The New Music Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

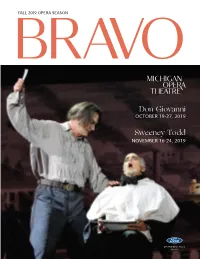

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Darynn Zimmer Is an Active Soprano, Producer, Recording Artist and Educator

Darynn Zimmer is an active soprano, producer, recording artist and educator. She has sung with international and American festivals, orchestras and regional operatic companies: Spoleto (USA & Italy); Orquestra Petrobras, Rio; Aspen Opera Theater; American Music Theater Festival; Cen- ter for Contemporary Opera; American Opera Projects: Encompass New Opera Theater: Greens- boro; Skylight and Tampa, performing contemporary and standard repertoire by Bach, Copland, Anthony Davis, Donizetti, Foss, Glass, Monteverdi, Orff and Somei Satoh, among many others. She has appeared as soprano soloist at Carnegie Hall, Alice Tully Hall, Merkin Concert Hall, and the Morgan Library, and with conductors such as Marin Alsop, Bradley Lubman, Paul Nadler, Anton Coppola, David Randolph, Robert Bass and Richard Westenburg. In recent engagements, Ms. Zimmer performed at the 2016 Bergedorfer Musiktage, the largest summer festival in Hamburg. She was invited to perform the Children’s Songs, Op.13, by Mieczyslaw Weinberg in Chamber Music at the Scarab Club in Detroit, a performance co-spon- sored by Michigan Opera Theater to highlight their production of The Passenger. She per- formed these songs again in Miami, in connection with the production at Florida Grand Opera. As performer and co-producer, Ms. Zimmer was part of ‘Ciao, Philadelphia 2015’ festival in, “Introducing B Cell City,” a multi-media work in progress addressing cancer and the environ- ment. Ms. Zimmer sang ‘Elizabeth Christine,’ in a Center for Contemporary Opera showcase of Scott Wheeler’s opera, The Sorrows of Frederick. She appeared in the world premiere of Zin- nias: The Life of Clementine Hunter by Toshi Reagon and Bernice Johnson Reagon, directed by Robert Wilson. -

COCKEREL Education Guide DRAFT

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide The Golden Cockerel By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 2 The Story ...................................................................................................... 3-4 The Composer ............................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 7 Behind the Scenes Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8-9 The Russian Five .......................................................................................... 10 Satire and Irony ........................................................................................... 11 The Inspiration .............................................................................................. 12-13 Costume Design ........................................................................................... 14 Scenic Design ............................................................................................... 15 Q&A with the Queen of Shemakha ............................................................. 16-17 In The News In The News, 1924 ........................................................................................ 18-19 -

Select – 1Er Número – Museos

EDITORIAL e BIENVENIDOS A UNA NUEVA EXPERIENCIA SELECT Con esta edición inauguramos mucho más que una revista: e aquí nace un lugar de encuentro que te brindará información Juan Carlos Chomali A. y oportunidades únicas, un espacio Country Head donde podrás vivir la experiencia Santander Uruguay de ser un cliente Select. Queremos que disfrutes cada una de nuestras entregas, elaboradas de forma exclusiva. Nos ilusiona ser capaces de sumar valor a tu vida. Veremos dónde convergen la genialidad arquitectónica, el arte, el mundo gourmet y todas aquellas cosas que mueven tus sentidos. Es un gran orgullo que seas nuestro cliente y cada día nos elijas. Tu preferencia nos inspira a seguir avanzando en brindarte el servicio que mereces. EDITORIAL e os expresiones con las que nos codeamos con frecuencia en estos tiempos vertigino- sos, como «el tiempo es el nuevo lujo» o «la vida está hechaD de momentos», nos recuerdan que es necesario hacer una pausa para reencontrarnos con lo que realmente disfrutamos, para llenarnos de más momentos que nos den felicidad. A partir de hoy, The Select Experience Magazine es una invitación a en- contrarnos con los placeres de la vida, a explorar y reconectarnos con nuestros cinco sentidos. Una invitación a llenarnos de vida, gracias a per- sonas, actividades, lugares y experiencias con alma. Será un lugar de encuentro bimestral, en el que proponemos diferentes opciones para que inviertan el tiempo en el arte del saber vivir. El recorrido de la revista se propone como un viaje por diferentes ter- renos: la moda, un estilo de vida saludable, el placer de viajar, la sen- e sibilidad por el arte, el dinamismo de la tecnología, el entretenimiento que nos emociona, los temas de actualidad y las tendencias, que nos permiten entender mejor el presente y el futuro, y las historias de vida de Cecilia Camors personajes fascinantes. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Summer 2014 Boston Symphony Orchestra

boston symphony orchestra summer 2014 Andris Nelsons, Ray and Maria Stata Music Director Designate Bernard Haitink, LaCroix Family Fund Conductor Emeritus, Endowed in Perpetuity Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 133rd season, 2013–2014 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Edmund Kelly, Chair • William F. Achtmeyer, Vice-Chair • Carmine A. Martignetti, Vice-Chair • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chair • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer David Altshuler • George D. Behrakis • Jan Brett • Paul Buttenwieser • Ronald G. Casty • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Diddy Cullinane • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Charles W. Jack, ex-officio • Stephen B. Kay • Joyce Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Robert P. O’Block • Susan W. Paine • Peter Palandjian, ex-officio • John Reed • Carol Reich • Arthur I. Segel • Roger T. Servison • Wendy Shattuck • Caroline Taylor • Roberta S. Weiner • Robert C. Winters Life Trustees Vernon R. Alden • Harlan E. Anderson • David B. Arnold, Jr. • J.P. Barger • Gabriella Beranek • Leo L. Beranek • Deborah Davis Berman • Peter A. Brooke • John F. Cogan, Jr. • Mrs. Edith L. Dabney • Nelson J. Darling, Jr. • Nina L. Doggett • Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick† • Nancy J. Fitzpatrick • Thelma E. Goldberg • Charles H. Jenkins, Jr. • Mrs. Béla T. Kalman • George Krupp • Mrs. Henrietta N. Meyer • Richard P. Morse • David Mugar • Mary S. Newman • Vincent M. O’Reilly • William J. Poorvu • Peter C. Read • Edward I. Rudman • Richard A. Smith • Ray Stata • Thomas G. Stemberg • John Hoyt Stookey • Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. • John L. Thorndike • Stephen R. -

Frauenleben in Magenza

www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Frauenleben in Magenza Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender seit 1991 und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz Frauenleben in Magenza Frauenleben in Magenza Die Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz 3 Frauenleben in Magenza Impressum Herausgeberin: Frauenbüro Landeshauptstadt Mainz Stadthaus Große Bleiche Große Bleiche 46/Löwenhofstraße 1 55116 Mainz Tel. 06131 12-2175 Fax 06131 12-2707 [email protected] www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Konzept, Redaktion, Gestaltung: Eva Weickart, Frauenbüro Namenskürzel der AutorInnen: Reinhard Frenzel (RF) Martina Trojanowski (MT) Eva Weickart (EW) Mechthild Czarnowski (MC) Bildrechte wie angegeben bei den Abbildungen Titelbild: Schülerinnen der Bondi-Schule. Privatbesitz C. Lebrecht Druck: Hausdruckerei 5. überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage Mainz 2021 4 Frauenleben in Magenza Vorwort des Oberbürgermeisters Die Geschichte jüdischen Lebens und Gemein- Erstmals erschienen ist »Frauenleben in Magen- delebens in Mainz reicht weit zurück in das 10. za« aus Anlass der Eröffnung der Neuen Syna- Jahrhundert, sie ist damit auch die Geschichte goge im Jahr 2010. Weitere Auflagen erschienen der jüdischen Frauen dieser Stadt. 2014 und 2015. Doch in vielen historischen Betrachtungen von Magenza, dem jüdischen Mainz, ist nur selten Die Veröffentlichung basiert auf den Porträts die Rede vom Leben und Schicksal jüdischer jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen und auf den Frauen und Mädchen. Texten zu Einrichtungen jüdischer Frauen und Dabei haben sie ebenso wie die Männer zu al- Mädchen, die seit 1991 im Kalender »Blick auf len Zeiten in der Stadt gelebt, sie haben gelernt, Mainzer Frauengeschichte« des Frauenbüros gearbeitet und den Alltag gemeistert. -

REGION I0 - MARINE Seymour Schiff 603 Mead Terrace, South Hempstead NY 11550 Syschiff @ Optonline.Net

REGION I0 - MARINE Seymour Schiff 603 Mead Terrace, South Hempstead NY 11550 syschiff @ optonline.net Alvin Wollin 4 Meadow Lane, Rockville Centre NY 11 570 After a series of unusually warm winters and a warm early December, we went back to the reality of subnormal cold and above normal snow. For the three months, temperatures were, respectively, 1.3"F, 4.6" and 4.5" below normal, with a season low 8" on 16 February. This season's average temperature was 10" below last year. Precipitation was very slightly above normal for December, half of normal for January, fifty percent above normal in February, with half of it in the form of snow. On 7 February, 5" fell. And an additional 19" fell on the 16-17th, for the fourth snowiest month on record. The warm early weather induced an unusual number of birds to stay far into the season and kept some for the entire winter. On the other hand, there were absolutely no northern finches, except for a very few isolated Pine Siskins. On 14 December, a Pacific Loon in basic plumage was found by Tom Burke, Gail Benson and Bob Shriber at Camp Hero on the Montauk CBC. It was subsequently seen there and at the point by others on 24,27 and 28 December. On 28 December, Guy Tudor saw a Greater Shearwater sail in toward Montauk Point before returning out to sea. This is a very late record. A Least Bittern, apparently hit by a car "somewhere in East Hampton" on 25 February, was turned over to a local rehabilitator. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

Kurt Weill Newsletter Protagonist •T• Zar •T• Santa

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 11, Number 1 Spring 1993 IN THI S ISSUE I ssues IN THE GERMAN R ECEPTION OF W EILL 7 Stephen Hinton S PECIAL FEATURE: PROTAGON IST AND Z AR AT SANTA F E 10 Director's Notes by Jonathan Eaton Costume Designs by Robert Perdziola "Der Protagonist: To Be or Not to Be with Der Zar" by Gunther Diehl B OOKS 16 The New Grove Dictionary of Opera Andrew Porter Michael Kater's Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany Susan C. Cook Jilrgen Schebera's Gustav Brecher und die Leipziger Oper 1923-1933 Christopher Hailey PERFORMANCES 19 Britten/Weill Festival in Aldeburgh Patrick O'Connor Seven Deadly Sins at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Paul Young Mahagonny in Karlsruhe Andreas Hauff Knickerbocker Holiday in Evanston. IL bntce d. mcclimg "Nanna's Lied" by the San Francisco Ballet Paul Moor Seven Deadly Sins at the Utah Symphony Bryce Rytting R ECORDINGS 24 Symphonies nos. 1 & 2 on Philips James M. Keller Ofrahs Lieder and other songs on Koch David Hamilton Sieben Stucke aus dem Dreigroschenoper, arr. by Stefan Frenkel on Gallo Pascal Huynh C OLUMNS Letters to the Editor 5 Around the World: A New Beginning in Dessau 6 1993 Grant Awards 4 Above: Georg Kaiser looks down at Weill posing for his picture on the 1928 Leipzig New Publications 15 Opera set for Der Zar /iisst sich pltotographieren, surrounded by the two Angeles: Selected Performances 27 Ilse Koegel 0efl) and Maria Janowska (right). Below: The Czar and His Attendants, costume design for t.he Santa Fe Opera by Robert Perdziola. -

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Vol

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Vol. 3, No. I Spring, 1985 Yale Press To Publish Essays Threepenny Opera at R & H Yale University Press has accepted for publica As of 11 December 1984, Rodgers & Ham tion a coUection of essays on Kurt Weill sched merstein Theatre Library has added The uled for completion in 1985. A New Orpheus: Threej>enny Opera to its catalogue of plays for Essays on Kurt Weill evolved primarily from stock and amateur licensing in the United papers presented at the Kurt Weill Conference States. The American version by Marc Blitz in 1983. It includes a contribution from virtually stein ran for seven years at New York's Theatre every active Weill scholar throughout the world. de Lys in the late Fifties and had been previ AU of the papers have been expanded and ously licensed by Tarns-Witmark Music Library, revised and represent the most extensive criti Inc. cal survey of WeiU's music and career to date. The Rodgers & Hammerstein Theatre The coUection, edited by Kim Kowalke, was Library is preparing new scripts and vocal accepted unanimously by the editorial board of scores which will be consistent with the high this most prestigious of scholarly publishers. quality of their other publications. Jn addition to Among the highlights of the anthology are David Threepenny, R & H also administers stock and Drew's definitive study of Der Kuhhandel, a key amateur rights to Knickerbocker Holiday, Lost in work in WeiU's ouevre that has remained unpub the St,ars, and Street Scene. lished and unperformed since 1935. The book ;,We are thrilled and excited to announce the will attract readers from diverse disciplines, addition of Threepenny to our catalog ," said The since the essays tackle many issues central to odore Chapin, Managing Director of R & H.