Charter Management Organizations 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Local District Homeless Education Liaisons

2009 – 2010 Michigan Local District McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Liaisons School District & Code Liaison Name & Position Phone & Email Academic and Career Education Academy Beth Balgenorth 989‐631‐5202 x229 56903 School Counselor [email protected] Academic Transitional Academy Laura McDowell 810 364 8990 74908 Homeless Liaison/Coord [email protected] Acad. for Business & Technology Elem. Rachel Williams 313‐581‐2223 82921 Homeless Liaison [email protected] Acad. for Business & Tech., High School Gloria Liveoak 313‐382‐3422 82921 Para Educator [email protected] Academy of Detroit‐West Laticia Swain 313‐272‐8333 82909 Counsler [email protected] Academy of Flint Verdell Duncan 810‐789‐9484 25908 Principal [email protected] Academy of Inkster Raymond Alvarado 734‐641‐1312 82961 Principal [email protected] Academy of Lathrup Village Yanisse Rhodes 248‐569‐0089 63904 Title I Representative [email protected] Academy of Oak Park‐Marlow Campus (Elem) Rashid Fai Sal 248‐547‐2323 63902 Dean of Students/School Social Worker [email protected] Acad. of Oak Park, Mendota Campus (HS) Millicynt Bradford 248‐586‐9358 63902 Counselor [email protected] Academy of Oak Park‐Whitcomb Campus (Middle School) L. Swain 63902 [email protected] Academy of Southfield Susan Raines 248‐557‐6121 63903 Title I Facilitator [email protected] Academy of Warren Evelyn Carter 586‐552‐8010 50911 School Social Worker [email protected] Academy of Waterford -

Wayne County Regional Educational Service Agency

Wayne County Regional Educational Service Agency Plan for the Delivery of Special Education Programs and Services February 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • Demographics of Wayne County 1-2 • Wayne RESA Overview • Regional Framework A. Procedures to Provide Special Education Services 2-10 • Special Education Opportunities Required Under Law • Obligations of Wayne RESA and the LEAs/PSAs • Special Education Representatives (figure 1) B. Communicating the Availability of Special Education Programs 11 • Activities and Outreach Methods • Procedures for Identifying Potential Special Education Populations C. Diagnostic and Related Services 12-13 • Overview of Services • Contracts for Purchased Services • Diagnostic and Related Services (figure 2) D. Special Education Programs for Students with Disabilities 14 • Continuum of Programs and Services • Placement in Center Program for the Hearing Impaired • Administrators Responsible for Special Education • LEA/PSA Special Education Programs (figure 3, figure 4) 15-17 • Alternative Special Education Programs 18 E. Transportation for Special Education Programs and Services 19 • Basic Requirements • Additional Responsibility F. Act 18 Millage Funds 19 • Method of Distribution G. Wayne County Parent Advisory Committee 19-21 • Roles and Responsibilities • Appointment Process • Administrative and Fiscal Support H. Additional Plan Content 21 • Qualifications of Paraprofessional Personnel • Professional Personnel Assigned to Special Education • Confidentiality Assurance Statement • Expanded Age Range -

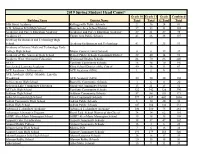

2019 Spring Student Head Count*

2019 Spring Student Head Count* Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade Combined Building Name District Name Total Total 12 Total Total 54th Street Academy Kelloggsville Public Schools 21 36 24 81 A.D. Johnston Jr/Sr High School Bessemer Area School District 39 33 31 103 Academic and Career Education Academy Academic and Career Education Academy 27 21 27 75 Academy 21 Center Line Public Schools 43 26 38 107 Academy for Business and Technology High School Academy for Business and Technology 41 17 35 93 Academy of Science Math and Technology Early College High School Mason County Central Schools 0 0 39 39 Academy of The Americas High School Detroit Public Schools Community District 39 40 14 93 Academy West Alternative Education Westwood Heights Schools 84 70 86 240 ACCE Ypsilanti Community Schools 28 48 70 146 Accelerated Learning Academy Flint, School District of the City of 40 16 11 67 ACE Academy - Jefferson site ACE Academy (SDA) 1 2 0 3 ACE Academy (SDA) -Glendale, Lincoln, Woodward ACE Academy (SDA) 50 50 30 130 Achievement High School Roseville Community Schools 3 6 11 20 Ackerson Lake Community Education Napoleon Community Schools 15 21 15 51 ACTech High School Ypsilanti Community Schools 122 142 126 390 Addison High School Addison Community Schools 57 54 60 171 Adlai Stevenson High School Utica Community Schools 597 637 602 1836 Adrian Community High School Adrian Public Schools 6 10 20 36 Adrian High School Adrian Public Schools 187 184 180 551 Advanced Technology Academy Advanced Technology Academy 106 100 75 281 Advantage Alternative Program -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Calculation of Solar Motion for Localities in the USA

American Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2021; 9(1): 1-7 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajaa doi: 10.11648/j.ajaa.20210901.11 ISSN: 2376-4678 (Print); ISSN: 2376-4686 (Online) Calculation of Solar Motion for Localities in the USA Keith John Treschman Science/Astronomy, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia Email address: To cite this article: Keith John Treschman. Calculation of Solar Motion for Localities in the USA. American Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Vol. 9, No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-7. doi: 10.11648/j.ajaa.20210901.11 Received: December 17, 2020; Accepted: December 31, 2020; Published: January 12, 2021 Abstract: Even though the longest day occurs on the June solstice everywhere in the Northern Hemisphere, this is NOT the day of earliest sunrise and latest sunset. Similarly, the shortest day at the December solstice in not the day of latest sunrise and earliest sunset. An analysis combines the vertical change of the position of the Sun due to the tilt of Earth’s axis with the horizontal change which depends on the two factors of an elliptical orbit and the axial tilt. The result is an analemma which shows the position of the noon Sun in the sky. This position is changed into a time at the meridian before or after noon, and this is referred to as the equation of time. Next, a way of determining the time between a rising Sun and its passage across the meridian (equivalent to the meridian to the setting Sun) is shown for a particular latitude. This is then applied to calculate how many days before or after the solstices does the earliest and latest sunrise as well as the latest and earliest sunset occur. -

2008 Annual Report.Pdf

Connecting Youth to a Brighter Future 2008 Annual Report Letter from the President Board of Directors Somebody recently asked me what our organization’s main accomplishments were in the area of youth development. I replied with two words: “Making Chairman, Hon. Freddie Burton, Jr., connections.” Wayne County Probate Court When asked to expand I immediately talked about our accomplishments to date and our plans for the future. Vice Chair, Herman Gray, M.D., As an agency, The Youth Connection helps to make Children’s Hospital connections – we connect youth and parents to after- school programs, and students to summer internship and career development opportunities. We connect Secretary, Trisha Johnston, businesses that want to make a difference in a young HP person’s life to opportunities that allow them to help. Most importantly, we make connection through partnerships. The partnerships we Treasurer, Paul VanTiem, have formed with organizations like the Detroit Fire Department and the City of Alterra Detroit have strengthened our mission to make metropolitan Detroit the best place to raise a family. N. Charles Anderson, Through events like our annual After-School Fair and our summer internship programs Detroit Urban League we are trying to make sure that our children can see that their future is full of possibilities and that there are people who care about them. James Barren, Connections. Partnerships. Possibilities. These words and actions will continue to Detroit Police Department guide us as we develop additional programs to help youth in the foster care system through a grant from the Detroit Workforce Development Department. Vernice Davis-Anthony, We are thankful for your help and support through our first 12 years and we look forward to continue our work on behalf of parents and children of Detroit. -

NCAA Bowl Eligibility Policies

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2019-20 Bowl Schedule ..................................................................................................................2-3 The Bowl Experience .......................................................................................................................4-5 The Football Bowl Association What is the FBA? ...............................................................................................................................6-7 Bowl Games: Where Everybody Wins .........................................................................8-9 The Regular Season Wins ...........................................................................................10-11 Communities Win .........................................................................................................12-13 The Fans Win ...................................................................................................................14-15 Institutions Win ..............................................................................................................16-17 Most Importantly: Student-Athletes Win .............................................................18-19 FBA Executive Director Wright Waters .......................................................................................20 FBA Executive Committee ..............................................................................................................21 NCAA Bowl Eligibility Policies .......................................................................................................22 -

Building Healthy Communities: Engaging Elementary Schools

Building Healthy Communities: Engaging Elementary Schools through Partnership Academy of International Studies Blair Elementary School Academy of Warren Borland Road Elementary Albion Elementary School Botsford Elementary School Alcott Elementary Bow Elementary/Middle Alexander Elementary School Brace-Lederle School All Saints Catholic School Brenda Scott Academy All Saints Catholic School Brookside Elementary School Allen Academy Brownell STEM Academy Allen Elementary School Buckley Community Elementary School Alonzo Bates Academy Byron Elementary School American International Academy CA Frost Environmental Science Academy Pk-5. Amerman Elementary School Campbell Elementary Anchor Elementary School Carleton Elementary School Andrews Elementary School Carney-Nadeau Elementary School Angell Elementary School Carver STEM Academy Ann Arbor Open School Cass Elementary Ann Arbor Trail Magnet School Central Elementary School Ann Visger Preparatory Academy Century Park Learning Center Ardmore Elementary Challenger Elementary Arts & Technology Academy of Pontiac Chandler Park Aspen Ridge School Charles H. Wright Academy of Arts and Science Atherton Elementary School Charles L Spain Elementary-Middle School Auburn Elementary Chormann Elementary School Avoca Elementary Christ the King Catholic School Baldwin Elementary Cleveland Elementary Bangor Central Elementary School Clinton Valley Elementary Bangor Lincoln Elementary School Cole Academy Bangor West Elementary School Coleman Elementary Barkell Elementary Columbia Elementary School Barth Elementary -

Shell-Less Opisthobranchs of Virginia and Maryland

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1978 Shell-less opisthobranchs of Virginia and Maryland Rosalie M. Vogel College of William and Mary - Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Vogel, Rosalie M., "Shell-less opisthobranchs of Virginia and Maryland" (1978). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539616894. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25773/v5-6gnb-fq17 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS Thii notarial was produced from a microfilm copy of tha original document. While the moit advanced technological meant to photograph end reproduce dm document have been uiad, the quality it heavily dependent upon tha quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of technique* it provided to help you understand marking* or pattern! which may appear on thii reproduction. 1. Tha sign or "target" for page* apparently lacking from tha document photographed i* "Missing Page I*}". If it wat possible to obtain the missing page(t) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent page*. This may have necessitated cutting thru an Image and duplicating adjacent page* to insure you complete continuity- 2. When an Image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it it an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Charter School Bond Issuance: a Complete History

Local Initiatives Support Corporation Charter School Bond Issuance: A Complete History June 2011 CHARTER SCHOOL BOND IssUANCE: A COMPLETE HISTORY Written By Elise Balboni Wendy Berry Charles Wolfson June 2011 Published By The Educational Facilities Financing Center of Local Initiatives Support Corporation www.lisc.org/effc This publication and related resources are available at http://www.lisc.org/effc/bondhistory LOCAL INITIATIVES SUPPORT CORPORATION EDUCATIONAL FACILITIES FINANCING CENTER Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) is dedicated to helping The Educational Facilities Financing Center (EFFC) at LISC supports community residents transform distressed neighborhoods into healthy and quality public charter schools in distressed neighborhoods. LISC founded sustainable communities of choice and opportunity — good places to work, the EFFC in 2003 to intensify its national effort in educational facilities do business and raise children. LISC mobilizes corporate, government and financing. The EFFC pools low-interest loan and grant funds and leverages philanthropic support to provide local community-based organizations with: them for investment in charter school facilities in order to create new or renovated school facilities for underserved children, families and ■■loans, grants and equity investments neighborhoods nationally. Since making its first charter school grant in ■■local, statewide and national policy support 1997, LISC has provided over $100 million in grants, loans and guarantees for approximately 140 schools across the country. The EFFC fosters long- ■■technical and management assistance term sustainability of the charter sector by identifying replicable financing mechanisms and sharing best practices and data through publications such LISC is a national organization with a community focus. Our program staff as the Landscape series and this report. -

OKLAHOMA State Board of Registration for Professional Engineers

OKLAHOMA State Board of Registration for Professional Engineers Twenty-Seventh Annual Report 1962 Copy of Registration Law and A Roster of Registered Professional Engineers Semco Color Press — Oklahoma Citv NAMES AND TERMS OF OFFICE OF FORMER BOARD MEMBERS OF THE STATE BOARD OF REGISTRATION FOR PROFESSIONAL ENGINEERS Geo. J. Stein, P.E., Miami 1935-1936 Boyd S. Myers, P.E., Houston Tex 1935-1937 J. F. Brooks, P.E., Norman 1935-1938 T. P. Clonts, P.E., Muskogee (Deceased) 1935-1939 W. C. Roads, P.E., Tulsa 1935-1940 O. C. Wemhaner, P.E., Miami (Deceased) 1936-1942 Philip S. Donnell, P.E., Sheepscott, Maine 1937-1942 W. H. Stueve, P.E., Oklahoma City (Deceased). 1938-1951 Guy B. Treat, P.E., Oklahoma City 1939-1951 Chas. D. Watson, P.E., Tulsa 1940-1945 R. V. James, P.E., Norman . 1942-1951 E. C. Baker, P.E., Stillwater (Deceased) 1942-1947 C. V. Millikan, P.E., Tulsa 1945-1951 J. S. Clark, P.E., Newkirk 1948-1953 F. Edgar Rice, P.E., Bartlesville 1951-1955 F. J. Meyer, P.E., Oklahoma City 1951-1957 H. E. Bailey, P.E., Oklahoma City 1956-1957 Jack H. Abernathy, P.E., Oklahoma City 1953-1958 Edward R. Stapley, P.E., Stillwater 1951-1959 Roy J. Thompson, P.E., Oklahoma City 1955-1960 Harris Bateman, P.E., Bartlesville 1957-1961 David E. Fields, P.E., Tulsa 1951-1956 and 1957-1962 DAVID B. BENHAM, P.E. WILLIAM J. FELL, P.E. Senior Partner Fell & Wheeler Benham Engineering Company Engineers and Affiliates Bachelor of Science 1941 B.S. -

School Corporation County POC Name POC Email 21St Century Charter School Lake Anthony Cherry ACE Preparatory Academy Marion Kris

School Corporation County POC Name POC Email 21st Century Charter School Lake Anthony Cherry [email protected] ACE Preparatory Academy Marion Kristen Walker [email protected] Adams Central Community Schools Adams Megan Workinger [email protected] Alexandria Community School Corporation Madison Scott Zent [email protected] Anderson Community School Corporation Madison Angie Vickery [email protected] Anderson Preparatory Academy Madison Jill Barker [email protected] Andrew J Brown Academy Marion Julia Conner-Fox [email protected] Argos Community Schools Marshall Kayla Montel [email protected] Aspire Charter Academy Lake Ms. Regina Puckett [email protected] Attica Consolidated School Corporation Fountain Dusty Goodwin [email protected] Avon Community School Corporation Hendricks Dr. Maryanne McMahon [email protected] Avondale Meadows Academy Marion Stephanie Mackenzie [email protected] Barr-Reeve Community Schools Daviess Travis G. Madison [email protected] Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation Bartholomew Larry Perkinson [email protected] Batesville Community School Corp Ripley Melissa Burton [email protected] Baugo Community Schools Elkhart James DuBois [email protected] Beech Grove City Schools Marion Mary Sibley-Story [email protected] Benton Community School Corporation Benton Gregg Hoover [email protected] Blackford County Schools Blackford Dr. James Trinkle [email protected] Bloomfield School District