No Foundations 12 ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers and Creative Advisors Selected for Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media contacts: March 23, 2016 Chalena Cadenas 310.360.1981 [email protected] Mauli Singh [email protected] Writers and Creative Advisors Selected for Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48 Lab Recognizes and Supports Six Emerging Independent Filmmakers from India Los Angeles, CA — Sundance Institute and Drishyam Films today announced the artists and creative advisors selected for the second Drishyam | Sundance Institute Screenwriters Lab in Udaipur, India April 48. The Lab supports emerging filmmakers in India, as part of the Institute’s sustained commitment to international artists, which in the last 25 years has included programs in Brazil, Mexico, Jordan, Turkey, Japan, Cuba, Israel and Central Europe. Now in its second year, the fourday Lab is a creative and strategic partnership between Drishyam Films and Sundance Institute, and gives independent screenwriters the opportunity to work intensively on their feature film scripts in an environment that encourages innovation and creative risktaking. The Lab is centered around oneonone story sessions with creative advisors. Screenwriting fellows engage in an artistically rigorous process that offers lessons in craft, a fresh perspective on their work and a platform to fully realize their material. Leading the Lab in India is Drishyam founder, Manish Mundra. He said, “A beautiful heritage city in my hometown of Rajasthan, Udaipur forms an ideal writers retreat, and is the perfect environment for a diverse group of emerging writers and renowned mentors to have a refreshing and productive exchange. Our goal is that the six selected Indian projects, after undergoing a comprehensive mentoring process, will quickly move from script to screen and make their mark globally. -

STATISTICAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 the 14Th LOK SABHA

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2004 TO THE 14th LOK SABHA VOLUME III (DETAILS FOR ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME III (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 6 2. Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies 7 - 1332 Election Commission of India, General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 7 . AC Arunachal Congress 8 . ADMK All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 9 . AGP Asom Gana Parishad 10 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 11 . AITC All India Trinamool Congress 12 . BJD Biju Janata Dal 13 . CPI(ML)(L) Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (Liberation) 14 . DMK Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 15 . FPM Federal Party of Manipur 16 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 17 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 18 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 19 . JKN Jammu & Kashmir National Conference 20 . JKNPP Jammu & Kashmir National Panthers Party 21 . JKPDP Jammu & Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party 22 . JMM Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 23 . KEC Kerala Congress 24 . KEC(M) Kerala Congress (M) 25 . MAG Maharashtrawadi Gomantak 26 . MDMK Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 27 . MNF Mizo National Front 28 . MPP Manipur People's Party 29 . MUL Muslim League Kerala State Committee 30 . -

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Integrated Report 2020 Index

INTEGRATED REPORT 2020 INDEX 4 28 70 92 320 PRESENTATION CORPORATE GOVERNANCE SECURITY METHODOLOGY SWORN STATEMENT 29 Policies and practices 71 Everyone’s commitment 93 Construction of the report 31 Governance structure 96 GRI content index 35 Ownership structure 102 Global Compact 5 38 Policies 103 External assurance 321 HIGHLIGHTS 74 104 Glossary CORPORATE STRUCTURE LATAM GROUP EMPLOYEES 42 75 Joint challenge OUR BUSINESS 78 Who makes up LATAM group 105 12 81 Team safety APPENDICES 322 LETTER FROM THE CEO 43 Industry context CREDITS 44 Financial results 47 Stock information 48 Risk management 83 50 Investment plan LATAM GROUP CUSTOMERS 179 14 FINANCIAL INFORMATION INT020 PROFILE 84 Connecting people This is a 86 More digital travel experience 180 Financial statements 2020 navigable PDF. 15 Who we are 51 270 Affiliates and subsidiaries Click on the 17 Value generation model SUSTAINABILITY 312 Rationale buttons. 18 Timeline 21 Fleet 52 Strategy and commitments 88 23 Passenger operation 57 Solidary Plane program LATAM GROUP SUPPLIERS 25 LATAM Cargo 62 Climate change 89 Partner network 27 Awards and recognition 67 Environmental management and eco-efficiency Presentation Highlights Letter from the CEO Profile Corporate governance Our business Sustainability Integrated Report 2020 3 Security Employees Customers Suppliers Methodology Appendices Financial information Credits translated at the exchange rate of each transaction date, • Unless the context otherwise requires, references to “TAM” although a monthly rate may also be used if exchange rates are to TAM S.A., and its consolidated affiliates, including do not vary widely. TAM Linhas Aereas S.A. (“TLA”), which operates under the name “LATAM Airlines Brazil”, Fidelidade Viagens e Turismo Conventions adopted Limited (“TAM Viagens”), and Transportes Aéreos Del * Unless the context otherwise requires, references to Mercosur S.A. -

Genocide in Gujarat the Sangh Parivar, Narendra Modi, and the Government of Gujarat

Genocide in Gujarat The Sangh Parivar, Narendra Modi, and the Government of Gujarat Coalition Against Genocide March 02, 2005 _______________________________ This report was compiled by Angana Chatterji, Associate Professor, Anthropology, California Institute of Integral Studies; Lise McKean, Deputy Director, Center for Impact Research, Chicago; and Abha Sur, Lecturer, Program in Women's Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; with the support of various members of the Coalition Against Genocide. We acknowledge the critical assistance provided by certain graduate students, who played a substantial role in shaping this report through research and writing. In writing this, we are indebted to the courage and painstaking work of various individuals, commissions, groups and organizations. Relevant records and documents are referenced, as necessary, in the text and in footnotes. Genocide in Gujarat The Sangh Parivar, Narendra Modi, and the Government of Gujarat Contents Gujarat: Narendra Modi and State Complicity in Genocide---------------------------------------------------3 * Under Narendra Modi’s leadership, between February 28 and March 02, 2002, more than 2,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed in Gujarat, aided and abetted by the state, following which 200,000 were internally displaced. * The National Human Rights Commission of India held that Narendra Modi, as the chief executive of the state of Gujarat, had complete command over the police and other law enforcement machinery, and is such responsible for the role of the Government of Gujarat in providing leadership and material support in the politically motivated attacks on minorities in Gujarat. * Former President of India, K. R. Narayanan, stated that there was a “conspiracy” between the Bharatiya Janata Party governments at the Centre and in the State of Gujarat behind the riots of 2002. -

VIVEKANANDA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION About

Policies & Perspectives VIVEKANANDA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION Pathetic Plight of India’s Opposition Ranks Rajesh Singh 30 May 2017 With the Government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi entering into its fourth year in office, various surveys conducted across the country have indicated the following: Modi remains immensely popular among the people; his leadership is considered decisive and firm; his Government is seen as pro-poor but not anti- industry; some of the regime’s actions, such as last year’s surgical strikes into Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and the de-monetisation decision, have received popular acclaim; the Government is seen as corruption-free; the economy is back on track even if adequate job-creation remains an issue. The surveys have also shown that, if general elections were to be held today or as scheduled in May 2019, the BJP and its allies under Modi’s leadership would be re-elected with a thumping majority. In short, after three years in office, the Government has the same high popular appeal as it did when it came to power. If this is not worrying enough for the opposition parties, there is more. Most respondents in the surveys believed that the Opposition had lost touch with the masses; it did not have a strong narrative to take on Prime Minister Modi and his Government; it lacked a strong leadership; it had lost credibility; it had thrown in the towel well before the grand contest was to happen. The more the opposition parties try to forge unity — as in the case of the presidential election — the more they are seen to be admitting to their incapacity of taking on the ruling dispensation on their own individual strength. -

The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

THE HINDU, THE MUSLIM, AND THE BORDER IN NATIONALIST SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA Vinay Lal University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There is but no question that we can speak about the emergence of the (usually Pakistani or Muslim) ‘terrorist’ figure in many Bollywood films, and likewise there is the indisputable fact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the political and public sphere. Indian cinema, however, may also be viewed in the backdrop of political developments in Pakistan, where the project of Islamicization can be dated to least the late 1970s and where the turn to a Wahhabi-inspired version of Islam is unmistakable. I argue that the recent history of Pa- kistan must be seen as instigated by a disavowal of the country’s Indic self, and similarly I suggest that scholarly and popular studies of the ‘representation’ of the Muslim in “Bol- lywood” rather too easily assume that such a figure is always the product of caricature and stereotyping. But the border between Pakistan and India, between the self and the other, and the Hindu and the Muslim is rather more porous than we have imagined, and I close with hints at what it means to both retain and subvert the border. Keywords: Border, Communalism, Indian cinema, Nationalism, Pakistan, Partition, Veer-Zaara Resumen 103 Así como el personaje del ‘terrorista’ (generalmente musulmán o paquistaní) está presente en muchos filmes de Bollywood, el nacionalismo hindú está tomando la iniciativa en la esfera política del país. Sin embargo el cine indio también puede hacerse eco de acontecimientos ocurridos en Paquistán, donde desde los años Setenta se ha manifestado un proceso de islamización de la sociedad, con una indudable impronta wahabí. -

Sustaining Employment and Wage Gains in Brazil

Sustaining Employment and Wage Gains in Brazil Wage and Sustaining Employment DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development Sustaining Employment and Wage Gains in Brazil A Skills and Jobs Agenda Joana Silva, Rita Almeida, and Victoria Strokova Sustaining Employment and Wage Gains in Brazil DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development Sustaining Employment and Wage Gains in Brazil A Skills and Jobs Agenda Joana Silva, Rita Almeida, and Victoria Strokova © 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 18 17 16 15 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

World Cinema Amsterd Am 2

WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM 2011 3 FOREWORD RAYMOND WALRAVENS 6 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM JURY AWARD 7 OPENING AND CLOSING CEREMONY / AWARDS 8 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION 18 INDIAN CINEMA: COOLLY TAKING ON HOLLYWOOD 20 THE INDIA STORY: WHY WE ARE POISED FOR TAKE-OFF 24 SOUL OF INDIA FEATURES 36 SOUL OF INDIA SHORTS 40 SPECIAL SCREENINGS (OUT OF COMPETITION) 47 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM OPEN AIR 54 PREVIEW, FILM ROUTES AND HET PAROOL FILM DAY 55 PARTIES AND DJS 56 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM ON TOUR 58 THANK YOU 62 INDEX FILMMAKERS A – Z 63 INDEX FILMS A – Z 64 SPONSORS AND PARTNERS WELCOME World Cinema Amsterdam 2011, which takes place WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION from 10 to 21 August, will present the best world The 2011 World Cinema Amsterdam competition cinema currently has to offer, with independently program features nine truly exceptional films, taking produced films from Latin America, Asia and Africa. us on a grandiose journey around the world with stops World Cinema Amsterdam is an initiative of in Iran, Kyrgyzstan, India, Congo, Columbia, Argentina independent art cinema Rialto, which has been (twice), Brazil and Turkey and presenting work by promoting the presentation of films and filmmakers established filmmakers as well as directorial debuts by from Africa, Asia and Latin America for many years. new, young talents. In 2006, Rialto started working towards the realization Award winners from renowned international festivals of a long-cherished dream: a self-organized festival such as Cannes and Berlin, but also other films that featuring the many pearls of world cinema. Argentine have captured our attention, will have their Dutch or cinema took center stage at the successful Nuevo Cine European premieres during the festival. -

View, See Phillipe C

BOARD OF EDITORS David Apter, David Baltimore, Daniel Bell, Guido Calabresi, Natalie Z. Davis, Wendy Doniger, Clifford Geertz, Stephen J. Greenblatt, Vartan Gregorian, Stanley Hoffmann, Gerald Holton, Donald Kennedy, Sally F. Moore, W. G. Runciman, Amartya K. Sen, Steven Weinberg STEPHEN R. GRAUBARD Editor of Dædalus PHYLLIS S. BENDELL Managing Editor SARAH M. SHOEMAKER Associate Editor MARK D. W. EDINGTON Consulting Editor MARY BRIDGET MCMULLEN Circulation Manager and Editorial Assistant Cover design by Michael Schubert, Director of Ruder-Finn Design Printed on recycled paper frontmatter sp00.p65 1 05/01/2000, 1:01 PM DÆDALUS JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Brazil: The Burden of the Past; The Promise of the Future Spring 2000 Issued as Volume 129, Number 2, of the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences frontmatter sp00.p65 2 05/01/2000, 1:01 PM Spring 2000, “Brazil: The Burden of the Past; The Promise of the Future” Issued as Volume 129, Number 2, of the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. ISBN 0-87724-021-3 © 2000 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Library of Congress Catalog Number 12-30299. Editorial Offices: Dædalus, Norton’s Woods, 136 Irving Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. Telephone: (617) 491-2600; Fax: (617) 576-5088; Email: [email protected] Dædalus (ISSN 0011-5266) is published quarterly by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. U.S. subscription rates: for individuals—$33, one year; $60.50, two years; $82.50, three years; for institutions—$49.50, one year; $82.50, two years; $110, three years. -

National Human Rights Commission Vs State of Gujarat

SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) OF 2003 (Against the Final Judgment and Order dated 27.6.2003 of the Additional Sessions Judge, Fast Track Court No.1, Vadodara, Gujarat passed in Sessions Case No.248 of 2002 APPEALED FROM) in the matter of NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION (PETITIONER) Versus STATE OF GUJARAT AND OTHERS (RESPONDENTS) with CRL.M.P.NO.______of 2003- Application For Exemption From Filing Certified Copy Of Impugned Judgment And Order; and CRL.M.P. NO.______of 2003 - Application For Ad-Interim Exparte Stay Directions; and CRL.M.P. NO. _______of 2003 - Application For Permission To File Special Leave Petiton Against The Judgment And Order Dated 27.6.2003 Of The Addl. Sessions Judge Directly In This Hon’ble Court; and CRL.M.P. NO. _______of 2003 - Application For Permission To Urge Additional Facts; and CRL.M.P. NO. _______of 2003 - Application For Exemption From Filing Official Translation IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION ADVOCATE FOR THE PETITIONER: S.Muralidhar This paper can be downloaded in PDF format from IELRC’s website at http://www.ielrc.org/content/c0302.pdf International Environmental Law Research Centre International Environment House Chemin de Balexert 7 & 9 1219 Châtelaine Geneva, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Table of Content SYNOPSIS AND LIST OF DATES 1 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. __ OF 2003 4 P R A Y E R 21 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO._______OF 2003 22 CERTIFICATE 22 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO._______OF 2003 23 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO.________OF 2003 24 PRAYER 25 SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO.________OF 2003 26 CRL.M.P. -

Kishore Booklet Copy

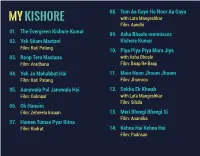

08. Tum Aa Gaye Ho Noor Aa Gaya with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Aandhi 01. The Evergreen Kishore Kumar 09. Asha Bhosle reminisces 02. Yeh Sham Mastani Kishore Kumar Film: Kati Patang 10. Piya Piya Piya Mora Jiya 03. Roop Tera Mastana with Asha Bhosle Film: Aradhana Film: Baap Re Baap 04. Yeh Jo Mohabbat Hai 11. Main Hoon Jhoom Jhoom Film: Kati Patang Film: Jhumroo 05. Aanewala Pal Janewala Hai 12. Dekha Ek Khwab Film: Golmaal with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Silsila 06. Oh Hansini Film: Zehreela Insaan 13. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si Film: Anamika 07. Hamen Tumse Pyar Kitna Film: Kudrat 14. Kehna Hai Kehna Hai Film: Padosan 2 3 15. Raat Kali Ek Khwab Mein 23. Mere Sapnon Ki Rani Film: Buddha Mil Gaya Film: Aradhana 16. Aate Jate Khoobsurat Awara 24. Dil Hai Mera Dil Film: Anurodh Film: Paraya Dhan 17. Khwab Ho Tum Ya Koi 25. Mere Dil Mein Aaj Kya Hai Film: Teen Devian Film: Daag 18. Aasman Ke Neeche 26. Ghum Hai Kisi Ke Pyar Mein with Lata Mangeshkar with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Jewel Thief Film: Raampur Ka Lakshman 19. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Hogi 27. Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Kuch Film: Mr. X In Bombay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Ghar 20. Teri Duniya Se Hoke Film: Pavitra Papi 28. Sama Hai Suhana Suhana Film: Ghar Ghar Ki Kahani 21. Kuchh To Log Kahenge Film: Amar Prem 29. O Mere Dil Ke Chain Film: Mere Jeevan Saathi 22. Rajesh Khanna talks about Kishore Kumar 4 5 30. Musafir Hoon Yaron 38. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil Film: Parichay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Guide 31.