The Hearing-Impaired Mentally Retarded: Recommendations for Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Program for the ATS International Conference Is Available in Printed and Digital Format

WELCOME TO ATS 2017 • WASHINGTON, DC Welcome to ATS 2017 Welcome to Washington, DC for the 2017 American Thoracic Society International Conference. The conference, which is expected to draw more than 15,000 investigators, educators, and clinicians, is truly the destination for pediatric and adult pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine professionals at every level of their careers. The conference is all about learning, networking and connections. Because it engages attendees across many disciplines and continents, the ATS International Conference draws a large, diverse group of participants, a dedicated and collegial community that inspires each of us to make a difference in patients’ lives, now and in the future. By virtue of its size — ATS 2017 features approximately 6,700 original research projects and case reports, 500 sessions, and 800 speakers — participants can attend David Gozal, MD sessions and special events from early morning to the evening. At ATS 2017 there will be something for President everyone. American Thoracic Society Don’t miss the following important events: • Opening Ceremony featuring a keynote presentation by Nobel Laureate James Heckman, PhD, MA, from the Center for the Economics of Human Development at the University of Chicago. • Ninth Annual ATS Foundation Research Program Benefit honoring David M. Center, MD, with the Foundation’s Breathing for Life Award on Saturday. • ATS Diversity Forum will feature Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, MD, Director, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health. • Keynote Series highlight state of the art lectures on selected topics in an unopposed format to showcase major discoveries in pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine. -

Nickell Rolls to Vanderbilt Win Ahead of Him in 1977

March 6-March 16, 2003 46th Spring North American Bridge Championships Daily Bulletin Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Volume 46, Number 10 Sunday, March 16, 2003 Editors: Brent Manley and Henry Francis Mark Blumenthal is winning again Vanderbilt winners: Eric Rodwell, Jeff Meckstroth, Nick Nickell, Coach Eric Kokish, Bob Hamman, Richard Freeman and Paul Soloway. Mark Blumenthal had many years of stardom Nickell rolls to Vanderbilt win ahead of him in 1977. He was already an ACBL The Nick Nickell team broke open a close Pavlicek’s team, essentially a pickup squad Grand Life Master and World Life Master. He had match in the second quarter and went on to a 158- with two relatively unfamiliar partnerships, were already finished second in the Bermuda Bowl twice. 77 victory over the Richard Pavlicek squad in the impressive in making it to the final round. Pavlicek In 1977 he had won the Vanderbilt and also the Mott- Vanderbilt Knockout Teams. played with Lee Rautenberg, Mike Kamil, Barnet Smith Trophy. It was the second victory in the Vanderbilt for Shenkin, Bob Jones and Martin Fleisher. And then it happened. He had open heart surgery Nickell, Richard Freeman, Bob Hamman, Paul The underdogs led 31-28 after the first quarter, – three operations. Something went wrong and he Soloway, Eric Rodwell and Jeff Meckstroth. The but Nickell surged ahead with a 49-7 second set. A slipped into a coma for 30 days. His brain was par- team won for the first time in 2000, although individ- turning point in the match was a deal in which tially deprived of oxygen for a while, so when he ual team members have multiple wins in the Kamil and Fleisher reached a makable vulnerable regained consciousness he discovered he had lost the Vanderbilt. -

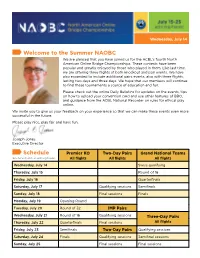

Schedule Welcome to the Summer NAOBC

Wednesday, July 14 Welcome to the Summer NAOBC We are pleased that you have joined us for the ACBL’s fourth North American Online Bridge Championships. These contests have been popular and greatly enjoyed by those who played in them. Like last time, we are offering three flights of both knockout and pair events. We have also expanded to include additional pairs events, also with three flights, lasting two days and three days. We hope that our members will continue to find these tournaments a source of education and fun. Please check out the online Daily Bulletins for updates on the events, tips on how to upload your convention card and use other features of BBO, and guidance from the ACBL National Recorder on rules for ethical play online. We invite you to give us your feedback on your experience so that we can make these events even more successful in the future. Please play nice, play fair and have fun. Joseph Jones Executive Director Schedule Premier KO Two-Day Pairs Grand National Teams See full schedule at acbl.org/naobc. All flights All flights All flights Wednesday, July 14 Swiss qualifying Thursday, July 15 Round of 16 Friday, July 16 Quarterfinals Saturday, July 17 Qualifying sessions Semifinals Sunday, July 18 Final sessions Finals Monday, July 19 Opening Round Tuesday, July 20 Round of 32 IMP Pairs Wednesday, July 21 Round of 16 Qualifying sessions Three-Day Pairs Thursday, July 22 Quarterfinals Final sessions All flights Friday, July 23 Semifinals Two-Day Pairs Qualifying sessions Saturday, July 24 Finals Qualifying sessions Semifinal sessions Sunday, July 25 Final sessions Final sessions About the Grand National Teams, Championship and Flight A The Grand National Teams is a North American Morehead was a member of the National Laws contest with all 25 ACBL districts participating. -

4788.5 Tables Championship Day in Atlanta

Monday, August 5, 2013 Volume 85, Number 4 Daily Bulletin 85th North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley, Paul Linxwiler and Sue Munday Championship Day in Atlanta Photos only for NABC events today. Full reports will appear later this week. ACBL Hall of Fame story and photos will appear in the Tuesday edition. District 9 repeats as winners of the Championship Flight: Eric Rodwell, David Berkowitz, Jeff Meckstroth, Michael Becker, captain Warren Spector and Gary Cohler. Mark Itabashi and Ross Grabel: winners of the von Zedtwitz Life Master Pairs. District 22 won the Goldman Flight A by a single IMP: Bo Liu, Xiao-yan Gong, Weishu Wu, captain Soichi Yoshihiro and Philip Hiestand. Randy Thompson and Barry Spector won the Bruce LM-5000 Pairs. Winners of the Sheinwold Flight B from District 11: (front) Lori Harner and Donna Moore; (back) William Gottschall, captain Joseph Keim, Larry Jones and Douglas Millsap. Alan Hierseman and Doug Fjare won the Young District 23 Life Master 0-1500 Pairs by 1.57 matchpoints. captured the MacNab Flight C crown: Yichi WBF reports inside Zhang, Om Today and through the end of the tournament, Chokriwala, the middle four pages of the Daily Bulletin include Nolan Chang, reporting from the World Youth Open Bridge Fred Upton and Championships. Jack Chang. ATTENDANCE through Sunday afternoon 4788.5 tables Page 2 Monday, August 5, 2013 Daily Bulletin SPECIAL EVENTS MEETINGS / SEMINARS / RECEPTIONS Monday, August 5 tournament information system.B Atrium Tower, level 2, 9–11 a.m. ACBLScore+. Atrium Tower, level 2, Conference Suite 222. Conference Suite 222. -

Two Major Upsets in Spingold KO Showdown Time in Wagar Teams

July 8-18, 2004 76th Summer North American Bridge Championships DAILY BULLETIN New York, New York Volume 76, Number 6 Wednesday, July 14, 2004 Editors: Brent Manley and Henry Francis Two major upsets in Spingold KO Teams captained by Rose Meltzer and Rita Shugart are on the sidelines today as the third round of play gets underway in the Spingold Knockout Teams. Meltzer’s all-star squad – Kyle Larsen, Peter Weichsel, Alan Sontag, Chip Martel and Lew Stansby – fell to the No. 61 seed, an all-England team captained by Jack Mizel. Meltzer jumped out to a 48-13 lead after the first quarter but were blasted 52-5 in the second quarter and never recovered as they dropped a 135-88 decision. Mizel played with Alexander Allfrey, Arthur Malinowsky and Andrew McIntosh. By contrast to the other match, Shugart held a 41-IMP lead with a quarter to go but were Welland tries harder, outscored 53-8 by a New York-Canada team led by Fred Hoffer. The final score was 140-136. but he’s not No. 2 Hoffer, of Cote Saint-Luc in Quebec, and As a games player from an early age, Roy fellow Canadian Don Piafsky of Toronto were Welland has always set high standards for himself. playing with New Yorkers Barry Piafsky, Allen “I’m a bit of a perfectionist,” says the 41-year- Kahn and David Rosenberg. old New Yorker. “If I do something, I try to do it as In another upset, the No. 15 seed, captained by The time has come well as humanly possible.” Bart Bramley, lost a close match to the team led by For Welland the bridge player, “as well as for Intellympics Phillip Becker. -

Mcnamara, Clifford, Burdens of Vietnam 1965-1969

Secretaries of Defense Historical Series McNamara, Clifford, and the Burdens of Vietnam 1965-1969 SECRETARIES OF DEFENSE HISTORICAL SERIES Erin R. Mahan and Stuart I. Rochester, General Editors Volume I: Steven L. Rearden, The Formative Years, 1947-1950 (1984) Volume II: Doris M. Condit, The Test of War, 1950-1953 (1988) Volume III: Richard M. Leighton, Strategy, Money, and the New Look, 1953-1956 (2001) Volume IV: Robert J. Watson, Into the Missile Age, 1956-1960 (1997) Volume V: Lawrence S. Kaplan, Ronald D. Landa, and Edward J. Drea, The McNamara Ascendancy, 1961-1965 (2006) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Includes bibliography and index. Contents: v. l. The formative years, 1947-1950 / Steven L. Rearden – v. 2. The test of war, 1950-1953 / Doris M. Condit – v. 3. Strategy, money, and the new look, 1953-1956 / Richard M. Leighton – v. 4. Into the missile age, 1956-1960 / Robert J. Watson – v. 5. The McNamara ascendancy, 1961-1965 / Lawrence S. Kaplan, Ronald D. Landa, and Edward J. Drea. 1. United States. Dept. of Defense—History. I. Goldberg, Alfred, 1918- . II. Rearden, Steven L., 1946- . III. Condit, Doris M., 1921- . IV. Leighton, Richard M., 1914-2001. V. Watson, Robert J., 1920- 2010. VI. Kaplan, Lawrence S., 1924- ; Landa, Ronald D., 1940- ; Drea, Edward J., 1944- . VII. United States. Dept. of Defense. Historical Office. UA23.6.R4 1984 353.6’09 84-601133 Foreword Volume VI of the Secretaries of Defense Historical Series covers the last four years of the Lyndon Johnson administration—March 1965–January 1969, which were dominated by the Vietnam conflict. -

Brod Squad Wins Senior Swiss This Is a Continuing Series of Profiles of a Connecticut Team Captained Tournament Directors Working at the Nabcs

Volume 78, Number 6 78th Summer North American Bridge Championships DAILY BULLETIN Wednesday, July 19, 2006 Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Meet your TDs Brod squad wins Senior Swiss This is a continuing series of profiles of A Connecticut team captained tournament directors working at the NABCs. by Geof Brod came from behind Long before he became a tournament director, on the last round, climbing over Jim Chiszar observed three teams to win the Truscott the TDs at work and USPC Senior Swiss Teams by 1 thought it looked like victory point. something he would Brod and his partner, Steve enjoy doing. Earl, are from Avon CT. Their Later, when he teammates are Richard started in the DeMartino of Riverside CT and profession, he was John Stiefel of Wethersfield CT. surprised to find that With a round to go, the Brod TDs receive money in team had 104 VPs, trailing the exchange for their Michael Mikyska squad, the time and efforts. eventual runners-up, by 8. “I just wanted to do it,” he says. “I didn’t know Another team had 108.2 and a they got paid.” third had 104.3 Senior Swiss teams winners: Geof Brod, Steve Earl, Richard Chiszar, who lives in the Chicago suburb of Brod won their last match DeMartino and John Stiefel. Naperville, is winding down his long and successful 15-0 to get 16 VPs while Mikyska lost and is a consulting actuary and DeMartino is a retired career. He and wife Patty are set to retire at the end collected only 7. -

Peter Mollemet Harry Lampert

November 18-28, 2004 78th Fall North American Bridge Championships Daily Bulletin Orlando, Florida Volume 78, Number 1 Friday, November 19, 2004 Editors: Brent Manley and Henry Francis Seniors win gold in World Games Led by a Senior team and Zia Mahmood, the USA scored several medals during the world championships in Istanbul, Turkey. The tournament concluded Nov. 6. With a big final-round victory over Denmark, USA went from second to first in the 2nd International Senior Cup. The team was John Onstott, Jim Robison, John Schermer, Neil Chambers, Marshall Miles and Leo Bell. Gene Freed was non-playing captain. The format was a complete round-robin with no knockout phase. Harry Lampert In the Women’s series of the 12th World Bridge Harry Lampert, a noted cartoonist who retired in Olympiad, the USA dropped a close decision to 1976 and built a second career as a bridge writer and Russia in the final to earn the silver medal. The Peter Mollemet teacher, died Nov. 13 at Boca Community Hospital in team was Marinesa Letizia, Jill Meyers, Randi Boca Raton FL. He was 88. The cause of death was a Montin, Janice Seamon-Molson, Tobi Sokolow and Longtime ACBL employee Peter Mollemet cerebral hemorrhage, his family said. Carlyn Steiner. Jill Levin was npc. died of heart failure Nov. 18 in Memphis. The 61- Lampert entered the cartoon field in 1933 Zia earned a gold medal and his first world year-old Mollemet, who had battled heart problems where he did inking for cartoons including Popeye, championship as a member of the winning squad in for years, arrived for work at ACBL Headquarters Betty Boop and Koko the Clown. -

He Just Can't Stop Writing WBF Tournament in the US

Friday, March 20, 2009 Volume 52, Number 8 Daily Bulletin Houston, Texas 52nd Spring North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Dave Smith WBF tournament in Cayne and Diamond rally, make Vanderbilt the U.S. ‘possible’ semifinals Buoyed by a commitment from Tracy and Lou $50,000 to the United States Bridge Federation to Teams captained by John Diamond and James Ann O’Rourke, forces are at work to convince the help make the tournament on American soil Cayne came from behind to make it to the semifinal World Bridge Federation that the 2010 world possible. round of the Vanderbilt Knockout Teams. championships should be scheduled in the United WBF President Jose Damiani, visiting Houston Cayne trailed the John Sutherlin team by 10 States. to discuss the possibilities, said that he is hopeful his IMPs with 16 boards to play but won the final set The O’Rourkes, who celebrated their 54th organization, the USBF and the ACBL “will find a 54-23 to earn a berth in the semifinals against the wedding anniversary on Thursday, have pledged solution.” Ralph Katz squad. Katz held a 138-60 lead over the The 2010 World Jacek Pszczola squad after three quarters when the Championships are the most latter withdrew. open of the WBF Continued on page 4 international tournaments. There are no team trials to Canadians lead IMP Pairs determine competitors, and Two players from opposite ends of Canada all events are transnational: take a slim lead into today’s two final sessions of teams and pairs can be made the Lebhar IMP Pairs. -

Recursive Diamond Notes

Recursive Diamond Notes Adam Meyerson and Sam Ieong July 23, 2004 1 General Principles The Recursive Diamond is a precision-like system, featuring light limited open- ings, weak notrumps, and an artificial forcing bid (1♦). In contrast to precision and many other systems, the focus is on accurate game and partscore bidding rather than finding slams. We tend to enter the auction aggressively on distri- butional hands and our methods emphasize exploring for the best fit rather than setting up an early game force. Our defensive bidding methods similarly em- phasize finding our best fit, showing many types of two-suited hands as quickly as possible. The opening structure of recursive diamond is as follows: 2NT at least 5-5 in the minors, weak (typically 7-10 hcp) 2♥ ♠ weak two 2♣ ♦ intermediate, rule of 20 opener, 6+ cards in bid suit 1NT 10-12 if 1st/2nd NV, else 12-14, can include 5-card major 1♥ ♠ 5 card major, rule of 18 opener, not 5332 shape 1♦ any 16+ hcp; 17+ if balanced and not 1st/2nd seat NV 1♣ 11-16 hcp, balanced or three suiter or minors Bids of 3♣ and above are standard preempts. We frequently preempt three of a minor on reasonable six-card suits, but other three-level preempts are almost always seven. 2 Major Suit Openings Major suit openings at the one level promise five cards in the bid suit. We will treat any 5332 hand with a five card major as balanced, and open in the corresponding notrump range (1NT or 1♣ or 1♦). -

2016Abaiprogbk Web.Pdf

42 nd Annual Convention Friday, May 27 to Tuesday, May 31, 2016 ABAI is a nonprofit membership organization with the mission to contribute to the well-being of society by developing, enhancing, and supporting the growth and vitality of the science of behavior analysis through research, education, and practice. 1 We Are Autism Health Specialists. At Caravel Autism Health, we believe that every child with autism deserves an independent, happy life and to connect with the world. Helping children on the autism spectrum and their families is our singular focus. The Caravel Approach We work in partnership with families to design customized autism treatment programs. Our programs are rooted in the principles of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy. We create real-world learning experiences that help children on the autism spectrum build a wide range of skills. Lund Van Dyke Changed Its Name to Caravel in January 2016. Our team of autism health professionals and our commitment to helping families living with autism remain the same. WE CHANGE LIVES. To learn more visit www.caravelautism.com or call 844-583-5437 2017 PARIS ABAI Ninth International Conference November 14–15 3 Save the date! January 31–February 2, 2017 11th Annual Autism Conference San Juan, Puerto Rico www.abainternational.org/events/autism-2017 4 Acknowledgements Program Board Coordinator Mark A. Mattaini, DSW (Jane Addams College of Social Work, University of Illinois at Chicago) Program Committee Chair Federico Sanabria, Ph.D. (Arizona State University) Program and Convention Management and CE Coordination for APA Maria E. Malott, Ph.D. (Association for Behavior Analysis International) CE Coordination for BACB Richard W. -

DAILY BULLETIN Co-Editors: Micke Melander, Barry Rigal, David Stern Lay-Out Editor: Monika Kümmel • Photos: Francesca Canali

SANYA CHINA 10TH 25TH OCTOBER 2014 Coordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer • Editors: Mark Horton, Brent Manley DAILY BULLETIN Co-Editors: Micke Melander, Barry Rigal, David Stern Lay-Out Editor: Monika Kümmel • Photos: Francesca Canali Issue No. 9 Sunday, 19th October 2014 WHEN ONE DOOR CLOSES . Gone are the chances for victory in the Mixed Teams and Mixed Pairs – those events have concluded – but players awoke to new challenges on Saturday in the form of the Rosenblum Cup, McConnell Cup and Rand Senior Teams. The Rosenblum (open) attracted 123 teams, with more than a few featuring stars of the game. The same can be said for the 26 Women’s Teams playing for the McConnell Cup and the 22 squads in the Rand Senior Teams. Some of the favored teams in the Rosenblum got off to slow starts but had rallied by the end of the seven-board matches to move solidly into qualifying position. The top 64 teams will qualify to Semi-Final A, the rest to Semi-Final B. Note the difference in the number of matches to be played in todays Women’s (nine matches) and Seniors (the first seven). Today’s Schedule On Saturday, four WBF executives, led by President Gianarrigo Rona, played a MGM Sheraton special bridge match with several Chinese university students. In the bottom Women Teams photo, Rona congratulates one of his opponents. Open Teams Seniors Teams Semifinals A&B 9:30 - 10:30 W, S Watching bridge in Sanya 9:30 - 10:30 If you want to watch the bridge play during 14th Red Bull World 10:45 - 11:45 W, S 10:50 - 11:50 Bridge Series, here's how you do it on OurGame: