A Performance Guide to Arthur Bliss's Sonata for Viola and Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

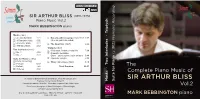

Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) Céleste Series Piano Music Vol.2 MARK BEBBINGTON Piano Riptych

SOMMCD 0148 DDD Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) Céleste Series Piano Music Vol.2 MArK BEBBiNGtON piano riptych t Masks (1924) · 1 A Comedy Mask 1:21 bl Das alte Jahr vergangen ist (1932) 2:57 2 A Romantic Mask 3:50 (The old year has ended) Première Recording 3 A Sinister Mask 2:22 bm The Rout Trot (1927) 2:42 4 A Military Mask 2:53 Triptych (1970) Two Interludes (1925) .1912) bn Meditation: Andante tranquillo 7:08 5 c No. 1 4:09 bo ( Dramatic Recitative: 6 nterludes No. 2 3:23 Grave – poco a poco molto animato 5:48 i bp Suite for Piano (c.1912) Capriccio: allegro 5:09 Première Recording bq wo 7 ‛Bliss’ (One-Step) (1923) 3:15 Prelude 5:47 t The 8 Ballade 7:48 Total Duration: 62:11 · 9 Scherzo 3:32 Complete Piano Music of Recorded at Symphony Hall, Birmingham, 3rd & 4th January 2011 Sir Arthur Bliss Steinway Concert Grand Model 'D' Masks Suite for Piano Recording Producer: Siva Oke Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Vol.2 Front Cover photograph of Mark Bebbington: © Rama Knight Design & Layout: Andrew Giles © & 2015 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND MArK BEBBiNGtON piano Made in the EU THE SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF SIR ARTHUR BLISS Vol. 2 Anyone coming new to Bliss’s piano music via these publications might be forgiven for For anyone who has investigated the piano music of Arthur Bliss, the most puzzling thinking that the composer’s contribution to the repertoire was of little significance, aspect is surely that, as a body of work, it remains so little known. -

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium

2019 Preview Notes • Week Two • Persons Auditorium Saturday, July 20 at 8:00pm Flute Quartet in D Major, K. 285 (1777-78) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Born January 27, 1756 • Died December 5, 1791 Duration: approx. 15 minutes Last Marlboro performance: 2011 When Mozart was just a few years younger than the junior participants in this group, he travelled throughout Europe with his mother in search of employment. While in Mannheim on his way to Paris, he met a Dutch merchant named Willem van Britten Dejong who happened to be an amateur flute player. Dejong, who had made his fortune in India, was happy to commission three concertos and three quartets for his instrument. Mozart, who needed the funds, was happy to accept. However, he only completed the quartets and two concertos (one a transcription of a previously-composed oboe concerto) by the time he left Mannheim. What he did write, though, charmingly showcases the flute. In this quartet, that instrument takes the lead throughout a buoyant Allegro beginning, a delicate Adagio accompanied by sparkling plucking from the strings, and a boisterous but well-balanced Rondo conclusion. Participants: Giorgio Consolati, flute; Hiroko Yajima, violin; Jordan Bak, viola; Alexander Hersh, cello Octet (2004) Jörg Widmann Born June 19, 1973 • In residence 2008, 2019 Duration: approx. 30 minutes Marlboro Premiere Though Widmann’s Octet features frequent microtones, he admits that the piece is “almost throughout, a tonal piece,” which was “risky to write in 2004.” The instrumentation suggests a clear connection to Schubert’s genre-making octet, and the piece’s central third movement, which is titled Lied ohne Worte, is a plangent nod to the composer who wrote so many Lieder over the course of his short life. -

Pembelajaran Praktik Biola Melalui Tiga Buku Karya C

PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL: KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI TESIS Oleh SOPIAN LOREN SINAGA NIM. 117037004 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER (S2) PENCIPTAAN DAN PENGKAJIAN SENI FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2012 Universitas Sumatera Utara PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL: KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI T E S I S Untuk memperoleh gelar Magister Seni (M.Sn.) dalam Program Studi Magister (S-2) Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni pada Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Oleh SOPIAN LOREN SINAGA NIM 117037004 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER (S2) PENCIPTAAN DAN PENGKAJIAN SENI FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2013 Universitas Sumatera Utara Judul Tesis : PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL:KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI Nama : Sopian Loren Sinaga Nomor Pokok : 117037004 Program Studi : Magister (S2) Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni Menyetujui Komisi Pembimbing, Drs. Muhammad Takari, M.Hum., Ph.D. Dra. Heristina Dewi, M.Pd. NIP. 196512211991031001 NIP. 196605271994032010 Ketua Anggota Program Studi Magister (S-2) Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni Dekan, Ketua, Drs. Irwansyah Harahap, M.A. Dr. Syahron Lubis, M.A. NIP 196212211997031001 NIP 195110131976031001 Universitas Sumatera Utara Tanggal lulus: Telah diuji pada Tanggal PANITIA PENGUJI UJIAN TESIS Ketua : Drs. Irwansyah, M.A. (……………………..) Sekretaris : Drs. Torang Naiborhu, M.Hum. (..…..………………..) Anggota I : Drs. -

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 102 Viola V30 N2 Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 1

Viola V30 N2_Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 101 30 Years of JAVS Features: A Survey of Hans Gál’s Chamber Works Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements, Part I Alfred Uhl’s Viola Études Primrose’s Transcriptions Volume 30 Volume Number 2 and Arrangements Journal of Journal the American Viola Society Viola V30 N2_Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 102 Viola V30 N2_Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 1 Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Fall 2014 Volume 30 Number 2 Contents p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President p. 7 News & Notes: Announcements ~ In memoriam Feature Articles p. 13 A Survey of Hans Gál’s Chamber Works with Viola: Richard Marcus writes on the Austrian composer Hans Gál, who emigrated to Great Britain due to World War II. A catalog of his chamber works with viola is provided, along with a look at various selections of these compositions. p. 27 Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part I: In the first installment of a two-part article, Elena Artamonova provides a detailed historical context of the Russian violist Vadim Borisovsky—who, in addition to his musical accomplishments, was also a poet. p. 37 Alfred Uhl’s Viola Études: Studies with a Heart: Études have long been an indispensible part of a violist’s training, but have also been typically confined to providing technical facility. Danny Keasler looks at the études of Alfred Uhl, which include melodic aspects that can relate directly to repertoire. -

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets Of

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) By © 2017 Matthew Butterfield DMA, University of Kansas, 2017 M.M., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011 B.S., The Pennsylvania State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Dr. Colin Roust Dr. Sarah Frisof Dr. Eric Stomberg Dr. Michelle Hayes Date Defended: 2 May 2017 The dissertation committee for Matthew Butterfield certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Date Approved: 10 May 2017 ii Abstract Léon Goossens’s virtuosity, musicality, and developments in playing the oboe expressively earned him a reputation as one of history’s finest oboists. His artistry and tone inspired British composers in the early twentieth century to consider the oboe a viable solo instrument once again. Goossens became a very popular and influential figure among composers, and many works are dedicated to him. His interest in having new music written for oboe and strings led to several prominent pieces, the earliest among them being the oboe quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927). Bax’s music is strongly influenced by German romanticism and the music of Edward Elgar. This led critics to describe his music as old-fashioned and out of touch, as it was not intellectual enough for critics, nor was it aesthetically pleasing to the masses. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

The English Oboe: Rediscovered 4 AEGEUS (1996) 8’21 THOMAS ATTWOOD WALMISLEY (1814-1856) SONATINA NO

EDMUND RUBBRA (1901-1986) SONATA IN C FOR OBOE AND PIANO, OP. 100 1 Con moto 5’49 2 Elegy 4’15 3 Presto 3’30 EDWARD LONGSTAFF (1965- ) The English Oboe: Rediscovered 4 AEGEUS (1996) 8’21 THOMAS ATTWOOD WALMISLEY (1814-1856) SONATINA NO. 1 JAMES TURNBULL oboe 5 Andante mosso - Allegro moderato 8’49 JOHN CASKEN (1949- ) 6 AMETHYST DECEIVER FOR SOLO OBOE (2009) 7’16 (World premiere recording) GUSTAV HOLST (1874-1934) TERZETTO FOR FLUTE, OBOE AND VIOLA 7 Allegretto 6’59 8 Un poco vivace 4’36 MICHAEL BERKELEY (1948- ) THREE MOODS FOR UNACCOMPANIED OBOE 9 Very free. Moderato 5’24 10 Fairly free. Andante 2’33 11 Giocoso 2’13 RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) SIX STUDIES IN ENGLISH FOLKSONG FOR COR ANGLAIS AND PIANO 12 Adagio 1’37 13 Andante sostenuto 1’28 14 Larghetto 1’31 15 Lento 1’36 16 Andante tranquillo 1’33 17 Allegro vivace 0’54 Total playing time: 68’34 James Turnbull ~ oboe / cor anglais (all tracks) Libby Burgess ~ piano (tracks 1-5 and 12-17) Matthew Featherstone ~ flute (tracks 7-8) Dan Shilladay ~ viola (tracks 7-8) FOREWORD PROGRAMME NOTES For a long time, I have been drawn towards English oboe music. It was therefore a Edmund Rubbra wrote much chamber music, including pieces for almost every straightforward decision to choose this repertoire to record. My aim was to introduce the instrument. He composed his Sonata for Oboe and Piano, op. 100, in 1958 for most varied programme possible: as a result, this disc spans over a century. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College.