother for being such an incredible role model whom I look up to everyday. I would also like to thank Dr. Carroll Van West and Dr. Susan Myers-Shirk for their guidance and patience in making this idea become a reality. I would like to thank the following individuals and organizations for their assistance in this project: Ron Davis, Fran Ferguson, Cheri George, Trevor Lanier, Jennifer McDaid, John Nutter, Deena Sasser, Jim Wrinn, the Norfolk & Western Historical Society, Norfolk Southern Corporation, the Southern Railway Historical Association and the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum. Their invaluable support and materials are very much appreciated. Finally, I would like to thank the staff and board of directors of the Virginia Museum of Transportation for deciding to take a chance and restore the Norfolk & Western Class J No. 611 steam locomotive to operable condition and, as a result, providing me with an incredible thesis topic. ii!! ABSTRACT The steam locomotive is one of the most recognizable artifacts from industrial history. After their demise in the mid-twentieth century, those that were not cut up for scrap found homes at new transportation museums and with railroad historical organizations. -

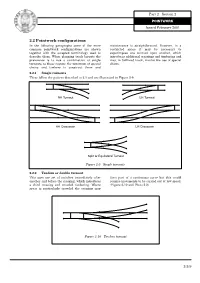

2.2 Pointwork Configurations in the Following Paragraphs Some of the More Maintenance Is Straightforward

Part 2 Section 2 POINTWORK Issued February 2001 2.2 Pointwork configurations In the following paragraphs some of the more maintenance is straightforward. However, in a common pointwork configurations are shown restricted space it may be necessary to together with the accepted terminology used to superimpose one turnout upon another, which describe them. When planning track layouts the introduces additional crossings and timbering and preference is to use a combination of single may, in bullhead track, involve the use of special turnouts as these require the minimum of special chairs. chairs and timbers to construct them and 2.2.1 Single turnouts These follow the pattern described in 2.1 and are illustrated in Figure 2-9. RH Turnout LH Turnout RH Crossover LH Crossover Split or Equilateral Turnout Figure 2-9 Single turnouts 2.2.2 Tandem or double turnout This uses one set of switches immediately after form part of a continuous curve but this would another and before the crossing, which introduces require movements to be carried out at low speed. a third crossing and crowded timbering. Where (Figure 2-10 and Photo 2.2) space is particularly crowded the crossing may Figure 2-10 Tandem turnout 2-2-9 2.2.3 Three-throw turnout Photo 2.2 A double tandem turnout leading off from a double There is a nomenclature problem here slip at Stowmarket Goods Yard. as the 3-throw yields the same outcome (NRM Windwood Collection GE1005) as the double turnout. It uses a left hand and a right hand set of switches that are superimposed to divide three ways together in symmetrical form. -

April / May 2018 Metrolink Matters

5 6 APRIL | MAY 2018 LOVE FOR BUILDING THINGS AS A GIRL TURNS INTO A CAREER ON THE RAILROAD ANGELS EXPRESS IS BACK BEGINNING APRIL 2! BLOG METROLINK MATTERS GOES DIGITAL WITH NEW BLOG an’t get enough of Metrolink Matters? Passengers and Elizabeth Lun presenting Metrolink’s structures condition and rehabilitation program to Metrolink Board Members. Lun inside the Santa Fe 3751 steam engine during the Grand stakeholders can now view the latest Metrolink news and Opening Ceremony of the Vincent Grade / Acton station. information on the official new blog, Metrolink Matters. The blog is designed to provide readers with up-to-date or Elizabeth Lun, a childhood passion for building things has turned how working at Metrolink has impacted her professionally and personally. information on a user-friendly, easy-to-access digital platform. into a career overseeing the design and construction of projects that She noted, “My work and personal life balance has improved substantially C F are ushering in a new future for the Metrolink commuter rail system. since joining Metrolink.” Lun added, “I have a deep appreciation for my Metrolink Matters will offer new weekly articles ranging from Trains will operate on the Orange County Line to all weekday home games that job, which allows me to exercise my knowledge and skill while providing Agency news and safety reminders to community outreach start at 7:07 p.m. and on Friday night games on the Inland Empire-Orange As I went through college and early career, I went into transportation me freedom to pursue other passions outside of work. -

Metro Rail Design Criteria Section 10 Operations

METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 OPERATIONS METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 / OPERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 10.1 INTRODUCTION 1 10.2 DEFINITIONS 1 10.3 OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE PLAN 5 Metro Baseline 10- i Re-baseline: 06/15/10 METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 / OPERATIONS OPERATIONS 10.1 INTRODUCTION Transit Operations include such activities as scheduling, crew rostering, running and supervision of revenue trains and vehicles, fare collection, system security and system maintenance. This section describes the basic system wide operating and maintenance philosophies and methodologies set forth for the Metro Rail Projects, which shall be used by designer in preparation of an Operations and Maintenance Plan. An initial Operations and Maintenance Plan (OMP) is developed during the environmental phase and is based on ridership forecasts produced during this early planning phase of a project. From this initial Operations and Maintenance plan, headways are established that are to be evaluated by a rail operations simulation upon which design and operating headways can be established to confirm operational goals for light and heavy rail systems. The Operations and Maintenance Plan shall be developed in order to design effective, efficient and responsive transit system. The operations criteria and requirements established herein represent Metro’s Rail Operating Requirements / Criteria applicable to all rail projects and form the basis for the project-specific operational design decisions. They shall be utilized by designer during preparation of Operations and Maintenance Plan. Any proposed deviation to Design Criteria cited herein shall be approved by Metro, as represented by the Change Control Board, consisting of management responsible for project construction, engineering and management, as well as daily rail operations, planning, systems and vehicle maintenance with appropriate technical expertise and understanding. -

Rio Grande Station Cape May County, NJ Name of Property County and State 5

NPS Form 10-900 JOYf* 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) !EO 7 RECE!\ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service n m National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ii:-:r " HONAL PARK" -TIO.N OFFICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategones from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form I0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________________ historic name R'Q Grande Station____________________________________ other names/site number Historic Cold Spring Village Station______________________ 2. Location street & number 720 Route 9 D not for publication city or town Lower Township D vicinity state New Jersey_______ code NJ county Cape May_______ code 009 zip code J5§204 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Q nomination G request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S meets D doss not meet the National Register criteria. -

Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road

Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road BALTIMORE AND OHIO RAIL ROAD. Spec. law of MD, February 28, 1827 Trackage, June 30, 1918: 2315.039 mi. First main track 774.892 mi. Second and other main tracks 1580.364 mi. Yard track and sidings Equipment Steam locomotives 2,242 Other locomotives 9 Freight cars 88,904 Passenger cars 1,243 Floating equipment 168 Work equipment 2,392 Miscellaneous 10 Equipment, leased Steam locomotives 16 to Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Steam locomotives 1 to Little Kanawha Railroad Steam locomotives 4 to Long Fork Railway Steam locomotives 1 to Morgantown and Kingwood Steam locomotives 5 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Steam locomotives 6 to The Sharpsville Railroad Steam locomotives 30 to Staten Island Rapid Transit Steam locomotives 158 from Toledo and Cincinnati Freight cars 4 to Long Fork Railway Freight cars 5 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Freight cars 5,732 from Toledo and Cincinnati Freight cars 976 from Mather Humane Stock Transportation Co. Passenger cars 1 to Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Passenger cars 3 to Long Fork Railway Passenger cars 4 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Passenger cars 1 to The Sharpsville Railroad Passenger cars 110 from Toledo and Cincinnati Work equipment 2 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Work equipment 57 to Staten Island Rapid Transit Miscellaneous 2 from Toledo and Cincinnati Miscellaneous 1 from Baltimore and Ohio in Pennsylvania Miscellaneous 7 from Baltimore and Ohio Southwestern The Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road controls the following companies: -

Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives

REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the national archives 1 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Peter F. Brauer 2010 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records relating to railroads in the cartographic section of the National Archives / compiled by Peter F. Brauer.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2010. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; no 116) includes index. 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Cartographic and Architectural Branch — Catalogs. 2. Railroads — United States — Armed Forces — History —Sources. 3. United States — Maps — Bibliography — Catalogs. I. Brauer, Peter F. II. Title. Cover: A section of a topographic quadrangle map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey showing the Union Pacific Railroad’s Bailey Yard in North Platte, Nebraska, 1983. The Bailey Yard is the largest railroad classification yard in the world. Maps like this one are useful in identifying the locations and names of railroads throughout the United States from the late 19th into the 21st century. (Topographic Quadrangle Maps—1:24,000, NE-North Platte West, 1983, Record Group 57) table of contents Preface vii PART I INTRODUCTION ix Origins of Railroad Records ix Selection Criteria xii Using This Guide xiii Researching the Records xiii Guides to Records xiv Related -

Northeast Corridor Chase, Maryland January 4, 1987

PB88-916301 NATIONAL TRANSPORT SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT REAR-END COLLISION OF AMTRAK PASSENGER TRAIN 94, THE COLONIAL AND CONSOLIDATED RAIL CORPORATION FREIGHT TRAIN ENS-121, ON THE NORTHEAST CORRIDOR CHASE, MARYLAND JANUARY 4, 1987 NTSB/RAR-88/01 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2.Government Accession No. 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB/RAR-88/01 . PB88-916301 Title and Subtitle Railroad Accident Report^ 5-Report Date Rear-end Collision of'*Amtrak Passenger Train 949 the January 25, 1988 Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight -Performing Organization Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor, Code Chase, Maryland, January 4, 1987 -Performing Organization 7. "Author(s) ~~ Report No. Performing Organization Name and Address 10.Work Unit No. National Transportation Safety Board Bureau of Accident Investigation .Contract or Grant No. Washington, D.C. 20594 k3-Type of Report and Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Iroad Accident Report lanuary 4, 1987 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 1*+.Sponsoring Agency Code 15-Supplementary Notes 16 Abstract About 1:16 p.m., eastern standard time, on January 4, 1987, northbound Conrail train ENS -121 departed Bay View yard at Baltimore, Mary1 and, on track 1. The train consisted of three diesel-electric freight locomotive units, all under power and manned by an engineer and a brakeman. Almost simultaneously, northbound Amtrak train 94 departed Pennsylvania Station in Baltimore. Train 94 consisted of two electric locomotive units, nine coaches, and three food service cars. In addition to an engineer, conductor, and three assistant conductors, there were seven Amtrak service employees and about 660 passengers on the train. -

Federal Pacific Electric (FPE) Stab-Lok Breakers and Panelboards

Federal Pacific Electric (FPE) Stab-Lok Breakers and Panelboards HSB, part of Munich Re, is a What is the best course of action when discovered? technology-driven company built on a foundation of specialty insurance, engineering and technology, all Federal Pacific Electric Company (FPE) manufactured many electrical products working together to drive innovation while in business including a panelboard and breaker line called Stab-Lok. The in a modern world. Stab-Lok products are no longer manufactured, but millions had been installed in residential and commercial buildings between 1950 and 1985. The purpose of the breaker is to protect the building from fire in the event of an electrical circuit abnormality. The Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) investigated many reports in 1982 of Stab-Lok breakers failing to trip as required by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) testing standards. The CPSC did not have the funding to further investigate this problem or arrive at a definitive conclusion. Tests by the CPSC and independent consulting engineers concluded that certain Stab-Lok breakers do not trip according to UL requirements and in some cases, can jam in the “on” position. In addition, overheating problems have been found within the panelboard internal bus connections. Unfortunately, this information surfaced after many Stab-Lokinstallations were completed and had been in service for years. In 2002, a New Jersey class-action lawsuit decided that the manufacturer of the Stab-Lok breakers committed fraud over many years in issuing UL labels to products they knew did not meet the UL testing requirements. HSB Page 2/2 Federal Pacific Electric (FPE) Stab-Lok Breakers and Panelboards The National Electrical Code requires that all installed products must be listed and labeled by an independent testing agency to be acceptable for the intended use. -

Interstate Commerce Commission Washington

INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION WASHINGTON REPORT NO. 3374 PACIFIC ELECTRIC RAILWAY COMPANY IN BE ACCIDENT AT LOS ANGELES, CALIF., ON OCTOBER 10, 1950 - 2 - Report No. 3374 SUMMARY Date: October 10, 1950 Railroad: Pacific Electric Lo cation: Los Angeles, Calif. Kind of accident: Rear-end collision Trains involved; Freight Passenger Train numbers: Extra 1611 North 2113 Engine numbers: Electric locomo tive 1611 Consists: 2 muitiple-uelt 10 cars, caboose passenger cars Estimated speeds: 10 m. p h, Standing ft Operation: Timetable and operating rules Tracks: Four; tangent; ] percent descending grade northward Weather: Dense fog Time: 6:11 a. m. Casualties: 50 injured Cause: Failure properly to control speed of the following train in accordance with flagman's instructions - 3 - INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION REPORT NO, 3374 IN THE MATTER OF MAKING ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION REPORTS UNDER THE ACCIDENT REPORTS ACT OF MAY 6, 1910. PACIFIC ELECTRIC RAILWAY COMPANY January 5, 1951 Accident at Los Angeles, Calif., on October 10, 1950, caused by failure properly to control the speed of the following train in accordance with flagman's instructions. 1 REPORT OF THE COMMISSION PATTERSON, Commissioner: On October 10, 1950, there was a rear-end collision between a freight train and a passenger train on the Pacific Electric Railway at Los Angeles, Calif., which resulted in the injury of 48 passengers and 2 employees. This accident was investigated in conjunction with a representative of the Railroad Commission of the State of California. 1 Under authority of section 17 (2) of the Interstate Com merce Act the above-entitled proceeding was referred by the Commission to Commissioner Patterson for consideration and disposition. -

Electric Railway Engineering

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY Volume Class Book i^LL fTir^fa '"-^alljf' Return this book on or before the Latest Date stamped below. A charge is made on all overdue ^°°^^S- U. of I. Library ^tMK xb iS'- ^^^, i€ i^l; .^!^ 1762S-S ELECTRK^ RAILA\ AY ENGINEERING ELECTEIC KAILWAY ENGINEERING BY C. FRANCIS HARDING, E. E. professor, electrical engineering; director, electrical laboratories, purdue universitt; associate American institute electrical engineers; asso- ciate AMERICAN electric RAILWAY ASSOCIATION ; MEMBER SOCIETY FOR promotion OF ENGINEERING EDUCATION McGRAW-HILL BOOK COMPANY 239 WEST 39TH STREET. NEW YORK 6 BOUVERIE STREET, LONDON, E. C. 1911 Copyright, 1911 BY McGraw-Hill Book Company Prhited and Eleclrolyped by The Maple Press York. Fa. PREFACE. To students in technical universities who wish to specialize in the subject of electrical railway engineering and to those who understand the fundamental principles of electrical engineering and are interested in their application to electric railway practice it is hoped that this book may be of value. While it is planned primarily for a senior elective course in a technical university, it does not involve higher mathematics and should therefore be easily understood by the undergraduate reader. The volume does not purport to present any great amount of new material nor principles, but it does gather in convenient form present day theory and practice in all important branches of electric railway engineering. No apology is deemed necessary for the frequent quotations from technical papers and publications in engineering periodicals, for it is only from the authorities and specialists in particular phases of the profession that the most valuable information can be obtained, and it is believed that a thorough and unprejudiced summary of the best that has been written upon the various aspects of the subject will be most welcome when thus combined into a single volume. -

Staten Island Railway Railway Timetable

Effective Winter 2016 – 2017 MTA Staten Island Railway Railway Timetable ✪ NEW: ARTHUR KILL STATION MetroCard® may be purchased at vending machines located at St George terminal and at Tompkinsville station, and is accepted for both entering and leaving the railway at both locations as well. Now more than ever – MTA Staten Island Railway for speed and reliability Reduced-Fare Benefits – If you qualify for reduced fare, you can travel for half fare. You are eligible for reduced-fare benefit if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability with proper identification. Benefits are available (except on peak-hour express buses) with proper identification, including Reduced-Fare MetroCard or Medicare card (Medicaid cards do not qualify). Children – The subway, SIR, local, Limited-Stop, and +SelectBusService buses permit up to three children, 44 inches tall and under, to ride free when accompanied by an adult paying full-fare. Express buses permit one child, two years old and under, to ride free when carried in the lap of a fare-paying adult. Holiday Service – On Martin Luther King Day, Columbus Day, Veterans Day, Election Day, and the Day after Thanksgiving, SIR operates a Weekday Schedule. When New Years Day, Presidents Day, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving Day, and Christmas Day are celebrated Tuesday through Friday, SIR operates a Saturday Schedule; however, if these holidays are celebrated on Saturday, Sunday or Monday, SIR operates a Sunday Schedule. SIR will operate early departure “get-a-way” schedules on the evening before select holidays. Please refer to Service Information posters for details.