Beverley Brook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Summary Report

Report by Rocket Science for The Barnes Fund This report draws on a wide range of data and on benefitted enormously from their input. Second, the experiences of a diverse sample of local we are grateful to 41 representatives from local residents to tell the story of need within our organisations who came together in focus groups community. The Barnes Fund concluded in late to discuss need in Barnes; to a number of others 2019 that we would like to commission such a who shared their views separately; to the 12 report in 2020, our 50th anniversary year, both to residents who took on the challenge of being inform our own grant making programme and as a trained as peer researchers; and to the 110 community resource. In the event the work was residents who agreed to be interviewed by them. carried out at a time when experience of Covid-19 The report could not have been written without and lockdown had sharpened many residents’ sense their willingness to provide frank feedback, of both ‘community’ and ‘need’ and there was much thoughts and ideas. And finally, we are grateful to that was being learned. At the same time, we have Rocket Science, who were chosen by the Steering been keen to take a longer-term perspective – both Group based on their expertise and relevant backwards in terms of understanding what pre- experience to carry out the research on our behalf, existing data tells us about ourselves and forwards who rose to the challenge of doing everything in terms of understanding hopes, concerns and remotely (online or via the phone) and who have expectations beyond the immediate health listened to, questioned, and directed us all before emergency. -

HA16 Rivers and Streams London's Rivers and Streams Resource

HA16 Rivers and Streams Definition All free-flowing watercourses above the tidal limit London’s rivers and streams resource The total length of watercourses (not including those with a tidal influence) are provided in table 1a and 1b. These figures are based on catchment areas and do not include all watercourses or small watercourses such as drainage ditches. Table 1a: Catchment area and length of fresh water rivers and streams in SE London Watercourse name Length (km) Catchment area (km2) Hogsmill 9.9 73 Surbiton stream 6.0 Bonesgate stream 5.0 Horton stream 5.3 Greens lane stream 1.8 Ewel court stream 2.7 Hogsmill stream 0.5 Beverley Brook 14.3 64 Kingsmere stream 3.1 Penponds overflow 1.3 Queensmere stream 2.4 Keswick avenue ditch 1.2 Cannizaro park stream 1.7 Coombe Brook 1 Pyl Brook 5.3 East Pyl Brook 3.9 old pyl ditch 0.7 Merton ditch culvert 4.3 Grand drive ditch 0.5 Wandle 26.7 202 Wimbledon park stream 1.6 Railway ditch 1.1 Summerstown ditch 2.2 Graveney/ Norbury brook 9.5 Figgs marsh ditch 3.6 Bunces ditch 1.2 Pickle ditch 0.9 Morden Hall loop 2.5 Beddington corner branch 0.7 Beddington effluent ditch 1.6 Oily ditch 3.9 Cemetery ditch 2.8 Therapia ditch 0.9 Micham road new culvert 2.1 Station farm ditch 0.7 Ravenbourne 17.4 180 Quaggy (kyd Brook) 5.6 Quaggy hither green 1 Grove park ditch 0.5 Milk street ditch 0.3 Ravensbourne honor oak 1.9 Pool river 5.1 Chaffinch Brook 4.4 Spring Brook 1.6 The Beck 7.8 St James stream 2.8 Nursery stream 3.3 Konstamm ditch 0.4 River Cray 12.6 45 River Shuttle 6.4 Wincham Stream 5.6 Marsh Dykes -

Walks Programme: July to September 2021

LONDON STROLLERS WALKS PROGRAMME: JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2021 NOTES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING COVID-19: Following discussions with Ramblers’ Central Office, it has been confirmed that as organized ‘outdoor physical activity events’, Ramblers’ group walks are exempt from other restrictions on social gatherings. This means that group walks in London can continue to go ahead. Each walk is required to meet certain requirements, including maintenance of a register for Test and Trace purposes, and completion of risk assessments. There is no longer a formal upper limit on numbers for walks; however, since Walk Leaders are still expected to enforce social distancing, and given the difficulties of doing this with large numbers, we are continuing to use a compulsory booking system to limit numbers for the time being. Ramblers’ Central Office has published guidance for those wishing to join group walks. Please be sure to read this carefully before going on a walk. It is available on the main Ramblers’ website at www.ramblers.org.uk. The advice may be summarised as: - face masks must be carried and used, for travel to and from a walk on public transport, and in case of an unexpected incident; - appropriate social distancing must be maintained at all times, especially at stiles or gates; - you should consider bringing your own supply of hand sanitiser, and - don’t share food, drink or equipment with others. Some other important points are as follows: 1. BOOKING YOUR PLACE ON A WALK If you would like to join one of the walks listed below, please book a place by following the instructions given below. -

FOIA-EIR Decision Notice Template

Reference: FER0829694 Freedom of Information Act 2000(FOIA) Environmental Information Regulations 2004 (EIR) Decision notice Date: 12 May 2020 Public Authority: Wimbledon and Putney Commons Conservators Address: Manor Cottage Windmill Road Wimbledon Common London SW19 5NR Decision (including any steps ordered) 1. The complainant has requested information regarding an agreement to exchange land between Wimbledon and Putney Commons Conservators (WPCC) and Royal Wimbledon Golf Club (RWGC). 2. WPCC refused to comply with the request on the basis that it was manifestly unreasonable, citing regulation 12(4)(b). 3. The Commissioner’s decision is that WPCC is entitled to rely on regulation 12(4)(b) to refuse to comply with the request and that in the circumstances of this case, the public interest lies in maintaining the exception. 4. The Commissioner does not require the public authority to take any steps. Background 5. Wimbledon and Putney Commons is a charity managed by WPCC. It was established under The Wimbledon and Putney Common Act 1871 (the 1871 Act). The Commons comprise some 1140 acres across Wimbledon Common, Putney Heath and Putney Lower Common. 1 Reference: FER0829694 6. Under the 1871 Act, it is the duty of the Conservators (five elected and three appointed) to keep the Commons open, unenclosed, unbuilt on and their natural aspect preserved. 7. Wimbledon and Putney Commons is largely funded by a levy on local residents which is administered through the Council Tax collected by three councils, namely Wandsworth, Merton and Kingston. 8. The Commissioner understands that arrangements between WPCC and RWGC date back to as early as 1954. -

Royal Borough of Kingston: Views Study P R a Views Vs

pra Views Vs ese iews ae ee ise r ei siere as Ver il pra Views r il pra Views as e lill e rieria a piall ae e r re reeprs rai as less a i All reaii iews ieiie as Vs epass a rae ales r eaple e Viewi ai a e Ver i a a esiae lasapes i wi i alls e iew isel a l ra as ei Vale as ere a e a er isal erars r e wsape iew is liie ie araer ils ese iews are Ver il r il pra i is sill awlee a ese iews are ipra 298 Ver i Ver i i • Appraisal View 58 • Appraisal View 60 • Appraisal View 61 • Appraisal View 70 • Appraisal View 103 • Appraisal View 104 • Appraisal View 105 • Appraisal View 61 • Appraisal View 146 • Appraisal View 148 • Appraisal View 156 • Appraisal View 157 • Appraisal View 158 • Appraisal View 189 299 APPRAISAL DATA SHEET FOR HIGH LEVEL ASSESSMENT OF VIEWS VIEWPOINT REF NO: 58 APPRAISED BY: AM / SR DATE: 06.04.2017 VIEWPOINT LOCATION: E:517634, N:169291 Publically Accessible? Yes Standing in Barge Walk looking almost directly opposite southern grounds of All Saints Church Viewing Location 1 Nature of Access Footpath 2 Is the view static or part of a series of views Static 3 Is the location designated Hampton Wick Conservation Area 4 Character Area and Key Characteristics Hampton Wick Conservation Area No 18, Sub Area 4.2 – The Riverside, south of Kingston Bridge Along River Thames Riverscape. Kingston Bridge Boatyard, Barge Walk – tranquil area outside the grounds of Hampton Court Park The breadth of the river allows unique views into the heart of Kingston. -

The London Rivers Action Plan

The london rivers action plan A tool to help restore rivers for people and nature January 2009 www.therrc.co.uk/lrap.php acknowledgements 1 Steering Group Joanna Heisse, Environment Agency Jan Hewlett, Greater London Authority Liane Jarman,WWF-UK Renata Kowalik, London Wildlife Trust Jenny Mant,The River Restoration Centre Peter Massini, Natural England Robert Oates,Thames Rivers Restoration Trust Kevin Reid, Greater London Authority Sarah Scott, Environment Agency Dave Webb, Environment Agency Support We would also like to thank the following for their support and contributions to the programme: • The Underwood Trust for their support to the Thames Rivers Restoration Trust • Valerie Selby (Wandsworth Borough Council) • Ian Tomes (Environment Agency) • HSBC's support of the WWF Thames programme through the global HSBC Climate Partnership • Thames21 • Rob and Rhoda Burns/Drawing Attention for design and graphics work Photo acknowledgements We are very grateful for the use of photographs throughout this document which are annotated as follows: 1 Environment Agency 2 The River Restoration Centre 3 Andy Pepper (ATPEC Ltd) HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This booklet is to be used in conjunction with an interactive website administered by the The River Restoration Centre (www.therrc.co.uk/lrap.php).Whilst it provides an overview of the aspirations of a range of organisations including those mentioned above, the main value of this document is to use it as a tool to find out about river restoration opportunities so that they can be flagged up early in the planning process.The website provides a forum for keeping such information up to date. -

Wandsworth Council Parks and Open Spaces Byelaws

Official Wandsworth Borough Council BYELAWS FOR PLEASURE GROUNDS, PUBLIC WALKS AND OPEN SPACES ARRANGEMENT OF BYELAWS PART 1 GENERAL 1. General interpretation 2. Application 3. Opening times PART 2 PROTECTION OF THE GROUND, ITS WILDLIFE AND THE PUBLIC 4. Protection of structures and plants 5. Unauthorised erection of structures 6. Climbing 7. Grazing 8. Protection of wildlife 9. Gates 10. Camping 11. Fires 12. Missiles 13. Interference with life-saving equipment PART 3 HORSES, CYCLES AND VEHICLES 14. Interpretation of Part 3 15. Horses 16. Cycling 17. Motor vehicles 18. Overnight parking Official PART 4 PLAY AREAS, GAMES AND SPORTS 19. Interpretation of Part 4 20. Children’s play areas 21. Children’s play apparatus 22. Skateboarding, etc 23. Ball games 24. Ball games - rules 25. Cricket 26. Archery 27. Field sports 28. Golf PART 5 WATERWAYS 29. Interpretation of Part 5 30. Bathing 31. Ice skating 32. Model boats 33. Boats 34. Fishing 35. Pollution 36. Blocking of watercourses PART 6 MODEL AIRCRAFT 37. Interpretation of Part 6 38. Model aircraft PART 7 OTHER REGULATED ACTIVITIES 39. Provision of services 40. Excessive noise 41. Public shows and performances 42. Aircraft, hang-gliders and hot air balloons 43. Kites 44. Metal detectors 2 Official PART 8 MISCELLANEOUS 45. Obstruction 46. Savings 47. Removal of offenders 48. Penalty 49. Revocation SCHEDULE 1 - Grounds to which byelaws apply generally SCHEDULE 2 - Grounds referred to in certain byelaws SCHEDULE 3 - Rules for playing ball games in designated areas 3 Official Byelaws made under section 164 of the Public Health Act 1875/sections 12 and 15 of the Open Spaces Act 1906 by Wandsworth Borough Council with respect to its pleasure grounds, public walks and open spaces. -

Upper Tideway (PDF)

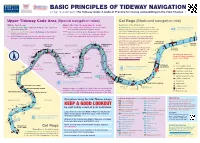

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

U P P E R R I C H M O N D R O

UPPER RICHMOND ROAD CARLTON HOUSE VISION 02-11 PURE 12-25 REFINED 26-31 ELEGANT 32-39 TIMELESS 40-55 SPACE 56-83 01 CARLTON HOUSE – FOREWORD OUR VISION FOR CARLTON HOUSE WAS FOR A NEW KIND OF LANDMARK IN PUTNEY. IT’S A CONTEMPORARY RESIDENCE THAT EMBRACES THE PLEASURES OF A PEACEFUL NEIGHBOURHOOD AND THE JOYS OF ONE OF THE MOST EXCITING CITIES IN THE WORLD. WELCOME TO PUTNEY. WELCOME TO CARLTON HOUSE. NICK HUTCHINGS MANAGING DIRECTOR, COMMERCIAL 03 CARLTON HOUSE – THE VISION The vision behind Carlton House was to create a new gateway to Putney, a landmark designed to stand apart but in tune with its surroundings. The result is a handsome modern residence in a prime spot on Upper Richmond Road, minutes from East Putney Underground and a short walk from the River Thames. Designed by award-winning architects Assael, the striking façade is a statement of arrival, while the stepped shape echoes the rise and fall of the neighbouring buildings. There’s a concierge with mezzanine residents’ lounge, landscaped roof garden and 73 apartments and penthouses, with elegant interiors that evoke traditional British style. While trends come and go, Carlton House is set to be a timeless addition to the neighbourhood. Carlton House UPPER RICHMOND ROAD Image courtesy of Assael 05 CARLTON HOUSE – LOCATION N . London Stadium London Zoo . VICTORIA PARK . Kings Place REGENT’S PARK . The British Library SHOREDITCH . The British Museum . Royal Opera House CITY OF LONDON . WHITE CITY Marble Arch . St Paul’s Cathedral . Somerset House MAYFAIR . Tower of London . Westfield London . HYDE PARK Southbank Centre . -

4. Roehampton Gate Walk

Short Walks in Richmond Park 4. Roehampton Gate Roehampton Gate Garden - 50 m - Turn left away from * * the gates on the path Ash tree Distance and terrain: 2,100m (1¼ miles). Easy walk with slight gradients and some uneven ground. We recommend you * towards the car park. * Wych elm (P1) This is one of a series of self-guided, short, nature walks from Park gates. take a tree ID book/app More willows on * Beverley Brook (P4) For longer self-guided walks, try our Walks with Remarkable Trees: www.frp.org.uk/tree-walks/ Cross the road and pass between two when walking this route. small copses on the other side. Walk to * some fenced trees and then fork right towards three small trees with cones on. The walk starts with a large ash tree just beyond the small Roehampton Gate garden. P1 * Ashes can carry male or female flowers or occasionally both – this one is female. * * Fenced veteran oaks * Cross the road, Three alder trees (P2) A little further on is a wych elm (P1) with toothed slightly asymmetrical leaves, which turn right and go * Turn left towards the brook and then has withstood the threat of Dutch Elm Disease. back to the start. * walk to the road bridge 350m away. Fantastic crack willows along Beverley Brook Over the road is an example of some fencing around Blasted oak (see text) * Turn right when you get to veteran oak trees. The fencing (partly funded by the road, cross the bridge Friends of Richmond Park) protects the public from and (counting from the right) Many of Keep right over the take the second main path the danger of falling branches and protects the tree the English oaks in bridge at the bottom up the slope. -

Outdoor Learning Providers in the Borough

Providers of Outdoor Learning in Richmond Environmental, Friends of Parks and Residents Groups Environment Trust Website: www.environmenttrust.co.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8891 5455 Contact: Stephen James Events are advertised on http://www.environmenttrust.co.uk/whats-on Friends of Barnes Common Website: www.barnescommon.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 07855 548 404 Contact: Sharon Morgan Events are advertised on www.barnescommon.org.uk/learning Friends of Bushy and Home Parks Website: www.fbhp.org.uk Email: [email protected] Events are advertised on www.fbhp.org.uk/walksandtalks Green Corridor Land based horticultural qualifications for young people aged 14-35. Website: www.greencorridor.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 01403 713 567 Contact: Julie Docking Updated March 2016 Friends of the River Crane Environment (FORCE) Website: www.force.org.uk Email: [email protected] For walks and talks, community learning, and outdoor learning for schools in sites in the lower Crane Valley see http://e-voice.org.uk/force/calendar/view Friends of Carlisle Park Website: http://e-voice.org.uk/friendsofcarlislepark/ Ham United Group Website: www.hamunitedgroup.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8940 2941 Contact: Penny Frost River Thames Boat Project Educational, therapeutic and recreational cruises and activities on the River Thames. Website: www.thamesboatproject.org Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8940 3509 Contact: Pippa Thames Explorer Trust Website: www.thames-explorer.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8742 0057 Contact: Lorraine Conterio or Simon Clarke Summer playscheme - www.thames-explorer.org.uk/families/summer-playscheme Foreshore walks - www.thames-explorer.org.uk/foreshore-walks/ YMCA London South West Website: www.ymcalsw.org Contact: Myke Catterall Updated March 2016 Thames Young Mariners Thames Young Mariners in Ham offer outdoor learning opportunities for schools, youth groups, families and adults all year round including day and residential visits. -

1000 Years of Barnes History V5

Over 1000 years of Barnes History Timeline from 925 to 2015 925 Barnes, formerly part of the Manor of Mortlake owned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, is given by King Athelstan to the Dean and Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral. 1085 Grain sufficient to make 3 weeks supply of bread and beer for the Cathedral’s live-in Canons must be sent from Barnes to St Paul’s annually. Commuted to money payment late 15th Century. 1086 Domesday Book records Barnes valued for taxation at £7 p.a. Estimated population 50-60. 1100 - 1150 Original St Mary‘s Parish Church built at this time (Archaeological Survey 1978/9). 1181 Ralph, Dean of St Paul’s, visits Barnes, Wednesday 28th Jan to assess the value of the church and manor. The priest has 10 acres of Glebe Land and a tenth of the hay crop. 1215 Richard de Northampton, Priest at the Parish Church. Archbishop Stephen Langton said to have re-consecrated the newly enlarged church on his return journey from Runnymede after the sealing of Magna Carta. 1222 An assessment of the Manor of Barnes by Robert the Dean. Villagers must work 3 days a week on the demesne (aka the Barn Elms estate) and give eggs, chickens and grain as in 1085 in return for strips of land in the open fields. Estimated population 120. 1388 Living of Barnes becomes a Rectory. Rector John Lynn entitled to Great Tithes (10% of all produce) and right of fishing in Barnes Pond. 1415 William de Millebourne dies at Milbourne House.