Chapter One Defining Hypocrisy and Insincerity Introduction I Intend In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the Internet on His State- Freshly Recovered from His Nervous Breakdown, Lemonhead Owned Computer

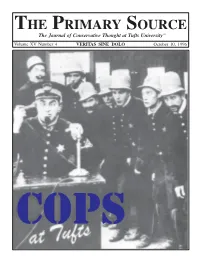

THE PRIMARY SOURCE The Journal of Conservative Thought at Tufts University SM Volume XV Number 4 VERITAS SINE DOLO October 10, 1996 COPS Hey, Adolf, I I though you had heard Prof. Trout to be a real social- is gonna get ten- ist to get tenure ured after all. here. Frustrated with commie professors? Join THE PRIMARY SOURCE Weekly Meeting: Wednesdays at 8:00 PM Zamparelli Room (112 Campus Cen- ter) or call Jessica at 627-7576 or email us: [email protected] 2 THE PRIMARY SOURCE, OCTOBER 10, 1996 THE PRIMARY SOURCE The Journal of Conservative Thought at Tufts UniversitySM vol. XV no. 4 october 10, 1996 CONTENTS Departments FROM THE EDITOR 4 POSTCARDS 5 COMMENTARY 6 FORTNIGHT IN REVIEW 8 NOTABLE AND QUOTABLE 24 TUFTS'S PARKING SCAM BRIGHT LIGHTS, BIG CITY COLIN DELANEY KEITH LEVENBERG Taking a serious look at this issue's main topic, Mr. Welcome to Dystopia, population 250 million. Big Delaney examines the reasons why TUPD unnecessar- Brother makes a bad city planner, just look around ily ticketed so many students' cars recently. 10 your home town. 15 TAKING THE INITIATIVE Special Section JESSICA S CHUPAK Revisiting the California Civil Rights Initiative and its abolition of mandated preferential treatment. 17 TUPD UNPLUGGED REMEDIAL COMMON SENSE ANANDA G UPTA On the Beat Our nation's public school system is more concerned with indoctrination that education. 19 The Cops' Happy Page SOMETHING FISHY JEFF BETTENCOURT ✫ We smuggled some of those snazzy Watch out! The Domestic Names Committee of the US pamphlets out of TUPD's stationhouse Board of Geographical Names is coming. -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

Political Science; *Polits; Secondary 7Ducation; Social Studies; Sociology; United States History 7PENTIF:7 PS *Irish Ami.Ricans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 129 690 SO 009 470 AUTHOF Krug, Mark M. -"TTL7 White Ethnic Groups and American Politics, Student Book. The Lavinia and Charles P. Schwartz Citizenship Project. INST7TUTI711 Chicago Univ., Ill. Graduate School of Education. 1DUB DATE 72 NOTE 99p.; For related documents, see SO 009 469-474 EDFS PF:CE MF-$0.83 HC-$4.67 Plus Postage. DESCFIPTOFS *Citizenship; Ethnic Grouping; *Ethnic Groups; Ethnic Studies; *Ethnocentrism; Italian Americans; Jews; Polish Americans; Political Science; *Polits; Secondary 7ducation; Social Studies; Sociology; United States History 7PENTIF:7 PS *Irish Ami.ricans ABSIPACT This student book, one in a series of civic education materials, focuses on white ethnic groups and how they influence the operation of the American political system. The ethnicgroups which are investigated include Poles, Irish, Italians, and Jews. An ethnic person is defined as anyone who decides to identify with and live among those who share the same immigrant memories and values. Ethnic origin, ethnic loyalties, and ethnic considerations playan important role in the political process of the United States. A separate chapter focuses on each of the four minority groups and its role in the process of American politics. Jews, labeled as the shaken liberals, have historically been staunch supporters of the liberal tradition as a unified voter block, but apparent conservative trends are showing as a reaction to radical liberalism and its support of the Arab nations. The Irish built and dominated political organizations, known as machines, in several cities and their predominance in city politics continues today. Italians'were rather slow in getting into politics, but in general Italiansare politically conservative, strong American patriots, disunited due to internal identity conflicts, and assimilating rapidly into U.S. -

Chapter One: Postwar Resentment and the Invention of Middle America 10

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Timothy Melley, Director ________________________________________ C. Barry Chabot, Reader ________________________________________ Whitney Womack Smith, Reader ________________________________________ Marguerite S. Shaffer, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT TALES FROM THE SILENT MAJORITY: CONSERVATIVE POPULISM AND THE INVENTION OF MIDDLE AMERICA by Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff In this dissertation I show how the conservative movement lured the white working class out of the Democratic New Deal Coalition and into the Republican Majority. I argue that this political transformation was accomplished in part by what I call the "invention" of Middle America. Using such cultural representations as mainstream print media, literature, and film, conservatives successfully exploited what came to be known as the Social Issue and constructed "Liberalism" as effeminate, impractical, and elitist. Chapter One charts the rise of conservative populism and Middle America against the backdrop of 1960s social upheaval. I stress the importance of backlash and resentment to Richard Nixon's ascendancy to the Presidency, describe strategies employed by the conservative movement to win majority status for the GOP, and explore the conflict between this goal and the will to ideological purity. In Chapter Two I read Rabbit Redux as John Updike's attempt to model the racial education of a conservative Middle American, Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom, in "teach-in" scenes that reflect the conflict between the social conservative and Eastern Liberal within the author's psyche. I conclude that this conflict undermines the project and, despite laudable intentions, Updike perpetuates caricatures of the Left and hastens Middle America's rejection of Liberalism. -

Download File

Tow Center for Digital Journalism CONSERVATIVE A Tow/Knight Report NEWSWORK A Report on the Values and Practices of Online Journalists on the Right Anthony Nadler, A.J. Bauer, and Magda Konieczna Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 7 Boundaries and Tensions Within the Online Conservative News Field 15 Training, Standards, and Practices 41 Columbia Journalism School Conservative Newswork 3 Executive Summary Through much of the 20th century, the U.S. news diet was dominated by journalism outlets that professed to operate according to principles of objectivity and nonpartisan balance. Today, news outlets that openly proclaim a political perspective — conservative, progressive, centrist, or otherwise — are more central to American life than at any time since the first journalism schools opened their doors. Conservative audiences, in particular, express far less trust in mainstream news media than do their liberal counterparts. These divides have contributed to concerns of a “post-truth” age and fanned fears that members of opposing parties no longer agree on basic facts, let alone how to report and interpret the news of the day in a credible fashion. Renewed popularity and commercial viability of openly partisan media in the United States can be traced back to the rise of conservative talk radio in the late 1980s, but the expansion of partisan news outlets has accelerated most rapidly online. This expansion has coincided with debates within many digital newsrooms. Should the ideals journalists adopted in the 20th century be preserved in a digital news landscape? Or must today’s news workers forge new relationships with their publics and find alternatives to traditional notions of journalistic objectivity, fairness, and balance? Despite the centrality of these questions to digital newsrooms, little research on “innovation in journalism” or the “future of news” has explicitly addressed how digital journalists and editors in partisan news organizations are rethinking norms. -

SDS's Failure to Realign the Largest Political Coalition in the 20Th Century

NEW DEAL TO NEW MAJORITY: SDS’S FAILURE TO REALIGN THE LARGEST POLITICAL COALITION IN THE 20TH CENTURY Michael T. Hale A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2015 Committee: Clayton Rosati, Advisor Francisco Cabanillas Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Oliver Boyd-Barret Bill Mullen ii ABSTRACT Clayton Rosati, Advisor Many historical accounts of the failure of the New Left and the ascendency of the New Right blame either the former’s militancy and violence for its lack of success—particularly after 1968—or the latter’s natural majority among essentially conservative American voters. Additionally, most scholarship on the 1960s fails to see the New Right as a social movement. In the struggles over how we understand the 1960s, this narrative, and the memoirs of New Leftists which continue that framework, miss a much more important intellectual and cultural legacy that helps explain the movement’s internal weakness. Rather than blame “evil militants” or a fixed conservative climate that encircled the New Left with both sanctioned and unsanctioned violence and brutality––like the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) counter intelligence program COINTELPRO that provide the conditions for a unstoppable tidal wave “with the election of Richard M. Nixon in 1968 and reached its crescendo in the Moral Majority, the New Right, the Reagan administration, and neo-conservatism” (Breines “Whose New Left” 528)––the key to this legacy and its afterlives, I will argue, is the implicit (and explicit) essentialism bound to narratives of the “unwinnability” of especially the white working class. -

ALAN WOLFE Curriculum Vitae – Updated May 2016

ALAN WOLFE Curriculum Vitae – updated May 2016 CURRENT POSITION: 1999-2016: Director of the Boisi Center for Religion and American Public Life and Professor of Political Science, Boston College. PREVIOUS POSITIONS 1993-1999: University Professor and Professor of Sociology and Political Science, Boston University. 1991-1993: Dean of the Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science and Michael E. Gellert Professor of Sociology and Political Science, New School for Social Research. 1979-89: Associate Professor and Professor of Sociology, Queens College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. 1989: Adjunct Professor, Department of Sociology, Columbia University. 1987-88: Visiting Professor, University of Aarhus, Denmark. Fall 1982: Visiting Scholar, Center for European Studies, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1978-80: Visiting Scholar, Institute for the Study of Social Change, University of California, Berkeley, California. 1977-79: Visiting Associate Professor of Sociology, University of California, Santa Cruz, California. 1970-78: Assistant and Associate Professor of Sociology, City University of New York, Richmond College. 1968-70: Assistant Professor of Political Science, College at Old Westbury, State University of New York. 1966-68: Assistant Professor of Political Science, Rutgers, The State University, Douglass College. PUBLICATIONS: BOOKS: At Home in Exile: Why Diaspora is Good for the Jews. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014. Paperback edition: Boston: Beacon Press, 2015. Political Evil: What It Is and How To Combat It, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011. Paperback edition: New York: Vintage Books, 2012. Religion and Democracy in the United States: Danger or Opportunity? (co-editor with Ira Katznelson) Alan Wolfe Page 2 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. -

Te US and Northeast Asia in a Turbulent Time

2016 IGE/KITA Global Trade Forum Te US and Northeast Asia in a Turbulent Time Gerald L. Curtis Gerald L. Curtis Gerald L. Curtis Donald Trump Hillary Clinto Bernie Sanders Trump phenomenon limousine liberal Goldman Sachs Barack Obama internationalist Elizabeth Warren social liberals Tea Party Ted Cruz John Kasich TPP lame duck gold standard Jeb Bush Q A Q A John Kerry Q A engagement strategy ASEAN engagement) AIIB World Bank IMF ADB credibility Q A Q A Q A ill Clinton Q A Q A Gerald Curtis Gerald -

Race and Relative Deprivation in the Urban United States

REEVE D. VANNEMAN AND THOMAS F. PETTIGREW Race and Relative Deprivation in the Urban United States INTRODUCTION This study develops out of two separate literatures in social psychology- one concerned with the subjective aspects of social stratification, the other with the correlates of racial attitudes. The first of these areas has a rich history in social science, while the second is of recent vintage. We shall sketch out briefly these two literatures, followed by the presentation of our research findings relevant to both. Subjective Aspects of Social Stratification It has long been recognized in sociology and social anthropology as well as in social psychology that the objective features of a society’s social stratifica- tion system only grossly predict individual attitudes and behaviour. Deviant cases are so numerous that popular names arise to describe them: the Tory worker, the genteel poor, the limousine liberal. Early theorists took up the issue. Cooley discussed ’selective affinity’ to groups outside of one’s immediate environment; William James argued that our potential ’social self’ is developed and strengthened by thoughts of remote groups and individuals who function as normative points of reference (Hyman and Singer, 1968). But it was not until the 1940s that modern nomenclature and theory was established. Hyman (1942) advanced the term reference group to account for his interview and experimental data on how his subjects employed status comparisons in the process of self-appraisal. An individual, he argues, typically ’refers’ his behaviour and attitudes to a variety of reference groups to which he may or may not belong. The concept soon found wide favour throughout social psychology, for, as Newcomb points out (1951), it focuses upon the central problem of the discipline: the relationship of the individual to society. -

The Claim of U.S. Exceptionalism Within a Context of Race, Gender and Class Inequality

Journal of Law and Judicial System Volume 2, Issue 3, 2019, PP 7-17 ISSN 2637-5893 (Online) The Claim of U.S. Exceptionalism within a Context of Race, Gender and Class Inequality Julian B. Roebuck, Komanduri S. Murty* Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Fort Valley State University, USA *Corresponding Author: Komanduri S. Murty, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Fort Valley State University, USA, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT American exceptionalism has gained considerable attention among scholars and political leaders alike. Some scholars pointed out that the presence and extent of U.S. exceptionalism is that procedural political democracy has been spelled out in the U.S. legal system; that is, universal participation; political equality; majority rule; representative democracy; and, governmental responses to public opinion—all under the rule of law. However, there is no U.S. official definition of, or call for any kind of, or control of economic equality; though, in fact much economic inequality has always existed in the U.S.; and moreover, is now increasing at a more rapid rate than in the past. And yet, the U.S. politicians, especially those running for the presidency, find it necessary to consider American exceptionalism as an article of faith that must be accepted and promulgated. This article attempts to shed some light on America’s so-called exceptionalism and the need of an equalized economic society. Keywords: Civil Rights; Liberalism; Manifest Destiny; human rights; Great Depression; cultural knowledge; political parties; economic inequality; grid locking. INTRODUCTION SOME BRIEF HISTORICAL NOTES ON American exceptionalism is currently the AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM subject of many books, scholarly articles, and The idea that the Unites States has been singled popular publications. -

Thesis Template

“The Metropolitan Moment: Municipal Boundaries, Segregation, and Civil Rights Possibilities in the American North” by Michael Gray Savage A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Michael Gray Savage 2018 “The Metropolitan Moment: Municipal Boundaries, Segregation, and Civil Rights Possibilities in the American North” Michael Gray Savage Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2018 Abstract Exploring battles over school desegregation in metropolitan Boston, Detroit, and Philadelphia in the 1960s and 1970s, “The Metropolitan Moment” examines how black and white city dwellers at odds over integration within the city pursued – and sometimes allied over – efforts that crossed municipal lines to incorporate the suburbs in desegregation remedies. Though possessing divergent motivations, such as the white tactical aim of ensuring white majorities in all area schools by enlarging the desegregation area and the black desire for improved educational opportunities, both groups sought access to white suburban schools and at times acted together in court in an attempt to implement metropolitan desegregation. The search for such solutions opened a “metropolitan moment” across the urban North in the late 1960s and early 1970s when proposed regional remedies offered real possibilities of heading off white flight, fostering interracial coalitions, and substantively combatting segregation. Though this moment was foreclosed by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1974 decision in Milliken v. Bradley – a case prompted in part by just such a surprising urban black-white alliance in Detroit – its legacies, including suburban anti-busing movements that helped fuel the rise of the New Right and the transformation of the Democratic Party, and the larger retreat from metropolitan solutions to metropolitan dilemmas of race, schooling, services, and inequality, echo down to today. -

Construction of the Racist Republican

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Spring 5-10-2014 Construction of the Racist Republican Barbara M. Lane Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Lane, Barbara M., "Construction of the Racist Republican." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/81 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTION OF THE RACIST REPUBLICAN by BARBARA LANE Under the Direction of John McMillian Abstract Minorities have gained more civil rights with the cooperation of both major political parties in the United States, yet the actions of the Republican Party are often conflated with racism. This is partially the result of clashes in ideological visions, which explain the different political positions of partisans. However, during his 1980 run for the White House, a concerted effort was made to tie Ronald Reagan to racism, as he was accused of pandering to white Southerners. Therefore, this thesis also focuses on “Southern strategies” used by both the Republican and Democratic parties to exploit race, which have spilled into the new millennium. INDEX WORDS: Racist Republican, Southern Strategy,