51-2대지01shawn Shen.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Pacific

South Pacific Governance in the Pacific: the dismissal of Tuvalu's Governor-General Tauaasa Taafaki BK 338.9 GRACE FILE BARCOOE ECO Research School of Pacific and Asian \\\\~ l\1\1 \ \Ul\\ \ \\IM\\\ \\ CBR000029409 9 Enquiries The Editor, Working Papers Economics Division Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra 0200 Australia Tel (61-6) 249 4700 Fax (61-6) 257 2886 ' . ' The Economics Division encompasses the Department of Economics, the National Centre for Development Studies and the Au.§.tralia-J.apan Research Centre from the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, the Australian National University. Its Working Paper series is intended for prompt distribution of research results. This distribution is preliminary work; work is later published in refereed professional journals or books. The Working Papers include V'{Ork produced by economists outside the Economics Division but completed in cooperation with researchers from the Division or using the facilities of the Division. Papers are subject to an anonymous review process. All papers are the responsibility of the authors, not the Economics Division. conomics Division Working Papers " South Pacific Governance in the Pacific: the dismissal of Tuvalu's Governor-General Tauaasa Taafaki / o:,;7 CJ<,~ \}f ftl1 L\S\\ltlR~ Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies C;j~••• © Economics Division, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, 1996. This work is copyright. Apart from those uses which may be permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 as amended, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. -

Feuille De Style Word 2003 Doctorants

THÈSE PRÉSENTÉE POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE BORDEAUX ÉCOLE DOCTORALE SP2 Science politique Par Damien VALLOT LE RÉCIT CORALLIEN Production, diffusion et cadrage des récits d’action publique de la disparition des États atolliens entre Tuvalu, Kiribati et la Nouvele-Zélande Sous la direction de : Denis Constant MARTIN Soutenue le 15 décembre 2015 Membres du jury : M. SMITH, Andy Directeur de recherche FNSP IEP de Bordeaux Président Mme. DUVAT, Virginie Professeur des Universités Université de La Rochelle Rapporteur M. RADAELLI, Claudio Professeur des Universités University of Exeter Rapporteur Mme KASTORYANO, Riva Directrice de recherche CNRS Sciences Po Paris Examinatrice M. MARTIN, Denis Constant Directeur de recherche FNSP IEP de Bordeaux Directeur Titre : Le récit corallien : production, diffusion et cadrage des récits d’action publique de la disparition des États atolliens entre Tuvalu, Kiribati et la Nouvelle-Zélande. Résumé : Depuis la prise en compte croissante du changement climatique, de nombreux commentateurs ont commencé à raconter une histoire : celle des petits États insulaires du Pacifique sud, entièrement constitués d’atolls, qui risquent de disparaître en raison de l’élévation du niveau marin. Nous considérons que cette histoire est un « récit d’action publique » destiné à attirer l’attention et à convaincre les décideurs politiques d’agir pour empêcher la réalisation du problème ou lui trouver une solution. Ces « récits de la disparition » présentent deux particularités : ils ne sont associés à aucune politique publique déjà mise en œuvre et ils sont mobilisés par des acteurs variés issus des milieux politiques et de la société civile. À partir de la littérature sur l’analyse cognitive des politiques publiques et plus particulièrement l’analyse des récits de politiques publiques, cette thèse se propose d’étudier la production, la diffusion et les cadrages de ces récits de la disparition à l’aide de méthodes mixtes associant une démarche qualitative d’enquête avec la réalisation d’une analyse statistique textuelle. -

Executive Instability in TUVALU & NAURU

By Lisepa Paeniu Outline The issue of instability Parliamentary structures of both countries Options that could be introduced Executive Instability Motions of vote of no confidence in the Head of Government MPs defect from Government to join Opposition Instability includes: Different HoG A change in the Ministerial portfolios of Cabinet, or a new Cabinet altogether or just a new PM/President Tuvalu Year Prime Minister 1978-1981 Toaribi Lauti 1981-89 Tomasi Puapua 1989-92 Bikenibeu Paeniu 1993-96 Kamuta Latasi 1996-99 Bikenibeu Paeniu 1999-2000 Ionatana Ionatana 2000-2001 Faimalaga Luka 2001-2002 Koloa Talake 2002-04 Saufatu Sopoaga 2006-2010 Apisai Ielemia 2010 Maatia Toafa 2010-11 Willy Telavi Why is exec instability an issue? Economy suffers Lack of continuity of policies International obligations Implementation of reforms inconsistent Termination of civil servants Public confidence undermined Political Systems in Tuvalu and Nauru Westminister parliamentary systems Nauru has 18 MPs,Tuvalu has 15 MPs No formal political party system Both have HoG selected by majority in Parliament Speakers are elected as MPs No control/consequence for MPs that cross the floor No limit on when an MP tables a motion of no confidence Options 1. People to vote for PM directly (Kiribati Constitution) Section 32 of the Constitution 1979 – 1991 H.E Ieremia Tabai, GCMG (Nonouti) 1991-1994 H.E Teatao Teannaki (Abaiang) 1994-2002 H.E Teburoro Tito (South Tarawa) 2003- current H.E Anote Tong (Maiana) 2. The office of the Speaker filled by a non-elected MP (Niue Constitution) Options 2 3. MP who crosses floor to resign from Parliament and a by- election to be held (Electoral Act 1967 Samoa) 4. -

Who Is Who 1997

2nd Volume Convention on Climate Change Who is Who in the UNFCCC Process 1996 - 1997 FCCC Directory of Participants at Meetings of the Convention Bodies in the period July 1996 to December 1997 UN (COP2 - COP3) Contents Introduction page 3 Representatives of Countries page 5 Representatives of Observer Organizations page 259 Appendix I - Intergovernmental organizations accredited by the Conference of the Parties up to its third session page 482 Appendix II - Non-governmental organizations accredited by the Conference of the Parties up to its third session page 483 Appendix III - Alphabetical index of entries page 486 Appendix IV - Information update form page 523 1 2 Introduction This is the second volume of the Who’s Who in the UNFCCC Process. As indicated by its subtitle, this CC:INFO product is a directory of delegates and observers having attended the second or third sessions of the Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or any of its subsidiary body meetings in between (COP2-COP3). This Who is Who was developed to provide those involved in the Climate Change process with a single, easy-to-use document, enabling them to renew or establish contact with each other. The Who is Who provides the title and contact information (e.g., institutional and e-mail addresses, direct telephone and fax numbers, etc…) for each individual, as provided to the secretariat during conference registration. Some of this information is now no longer valid, due to, e.g., new professional reassignments, including in some cases to the Climate Change Secretariat. -

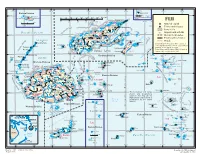

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

Buca Bay, Taveuni, Fiji. We Were up at 3:30 Am to Catch a Plane to the Northern Tip of Taveuni, Fiji’S Third Largest Island, Just East of Vanua Levu

July 21: Buca Bay, Taveuni, Fiji. We were up at 3:30 am to catch a plane to the northern tip of Taveuni, Fiji’s third largest island, just east of Vanua Levu. The plane was a fourteen seater and flew low allowing a good view of the coral reefs between islands. There are a great many reefs that would not be visible any other way. They are beautiful to see, surrounded by the dark blue, deep waters, and seen in lighter blues and azure. Once Lynn got used to the plane she took many pictures of the reefs below. We met a couple from Australia who were headed for the same ship we were. The four of us got there earlier than the rest and had nearly an extra half day of adventure. A short van ride from the airport got us to the cruise ship Tui Tai. This is a small ship with 12 cabins and during our stay there were at most 13 passengers. Lynn and I were in one of two staterooms on the upper deck. It was cramped and we appreciated the extra space in the the two grand staterooms. This ship likes to cruise the Northeastern part of Fiji that is more remote from civilization. A short cruise took us to a site from which we bicycled to the International Date Line. We could hop from Sunday to Monday and back again. I could not discern any real difference. Then we snorkeled in a beautiful reef (“the farm”) of mixed soft and hard corals. -

Filling the Gaps: Identifying Candidate Sites to Expand Fiji's National Protected Area Network

Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20-21 September 2010 Stacy Jupiter1, Kasaqa Tora2, Morena Mills3, Rebecca Weeks1,3, Vanessa Adams3, Ingrid Qauqau1, Alumeci Nakeke4, Thomas Tui4, Yashika Nand1, Naushad Yakub1 1 Wildlife Conservation Society Fiji Country Program 2 National Trust of Fiji 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University 4 SeaWeb Asia-Pacific Program This work was supported by an Early Action Grant to the national Protected Area Committee from UNDP‐GEF and a grant to the Wildlife Conservation Society from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (#10‐94985‐000‐GSS) © 2011 Wildlife Conservation Society This document to be cited as: Jupiter S, Tora K, Mills M, Weeks R, Adams V, Qauqau I, Nakeke A, Tui T, Nand Y, Yakub N (2011) Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network. Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20‐21 September 2010. Wildlife Conservation Society, Suva, Fiji, 65 pp. Executive Summary The Fiji national Protected Area Committee (PAC) was established in 2008 under section 8(2) of Fiji's Environment Management Act 2005 in order to advance Fiji's commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)'s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA). To date, the PAC has: established national targets for conservation and management; collated existing and new data on species and habitats; identified current protected area boundaries; and determined how much of Fiji's biodiversity is currently protected through terrestrial and marine gap analyses. -

Contemporary Pacific Vol. 24, No. 1 (2012) Page 67 of Katerina

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa ERRATA Contemporary Pacific Vol. 24, No. 1 (2012) Page 67 of Katerina Teaiwa’s article on “Choreographing Difference: The (Body) Politics of Banaban Dance,” in The Contemporary Pacific 24:1 erroneously included mention of Tuvalu with regard to reserve funds from phosphate mining. The last two sentences of paragraph 3 should read as follows: “Reserve funds, generated from the income from the extraction and ship- ping of twenty million tons of phosphate under British colonial administra- tion, served as a giant savings account with which to launch the independent state of Kiribati (see Williams and Macdonald 1985 and Van Trease 1993). This account is now worth hundreds of millions of dollars and is earning interest in banks around the globe.” Choreographing Difference: The (Body) Politics of Banaban Dance Katerina Martina Teaiwa In London, during the protracted court case involving Ban- aban compensation claims for the destruction of their Ocean Island homeland by phosphate mining, a daily newspaper posed the question: “Who are these Banaban people any- way?” A group of Banaban dancers were in London at the time and they responded to the question. They announced a performance of music and dance with the simple and power- ful statement: “We, the Banabans, are the people who dance like this. ” Jennifer Shennan, “Approaches to the Study of Dance in Oceania” This article represents aspects of research conducted between 1999 and 2002 in Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, and Kiribati, and during two brief trips to Rabi Island in 2007–2008. -

Vanua Levu Vita Levu Suva

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 0 10 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Coral reefs Sasa Nasea l Cobia e n n Airports and airfields Pacific Ocean Navidamu Rabi a Labasa e y Nailou h v a C 16° 30’ Natua ro B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld ka o Nabiti Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu Bua conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua a parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. s Yandua Nadivakarua Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Nanuku Passage Viwa Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata tu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Wayalevu Malake - Vanua Balavu I- Nasau N r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna C H Kuata Tavua Vaileka h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Ra n Mago N Sorokoba n Lomaiviti -

Cruising the Fiji Islands

The Fiji Islands Cruising in Fiji waters offers many of those once-in-a-lifetime moments. You may experience remote and uninhabited islands, stretching reefs, exhilarating diving, plentiful fishing, a range of cultural experiences and you will still leave wishing to cruise further and explore more…just to the next island…and the island after that….. There are so many reasons to cruise the idyllic waters of Fiji. It is one of the warmest, friendliest nations on earth and caters to cruisers looking for adventure, time out, experiences with locals, and isolated cruising. Fiji is a nation comprising 322 islands in 18,376 square kilometers of the Pacific Ocean. The islands range from being large and volcanic with high peaks and lush terrain, to atolls so small they peak out of the warm aqua water only when the tide recedes. The islands range from being large and volcanic with high peaks and lush terrain to atolls so small they peak out of the warm aqua water when the tide recedes. 2 Yacht Partners Fiji – Super Yacht Support Specialists www.yachtpartnersfiji.com Yasawa & Mamanuca Islands White sand beaches and protected cruising The Yasawa and Mamanuca Islands are the closest cruising ground to the international airport. A departure from Port Denarau (which is only 20 minutes from Nadi international airport) will see you at Malolo Island, the southern-most in the Yasawa/Mamanuca chain of islands, in a couple of hours. This chain of islands and reefs is strung out over 80 nautical miles from Malolo to Yasawa-I-Ra-ra. Most of the traveling is inside of the reefs with short passages between many good anchorages and fine beaches. -

Fiji Islands

i ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK TA: 6039-REG REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS: COUNTRY ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS Mainstreaming Environmental Considerations in Economic and Development Planning Processes (FINAL DRAFT) Prepared by: James T. Berdach February 2005 The views expressed in this document are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent positions of the Asian Development Bank or the Government of the Republic of the Fiji Islands. ii CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 November 2004) Currency Unit – Fiji Dollars (FJD) FJD 1.00 = $0.5955 $1.00 = FJD 1.6793 ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADTA – advisory technical assistance ALTA – Agricultural Landlord Tenant Act BOD – biochemical oxygen demand CDM – Clean Development Mechanism CEA – Country Environmental Analysis CHARM – Comprehensive Hazard and Risk Management CLIMAP – Climate Change Adaptation Program for the Pacific CSP – Country Strategy and Program CSPU – Country Strategy and Program Update DOE – Department of Environment DPP – Director of Public Prosecution DRRF – Disaster Relief and Rehabilitation Fund EEZ – Exclusive Economic Zone EIA – environmental impact assessment EMB – Environment Management Bill EU – European Union FBSAP – Fiji Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan FEA – Fiji Energy Authority FEU – Forestry Economics Unit FIMSA – Fiji Islands Marine Safety Administration FLMMA – Fiji Locally Managed Marine Area FRUP – Fiji Road Upgrading Project FSC – Fiji Sugar Corporation GDP – gross domestic product GEF – Global Environment Facility GHG – greenhouse -

Tuvalu#.Vff8wxi8ora.Cleanprint

https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2015/tuvalu#.VfF8WXI8ORA.cleanprint Tuvalu freedomhouse.org In March 2014, Sir Kamuta Latasi, the parliamentary speaker, was ousted and replaced by former speaker Otinielu Tauteleimalae Tausi. Tuvalu remains threatened by global climate change and rising sea levels, as well as a sharp reduction in its fresh water supply as a result of low levels of rainfall in recent years. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: Political Rights: 37 / 40 [Key] A. Electoral Process: 12 /12 A governor general represents the British monarch as head of state. The prime minister, chosen by Parliament, leads the government. The unicameral, 15-member Parliament is elected to four-year terms. A six-person council administers each of Tuvalu’s nine atolls. Council members are chosen by universal suffrage for four-year terms. Twenty-six candidates competed in the September 2010 general elections, and Maatia Toafa was elected prime minister. Toafa was ousted in a no-confidence vote in December 2010, after which Willy Telavi replaced him as prime minister. Telavi himself was ousted by a vote of no-confidence in 2013, and Parliament subsequently chose Enele Sopoaga to serve as prime minister. With a two-thirds majority vote in March 2014, legislators removed Sir Kamuta Latasi from the position of parliamentary speaker. Latasi and Sopoaga had clashed in 2013 after Latasi adjourned Parliament before the opposition, at the time led by Sopoaga, could debate the no-confidence motion against Telavi. Former speaker Otinielu Tauteleimalae Tausi replaced Latasi. B. Political Pluralism and Participation: 15 / 16 There are no formal political parties, though no law bars their formation.