Hayes Gordon, Zika Nester, Henri Szeps and the Transformations of Australian Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opera Australia 2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT Cover image: Simon Lobelson as Gregor in Metamorphosis, which played at the Opera Australia Scenery Workshop in Enriching Australia’s Surry Hills and the Malthouse cultural life with Theatre in Melbourne. exceptional opera. One of Opera Australia’s new Vision productions, it was written by Australian Brian Howard, performed by an all Australian cast To present opera that excites and produced by an all Australian audiences and sustains and creative team. Photo: develops the art form. Prudence Upton Mission TABLE OF CONTENTS At a glance 3 Artistic Sydney Screens on stage 32 Director’s Report 12 Conservatorium Productions: of Music 2018 awards 34 performances and Regional Tour 13 Internships 23 attendances 4 China tour 36 Regional Student Professional and Artists 38 Season star ratings 5 Scholarships 16 Talent Development 24 Orchestra 39 Revenue and expenditure 6 Schools Tour 18 Evita 26 Philanthropy 40 Australia’s biggest Auslan Handa Opera arts employer 7 shadow-interpreting 20 on Sydney Harbour – Opera Australia Community reach 8 Community events 21 La Bohème 28 Capital Fund 43 Chairman’s Report 10 NSW Regional New works Staff 46 Conservatoriums in development 30 Partners 48 Chief Executive Project 22 Officer’s Report 11 opera.org.au 2 At a glance 77% Self-generated revenue $61mBox office 1351 jobs provided 543,500 58,000 attendees student attendees 7 637 productions new to Australia performances opera.org.au 3 Productions Productions Performances Attendance A Night at the Opera, Sydney 1 2,182 Performances and total attendances Aida, Sydney 19 26,266 By the Light of the Moon, Victorian Schools tour 85 17,706 Carmen, Sydney 13 18,536 Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Melbourne 4 6,175 Don Quichotte, Melbourne 4 5,269 Don Quichotte, Sydney 6 7,889 Great Opera Hits 2018 27 23,664 La Bohème, Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour 26 48,267 La Bohème, Melbourne 7 11,228 La Bohème, New Year 1 1,458 The chorus of Bizet’s Carmen, directed by John Bell. -

TPI JUNE 2019Web.Indd

Volkswagen - experience one for yourself. Support the dealer who supports your association BOTH WITH NEW CAR WARRANTY TILL 2024^ Golf Golf Alltrack MY19 Golf 110TSI Trendline 7 Speed DSG MY19 Golf Alltrack from $23,888 drive away* from $33,888 drive away* • Service once a year/15,000kms • 12 year anti-corrosion perforation warranty • German quality engineering • 6 years fixed price servicing • 5 year/Unlimited kms warranty • Five star safety rating Your Volkswagen Partner John Hughes 61 Shepperton Road, (Cnr Rushton St.) Just over the Causeway, Victoria Park. Ph: 9415 0077 *Drive away prices include dealer delivery, 12 months registration, 12 months concessional licence and Stamp Duty exempt. Metallic paint extra. ^Conditions and exclusions apply, see www.volkswagen.com.au/en/owners/warranty. html. Warranty on demonstrator vehicles only applies for the balance of the 5 year term. Your rights under this warranty are provided in addition to, and in some cases overlap with, consumer guarantees under Australian Consumer Law and do not limit or replace them. THE AUSTRALIAN FEDERATION OF TOTALLY AND PERMANENTLY INCAPACITATED EX-SERVICEMEN AND WOMEN WEST AUSTRALIAN BRANCH (INC.) ABN 12 132 660 291 PRESIDENT OFFICE BEARERS PATRON John Kelly The Honourable Kim Beazley AC VICE PRESIDENT Ray Pearce JP VICE PATRONS SECRETARY Mr John Hughes Paul (Reg) Livermore FEDERAL DIRECTORS ASSISTANT SECRETARY Mr John Kelly Vacant Mr Colin Benporath TREASURER JUSTICE OF THE PEACE Dennis Gilmore Mr Ray Pearce JP 0421 122 147 ASSISTANT TREASURER [email protected] -

A Panel Discussion of Freud's Last Session

MEDIA RELEASE August 20, 2013 SEX, GOD & THE WARDROBE - A PANEL DISCUSSION OF FREUD’S LAST SESSION “Things are only simple when you choose not to examine them” – Freud’s Last Session Following the performance of the hit play Freud’s Last Session on Sunday September 1 at 3pm, the audience is invited to stay and hear Dr Rachael Kohn, Peter FitzSimons, Dr Tanveer Ahmed and Roy Williams discuss God, sex and the other simple things of life. Freud’s Last Session centres on legendary psychoanalyst Dr Sigmund Freud (played by Henri Szeps), who invites a young, little-known professor, C.S. Lewis (Douglas Hansell), to his home in London. Lewis, expecting to be hauled over the carpet for satirizing Freud in a recent book, soon realizes Freud has a much more significant agenda. On the day England enters World War II (3 September 1939), Freud and Lewis clash on the existence of God, love, sex and the meaning of life – only a few weeks before Freud chooses to take his own. The Panel Discussion will be moderated by Dr Rachael Kohn, producer and presenter of ABC Radio National’s The Spirit of Things, and the panelists will be: • Peter FitzSimons – journalist, author and atheist • Dr Tanveer Ahmed – psychiatrist and author • Roy Williams – lawyer and author of books including In God They Trust?, a study of the religious beliefs of Australia’s Prime Ministers since 1901. Inspired by Dr Armand S. Nicholi Jr's 2003 book The Question of God, playwright Mark St. Germain has expertly crafted a thought provoking play, which ran Off-Broadway for two years and now Sydney audiences and critics alike are acclaiming the play. -

Reg Livermore

REG LIVERMORE 26 JULY – 1 SEPTEMBER 2018 WELCOME WE HOPE YOU ENJOY THE WIDOW UNPLUGGED There are three reasons I wanted to direct Reg Livermore doesn’t need to prove Reg Livermore in his brand new play: anything; he has earned all the highest 1. Reg Livermore. of accolades; his peers love him; he is a 2. Reg Livermore legendary performer. He writes plays like 3. Reg Livermore. THE WIDOW UNPLUGGED and performs plays with characters like Arthur Kwick (with As an actor Reg has that beautiful quality a KW) because he wants to. That’s what all the best actors have of making the art he does. That is his life. And for me and for of acting look effortless; but you know every the many audiences who will experience moment is considered and reconsidered, this latest play from his wickedly funny every phrase planned, every throwaway imagination, we are grateful Reg is presenting rehearsed. his latest solo work for our 60th year. As As a writer he is as creative as Beckett and as part of our continuing commitment to new absurd as Patrick White but all with his own comedy I hope you will enjoy the master of brilliantly unique comedy voice. them all: Reg Livermore. As a human being he is inspirational in his Mark Kilmurry drive, his excellence and his commitment to Artistic Director a theatrical life. WRITER'S NOTE Growing older, arriving at an age where The play is not intended as a biographical one’s sense of personal relevance is statement, my own career has been much often dramatically tested is an ominous more successful than Arthur’s particular predicament for many, I’m sure. -

Theatre Programs

Theatre programs Box Id Title Author Director Cast Date Place of production Theatre Theatre Company Holdings EPH101 8 Black, Dustin Myles, Bruce Bell, Nicholas; Griffiths, Rachel; 8 June Melbourne, Vic, Her Majesty's MOMO Program (x2) Lance Parker, Georgie; McLaren, 2012 - 9 Australia Theatre Spencer; Martin, Tony; June 2012 McClements, Catherine; Blake, Rachel; MacPherson, Daniel; Crewes, Martin; Davis, Blake; Wardrop, Rob; Jacobson, Shane; Grantley, Gyton; Szubanski, Magda; Clayson, Luke; McCune, Lisa; Whitbread, Kate; Tredinnick, David; McLaren, Angus; Shaw, Julian; Laga'aia, Jay; Wong, Anthony Brandon EPH101 33 Powning, Alistair; Atkinson, Gemma; Booth, June 2011 - Darlinghurst, NSW, The TAP GALLERY Cathode Ray Tube Flyer Booth, Michael Michael; Dalton, Ben; July 2011 Australia Donoghue, Jessica; Powning, Alistair; Stewart, Emily EPH101 10CS 17 June Brunswick, Vic, Mechanics Institute Metanoia Flyer 2015 - 27 Australia Performing Arts June 2015 Centre EPH101 1985 Scandals, The Archer, Robyn Archer, Robyn; Archer, Robyn; Gaden, John; September Surry Hills, NSW, Downstairs Theatre, (devised by) Gaden, John Bell, Andrew; Vilder, Yantra De 1985 - Australia; Fitzroy, Belvoir St; Universal November Vic, Australia Theatre 1985 EPH101 2 boys in a bed on a cold Parker, James Adams, Brett Davies, John K; Clark, Andrei 22 May South Yarra, Vic, St Martins Theatre Priceless Productions Program winter's night Edwin 1997 - 14 Australia June 1997 EPH101 25 frames: beyond the porn McGreal, Kevin Hunter, Tim McGreal, Kevin; Hansen, Jude; 22 January -

Collection Name

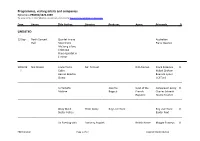

Programmes, visiting artists and companies Ephemera PR8492/1870-1899 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia Date Venue Title Author Director Producer Agent Principals D UNDATED 23 Sep Perth Concert Quartet in one Australian Hall Movement Piano Quartet My Song is love Unknown Piano Quartet in C minor 1890-95 Not Stated Uncle Tom's Mr. Trimnel N.D.Aikman Frank Bateman 0 ? Cabin. Mabel Graham Harriet Beecher Beatrice Lyster Stowe J.Clifford ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Le Tartuffe Jean De Govt of the Genevieve Leomy 0 Moliere Regault French Charles Schmitt Republic Giselle Tourtet ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Betty Blokk- Peter Batey Reg Livermore Reg Livermore 0 Buster Follies Baxter Funt ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ An Evening with Anthony Asquith British Home Margot Fonteyn 0 PR8492/UND Page 1 of 19 Copyright SLWA ©2011 Programmes, visiting artists and companies Ephemera PR8492/1870-1899 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia Date Venue Title Author Director Producer Agent Principals D the Royal Ballet Entertainment Rudolf Nureyev Ltd ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Fabian Lee Gordon Lee Gordon -

'NINE' - the "'Ultimate" Musical for Melbourne

JUNE.JULY,1987, Vol12 No 3 ISSN 0314 -3058 A publication of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust 'NINE' - The "'Ultimate" Musical for Melbourne 'NINE' by Arthur Kopit Music and lyrics by Maury Yeston Directed by fohn Diedrich Musical Director Conrad Helfrich Choreography and Staging by fo·anne Robinson and Tony Bartuccio Cast includes fohn Diedrich, Nancy Hayes, Peta Toppano, Maria Mercedes Comedy Theatre "NINE is a true original ... a marvellous musical ... theatrically and visually NINE is a stunner ... combining outrageous pizzazz with chic and good taste. It is magic ... you must see NINE" Clive Barnes, New York Post he winner of five Tony Awards on T Broadway, including Best Musical of 1~82, the Australian premiere of 'NINE' i~ coming to Melbourne. Billed as "the Ultimate Musical', 'NINE' is the culmination of a dream for John Deid rich who has assembled an amllzing array of Australian talent for this most highly praised musical. 'NINE' is based on Fellini's classIc flim "81f2" which tells the story of an Italian film director, Guido Contini and his search for happiness, honesty and love amongst the twenty-one women in his life. As well as directing the production John Diedrich plays the leading role of Contini, his first musical appearance since playing Curly in 'OKLAHOMA!'. Joining him on stage are twenty-one of Australia's most beautiful and talented actresses including Nancye Hayes, Maria Mercedes, Peta Toppano and Caroline Gillmer. This Australian pro BOOKING INFORMATION duction will have a new set designed by Commences Saturday July 11 Shaun Gurton and costumes by Roger Mon to Sat 8.00pm Wed and Sat matinees at 2.00pm Kirk with original choreography and AETI Mon , Tues $30 staging by Jo-anne Robinson (of Wed, Thurs $33 'CATS') and Tony Bartuccio. -

Collection Name

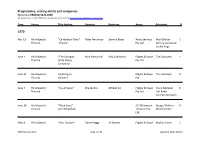

Programmes, visiting artists and companies Ephemera PR8492/1870-1899 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia Date Venue Title Author Director Producer Agent Principals D 1970 Mar 13 His Majesty's "Canterbury Tales" Peter Narroway Sammy Bayes Aztec Services Max Obistan 1 Theatre Chaucer Pty Ltd Johnny Lockwood Evelyn Page ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ June 1 His Majesty's "The Georgian Nina Ramishvili Iliko Sukhishvili Edgley & Dawe The Company 1 Theatre State Dance Pty Ltd Company" ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ June 11 His Majesty's Anything to Edgley & Dawe The Company 0 Theatre Declare? Pty ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ June ? His Majesty's "Joy of Spain" Pila de Oro Alfredo Gil Edgley & Dawe Diana Marquez 0 Theatre Pty Ltd Luis Reda Carmelo Montero ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ June 26 His Majesty's "Plaza Suite" J.C.Williamson Googie Withers 0 Theatre John McCallum Theatres Pty Alfred Sandor Ltd ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Sept 4 His Majesty's "Don Quixote" Dame Peggy Sir Robert Edgley & Dawe Marilyn Jones 1 PR8492/1970-1979 Page 1 of 33 Copyright SLWA ©2011 -

PLAY HARDER the First 50 Years of the Old Haileyburians’ Amateur Football Club 1961 - 2010

Abbott Allen Allison Anderson Armstrong Atkinson Baker Bannon Barker Baxter Bean Bell Bennett Billings Bingham Boag Bode Bonwick Bouris Bourke Bowden Bowman Bowring Brandham Brewer Broadbent Brooks Brown Brudar Buchanan Burke Burns Byrns Caddy Campbell Carson Carty Caspers Chambers Chegwin Chipperfield Chisholm Clarke Clydesdale Cocks Code Collins Connell Connolly Constable Corrigan Cotton Cox Criticos Cunningham Currie Dangerfield Dann Davey Deller Derham Dimond Dobson Dolman Dowsing Doyle Eagle Edwards Efstathiou Elliot Elliott Ellis Erikson Evans Farr Ferguson Finlayson Fletcher Flockart Floyd Forbes Ford Gadsden Galt Gartner George Gerny Gilby Gilchrist Gill Glanville Gopu Goulden Gregson Hampton Hare Harrison Harrop Hassett Hattam Hayes Henderson Herbert Hill Hilton Hodge Holohan Home Houghton Houston Irving Jackson Jayasekera Jenke Johnson Johnston Jones Jury Kejna Kellock Kight Kingsley Kingston Kirkwood-Scott Korlos Krause Ladd Ladds Lambert Lane Langford Langford-Jones Lappage Lasscock Latrielle Lavender Lay Legge Lingard Lord Lovig Lucas Lyon MacFarlane Mackay Mackenzie McKenzie Main March Marshall Mason Mattingley Mayes McCready McDonnell McGorlick McLauchlan McLean McLennan McQueen Meadows Mears Meckiff Meehan Mehegan Melin Merrett Metherall Miller Mitchell Mohammad Morey Mosbey Mountford Moyle Mueller Mulvey Mytton Neville Newton Norton Noske Oaten O’Donnell O’Farrell Orton Parkes Parton Passalaqua Paul Phillips Pitcher Plecher Pollock Poole Pound Pountney Pritchard Quick Rae Rankine Ray Reed Regan Reid Richardson Ridoutt -

Australia's Magazine of the Performing Arts 3(12) July 1979 Robert Page Editor

University of Wollongong Research Online Theatre Australia 7-1979 Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 3(12) July 1979 Robert Page Editor Lucy Wagner Editor Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia Recommended Citation Page, Robert and Wagner, Lucy, (1979), Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 3(12) July 1979, Theatre Publications Ltd., New Lambton Heights, 50p. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia/32 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 3(12) July 1979 Description Contents: Comment Quotes and Queries Whispers, Rumours and Facts Letters Guide — Theatre, Opera, Dance Richard Wherrett — nI terviewed by Rex Cramphorn Glynne — The am n behind the G &S tour — Raymond Stanley 1979 National Playwrights’ Conference — Douglas Flintoff alcF on Island — Terry Owen Children’s Theatre: Theatre in Education — Ardyne Reid Come Out 79 — Andrew Bleby Flying Fruit Fly Circus — Iain McCalman Children's Theatre in America — Christine Westwood Big Business and the Arts Part 1 — TA Enquiry Writer’s View: Clem Gorman A Sense of Insecurity — Ken Longworth Proliferation of Secret Britain Plays — Irving Wardle Let’s Make; Secret Marriage; D'Oyly Carte — David Gyger Coppelia — William Shoubridge The Queensland Ballet's Autumn Season — Deborah Reynolds ACT Losers — Solrun Hoaas NSW The -

Literature Review

The impact of the counterculture on Australian cinema in the mid to late 20th century A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Art Administration (Hons) within the School of Art History and Art Education, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Fiona Hooton 1 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hooton First name: Fiona Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: School of Art History and Art Education Faculty:COFA Title: The impact of the counterculture on Australian cinema in the mid to late 20th century 2 Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis discusses the impact of the counterculture on Australian cinema in the late 20thcentury through the work of the Sydney Underground Film group, Ubu. This group, active between 1965 -1970, was a significant part of an underground counter culture, to which many young Australians subscribed. As a group, Ubu was more than a rat bag assemblage of University students. It was an antipodean aspect of an ongoing artistic and political movement that began with the European avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century and that radically transformed artistic conventions in theatre, painting, literature, photography and film. Three purposes underpin this thesis: firstly to track the art historical links between a European avant-garde heritage and Ubu. Experimental film is a genre that is informed by cross art form interrelations between theatre, painting, literature, photography and film and the major modernist aesthetic philosophies of the last century. -

New Fair Lady

MAY, 1988 Vol 12 No 4 ISSN 0314 - 0598 Including Annual Report 1987 and Notice of Annual General Meeting A publication of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust Madge Ryan, Noel Ferrier and Helen Buday in the VOC production of MY FAIR LADY New Fair Lady - Revival of a Classic MY FAIR LADY MY FAIR LADY has all a musical Trust Members should note that Book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner should - breathtaking sets, lavish cos special concession prices apply only to Music by Frederick Loewe tumes, wonderful music and an all-star the first four weeks ' of the season. We Directed by Rodney Fisher cast. It features a twenty-piece orches regret the lateness in announcing this Cast: John Waters, Noel Ferrier, Simon tra conducted by Andrew Greene, who show as a result of protracted nego Gallaher, June Bronhill, Helen Buday is also the musical director, and a cast tiations with the producers for accept of forty, including some of Australia's able arrangements for Trust Members. ho hasn't read or at least heard of As a result, we do advise Members that George Bernard Shaw's most talented performers. Helen W Buday, who performed in MAD MAX they will obtain the best seats if they "Pygmalion" - the classic tale of a order tickets during the two weeks from Cockney flower seller who became a III and FOR LOVE ALONE, will play Eliza and Noel Ferrier, who has had a June 6-18. See Member Activities (p. 5) "lady". Now a new production by Vic for pre-theatre dinner on Wednesday, toria State Opera, fresh from a most distinguished career in the theatre and successful season in Melbourne, comes in films, will play Alfred P.