Identifying Igneous Rocks – Video Tutorial Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydrogeologic Applications for Historical Records and Images from Rock Samples Collected at the Nevada National Security Site An

A. 1,461 ft 1,600 ft 2,004.5 ft Lithology interpreted by Richard G. Warren, Comprehensive Volcanic Petrographics, LLC 2,204 ft Figure 3. Representation of rock column derived from lithologic records (A) compared with core samples and thin sections thin-section images (B–E) from the UE-19p borehole. B. Adularia (AA) – Orthoclase (a K-spar polymorph typical of granite), that has formed under hydrothermal rather than magmatic conditions. Image from 2,204 ft at 30 degrees polarization. Acmite (AC) – A Na- and Fe3-rich pyroxene typically found as a Allanite (AL) – An epidote-group mineral containing high contents groundmass phase within devitrified peralkaline rock. Image from of rare-earth elements, found in alkali-calcic volcanic rocks. Image 2,004.5 ft at 90 degrees polarization. from 1,600 ft at 30 degrees polarization. C. Biotite (BT) – A hydrated mafic mineral typical of evolved volcanic rocks. Generally lacking in peralkaline units. Image from 1,461 ft at 90 degrees polarization. Glass (GL) – Typically Ca- and Fe-poor, compositionally at the “granite eutectic” within rhyolitic rocks such as those dominant within the Southwestern Nevada Volcanic Field (SWNVF). Unpolarized image from 1,461 ft. Clinopyroxene (CX) – A Ca-rich pyroxene and anhydrous mafic mineral found in a wide variety of volcanic rocks. Image from 1,461 ft at 30 degrees polarization. D. K-feldspar (KF) – A felsic phenocryst ubiquitous as sanidine within the SWNVF, except absent within the wahmonie Formation. Image from 2,004.5 ft at 30 degrees polarization. Lithic (LI) – A rock fragment incorporated into tuff during eruption, Perrierite/Chevkinite (PE) – A pseudobrookite-group mineral usually from the vent. -

Mineralogy and Petrology of the Santo Tomas-Black Mountain Basalt Field, Potrillo Volcanics, South-Central New Mexico

JERRY M. HOFFER Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79900 Mineralogy and Petrology of the Santo Tomas-Black Mountain Basalt Field, Potrillo Volcanics, South-Central New Mexico ABSTRACT called the Santo Tomas-Black Mountain basalt field (Hoffer, 1969c). The Santo Tomas-Black Mountain basalts The Santo Tomas-Black Mountain basalt were erupted during the Quaternary from field includes four major centers, each with four centers. Six lava flows are present at one or more cones and associated flows Black Mountain, three at Santo Tomas, and (Hoffer, 1969a). From north to south, the one each at Little Black Mountain and San four volcanic centers are Santo Tomas, San Miguel. The basalts are grouped into three Miguel, Little Black Mountain, and Black major types of phenocryst mineralogy: (l) Mountain. The largest volume of lava has plagioclase abundant, (2) olivine abundant, been extruded from the Black Mountain and and (3) both olivine and plagioclase abundant. Santo Tomas centers where six and three All three types are alkali-olivine basalts, individual flows, respectively, have been showing high alkali-silica ratios and total mapped (Hoffer, 1969a). Each of the two alkali content increasing with silica. intervening centers, Little Black Mountain Seven periods of basaltic extrusion among and San Miguel, shows only a single flow. the centers have been established on the No flow from a given center coalesces with basis of field evidence, phenocryst mineralogy, those from neighboring centers, but all ap- and pyroxene-olivine ratios. K-Ar dates show pear to be closely related in time (Kottlowski, the basalts to be less than 0.3 X 106 m.y. -

Module 7 Igneous Rocks IGNEOUS ROCKS

Module 7 Igneous Rocks IGNEOUS ROCKS ▪ Igneous Rocks form by crystallization of molten rock material IGNEOUS ROCKS ▪ Igneous Rocks form by crystallization of molten rock material ▪ Molten rock material below Earth’s surface is called magma ▪ Molten rock material erupted above Earth’s surface is called lava ▪ The name changes because the composition of the molten material changes as it is erupted due to escape of volatile gases Rocks Cycle Consolidation Crystallization Rock Forming Minerals 1200ºC Olivine High Ca-rich Pyroxene Ca-Na-rich Amphibole Intermediate Na-Ca-rich Continuous branch Continuous Discontinuous branch Discontinuous Biotite Na-rich Plagioclase feldspar of liquid increases liquid of 2 Temperature decreases Temperature SiO Low K-feldspar Muscovite Quartz 700ºC BOWEN’S REACTION SERIES Rock Forming Minerals Olivine Ca-rich Pyroxene Ca-Na-rich Amphibole Na-Ca-rich Continuous branch Continuous Discontinuous branch Discontinuous Biotite Na-rich Plagioclase feldspar K-feldspar Muscovite Quartz BOWEN’S REACTION SERIES Rock Forming Minerals High Temperature Mineral Suite Olivine • Isolated Tetrahedra Structure • Iron, magnesium, silicon, oxygen • Bowen’s Discontinuous Series Augite • Single Chain Structure (Pyroxene) • Iron, magnesium, calcium, silicon, aluminium, oxygen • Bowen’s Discontinuos Series Calcium Feldspar • Framework Silicate Structure (Plagioclase) • Calcium, silicon, aluminium, oxygen • Bowen’s Continuous Series Rock Forming Minerals Intermediate Temperature Mineral Suite Hornblende • Double Chain Structure (Amphibole) -

Compositional Zoning of the Bishop Tuff

JOURNAL OF PETROLOGY VOLUME 48 NUMBER 5 PAGES 951^999 2007 doi:10.1093/petrology/egm007 Compositional Zoning of the Bishop Tuff WES HILDRETH1* AND COLIN J. N. WILSON2 1US GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, MS-910, MENLO PARK, CA 94025, USA 2SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND, PB 92019 AUCKLAND MAIL CENTRE, AUCKLAND 1142, NEW ZEALAND Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/petrology/article/48/5/951/1472295 by guest on 29 September 2021 RECEIVED JANUARY 7, 2006; ACCEPTED FEBRUARY 13, 2007 ADVANCE ACCESS PUBLICATION MARCH 29, 2007 Compositional data for 4400 pumice clasts, organized according to and the roofward decline in liquidus temperature of the zoned melt, eruptive sequence, crystal content, and texture, provide new perspec- prevented significant crystallization against the roof, consistent with tives on eruption and pre-eruptive evolution of the4600 km3 of zoned dominance of crystal-poor magma early in the eruption and lack of rhyolitic magma ejected as the BishopTuff during formation of Long any roof-rind fragments among the Bishop ejecta, before or after onset Valley caldera. Proportions and compositions of different pumice of caldera collapse. A model of secular incremental zoning is types are given for each ignimbrite package and for the intercalated advanced wherein numerous batches of crystal-poor melt were plinian pumice-fall layers that erupted synchronously. Although released from a mush zone (many kilometers thick) that floored the withdrawal of the zoned magma was less systematic than previously accumulating rhyolitic melt-rich body. Each batch rose to its own realized, the overall sequence displays trends toward greater propor- appropriate level in the melt-buoyancy gradient, which was self- tions of less evolved pumice, more crystals (0Á5^24 wt %), and sustaining against wholesale convective re-homogenization, while higher FeTi-oxide temperatures (714^8188C). -

Geology, Geochemistry, and Mineral Resources of The

GEOLOGY, GEOCHEMISTRY, AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE UPPER CAURA RIVER AREA, BOLIVAR STATE, VENEZUELA by Gary B. Sidder1 and Felix Martinez2 Open-File Report 90-231 1990 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. Denver, Colorado 2CVG-TECMIN, Ciudad Bolivar, Venezuela TABLE OF CONTENTS 'age ABSTRACT..............................^ 1 INTRODUCTION......................... 2 REGIONAL GEOLOGY......................................................................................... 4 LOCAL GEOLOGY................................................................................................. 5 Description of Rock Units................................................................... 6 Structure................................................................................................... 8 GEOCHEMSTRY.............................................^ 9 Analytical Results................................................................................. 10 ECONOMC GEOLOGY................................. 21 REGIONAL CORRELATION.............................................................................. 22 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS.................................................................... 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..........................................................................^ 26 REFERENCES CITED............................................................................................ 27 LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1. Location map and geologic sketch -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the MOUNT ADAMS VOLCANIC FIELD, CASCADE RANGE of SOUTHERN WASHINGTON by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-2460 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MOUNT ADAMS VOLCANIC FIELD, CASCADE RANGE OF SOUTHERN WASHINGTON By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein When I climbed Mount Adams {17-18 August 1945] about 1950 m (6400') most of the landscape is mantled I think I found the answer to the question of why men by dense forests and huckleberry thickets. Ten radial stake everything to reach these peaks, yet obtain no glaciers and the summit icecap today cover only about visible reward for their exhaustion... Man's greatest 2.5 percent (16 km2) of the cone, but in latest Pleis experience-the one that brings supreme exultation tocene time (25-11 ka) as much as 80 percent of Mount is spiritual, not physical. It is the catching of some Adams was under ice. The volcano is drained radially vision of the universe and translating it into a poem by numerous tributaries of the Klickitat, White Salmon, or work of art ... Lewis, and Cis pus Rivers (figs. 1, 2), all of which ulti William 0. Douglas mately flow into the Columbia. Most of Mount Adams and a vast area west of it are Of Men and Mountains administered by the U.S. Forest Service, which has long had the dual charge of protecting the Wilderness Area and of providing a network of logging roads almost INTRODUCTION everywhere else. The northeast quadrant of the moun One of the dominating peaks of the Pacific North tain, however, lies within a part of the Yakima Indian west, Mount Adams, stands astride the Cascade crest, Reservation that is open solely to enrolled members of towering 3 km above the surrounding valleys. -

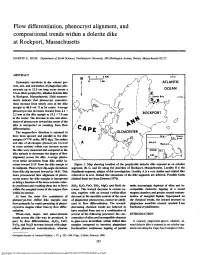

Flow Differentiation, Phenocryst Alignment, and Compositional Trends Within a Dolerite Dike at Rockport, Massachusetts

Flow differentiation, phenocryst alignment, and compositional trends within a dolerite dike at Rockport, Massachusetts MARTIN E. ROI3S Department of Earth Sciences, Northeastern University, 360 Huntington Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02115 ABSTRACT Systematic variations in the volume per- cent, size, and orientation of plagioclase phe- nocrysts up to 12.0 cm long occur across a 5.6-m-thick porphyritic, alkaline dolerite dike in Rockport, Massachusetts. Field measure- ments indicate that phenocryst concentra- tions increase froim nearly zero at the dike margin to 46.0 vol. % at its center. Average phenocryst size increases inward from 4.1 x 2.2 mm at the dike margin to 19.2 * 7.9 mm at the center. The increase in size and abun- dance of phenocrysts toward the center of the dike is interpreted as resulting from flow differentiation. The magma-flow direction is assumed to have been upward and parallel to the dike margins (N7°W strike, 88°E dip). The strikes and dips of all elongate phenocrysts (viewed in cross section) within one traverse across the dike were measured and compared to the dike attitude to determine the degree of flow alignment across I he dike. Average pheno- cryst strike deviations from dike strike in- crease inward 21.8° from the dike margin to Figure 1. Map showing location of the porphyritic dolerite dike exposed as en echelon its midpoint. Phenocryst dip-angle deviations segments (B, C, and D) along the shoreline of Rockport, Massachusetts. Locality B is the from dike dip increase inward by 18.8°. This Headlands segment, subject of this investigation. -

Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, West-Central British Columbia

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-10-24 A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia Kuehn, Christian Kuehn, C. (2014). A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25002 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1936 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia by Christian Kuehn A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS CALGARY, ALBERTA OCTOBER, 2014 © Christian Kuehn 2014 Abstract Alkaline and peralkaline magmatism occurred along the Anahim Volcanic Belt (AVB), a 330 km long linear feature in west-central British Columbia. The belt includes three felsic shield volcanoes, the Rainbow, Ilgachuz and Itcha ranges as its most notable features, as well as regionally extensive cone fields, lava flows, dyke swarms and a pluton. Volcanic activity took place periodically from the Late Miocene to the Holocene. -

Geology Along the Taylor Highway Alaska

Geology Along the Taylor Highway Alaska By HELEN L. FOSTER and TERRY E. C. KEITH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 128 1 A log describing the geology across the Yukon-Tanana Upland, Alaska UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1969 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Ubrary of Congress catalog-card No. 71-602340 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Prlntln~ Office Washln~ton. D.C. 20402 IV CONTENTS Pal:e FIGURE 13. A typical entrenched meander of South Fork of Fortymile lliver_______________________________________________ 20 14. Abandoned gold dredge_________________________________ 21 15. Plunging anticline______________________________________ 22 16. Mining on Wade CreeL________________________________ 23 17. A large meander of the Fortymile lliver___________________ 25 18. Vertical marble bed___ __ _______________ ___ _ ___ 26 19. Taylor Highway bridge across Fortymile lliver_____________ 27 20. Intricately folded marble and quartzite____________________ 28 21. Woli Mountain________________________________________ 30 22. Steep cliffs of columnar basaIL___________________________ 31 23. Ultramafic rock along the canyon of American Creek_______ 32 24. Eagle and the Yukon lliver- ____________________________ 34 TABLE Page TABLE 1. Approximate sequence and age of geologic events in the country along the Taylor Highway_____________________ 4 GLOSSARY Actinolite. A green mineral which commonly occurs in needlelike crystals. AmygdaloidaI. An adjective that describes a volcanic rock in which many small gas cavities have been filled by secondary minerals. Amygdule. A small gas cavity in a volcanic rock that has been filled with a secondary mineral such as quartz or calcite. Augen gneiss. In the Fortymile area, a gneiss which has light-gray or pink feldspar crystals that are much larger than the other crystals in the rock. -

Report 82-830, Cascades of Southern Washington Have Radiometric Ages 77 P

1.{) 0 0 C\.1 ..!. 0.. <C ~ U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF UPPER EOCENE TO HOLOCENE VOLCANIC AND RELATED ROCKS IN THE CASCADE RANGE, WASHINGTON By James G. Smith ....... (j, MISCELLANEOUS INVESTIGATIONS SERIES 0 0 Published by the U.S. Geological Survey, 1993 ·a 0 0 3: )> i:l T t'V 0 0 (J1 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-2005 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF UPPER EOCENE TO HOLOCENE VOLCANIC AND RELATED ROCKS IN THE CASCADE RANGE, WASHINGTON By James G. Smith INTRODUCTION the range's crest. In addition, age control was scant and limited chiefly to fossil flora. In the last 20 years, access has greatly Since 1979 the Geothermal Research Program of the U.S. improved via well-developed networks· of logging roads, and Geological Survey has carried out a multidisciplinary research radiometric geochronology-mostly potassium-argon (K-Ar) effort in the Cascade Range. The goal of this research is to data-has gradually solved some major problems concerning understand the geology, tectonics, and hydrology of the timing of volcanism and age of mapped units. Nevertheless, Cascades in order to characterize and quantify geothermal prior to 1980, large parts of the Cascade Range remained resource potential. A major goal of the program is compilation unmapped by modern studies. of a comprehensive geologic map of the entire Cascade Range Geologic knowledge of the Cascade Range has grown rapidly that incorporates modern field studies and that has a unified in the last few years. -

The Plumbing Systems and Parental Magma Compositions Of

THE PLUMBING SYSTEMS AND PARENTAL MAGMA COMPOSITIONS OF SHIELD VOLCANOES IN THE CENTRAL OREGON HIGH CASCADES AS INFERRED FROM MELT INCLUSION DATA by STANLEY PAUL MORDENSKY II A THESIS Presented to the Department of Geological Sciences and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science September 2012 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Stanley Paul Mordensky II Title: The Plumbing Systems and Parental Magma Compositions of Shield Volcanoes in the Central Oregon High Cascades as Inferred from Melt Inclusion Data This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Department of Geological Sciences by: Dr. Paul Wallace Chair Dr. Ilya Bindeman Member Dr. Katharine Cashman Member Dr. Dana Johnston Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2012 ii © 2012 Stanley Paul Mordensky II iii THESIS ABSTRACT Stanley Paul Mordensky II Master of Science Department of Geological Sciences September 2012 Title: The Plumbing Systems and Parental Magma Compositions of Shield Volcanoes in the Central Oregon High Cascades as Inferred from Melt Inclusion Data Long-lived and short-lived volcanic vents often form in close proximity to one another. However, the processes that distinguish between these volcano types remain unknown. Here, I investigate the differences of long-lived (shield volcano) and short- lived (cinder cone) magmatic systems using two approaches. In the first, I use melt inclusion volatile contents for shield volcanoes and compare them to published data for cinder cones to investigate how shallow magma storage conditions differ between the two vent types in the Oregon Cascades. -

Andesites on Mars: Implications for the Origin of Terrestrial Continental Crust

ANDESITES ON MARS: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE ORIGIN OF TERRESTRIAL CONTINENTAL CRUST. Paul D. Lowman Jr., Mail Code 921, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt MD 20771, USA. The Alpha Proton X-ray Spectrometer ferentiation" in Mars has been confirmed by (APXS) on the Mars Pathfinder rover the SNC meteorites. Unlike the Earth, this (Rieder et al., 1997) produced analyses in evolutionary path has not involved plate the X-ray mode of 5 rocks with chemical tectonics, beyond the initial crustal fragmen- compositions (62.0+2.7% SiO2 "soil-free tation indicated by the Valles Marineris and rock") corresponding to andesite. The similar features. APXS soil analyses resemble those from the The bulk chemical composition of the Viking landers, providing a field compari- crust of Venus is not known, although ba- son. Furthermore, the Mariner 9 mission in salts have been found by two Soviet landers. 1972 had produced thermal emission spectra However, the unimodal topography of Ve- of suspended dust indicating a composition nus, and the typically continental tectonic averaging 60+10% SiO2, corresponding to style revealed by the Magellan radar "an intermediate igneous rock"(Hanel et al., (Solomon et al., 1992), are consistent with 1972a,) and implying "substantial geo- global differentiation, but as for Mars, with- chemical differentiation of Mars." An iden- out the involvement of plate tectonic proc- tical instrument on a Nimbus satellite had esses. previously produced similar dust spectra Collectively, these discoveries imply that over Africa (Hanel et al., 1972b), which,if silicate planets can undergo early global representative of the surface, support the differentiation by igneous processes not de- similarity between the terrestrial and mar- pending on sea-floor spreading and subduc- tian crusts.