Media's Construction of Irish Musical Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unity in Diversity, Volume 2

Unity in Diversity, Volume 2 Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Edited by Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Edited by Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Sabine Asmus, Barbara Braid and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5700-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5700-0 CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................. vii Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept of Unity in Diversity Sabine Asmus Part I: Cultural Markers Chapter One ................................................................................................ 3 Questions of Identity in Contemporary Ireland and Spain Cormac Anderson Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 27 Scottish Whisky Revisited Uwe Zagratzki Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 39 Welsh -

Communication No. 37

THE LIVING TRADITION CEARNÓG BELGRAVE, BAILE NA MANACH, CO. ÁTHA CLIATH Phone: 01-2800295. Fax: 01-2803759 Email:[email protected] Website:http://www.comhaltas.ie COMHALTAS – CORONAVIRUS Communication No. 37 The dictionary definition of ‘Think-Tank’ is ‘a group of people expert in some field, regarded as a source of ideas and solutions to problems’. Never was this more appropriate than on the 19th June. Here we had the leadership of our cultural movement bringing their experience and vision to the table. The Comhaltas Think-Tank na nGael didn’t disappoint. It was focused, positive and energising. The combined experience and responses to challenges was a lighthouse in these troubled times. Well done to all concerned. • FLEADHFEST ‘ A BRILLIANT IDEA’…. It is nostalgic, uplifting and inspirational. Here is how Comhaltas stalwart Joannie O’ Leary of San Francisco Comhaltas puts it: ‘I cannot tell you how excited we are at the release of the FLEADHFEST videos for our West Region this week. We sincerely appreciate the opportunity to present our story, which was greatly enhanced by our West Region Vice-Chair Mary Carey and her daughter Diana in Oregon…What a brilliant idea which has enticed us to start our own branch archives. Congratulations on a wonderfully successful project and thank you.’ • SCOIL ÉIGSE…Briseann an dúchas…. We are delighted to announce that this year the Comhaltas Scoil Éigse will be delivered online via Zoom from Monday August 2nd to Thursday August 5th. The Director again is Kieran Hanrahan and Administrator Liza O'Shea. We were accepting online applications only from 10am, Monday 5th July. -

Savannah Scottish Games & Highland Gathering

47th ANNUAL CHARLESTON SCOTTISH GAMES-USSE-0424 November 2, 2019 Boone Hall Plantation, Mount Pleasant, SC Judge: Fiona Connell Piper: Josh Adams 1. Highland Dance Competition will conform to SOBHD standards. The adjudicator’s decision is final. 2. Pre-Premier will be divided according to entries received. Medals and trophies will be awarded. Medals only in Primary. 3. Premier age groups will be divided according to entries received. Cash prizes will be awarded as follows: Group 1 Awards 1st $25.00, 2nd $15.00, 3rd $10.00, 4th $5.00 Group 2 Awards 1st $30.00, 2nd $20.00, 3rd $15.00, 4th $8.00 Group 3 Awards 1st $50.00, 2nd $40.00, 3rd $30.00, 4th $15.00 4. Trophies will be awarded in each group. Most Promising Beginner and Most Promising Novice 5. Dancer of the Day: 4 step Fling will be danced by Premier dancer who placed 1st in any dance. Primary, Beginner and Novice Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 9:00 AM- Competition to begin at 9:30 AM Beginner Steps Novice Steps Primary Steps 1. Highland Fling 4 5. Highland Fling 4 9. 16 Pas de Basque 2. Sword Dance 2&1 6. Sword Dance 2&1 10. 6 Pas de Basque & 4 High Cuts 3. Seann Triubhas 3&1 7. Seann Triubhas 3&1 11. Highland Fling 4 4. 1/2 Tulloch 8. 1/2 Tulloch 12. Sword Dance 2&1 Intermediate and Premier Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 12:30 PM- Competition to begin at 1:00 PM Intermediate Premier 15 Jig 3&1 20 Hornpipe 4 16 Hornpipe 4 21 Jig 3&1 17 Highland Fling 4 22. -

The Frothy Band at Imminent Brewery, Northfield Minnesota on April 7Th, 7- 10 Pm

April Irish Music & 2018 Márt Dance Association Márta The mission of the Irish Music and Dance Association is to support and promote Irish music, dance, and other cultural traditions to insure their continuation. Inside this issue: IMDA Recognizes Dancers 2 Educational Grants Available Thanks You 6 For Irish Music and Dance Students Open Mic Night 7 The Irish Music and Dance Association (IMDA) would like to lend a hand to students of Irish music, dance or cultural pursuits. We’re looking for students who have already made a significant commitment to their studies, and who could use some help to get to the next level. It may be that students are ready to improve their skills (like fiddler and teacher Mary Vanorny who used her grant to study Sligo-style fiddling with Brian Conway at the Portal Irish Music Week) or it may be a student who wants to attend a special class (like Irish dancer Annie Wier who traveled to Boston for the Riverdance Academy). These are examples of great reasons to apply for an IMDA Educational Grant – as these students did in 2017. 2018 will be the twelfth year of this program, with help extended to 43 musicians, dancers, language students and artists over the years. The applicant may use the grant in any way that furthers his or her study – help with the purchase of an instrument, tuition to a workshop or class, travel expenses – the options are endless. Previous grant recipients have included musicians, dancers, Irish language students and a costume designer, but the program is open to students of other traditional Irish arts as well. -

Reel of the 51St Division

Published by the LONDON BRANCH of the ROYAL SCOTTISH COUNTRY DANCE SOCIETY www. rscdslondon.org.uk Registered Charity number 1067690 Dancing is FUN! No 260 MAY to AUGUST 2007 ANNUAL GENERAL SUMMER PICNIC DANCE MEETING In the Grounds of Harrow School The AGM of the Royal Scottish Country Saturday 30 June 2007 from 2.00-6.00pm. Dancing to David Hall and his Band Dance Society London Branch will be held at The nearest underground station is Harrow on the Hill. St Columba's Church (Upper Hall), Pont Programme Harrow School is 10 to 15 minutes walk east along Street, London, SWI on Friday 15 June 2007. The Dashing White Sergeant .............. 2/2 Lowlands Road (A404) and then right into Peterborough Tea will be served at 6pm and the meeting will The Happy Meeting ......................... 29/9 Road to Garlands Lane, first on left. The 258 bus from commence at 7pm. There will be dancing after Monymusk ...................................... 11/2 Harrow on the Hill tube station heading towards South the meeting. The White Cockade ......................... 5/11 Harrow drops passengers just below Garlands Lane – it’s AGENDA Neidpath Castle ............................... 22/9 about a 5 min ride. The same bus travels from South 1 Apologies. The Wild Geese .............................. 24/3 Harrow tube station also past Garlands Lane. (Note that 2 Approval of minutes of the 2006 AGM. The Reel of the 51st Division ....... 13/10 the fare is £2 now for any length of journey.) Taxis are 3 Business arising from the minutes. The Braes of Breadalbane ................ 21/7 available from the station. Ample car parking is available 4 Report on year's working of the Branch. -

Northwest Accordion News

NORTHWEST ACCORDION NEWS Alpenfest! Holiday Polka Washington State Fair Bringing Structure to Abstract Chaos Accordion Social Reports from the Northwest Groups VOL. 23 NO. 4 Northwest Accordion Society Winter Quarter 2013 Northwest Accordion News NWAS News Deadlines NORTHWEST ACCORDION SOCIETY February 1, May 1, August 1, November 1 The Northwest Accordion News is a quarterly newsletter published by the Northwest Accordion Inquiries, questions, suggestions, etc. Society for and by its members. The purpose of Contact Doris Osgood, 3224 B St., the NWAS News is to unite the membership by Forest Grove, OR 97116. (503) 357-0417. providing news of its members, and articles that E-mail: [email protected] instruct, encourage, and promote the playing of the accordion. NWAS PUBLICATION PRIORITIES ♦ Advertising Mail letters & articles to: ♦ Original Compositions Northwest Accordion Society ♦ News from Our Members 5102 NE 121st Ave. #12, ♦ Instructive/Technical Articles Vancouver, WA 98682 ♦ Summaries from Regional Socials and Or e-mail to: [email protected] Events ♦ Coming Events ADVERTISING Articles will be printed if received prior to Full page $110.00 the publishing deadline. Should space be an Half page $55.00 issue, articles will be printed in the order in which Quarter $30.00 they are submitted. All decisions regarding Business card $10.00 publication will be made by the editors of the Prices are PER ISSUE. US Funds NWAS News. To submit articles for publication, mail Photo-ready Advertising (with accompanying check) them to the Vancouver, WA address listed. It is for this publication may be sent to: preferred that articles be submitted via e-mail as Northwest Accordion Society attached WORD documents or on a disc. -

2014–2015 Season Sponsors

2014–2015 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2014–2015 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following current CCPA Associates donors who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue where patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. MARQUEE Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Diana and Rick Needham Eleanor and David St. Clair Mr. and Mrs. Curtis R. Eakin A.J. Neiman Judy and Robert Fisher Wendy and Mike Nelson Sharon Kei Frank Jill and Michael Nishida ENCORE Eugenie Gargiulo Margene and Chuck Norton The Gettys Family Gayle Garrity In Memory of Michael Garrity Ann and Clarence Ohara Art Segal In Memory Of Marilynn Segal Franz Gerich Bonnie Jo Panagos Triangle Distributing Company Margarita and Robert Gomez Minna and Frank Patterson Yamaha Corporation of America Raejean C. Goodrich Carl B. Pearlston Beryl and Graham Gosling Marilyn and Jim Peters HEADLINER Timothy Gower Gwen and Gerry Pruitt Nancy and Nick Baker Alvena and Richard Graham Mr. -

Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using Folk Dance in Secondary Schools

Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using folk dance in secondary schools By Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Scourfield Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part The Full English The Full English was a unique nationwide project unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage by making over 58,000 original source documents from 12 major folk collectors available to the world via a ground-breaking nationwide digital archive and learning project. The project was led by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and in partnership with other cultural partners across England. The Full English digital archive (www.vwml.org) continues to provide access to thousands of records detailing traditional folk songs, music, dances, customs and traditions that were collected from across the country. Some of these are known widely, others have lain dormant in notebooks and files within archives for decades. The Full English learning programme worked across the country in 19 different schools including primary, secondary and special educational needs settings. It also worked with a range of cultural partners across England, organising community, family and adult learning events. Supported by the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Folk Music Fund and The Folklore Society. Produced by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), June 2014 Written by: Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield Edited by: Frances Watt Copyright © English Folk Dance and Song Society, Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield, 2014 Permission is granted to make copies of this material for non-commercial educational purposes. -

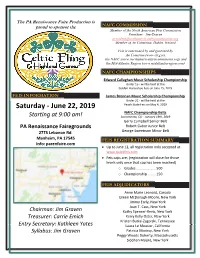

June 22, 2019

The PA Renaissance Faire Production is proud to sponsor the NAFC COMMISSION Member of the North American Feis Commission President: Jim Graven [email protected] Member of An Coimisiun, Dublin, Ireland Feis is sanctioned by and governed by An Comisiun (www.clrg.ie), the NAFC (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) and the Mid-Atlantic Region (www.midatlanticregion.com) NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS Edward Callaghan Music Scholarship Championship Under 15 - will be held at the Golden Horseshoe Feis on June 15, 2019 FEIS INFORMATION James Brennan Music Scholarship Championship Under 21 - will be held at the Peach State Feis on May 4, 2019 Saturday - June 22, 2019 NAFC Championship Belts Starting at 9:00 am! Sacramento, CA - January 19th, 2019 Gerry Campbell Senior Belt PA Renaissance Fairegrounds Robert Gabor Junior Belt 2775 Lebanon Rd. George Sweetnam Minor Belt Manheim, PA 17545 FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY Info: parenfaire.com Up to June 12, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades ..................... 500 o Championship ......... 150 FEIS ADJUDICATORS Anne Marie Leonard, Canada Eileen McDonagh-Moore, New York Jimmy Early, New York Joan T. Cass, New York Chairman: Jim Graven Kathy Spencer-Revis, New York Treasurer: Carrie Emich Kerry Kelly Oster, New York Kristen Butke-Zagorski, Tennessee Entry Secretary: Kathleen Yates Laura Le Meusier, California Syllabus: Jim Graven Patricia Morissy, New York Peggy Woods Doherty, Massachusetts Siobhan Moore, New York COMPETITION FEES CELTIC FLING FEIS FESTIVAL Feis Admission includes ONE day ticket to the festival Competition Fees FEES (you can purchase a second day ticket at registration) Solo Dancing / TR / Sets / Non-Dance Kick-off concert on Friday featuring great performers! $ 10 Bring your appetite and enjoy delicious foods and (per competitor and per dance) refreshing wines, ales & ciders while listening to the live Preliminary Championship music! Gates open at 4PM. -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

THE JOHN BYRNE BAND the John Byrne Band Is Led by Dublin Native and Philadelphia-Based John Byrne

THE JOHN BYRNE BAND The John Byrne Band is led by Dublin native and Philadelphia-based John Byrne. Their debut album, After the Wake, was released to critical acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic in 2011. With influences ranging from Tom Waits to Planxty, John’s songwriting honors and expands upon the musical and lyrical traditions of his native and adopted homes. John and the band followed up After the Wake in early 2013 with an album of Celtic and American traditional tunes. The album, Celtic/Folk, pushed the band on to the FolkDJ Charts, reaching number 36 in May 2015. Their third release, another collection of John Byrne originals, entitled “The Immigrant and the Orphan”, was released in Sept 2015. The album, once again, draws heavily on John’s love of Americana and Celtic Folk music and with the support of DJs around the country entered the FolkDJ Charts at number 40. Critics have called it “..a powerful, deeply moving work that will stay with you long after you have heard it” (Michael Tearson-Sing Out); “The Vibe of it (The Immigrant and the Orphan) is, at once, as rough as rock and as elegant as a calm ocean..each song on this album carries an honesty, integrity and quiet passion that will draw you into its world for years to come” (Terry Roland – No Depression); “If any element of Celtic, Americana or Indie-Folk is your thing, then this album is an absolute yes” (Beehive Candy); “It’s a gorgeous, nostalgic record filled with themes of loss, hope, history and lost loves; everything that tugs at your soul and spills your blood and guts…The Immigrant and the Orphan scorches the earth and emerges tough as nails” (Jane Roser – That Music Mag) The album was released to a sold-out crowd at the storied World Café Live in Philadelphia and 2 weeks later to a sold-out crowd at the Mercantile in Dublin, Ireland. -

Dònal Lunny & Andy Irvine

Dònal Lunny & Andy Irvine Remember Planxty Contact scène Naïade Productions www.naiadeproductions.com 1 [email protected] / +33 (0)2 99 85 44 04 / +33 (0)6 23 11 39 11 Biographie Icônes de la musique irlandaise des années 70, Dònal Lunny et Andy Irvine proposent un hommage au groupe Planxty, véritable référence de la musique folk irlandaise connue du grand public. Producteurs, managers, leaders de groupes d’anthologie de la musique irlandaise comme Sweeney’s Men , Planxty, The Bothy Band, Mozaik, LAPD et récemment Usher’s Island, Dònal Lunny et Andy Irvine ont développé à travers les années un style musical unique qui a rendue populaire la musique irlandaise traditionnelle. Andy Irvine est un musicien traditionnel irlandais chanteur et multi-instrumentiste (mandoline, bouzouki, mandole, harmonica et vielle à roue). Il est également l’un des fondateurs de Planxty. Après un voyage dans les Balkans, dans les années 70 il assemble différentes influences musicales qui auront un impact majeur sur la musique irlandaise contemporaine. Dònal Lunny est un musicien traditionnel irlandais, guitariste, bouzoukiste et joueur de bodhrán. Depuis plus de quarante ans, il est à l’avant-garde de la renaissance de la musique traditionnelle irlandaise. Depuis les années 80, il diversifie sa palette d’instruments en apprenant le clavier, la mandoline et devient producteur de musique, l’amenant à travailler avec entre autres Paul Brady, Rod Stewart, Indigo Girls, Sinéad O’Connor, Clannad et Baaba Maal. Contact scène Naïade Productions www.naiadeproductions.com [email protected] / +33 (0)2 99 85 44 04 / +33 (0)6 23 11 39 11 2 Line Up Andy Irvine : voix, mandoline, harmonica Dònal Lunny : voix, bouzouki, bodhran Paddy Glackin : fiddle Discographie Andy Irvine - 70th Birthday Planxty - A retrospective Concert at Vicar St.