Governing the Global Public Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Law Made Silicon Valley

Emory Law Journal Volume 63 Issue 3 2014 How Law Made Silicon Valley Anupam Chander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Anupam Chander, How Law Made Silicon Valley, 63 Emory L. J. 639 (2014). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol63/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANDER GALLEYSPROOFS2 2/17/2014 9:02 AM HOW LAW MADE SILICON VALLEY Anupam Chander* ABSTRACT Explanations for the success of Silicon Valley focus on the confluence of capital and education. In this Article, I put forward a new explanation, one that better elucidates the rise of Silicon Valley as a global trader. Just as nineteenth-century American judges altered the common law in order to subsidize industrial development, American judges and legislators altered the law at the turn of the Millennium to promote the development of Internet enterprise. Europe and Asia, by contrast, imposed strict intermediary liability regimes, inflexible intellectual property rules, and strong privacy constraints, impeding local Internet entrepreneurs. This study challenges the conventional wisdom that holds that strong intellectual property rights undergird innovation. While American law favored both commerce and speech enabled by this new medium, European and Asian jurisdictions attended more to the risks to intellectual property rights holders and, to a lesser extent, ordinary individuals. -

Final Program for the ATS International Conference Is Available in Printed and Digital Format

WELCOME TO ATS 2017 • WASHINGTON, DC Welcome to ATS 2017 Welcome to Washington, DC for the 2017 American Thoracic Society International Conference. The conference, which is expected to draw more than 15,000 investigators, educators, and clinicians, is truly the destination for pediatric and adult pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine professionals at every level of their careers. The conference is all about learning, networking and connections. Because it engages attendees across many disciplines and continents, the ATS International Conference draws a large, diverse group of participants, a dedicated and collegial community that inspires each of us to make a difference in patients’ lives, now and in the future. By virtue of its size — ATS 2017 features approximately 6,700 original research projects and case reports, 500 sessions, and 800 speakers — participants can attend David Gozal, MD sessions and special events from early morning to the evening. At ATS 2017 there will be something for President everyone. American Thoracic Society Don’t miss the following important events: • Opening Ceremony featuring a keynote presentation by Nobel Laureate James Heckman, PhD, MA, from the Center for the Economics of Human Development at the University of Chicago. • Ninth Annual ATS Foundation Research Program Benefit honoring David M. Center, MD, with the Foundation’s Breathing for Life Award on Saturday. • ATS Diversity Forum will feature Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, MD, Director, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health. • Keynote Series highlight state of the art lectures on selected topics in an unopposed format to showcase major discoveries in pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine. -

Nickell Rolls to Vanderbilt Win Ahead of Him in 1977

March 6-March 16, 2003 46th Spring North American Bridge Championships Daily Bulletin Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Volume 46, Number 10 Sunday, March 16, 2003 Editors: Brent Manley and Henry Francis Mark Blumenthal is winning again Vanderbilt winners: Eric Rodwell, Jeff Meckstroth, Nick Nickell, Coach Eric Kokish, Bob Hamman, Richard Freeman and Paul Soloway. Mark Blumenthal had many years of stardom Nickell rolls to Vanderbilt win ahead of him in 1977. He was already an ACBL The Nick Nickell team broke open a close Pavlicek’s team, essentially a pickup squad Grand Life Master and World Life Master. He had match in the second quarter and went on to a 158- with two relatively unfamiliar partnerships, were already finished second in the Bermuda Bowl twice. 77 victory over the Richard Pavlicek squad in the impressive in making it to the final round. Pavlicek In 1977 he had won the Vanderbilt and also the Mott- Vanderbilt Knockout Teams. played with Lee Rautenberg, Mike Kamil, Barnet Smith Trophy. It was the second victory in the Vanderbilt for Shenkin, Bob Jones and Martin Fleisher. And then it happened. He had open heart surgery Nickell, Richard Freeman, Bob Hamman, Paul The underdogs led 31-28 after the first quarter, – three operations. Something went wrong and he Soloway, Eric Rodwell and Jeff Meckstroth. The but Nickell surged ahead with a 49-7 second set. A slipped into a coma for 30 days. His brain was par- team won for the first time in 2000, although individ- turning point in the match was a deal in which tially deprived of oxygen for a while, so when he ual team members have multiple wins in the Kamil and Fleisher reached a makable vulnerable regained consciousness he discovered he had lost the Vanderbilt. -

Stealth Authoritarianism Ozan O

A7_VAROL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 4/13/2015 3:47 PM Stealth Authoritarianism Ozan O. Varol ABSTRACT: Authoritarianism has been undergoing a metamorphosis. Historically, authoritarians openly repressed opponents by violence and harassment and subverted the rule of law to perpetuate their rule. The post- Cold War crackdown on these transparently authoritarian practices provided significant incentives to avoid them. Instead, the new generation of authoritarians learned to perpetuate their power through the same legal mechanisms that exist in democratic regimes. In so doing, they cloak repressive practices under the mask of law, imbue them with the veneer of legitimacy, and render anti-democratic practices much more difficult to detect and eliminate. This Article offers a comprehensive cross-regional account of that phenomenon, which I term “stealth authoritarianism.” Drawing on rational- choice theory, the Article explains the expansion of stealth authoritarianism across different case studies. The Article fills a void in the literature, which has left undertheorized the authoritarian learning that occurred after the Cold War and the emerging reliance on legal, particularly sub-constitutional, mechanisms to perpetuate political power. Although stealth authoritarian practices are more prevalent in nondemocracies, the Article illustrates that they can also surface in regimes with favorable democratic credentials, including the United States. In so doing, the Article aims to orient the scholarly debate towards regime practices, rather than regime -

No Monitoring Obligations’ the Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ a Story of Untameable Monsters by Giancarlo F

The Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ The Death of ‘No Monitoring Obligations’ A Story of Untameable Monsters by Giancarlo F. Frosio* Abstract: In imposing a strict liability regime pean Commission, would like to introduce filtering for alleged copyright infringement occurring on You- obligations for intermediaries in both copyright and Tube, Justice Salomão of the Brazilian Superior Tribu- AVMS legislations. Meanwhile, online platforms have nal de Justiça stated that “if Google created an ‘un- already set up miscellaneous filtering schemes on a tameable monster,’ it should be the only one charged voluntary basis. In this paper, I suggest that we are with any disastrous consequences generated by the witnessing the death of “no monitoring obligations,” lack of control of the users of its websites.” In order a well-marked trend in intermediary liability policy to tame the monster, the Brazilian Superior Court that can be contextualized within the emergence of had to impose monitoring obligations on Youtube; a broader move towards private enforcement online this was not an isolated case. Proactive monitoring and intermediaries’ self-intervention. In addition, fil- and filtering found their way into the legal system as tering and monitoring will be dealt almost exclusively a privileged enforcement strategy through legisla- through automatic infringement assessment sys- tion, judicial decisions, and private ordering. In multi- tems. Due process and fundamental guarantees get ple jurisdictions, recent case law has imposed proac- mauled by algorithmic enforcement, which might fi- tive monitoring obligations on intermediaries across nally slay “no monitoring obligations” and fundamen- the entire spectrum of intermediary liability subject tal rights online, together with the untameable mon- matters. -

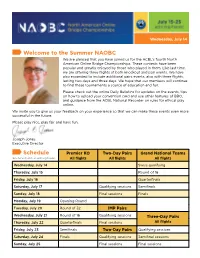

Schedule Welcome to the Summer NAOBC

Wednesday, July 14 Welcome to the Summer NAOBC We are pleased that you have joined us for the ACBL’s fourth North American Online Bridge Championships. These contests have been popular and greatly enjoyed by those who played in them. Like last time, we are offering three flights of both knockout and pair events. We have also expanded to include additional pairs events, also with three flights, lasting two days and three days. We hope that our members will continue to find these tournaments a source of education and fun. Please check out the online Daily Bulletins for updates on the events, tips on how to upload your convention card and use other features of BBO, and guidance from the ACBL National Recorder on rules for ethical play online. We invite you to give us your feedback on your experience so that we can make these events even more successful in the future. Please play nice, play fair and have fun. Joseph Jones Executive Director Schedule Premier KO Two-Day Pairs Grand National Teams See full schedule at acbl.org/naobc. All flights All flights All flights Wednesday, July 14 Swiss qualifying Thursday, July 15 Round of 16 Friday, July 16 Quarterfinals Saturday, July 17 Qualifying sessions Semifinals Sunday, July 18 Final sessions Finals Monday, July 19 Opening Round Tuesday, July 20 Round of 32 IMP Pairs Wednesday, July 21 Round of 16 Qualifying sessions Three-Day Pairs Thursday, July 22 Quarterfinals Final sessions All flights Friday, July 23 Semifinals Two-Day Pairs Qualifying sessions Saturday, July 24 Finals Qualifying sessions Semifinal sessions Sunday, July 25 Final sessions Final sessions About the Grand National Teams, Championship and Flight A The Grand National Teams is a North American Morehead was a member of the National Laws contest with all 25 ACBL districts participating. -

Ilya Shapiro (D.C. Bar #489100) Counsel of Record Trevor Burrus (D.C

Nos. 14-CV-101 / 14-CV-126 IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA COURT OF APPEALS COMPETITIVE ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE, ET AL., Defendants-Appellants, and NATIONAL REVIEW, INC., Defendant-Appellant, v. MICHAEL E. MANN, PH.D, Plaintiff-Appellee. On Appeal from the Superior Court of the District of Columbia Civil Division, No. 2012 CA 008263 B BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE CATO INSTITUTE SUPPORTING PETITION FOR REHEARING Ilya Shapiro (D.C. Bar #489100) Counsel of Record Trevor Burrus (D.C. Bar#1048911) CATO INSTITUTE 1000 Mass. Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 Tel: (202) 842-0200 Fax: (202) 842-3490 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT The Cato Institute states that it has no parent companies, subsidiaries, or affiliates, and that it does not issue shares to the public. Dated: January 3, 2019 s/ Ilya Shapiro Ilya Shapiro i TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ..................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ....................................................... 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................................................ 2 I. DISAGREEMENT WITH OFFICIAL BODIES IS NOT EVIDENCE OF BAD FAITH ................................ 2 II. CALLS FOR INVESTIGATION, COMMONPLACE PEJORATIVE TERMS, AND ANALOGIES TO “NOTORIOUS” PERSONS CANNOT BE ACTIONABLE FOR LIBEL ........................................... 6 CONCLUSION .................................................................................. -

White House Ices out CNN - POLITICO

White House ices out CNN - POLITICO http://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-cnn... WHITE HOUSE White House ices out CNN Trump administration refuses to put officials on air on the network the president called 'fake news.' By HADAS GOLD | 01/31/17 06:16 PM EST 1 of 12 02/05/2017 12:51 PM White House ices out CNN - POLITICO http://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-cnn... President Donald Trump refused to take a question from CNN correspondent Jim Acosta at a contentious Jan. 11 press conference in New York. | Getty The White House has refused to send its spokespeople or surrogates onto CNN shows, effectively freezing out the network from on-air administration voices. “We’re sending surrogates to places where we think it makes sense to promote our agenda,” said a White House official, acknowledging 2 of 12 02/05/2017 12:51 PM White House ices out CNN - POLITICO http://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-cnn... that CNN is not such a place, but adding that the ban is not permanent. A CNN reporter, speaking on background, was more blunt: The White House is trying to punish the network and force down its ratings. “They’re trying to cull CNN from the herd,” the reporter said. Administration officials are still answering questions from CNN reporters. But administration officials including White House press secretary Sean Spicer and senior counselor Kellyanne Conway haven't appeared on the network's programming in recent weeks. (Update: On Wednesday, the day after this article was published, the White House made Dr. -

DFAT Country Information Report

DFAT Country Information Report Turkey 5 September 2016 Contents Contents 2 Acronyms 3 1. Purpose and Scope 4 2. Update following July 2016 coup attempt 5 Background 5 Groups of Interest 6 Security Situation 7 3. Background Information 8 Recent History 8 Demography 8 Economic Overview 9 Political System 10 Human Rights Framework 11 Security Situation 12 4. Refugee Convention Claims 14 Race/Nationality 14 Religion 16 Political Opinion (Actual or Imputed) 22 Groups of Interest 24 5. Complementary Protection Claims 29 Arbitrary Deprivation of Life 29 Torture 29 Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment 29 6. Other Considerations 31 State Protection 31 Internal Relocation 33 Documentation 34 DFAT Country Information Report – Turkey 2 Acronyms AKP the Justice and Development Party (Turkish: Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi) BDP the Peace and Democracy Party (Turkish: Bariş ve Demokrasi PartisiI) CHP The Republican People’s Party (Turkish: Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi) DBP the Democratic Regions Party - formerly the BDP (Turkish: Demokratik Bölgeler PartisiI) DHKP-C the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (Turkish: Devrimci Halk Kurtuluş Partisi- CephesiI) Diyanet the Turkish State Directorate of Religious Affairs ECHR European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms ECrtHR the European Court of Human Rights ESP the Socialist Party of the Oppressed (Turkish: Ezilenlerin Sosyalist Partisi) GBTS The General Information Gathering System (Turkish: Genel Bilgi Toplama Sistemi) HDP The People’s Democratic Party -

Southern California Public Radio- FCC Quarterly Programming Report July 1- September 30,2016 KPCC-KUOR-KJAI-KVLA-K227BX-K210AD S

Southern California Public Radio- FCC Quarterly Programming Report July 1- September 30,2016 KPCC-KUOR-KJAI-KVLA-K227BX-K210AD START TIME DURATION ISSUE TITLE AND NARRATIVE 7/1/2016 Take Two: Border Patrol: Yesterday, for the first time, the US Border patrol released the conclusions of that panel's investigations into four deadly shootings. Libby Denkmann spoke with LA Times national security correspondent, Brian Bennett, 9:07 9:00 Foreign News for more. Take Two: Social Media Accounts: A proposal floated by US Customs and Border Control would ask people to voluntarily tell border agents everything about their social media accounts and screen names. Russell Brandom reporter for The Verge, spoke 9:16 7:00 Foreign News to Libby Denkmann about it. Law & Order/Courts/Polic Take Two: Use of Force: One year ago, the LAPD began training officers to use de-escalation techniques. How are they working 9:23 8:00 e out? Maria Haberfeld, professor of police science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice spoke to A Martinez about it. Take Two: OC Refugee dinner: After 16 hours without food and water, one refugee family will break their Ramadan fast with mostly strangers. They are living in Orange County after years of going through the refugee process to enter the United States. 9:34 4:10 Orange County Nuran Alteir reports. Take Two: Road to Rio: A Martinez speaks with Desiree Linden, who will be running the women's marathon event for the US in 9:38 7:00 Sports this year's Olympics. Take Two: LA's best Hot dog: We here at Take Two were curious to know: what’s are our listeners' favorite LA hot dog? They tweeted and facebooked us with their most adored dogs, and Producers Francine Rios, Lori Galarreta and host Libby Denkmann 9:45 6:10 Arts And Culture hit the town for a Take Two taste test. -

The Hearing-Impaired Mentally Retarded: Recommendations for Action

a DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 549 BC 073 665 AUTHOR Healey, William C.; Karp-Nortmanl,. Doreen S. TITLE The Hearing-Impaired Mentally Retarded: Recommendations for Action. 1975. SPONS AGENCY . Rehabilitation Servicfis Administration (DREW); Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 164p. ,^ -IEDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 BC-$8.24 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Aurally Handicapped; Exceptional Child Education; Exceptional Child Services; *Financial Policy; Interagency Cooperation; *Legislation; hentally Handicapped; *Multiply Handicapped; *Piogram"esign; *Program,Development; Severely Handicapped; §taff Role . ABSTRACT Recommendations for action in' serving the hearing impaired mentally retarded (HIMR) are presented by a committee composed of representatives from the American Speech and Hearing Association, the Cpnference of Executives of American Schools for the 4, Deaf, and the American Association on Mental Deficiency. The popilation is defined to include those individuals who have hearing impairment, subaverage general intellectual functioning and deficits in adaptive behavior. Reviewed re the constitutional and legal rights of 'handicapped persons, and outlined are significant federal funding provisions.affecting services to the HIMR. Problems within the existing system of services are summarized, and suggestions for program coordination (such as developm..nt of comprehensive data systems and establishment of a national information,center) are made. Prevention services and early identification are described among the aspects of a continuum of services for the HIMR. Considered in a discussion of,personnel availability and utilization are the use of interdisciplMary personnel and training programs for prof- onals and paraprofessionals. Listed are the committee's issu nd recommendations for such areas, as legislation, fina ng, administrative and organizational structure, and te ching, management and ,supervision. -

"Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1-2018 "Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House Carol Pauli Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Communications Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the President/ Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Carol Pauli, "Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House, 33 Ohio St. J. Disp. Resol. 397 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/1290 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Enemy of the People": Negotiating News at the White House CAROL PAULI* I. INTRODUCTION II. WHITE HOUSE PRESS BRIEFINGS A. PressBriefing as Negotiation B. The Parties and Their Power, Generally C. Ghosts in the Briefing Room D. Zone ofPossibleAgreement III. THE NEW ADMINISTRATION A. The Parties and Their Power, 2016-2017 B. White House Moves 1. NOVEMBER 22: POSITIONING 2. JANUARY 11: PLAYING TIT-FOR-TAT a. Tit-for-Tat b. Warning or Threat 3. JANUARY 21: ANCHORING AND MORE a. Anchoring b. Testing the Press c. Taunting the Press d. Changingthe GroundRules e. Devaluing the Offer f. MisdirectingPress Attention * Associate Professor, Texas A&M University School of Law; J.D. Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law; M.S.