An Alternative Approach to the Problem of Midterm Demands for Contract Renegotiation in the National Football League: the Incentive-Based Contract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

WEEK 12 San Fran.Qxd

THE DOPE SHEET OFFICIAL PUBLICITY, GREEN BAY PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL CLUB VOL. V; NO. 17 GREEN BAY, NOV. 18, 2003 11th GAME PACKERS CAPTURE TEAM RUSHING LEAD: The NFL’s best teams, since Sept. 27, 1992 Packers last weekend swiped from Baltimore the title of league’s No. 1 rushing offense (166.5 yards per game). Brett Favre made his first start at quarterback — and first of a league-record 200 in consecutive fashion — Sept. 27, 1992, vs. Pittsburgh. The NFL’s top X Green Bay hasn’t finished a season leading the NFL in teams since that day: rushing since 1964 (150.4). The team hasn’t finished in the Top 5 since 1967, when they won the Ice Bowl. And, Team W L T Pct Super Bowls Playoff App. the Packers haven’t ranked in the Top 10 since they San Francisco 120 63 0 .656 1 9 Green Bay 120 63 0 .656 2 8 were seventh in 1972. Pittsburgh 109 73 1 .598 1 8 X The Packers have paced the NFL in rushing three other Miami 110 74 0 .598 0 8 times: 1946, when future Hall of Famer Tony Canadeo Denver 109 74 0 .596 2 5 shined in a deep backfield, and 1961-62, when Vince Kansas City 109 74 0 .596 0 5 Minnesota 107 76 0 .585 0 8 Lombardi’s feared Green Bay Sweep dominated the Hou./Ten. 105 78 0 .574 1 5 game and led the Packers to consecutive world champi- Dallas 102 81 0 .557 3 7 onships. -

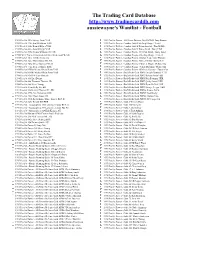

Pro Set Football Wantlist.Pdf

The Trading Card Database http://www.tradingcarddb.com aussiewayne's Wantlist - Football 1989 Pro Set 193c Stacey Toran VAR 1993 Pro Set Power - All-Power Defense Gold APD25 Tony Bennett 1989 Pro Set 478c Jim McMahon VAR 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Gold 2 Sterling Sharpe / Terrell 1989 Pro Set 480c Earnest Byner VAR 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Gold 4 Deion Sanders / Tim McKye 1989 Pro Set 483c Gerald Riggs VAR 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Gold 5 Bruce Smith / Darryl Tall 1989 Pro Set 535a Gizmo Williams RC, ER 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Prisms 1 Emmitt Smith / Barry Sand 1990 FACT Pro Set Cincinnati 338 Eric Dickerson PB, UE 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Prisms 2 Sterling Sharpe / Terrell 1990 Pro Set 161c Art Shell CO, CO 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Prisms 3 Junior Seau / Gary Plumme 1990 Pro Set 343c Chris Hinton PB, VA 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Prisms 5 Bruce Smith / Darryl Tall 1990 Pro Set 723a Oliver Barnett PSP, R 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Prisms 6 Warren Moon / Webster Sla 1990 Pro Set 772a Dexter Manley ERR 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Prisms 7 Chris Doleman / Henry Tho 1990 Pro Set NNOa Michael Dean Perry VAR 1993 Pro Set Power - Combos Prisms 10 Marco Coleman / Bryan Cox 1990 Pro Set NNOb Michael Dean Perry VAR 1993 Pro Set Power - Draft Picks Gold PDP1 Lincoln Kennedy UER 1990 Pro Set NNO William Roberts 1993 Pro Set Power - Draft Picks Gold PDP3 Robert Smith UER 1990 Pro Set 338 Lud Denny 1993 Pro Set Power - Draft Picks Gold PDP5 Dan Footman UER 1990 Pro Set 444 Thurman Thomas 3D 1993 Pro Set Power - Draft Picks Gold PDP7 -

Test Your Trivia Here

EATS & TREATS: September 2011 A GUIDE TO FOOD & FUN HOW MANY AGGIE TEAMS WON NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS IN 2010? NAME 5 TEXAS A&M ATHLETES WHAT IS THE OLDEST BUSINESS WHO NOW HAVE PRO SPORTS CAREERS ESTABLISHMENT IN COLLEGE STATION? TEST YOUR B RAZ OS VALLEY TRIVIA HERE September 2011 INSITE 1 2 INSITE September 2011 20 CONTENTS 5 MAKINGHISTORY Headed to the White House New exhibit shows what it takes to become President by Tessa K. Moore 7 LIFESTYLE Wanted: Texas Hospitality Families can share much with Aggies far from home by Tessa K. Moore 9 COMMUNITYOUTREACH A Legacy of Love Bubba Moore Memorial Group keeps the giving spirit alive by Megan Roiz INSITE Magazine is published monthly by Insite 11 GETINVOLVED Printing & Graphic Services, 123 E. Wm. J. Bryan Pkwy., Everyone Needs a Buddy Bryan, Texas 77803. (979) Annual walk raises more than just funds 823-5567 www.insitegroup. by Caroline Ward com Volume 28, Number 5. Publisher/Editor: Angelique Gammon; Account Executive: 12 ARTSSPOTLIGHT Myron King; Graphic Wanted: Dramatis Personae Designers: Alida Bedard; Karen Green. Editorial Or, How to get your Glee on around the Brazos Valley Interns: Tessa K. Moore, by Caroline Ward Megan Roiz, Caroline Ward; INSITE Magazine is a division of The Insite Group, LP. 15 DAYTRIP Reproduction of any part Visit Houston without written permission Find the metro spots that only locals know of the publisher is prohibited. Insite Printing & Graphic Services Managing Partners: 19 MUSICSCENE Kyle DeWitt, Angelique Beyond Price Gammon, Greg Gammon. Chamber concerts always world class, always free General Manager: Carl Dixon; Pre-Press Manager: Mari by Paul Parish Brown; Office Manager: Wendy Seward; Sales & Customer Service: Molly 20 QUIZTIME Barton; Candi Burling; Janice Feeling Trivial? Hellman; Manda Jackson; Test your Brazos Valley Trivia IQ Marie Lindley; Barbara by Tessa K. -

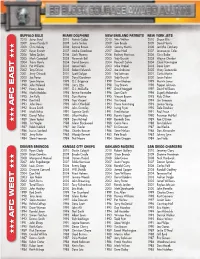

Afc East Afc West Afc East Afc

BUFFALO BILLS MIAMI DOLPHINS NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS NEW YORK JETS 2010 Jairus Byrd 2010 Patrick Cobbs 2010 Wes Welker 2010 Shaun Ellis 2009 James Hardy III 2009 Justin Smiley 2009 Tom Brady 2009 David Harris 2008 Chris Kelsay 2008 Ronnie Brown 2008 Sammy Morris 2008 Jerricho Cotchery 2007 Kevin Everett 2007 Andre Goodman 2007 Steve Neal 2007 Laveranues Coles 2006 Takeo Spikes 2006 Zach Thomas 2006 Rodney Harrison 2006 Chris Baker HHH 2005 Mark Campbell 2005 Yeremiah Bell 2005 Tedy Bruschi 2005 Wayne Chrebet 2004 Travis Henry 2004 David Bowens 2004 Rosevelt Colvin 2004 Chad Pennington 2003 Pat Williams 2003 Jamie Nails 2003 Mike Vrabel 2003 Dave Szott 2002 Tony Driver 2002 Robert Edwards 2002 Joe Andruzzi 2002 Vinny Testaverde 2001 Jerry Ostroski 2001 Scott Galyon 2001 Ted Johnson 2001 Curtis Martin 2000 Joe Panos 2000 Daryl Gardener 2000 Tedy Bruschi 2000 Jason Fabini 1999 Sean Moran 1999 O.J. Brigance 1999 Drew Bledsoe 1999 Marvin Jones 1998 John Holecek 1998 Larry Izzo 1998 Troy Brown 1998 Pepper Johnson 1997 Henry Jones 1997 O.J. McDuffie 1997 David Meggett 1997 David Williams 1996 Mark Maddox 1996 Bernie Parmalee 1996 Sam Gash 1996 Siupeli Malamala 1995 Jim Kelly 1995 Dan Marino 1995 Vincent Brown 1995 Kyle Clifton 1994 Kent Hull 1994 Troy Vincent 1994 Tim Goad 1994 Jim Sweeney AFC EAST 1993 John Davis 1993 John Offerdahl 1993 Bruce Armstrong 1993 Lonnie Young 1992 Bruce Smith 1992 John Grimsley 1992 Irving Fryar 1992 Dale Dawkins 1991 Mark Kelso 1991 Sammie Smith 1991 Fred Marion 1991 Paul Frase 1990 Darryl Talley 1990 Liffort Hobley -

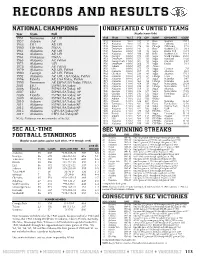

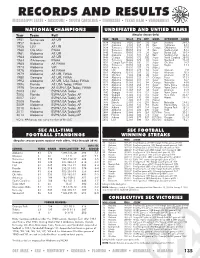

Records and Results

RECORDS AND RESULTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS UNDEFEATED & UNTIED TEAMS Year Team Poll (Regular Season Only) 1951 Tennessee AP, UPI YEAR TEAM W-L-T PTS OPP BOWL OPPONENT SCORE 1957 Auburn AP 1934 Alabama 9-0-0 287 32 Rose Stanford 29-13 1958 LSU AP, UPI 1937 Alabama 9-0-0 225 20 Rose California 0-13 1938 Tennessee 10-0-0 276 16 Orange Oklahoma 17-0 1960 Ole Miss FWAA 1939 Tennessee 10-0-0 212 0 Rose Southern Cal 0-14 1961 Alabama AP, UPI 1940 Tennessee 10-0-0 319 26 Sugar Boston Coll. 13-19 1964 Alabama AP, UPI 1945 Alabama 9-0-0 396 66 Rose Southern Cal 34-14 1946 Georgia 10-0-0 372 100 Sugar North Carolina 20-10 1964 #Arkansas FWAA 1951 Tennessee 10-0-0 373 88 Sugar Maryland 13-28 1965 Alabama AP, FWAA 1952 Georgia Tech 11-0-0 301 52 Sugar Ole Miss 24-7 1973 Alabama UPI 1956 Tennessee 10-0-0 268 75 Sugar Baylor 7-13 1978 Alabama AP, FWAA 1957 Auburn 10-0-0 207 28 (None) 1958 LSU 10-0-0 275 53 Sugar Clemson 7-0 1979 Alabama AP, UPI, FWAA 1961 Alabama 10-0-0 287 22 Sugar Arkansas 10-3 1980 Georgia AP, UPI, FWAA 1962 Ole Miss 9-0-0 230 40 Sugar Arkansas 17-13 1992 Alabama AP, UPI, USA Today, FWAA 1964 Alabama 10-0-0 223 67 Orange Texas 17-21 1996 Florida AP, USA Today, FWAA 1966 Alabama 10-0-0 267 37 Sugar Nebraska 34-7 1971 Alabama 11-0-0 362 84 Orange Nebraska 6-38 1998 Tenneseee AP, ESPN/USA Today, FWAA 1973 Alabama 11-0-0 454 89 Sugar Notre Dame 23-24 2003 LSU ESPN/USA Today 1974 Alabama 11-0-0 318 83 Orange Notre Dame 11-13 2006 Florida ESPN/USA Today, AP 1979 Alabama 11-0-0 359 58 Sugar Arkansas 24-9 1980 Georgia 11-0-0 316 127 Sugar Notre -

UF Relaxes Measles Policy for Fear of Losing Students Rather Than Risk Closing UP, Ad- Dents, up Infir May Director Boyd Bleak in August, by Sept

the indep-nden fItrid Students recount Soviet experience.13 Spurrier: 'There's no excuse' for UF's 27-3 Not 0111,0y as9twd wh Ihe Unrv. *y o Flo do PvbIhypM by Cmp., Comm .n.t.on. Irto ofGame. o victory..24 VOLUME 84, NUMBER 20 MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 24. 1990 Lombardi looks for alternative to NCAA penalty By SKAMON BENN Lombardi said Sunday he Is look- Both Lombardi and UP football compete tn a b owl game. Asking for the stronger penalty Alligator Staff Writer ing for a "reasonable alternative" coach Steve Spurrier said they One alternat ve is to request a would show the NCAA that UP is to the NCAA Committee on agree the penalty was too stiff be- harsherpenalty forthe football pro- willing to be punished (or its UP President John Lombardi Infractions'decision handed down cause it punishes the innocent foot. gram, such as a reduction of schol- wrongdoings, [ombardi said said he will announce Tuesday Thursday. The decision capped a ball players who are trying to win arships during the next two years, "it isn't reasonable that the com- whether the school will appeal an two-year investigation that un- their first Southeastern Confer- lombardi said. If UF takes that mittee will give us a lighter pun- NCAA ruling barring UF's football earthed violations committed by ence championship. According to route, the foot all team could win team from playing in a bowl game the football and men's basketball a 2-year-old SEC rule, the team is the SEC title and play in a bowl see NCAA. -

Week 12 Football Release.Qxp

SEC FOOTBALL 2009 Week 12 • Nov. 21 SECsports.com Southeastern Conference Media Relations SECSportsMedia.com • CollegePressBox.com EASTERN DIVISION LASTEST RANKINGS SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Home Away Neutral 2008 vs. Div. Top 25 Streak AP USA-T Harris BCS *Florida 8-0 1.000 221 96 10-0 1.000 339 105 5-0 4-0 1-0 9-1 5-0 1-0 W 10 1 1 1 1 Georgia 4-3 .571 207 218 6-4 .600 275 259 4-1 2-2 0-1 8-2 2-2 1-3 W 2 rv rv South Carolina 3-5 .375 144 195 6-5 .545 227 228 5-1 1-4 0-0 7-4 2-3 1-3 L 3 Kentucky 2-4 .333 122 165 6-4 .600 268 217 3-3 2-1 1-0 6-4 2-1 0-3 W 2 Tennessee 2-4 .333 138 135 5-5 .500 306 212 5-2 0-3 0-0 3-7 1-2 1-2 L 1 Vanderbilt 0-7 .000 55 160 2-9 .182 180 249 1-5 1-4 0-0 6-5 0-4 0-5 L 7 WESTERN DIVISION LASTEST RANKINGS SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Home Away Neutral 2008 vs. Div. Top 25 Streak AP USA-T Harris BCS *Alabama 7-0 1.000 182 64 10-0 1.000 309 109 6-0 3-0 1-0 10-0 4-0 4-0 W 10 2 3 3 2 LSU 4-2 .667 122 95 8-2 .800 250 137 5-1 3-1 0-0 7-3 2-1 1-2 W 1 10 10 10 8 Ole Miss 3-3 .500 128 112 7-3 .700 311 159 5-1 2-2 0-0 6-4 1-2 0-1 W 2 rv rv rv Auburn 3-4 .429 179 193 7-4 .636 374 297 6-1 1-3 0-0 5-6 3-1 1-1 L 1 rv rv rv Arkansas 2-4 .333 162 179 6-4 .600 376 255 5-1 0-3 1-0 4-6 1-2 1-4 W 3 Mississippi State 2-4 .333 118 166 4-6 .400 245 252 1-5 3-1 0-0 3-7 0-3 0-5 L 1 NOTES: 2008 - Record after same number of games in 2008 / vs. -

Super Bowl Xlvii

SUPER BOWL XLVII n emotionally-charged and perceived the run of losses to be Baltimore’s late-season Athrilling six weeks kicked demise, but the Ravens felt otherwise. As each wintry off the Baltimore Ravens’ 2012 week passed, the team’s resilient chemistry never faded, campaign. Despite playing their nor did its genuine belief that the best was yet to come. first four games in an 18-day span, the Ravens produced a 5-1 record, On Wild Card weekend, before a sellout M&T Bank Stadium marking the best start ever under crowd that celebrated and saluted Ray Lewis in his final home John Harbaugh. Highlighted by a game, Baltimore pummeled the Colts, 24-9, kick-starting an season-opening victory on Monday incredible playoff run. Holding Indy without a touchdown, the Night Football against division foe Ravens’ defense was led by Lewis, who returned to action for the first time since tearing his triceps in Week 6. Cincinnati and an exhilarating, last-second triumph over AFC rival “I think we’re all appreciative, grateful for the opportunity to New England, the Ravens immediately demonstrated the be here and to witness this historic moment in sports,” head type of heart and resolve that would allow them to conquer coach John Harbaugh said after the win. “And, it wasn’t just anything in an NFL season. about one guy [Lewis]. Nobody understands it more than Climbing to 9-2, Baltimore tied (2006) the then-best record the one guy we’re talking about. It was about a team. It was about a city, a fan base, a great sport, about a great career.” to begin a season in franchise history. -

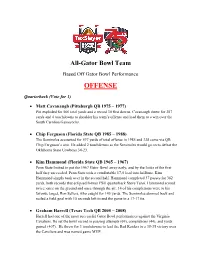

All-Gator Bowl Team Based Off Gator Bowl Performance OFFENSE

All-Gator Bowl Team Based Off Gator Bowl Performance OFFENSE Quarterback (Vote for 1) Matt Cavanaugh (Pittsburgh QB 1975 – 1977) Pitt exploded for 566 total yards and a record 30 first downs. Cavanaugh threw for 387 yards and 4 touchdowns to shoulder his team’s offense and lead them to a win over the South Carolina Gamecocks. Chip Ferguson (Florida State QB 1985 – 1988) The Seminoles accounted for 597 yards of total offense in 1985 and 338 came via QB Chip Ferguson’s arm. He added 2 touchdowns as the Seminoles would go on to defeat the Oklahoma State Cowboys 34-23. Kim Hammond (Florida State QB 1965 – 1967) Penn State looked to put the 1967 Gator Bowl away early, and by the looks of the first half they succeeded. Penn State took a comfortable 17-0 lead into halftime. Kim Hammond simply took over in the second half. Hammond completed 37 passes for 362 yards, both records that eclipsed former FSU quarterback Steve Tensi. Hammond scored twice; once on the ground and once through the air. 14 of his completions were to his favorite target, Ron Sellers, who caught for 145 yards. The Seminoles stormed back and nailed a field goal with 15 seconds left to end the game in a 17-17 tie. Graham Harrell (Texas Tech QB 2005 – 2008) Harrell had one of the most successful Gator Bowl performances against the Virginia Cavaliers. He set the bowl record in passing attempts (69), completions (44), and yards gained (407). He threw for 3 touchdowns to lead the Red Raiders to a 38-35 victory over the Cavaliers and was named game MVP. -

SEC Record Book

RECORDS AND RESULTS MISSISSIPPI STATE • MISSOURI • SOUTH CAROLINA • TENNESSEE • TEXAS A&M • VANDERBILT NATIONAL CHAMPIONS UNDEFEATED AND UNTIED TEAMS Year Team Poll (Regular Season Only) 1951 Tennessee AP, UPI YEAR TEAM W-L-T PTS OPP BOWL OPPONENT SCORE 1957 Auburn AP 1934 Alabama 9-0-0 287 32 Rose Stanford 29-13 1937 Alabama 9-0-0 225 20 Rose California 0-13 1958 LSU AP, UPI 1938 Tennessee 10-0-0 276 16 Orange Oklahoma 17-0 1960 Ole Miss FWAA 1939 Tennessee 10-0-0 212 0 Rose Southern Cal 0-14 1940 Tennessee 10-0-0 319 26 Sugar Boston Coll. 13-19 1961 Alabama AP, UPI 1945 Alabama 9-0-0 396 66 Rose Southern Cal 34-14 1964 Alabama AP, UPI 1946 Georgia 10-0-0 372 100 Sugar North Carolina 20-10 1964 #Arkansas FWAA 1951 Tennessee 10-0-0 373 88 Sugar Maryland 13-28 1952 Georgia Tech 11-0-0 301 52 Sugar Ole Miss 24-7 1965 Alabama AP, FWAA 1956 Tennessee 10-0-0 268 75 Sugar Baylor 7-13 1973 Alabama UPI 1957 Auburn 10-0-0 207 28 (None) 1978 Alabama AP, FWAA 1958 LSU 10-0-0 275 53 Sugar Clemson 7-0 1961 Alabama 10-0-0 287 22 Sugar Arkansas 10-3 1979 Alabama AP, UPI, FWAA 1962 Ole Miss 9-0-0 230 40 Sugar Arkansas 17-13 1980 Georgia AP, UPI, FWAA 1964 Alabama 10-0-0 223 67 Orange Texas 17-21 1966 Alabama 10-0-0 267 37 Sugar Nebraska 34-7 1992 Alabama AP, UPI, USA Today, FWAA 1971 Alabama 11-0-0 362 84 Orange Nebraska 6-38 1996 Florida AP, USA Today, FWAA 1973 Alabama 11-0-0 454 89 Sugar Notre Dame 23-24 1998 Tenneseee AP, ESPN/USA Today, FWAA 1974 Alabama 11-0-0 318 83 Orange Notre Dame 11-13 1979 Alabama 11-0-0 359 58 Sugar Arkansas 24-9 2003 LSU -

Oakland Raiders San Francisco 49Ers

SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS OAKLAND RAIDERS NO NAME POS HT WT AGE EXP COLLEGE NO NAME POS HT WT AGE EXP COLLEGE NO NAME POS 3 C.J. Beathard QB 6-2 215 24 2 Iowa 2 AJ McCarron QB 6-3 215 28 4 Alabama NO NAME POS 91 ...... Armstead, Arik ..................DL 4 Nick Mullens QB 6-1 210 23 1 Southern Mississippi 4 Derek Carr QB 6-3 215 27 5 Fresno State 88 ...... Ateman, Marcell ...............WR 3 ...... Beathard, C.J. .................. QB 5 Bradley Pinion P 6-5 240 24 4 Clemson 5 Johnny Townsend P 6-1 210 23 R Florida 95 ...... Brown, Fadol .....................DE 98 ...... Blair III, Ronald ..................DL 9 Robbie Gould K 6-0 190 35 14 Penn State 8 Daniel Carlson K 6-5 213 23 R Auburn 12 ...... Bryant, Martavis ..............WR 17 ...... Bolden Jr., Victor ..............WR 11 Marquise Goodwin WR 5-9 180 27 6 Texas 10 Seth Roberts WR 6-2 195 27 4 West Alabama 53 ...... Cabinda, Jason .................LB 84 ...... Bourne, Kendrick..............WR 13 Richie James Jr. WR 5-9 185 23 R Middle Tennessee State 12 Martavis Bryant WR 6-4 210 26 4 Clemson 91 ...... Calhoun, Shilique ..............LB 22 ...... Breida, Matt ......................RB 14 Tom Savage QB 6-4 230 28 5 Pittsburgh 17 Dwayne Harris WR/RS 5-11 206 31 8 East Carolina 8 ...... Carlson, Daniel ...................K 99 ...... Buckner, DeForest .............DL 15 Pierre Garçon WR 6-0 211 32 11 Mount Union 19 Brandon LaFell WR 6-3 210 31 9 LSU 4 ...... Carr, Derek ....................... QB 88 ...... Celek, Garrett ...................