Daniel Barenboim Reith Lectures 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Notes | Yannick and Manny

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, November 29, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, November 30, at 8:00 Saturday, December 1, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Emanuel Ax Piano Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83 I. Allegro non troppo II. Allegro appassionato III. Andante—Più adagio—Tempo I IV. Allegretto grazioso—Un poco più presto Intermission Brown Perspectives United States premiere Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 I. Allegro maestoso II. Poco adagio III. Scherzo: Vivace IV. Finale: Allegro This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Elia D. Buck and Caroline B. Rogers. The November 29 concert is also sponsored by the Louis N. Cassett Foundation. The November 30 concert is sponsored by Alexandra Edsall and Robert Victor. The December 1 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us following the November 30 and December 1 concerts for a free Organ Postlude featuring Peter Richard Conte. Brahms Prelude, from Prelude and Fugue in G minor Brahms Fugue in A-flat minor Dvořák/transcr. Conte Humoresque, Op. 101, No. 7 Widor Toccata, from Organ Symphony No. 5 in F minor, Op. 42, No. 1 The Organ Postludes are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Itunes Store and Spotify Recordings

A+ Music Memory 2016-2017 iTunes Store and Spotify Recordings Bach Pachelbel Canon and Other Baroque Favorites, track 12, Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV1067: Badinerie (James Galway, Zagreb Soloists & I Solisti di Zagreb, Universal International BMG Music, 1978). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/pachelbel-canon-other- baroque/id458810023 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/4bFAmfXpXtmJRs2t5tDDui Bartók Bartók: Hungarian Pictures – Weiner: Hungarian Folk Dance – Enescu: Romanian Rhapsodies, track 2, Magyar Kepek (Hungarian Sketches), BB 103: No. 2. Bear Dance (Neeme Järvi & Philharmonia Orchestra, Chandos, 1991). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/bartok-hungarian-pictures/id265414807 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/5E4P3wJnd2w8Cv1b37sAgb Beethoven Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 8, 14, 23 & 26, track 6, Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 13 – “Pathétique,” III. Rondo (Allegro), (Alfred Brendel, Universal International Music B.V., 2001) iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/beethoven-piano-sonatas- nos./id161022856 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/2Z0QlVLMXKNbabcnQXeJCF Brahms Best of Brahms, track 11, Waltz No. 15 in A-Flat Minor, Op. 59 [Note: This track is mis-named: the piece is in A-Flat Major, from Op. 39] (Dieter Goldmann, SLG, LLC, 2009). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/best-of-brahms/id320938751 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/1tZJGYhVLeFODlum7cCtsa A+ Mu Me ory – Re or n s of Clarke Trumpet Tunes, track 2, Suite in D Major: IV. The Prince of Denmark’s March, “Trumpet Voluntary” (Stéphane Beaulac and Vincent Boucher (ATMA Classique, 2006). iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/album/trumpet-tunes/id343027234 Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/track/7wFCg74nihVlMcqvVZQ5es Delibes Flower Duet from Lakmé, track 1, Lakmé, Act 1: Viens, Mallika, … Dôme épais (Flower Duet) (Dame Joan Sutherland, Jane Barbié, Richard Bonynge, Orchestre national de l’Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Decca Label Group, 2009). -

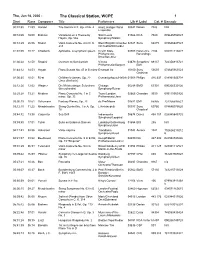

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Jun 18, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 11:59 Handel Trio Sonata in F, Op. 2 No. 4 Heinz Holliger Wind 00341 Denon 7026 N/A Ensemble 00:14:2918:00 Brahms Variations on a Theme by Saint Louis 01966 RCA 7920 078635792027 Haydn, Op. 56a Symphony/Slatkin 00:33:29 26:06 Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, K. Stern/English Chamber 02925 Sony 66475 074646647523 218 Orchestra/Schneider 01:01:0528:17 Chadwick Aphrodite, a symphonic poem Czech State 03308 Reference 2104 030911210427 Philharmonic, Recordings Brno/Serebrier 01:30:2212:50 Rossini Overture to Semiramide Vienna 03679 Seraphim/ 69137 724356913721 Philharmonic/Sargent EMI 01:44:1214:53 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 47 in B minor Emanuel Ax 10100 Sony 53635 074645363523 Classical 02:00:3510:51 Bizet Children's Games, Op. 22 Concertgebouw/Haitink 01008 Philips 416 437 028941643728 (Jeux d'enfants) 02:12:2612:02 Wagner Die Meistersinger: Selections Chicago 05288 BMG 63301 090266330126 (for orchestra) Symphony/Reiner 02:25:2833:21 Medtner Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Tozer/London 02666 Chandos 9039 095115903926 minor, Op. 33 Philharmonic/Jarvi 03:00:1910:51 Schumann Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 du Pre/Moore 09531 EMI 65955 724356595521 03:12:1031:22 Mendelssohn String Quintet No. 1 in A, Op. L'Archibudelli 05537 Sony 60766 074646076620 18 Classical 03:44:32 13:38 Carpenter Sea Drift Indianapolis 08678 Decca 458 157 028945845725 Symphony/Leppard 03:59:4017:01 Tubin Suite on Estonian Dances Lubotsky/Gothenburg 01654 BIS 286 N/A Symphony/Jarvi 04:17:41 02:56 Halvorsen Valse caprice Trondheim 01943 Aurora 1921 702626219212 Symphony/Ruud 6 04:21:3738:22 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

The History www.fazioli.com The History www.fazioli.com 1944–1977 Paolo Fazioli was born in Rome in 1944, into a family of furniture makers. From a very early age he demonstrated a gift for music and a keen interest in the piano. He consequently started taking piano lessons and continued his piano studies thorough his high school and university years, during which he developed a keen interest in the piano construction technology, broadening his knowledge by visiting manufacturing and restoration workshops and reading the most authoritative literature on the subject. In 1969, he graduated from the University of Rome with a degree in Mechanical Engineering and in 1971 he received a degree in piano performance from the G. Rossini Conservatory in Pesaro, under the guidance of Maestro Sergio Cafaro. At the same time, he earned a Master’s degree in Music Composition at the St Cecilia Academy in Rome, where he studied under the composer Boris Porena. In the meantime, his elder brothers took over the family business, manufacturing office The FAZIOLI family in 1947 furniture and exporting it throughout the world under the brand of MIM (Mobili Italiani Moderni). The Turin factory specialised in the production of metal furniture, while the Sacile factory (in the province of Pordenone) manufactured wood furniture using rare and exotic woods such as teak, mahogany and rosewood. 1944–1977 Paolo Fazioli joined the company after graduation, honing his management skills as a production planning manager first in Rome and then at the Turin factory, while at the same time developing his expertise in wood processing. -

4961168-37E111-714439855628.Pdf

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) Daniel Levy, piano 24 PRELUDES OP. 11 01. No.1 in C Major: Vivace 0’ 57” 02. No.2 in A Minor: Allegretto 1’ 57” 03. No.3 in G Major: Vivo 1’ 02” 04. No.4 in E Minor: Lento 2’ 00” 05. No.5 in D Major: Andante cantabile 1’ 46” 06. No.6 in B Minor: Allegro 0’ 56” 07. No.7 in A Major: Allegro assai 1’ 28” 08. No.8 in F Sharp Minor: Allegro agitato 1’ 40“ 09. No.9 in E Major: Andantino 1’ 43” 10. No.10 in C Sharp Minor: Andante 1’ 26” 11. No.11 in B Major: Allegro assai 2’ 03” 12. No.12 in G Sharp Minor: Andante 1’ 27” 13. No.13 in G Flat Major: Lento 1’ 30” 14. No.14 in E Flat Minor: Presto 1’ 02” 15. No.15 in D Flat Major: Lento 1’ 54” 16. No.16 in B Flat Minor: Misterioso 1’ 49” 17. No.17 in A Flat Major: Allegretto 0’ 40” 18. No.18 in F Minor: Allegro agitato 0’ 56” 19. No.19 in E Flat Major: Affettuoso 2’ 01” 20. No.20 in C Minor: Appassionato 1’ 12” 21. No.21 in B Flat Major: Andante 1’ 23” 22. No.22 in G Minor: Lento 1’ 17” 23. No.23 in F Major: Vivo 0’ 39” 24. No.24 in D Minor: Presto 0’ 55” 25. ÉTUDE IN C MINOR OP. 2, NO. 1 3’ 18” 12 ÉTUDES OP. 8 26. No.1 in C Sharp Minor: Allegro 1’ 43” 27. -

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Foundation

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Foundation Information July/August 2011 President Maestro Kurt Masur honoured Award ceremony in Paris The German Foreign Ministry and the French Ministry of Foreign & European Affairs have chosen Maestro Kurt Masur and Professor Pierre Boulez as winners of the Adenauer- de Gaulle Prize in 2011. On 20 June 2011 the Prize was formally bestowed at a ceremony in the Hôtel de Beauharnais, the Residence of the German Ambassador in Paris, by the two Ministers responsible for Franco- German co-operation, French Europe Minister Laurent Wauquiez and the German friendship. The artistic careers of Pierre Boulez and Kurt Masur – for- Minister of State in the German Fo- med through many years of experience in Germany and France – are an exam- reign Office Dr Werner Hoyer. ple of the creativity and originality which the values of the European commu- nity have produced.” declared Minister of State Dr Hoyer. “In the French con- The Adenauer-de Gaulle Prize, ductor and composer Pierre Boulez and the German conductor Kurt Masur, this which was established on 22 January year we are honouring two personalities who, through their professional as 1988, is a distinction for those people well as private commitment, have made an extraordinary contribution to Fran- who have made an especial contribu- co-German relations. Both have worked tirelessly for many years in the neigh- tion to Franco-German co-operation. It bouring country. Kurt Masur was in charge of the “Orchestre National de France” is named after the former German from 2002 to 2008. Pierre Boulez, who had already conducted in Germany in Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer the 1950s and 1960s, has for many years worked together with the Berlin and the former President of the French Philharmonic Orchestra.” Republic Charles de Gaulle. -

Music – Our Passion

2011 recent releases and highlights for piano Music – Our Passion. Hal Leonard is proud to be exclusive U.S. distributor for the distinguished Munich-based music publisher G. Henle Verlag. Henle Urtext editions are highly regarded for impeccable research of composers’ manuscripts, proofs, first editions and other relevant sources. Henle editions are universally praised for: • authoritative musical accuracy • the world’s highest quality music engraving • insightful critical commentary • helpful fingerings • premium, custom made paper • long-lasting binding for a lifetime of use Among the world’s leading classical pianists who have endorsed, performed and recorded Henle Urtext editions are: Leif Ove Andsnes • Vladimir Ashkenazy • Paul Badura-Skoda • Daniel Barenboim • Alfred Brendel • Rudolf Buchbinder • Philippe Entremont • Marc-André Hamelin • Vladimir Horowitz • Evgeny Kissin • Lang Lang • Elisabeth Leonskaja • Yundi Li • Gerhard Oppitz • Murray Perahia • András Schiff • Grigory Sokolov • Mitsuko Uchida • Lars Vogt REcent Urtext Editions for Piano Urtext editions FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: PIANO ROBERT SCHUMANN: SEVEN are softcover SONATA IN C MINOR, OP. 4 PIANO PIECES IN FUGHETTA unless clothbound is indicated. 51480942 ..................................................... $17.95 FORM, OP. 126 FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: POLONAISE 51480907 ..................................................... $13.95 Search description, IN A-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 53 ROBERT SCHUMANN: THREE contents, editors, REVISED EDITION PIANO SONATAS FOR THE and all available Henle publications -

Müller Vs Schubert in Der Leiermann Brian Chapman ([email protected])

A WINTERREISE HYPOTHETICAL: Müller vs Schubert in Der Leiermann Brian Chapman ([email protected]) In the twenty-four poems of Wilhelm Müller’s Die Winterreise the protagonist gives expression to no fewer than twenty-six questions. According to the ordering of the poems in Franz Schubert’s Winterreise song cycle, the first twenty-four of these questions are scattered among twelve of the first twenty-one songs and are rhetorical in nature, being addressed by the protagonist either to himself or to the world at large. These questions reflect the thoughts and feelings of the jilted lover, being focussed first on self-pity (Nos. 1-13) and then on the desire for death (Nos. 14-23). In the final poem – No.24 Der Leiermann (The Hurdy-Gurdy Man) – there is a total shift in the poetic psychology. Whereas the first twenty-three songs give expression to a self-absorbed psychopathological journey entirely void of human contact – and almost void of any living creature at all save for occasional references to barking dogs, hostile ravens, a fond memory of a lark and nightingale engaged in competitive song, and a portentous crow – No.24 is devoted completely to the woeful plight of someone other than the protagonist. For the first time in the entire cycle, the protagonist focusses on the pathetic situation of another human being – a pitiful, lonely hurdy-gurdy man to whom nobody listens, from whom everyone averts his or her gaze, and whose little plate is always empty as stray dogs growl around him, thus: 24. The Hurdy-Gurdy Man1 Stands an organ-grinder No one likes to hear him, There outside the town, No one looks his way, Plays as best he can though And around the old man Fingers stiff have grown. -

ARTEMIS QUARTET Vineta Sareika, Violin Suyoen Kim, Violin Gregor Sigl, Viola Harriet Krijgh, Cello

ARTEMIS QUARTET Vineta Sareika, violin Suyoen Kim, violin Gregor Sigl, viola Harriet Krijgh, cello Artemis Quartet gives concerts for all great musical centres and international festivals in Europe, the United States, Asia, South America and Australia. Since 2004 the ensemble creates own cycles at the chamber music hall of Berlin Philharmonie, since 2011 at Wiener Konzerthaus (together with Belcea Quartet) and with the beginning of season 2016/2017 at Prince Regent Theatre Munich. Berlin based Artemis Quartet was founded in 1989 at the University of Music Lübeck and is counted among the foremost worldwide quartet formations today. Important mentors have been Walter Levin, Alfred Brendel, the Alban Berg Quartet, the Juilliard Quartet and the Emerson Quartet. Being awarded the first place in ARD competition in 1996 and six months later at‚Premio Borciani’, made the quartet internationally successful. Yet the four initially followed an invitation of the Institute for Advanced Study Berlin in order to enhance their studies as an ensemble and to broaden them in an interdisciplinary exchange with renowned academics. The quartet’s “comeback” happened with its Berliner debut. In 2013, the Beethovenhaus Bonn decorates the quartet as an honorary member for merits of its interpretation of Beethoven’s work. From the beginning the collaboration with musical colleagues has been a major inspiration for the ensemble. Thus, Artemis Quartet has toured with notable musicians such as Sabine Meyer, Elisabeth Leonskaja, Juliane Banse and Jörg Widmann. Various recordings document the artistic cooperation with several partners, for example the piano quintets by Schuhmann and Brahms with Leif Ove Andsnes, the Schubert quintet with Truls Mørk or Arnold Schönberg’s ’Verklärte Nacht’ with Thomas Kakuska and Valentin Erben from Alban Berg Quartet. -

September 2013 for the Last Few Years There Has Been an Artist, Whose

September 2013 For the last few years there has been an artist, whose recordings regularly receive the highest ratings in FONOFORUM: Jerome Rose is his name, student of Rudolf Serkin, and one of the most important American pianists. On August 12th, he will celebrate his 75th Birthday – one more reason to present him. Mario-Felix Vogt met the artist in Paris. If one wants to describe Jerome Roses artistic personality, one should start with his Liszt- recordings. These works have the unfortunate fate of being rarely performed well in technical and musical aspects. Those musicians that have only mediocre pianistic skills lack the right tools, individualistic virtuosos lack text understanding and discipline and Competition pianists, who unspool his etudes often soulless like sowing machines, lack sensibility. Amongst the few pianists that can master Liszt’s manual demands and approach them with sense of structure and without sentimentality, are Svjatoslav Richter, Clifford Curzon – and Jerome Rose. His literally thundering recording of the piano piece “Orage” from the “Annees de pelerinage”, Suisse, shows that there is a true virtuoso within him. He plays it more powerful and brilliantly than his famous colleagues Daniel Barenboim and Alfred Brendel. Also his Transcendental Etudes are masterful: the etude “Feux folltes”, much feared for its eminent difficulty, flickers under his hands and is full of lightness. Yet, the exceptional about his playing is not his virtuosity – Russian key-acrobats like Lazar Berman and Boris Berezowsky know how to present these etudes even a tad more brilliantly and precicely – but the demeanor in which he approaches Liszt. -

January 20, 2018

January 20, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “It is utterly false and cruelly arbitrary to put all the play and learning into childhood, all the work into middle age, and all the regrets into old age.” — Margaret Mead Start Buy CD Stock Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Barcode Time online Number Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Chopin Etude in A minor, Op. 25 No. 4 Leif Ove Andsnes Virgin 91501 075679150127 00:04 Buy Now! Handel Music for the Royal Fireworks Concert des Nations/Savall Astree 9920 3298490099209 Hewitt/National Arts Centre 00:28 Buy Now! Mozart Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. 491 Hyperion 68049 034571280493 Orchestra/Lintu 01:00 Buy Now! Donizetti Ballet Music ~ Dom Sebastien Philharmonia/de Almeida Philips 422 844 028942284425 01:23 Buy Now! Griffes Poem for Flute and Orchestra Goff/Seattle Symphony/Schwarz Delos 3099 013491309927 Eastern Music Festival 01:35 Buy Now! Debussy La Mer (The Sea) Orchestra/Schwarz 02:00 Buy Now! Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 3 in D Gewandhaus Orchestra/Masur Philips 412 724 028941272423 02:09 Buy Now! Schubert Piano Sonata No. 18 in G, D. 894 "Fantasy" Alain Planès Harmonia Mundi 901697 794881503421 02:50 Buy Now! Bach, W.F. Flute Duet No. 1 in E minor Aurèle & Christiane Nicolet Denon 7287 N/A 02:59 Buy Now! Smetana The Moldau ~ Ma Vlast (My Fatherland) London Symphony/Dorati Mercury 462 953 028946295328 Orchestra of the Toulouse 03:14 Buy Now! Chausson Viviane, Symphonic Poem Op. 5 EMI 47894 5099974789429 Capitole/Plasson Wallfisch/London 03:28 Buy Now! Kabalevsky Cello Concerto No.