Urban Space and Paradoxical Power in Katherena Vermette's North End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Wordfest Authors – the List

2016 Wordfest authors – The List Meeting an actual person who wrote an Rencontrer LA personne qui a écrit un livre -en actual book -especially one that students particulier celui que les élèves ont lu et apprécié- have read and enjoyed- is a rare, captivating est une expérience relativement rare, captivante and transformative experience. Wordfest et précieuse. Wordfest et le Festival des mots Youth supplies authors from across Canada rassemblent des auteurs et illustrateurs du and around the world to present fun, inspiring Canada du monde entier pour favoriser ces in- and out-of-school events that promote a rencontres entre élèves et auteurs lors love of reading and a deeper appreciation of d’événements en théâtre et en école qui the written word. favorisent un amour de la lecture et une appréciation plus profonde de la littérature. Looking for a book of interest for your Vous cherchez un livre intéressant pour vos students? Look no further! The reading list élèves ? Ne cherchez plus! La liste de livres ci- below, organized by grade level, regroup all dessous, organisée par niveau scolaire, the artists available to visit your school1, from regroupe tous les artistes souhaitant visiter votre Kindergarten to Grade 12. école, de la maternelle à la 12e année. Contact Wordfest to discuss your needs and Contactez Wordfest pour discuter de vos the artist you’d like to meet; depending on besoins et de l'artiste que vous souhaitez their availability, we will definitely work with rencontrer; en fonction de leur disponibilité1, you to create an event that will inspire your nous travaillons avec vous pour créer un students. -

Download This Free Resource At: Includes the 80-Page Guidebook

#69 | Fall/Winter 2016 http://ambp.ca/pbn/ FREE The accidental plus: New work from David Bergen inside publisher Prairie books for kids page 24 & young adults A feature on As well as fiction, drama, A novel from poetry, & non-fiction strong women gg winner Katherena … and much more! Vermette page 26 page 28 Publications Mail Agreement Number 40023290 Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Association of Manitoba Book Publishers 404–100 Arthur Street, Winnipeg, MB R3B 1H3 Escape into a good book this winter C.S. Reardon Cora Siré Judith Alguire Endre Farkas 978-1927426-92-0 978-1927426-89-0 $19.95 $19.95 978-1927426-95-1 978-1927426-86-9 $16.95 $19.95 www.signature-editions.com Reckoning Social Studies Tara Beagan & Andy Moro Trish Cooper 978-1927922-26-2, $15.95 978-1927922-27-9, $15.95 If Truth Be Told True Beverley Cooper Rosa Labordé 978-1927922-28-6, $15.95 978-1927922-25-5, $15.95 FALL 2016 www.jgshillingford.com REPRESENTED BY THE CANADIAN MANDA GROUP • DISTRIBUTED BY UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS With Love and Keeper a Major Organ Tanisha Taitt Julia Lederer 978-1927922-20-0, $15.95 978-1927922-22-4, $15.95 Vitals Liberation Days Rosamund Small David van Belle 978-1927922-24-8, $15.95 978-1927922-21-7, $15.95 #69 FALL/WINTER TOC 2016 NON- FICTION 7 Sacred FICTION 17 Feminine Love Beyond Space & Time 42 YOUNG ADULT & CHILDREN What Matters OUR FEATURED PUBLISHER 7 Love Beyond Space & Time: DRAMA Sci-fi anthology gives voices to 24 The accidental publisher: 33 I Am For You: Stage fighting Indigenous LGBT writers Your Nickel’s Worth -

2019 Annual Report

CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD CHAIR 4 PUBLIC ART 6 GRANTS PROGRAMMING 18 THE MAYOR’S LUNCHEON FOR THE ARTS & the Winnipeg Arts Council Awards 22 INDIGENOUS ARTS LEADERS FELLOWSHIP 26 DECADE IN REVIEW 27 WINNIPEG’S POET LAUREATE 35 ARTS DEVELOPMENT 36 CAROL SHIELDS WINNIPEG BOOK AWARD 38 THANKS 40 GRANTS AWARDED 41 AUDITOR’S REPORT & STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 48 MANDATE, MISSION, VISION & VALUES 59 STAFF, BOARD & ASSESSORS 60 COVER: Bloody Saturday by Bernie Miller ©2020 WINNIPEG ARTS COUNCIL and Noam Gonick. Photo by Liz Tran. PRINTED IN CANADA BY KROMAR PRINTING LTD INSIDE COVERS: Bokeh by Takashi Iwasaki DESIGN BY MIKE CARROLL and Nadi Design. Photo by Anna Mawdsley. MESSAGEFROMTHE EXECUTIVEDIRECTOR he end of a decade can prompt a glance back at memorable mo- ments over ten years. Although this is the 2019 Annual Report and Tincludes a comprehensive account of the year just concluded, the Decade in Review section skims the recent past for occasions worth celebrating. After all, the decade did begin with Winnipeg as Cultural Capital of Canada, and that award alone initiated mo- mentum for the Winnipeg Arts Council that still survives. Although 2019 provided somewhat of a roll- er-coaster ride, the business of the Winnipeg Arts Council ticked on, seeing to grants dis- tribution, expanding the digital application process, continuing to support and invest in Winnipeg’s artistic life. However, there were exceptions that should be recognized. Winnipeg’s first Poet Laureate, Di Brandt, concluded her two-year appointment. Over the two years, she created events, addressed City Council and, of course, wrote poems that enlightened and enlivened the city. -

Teaching Indigenous Literatures

Teaching Indigenous Literatures “Indigenous literatures have dramatically changed the literary, cultural, and theoretical landscape of English studies in Canada” – Emma LaRocque (Cree-Métis) Thanks to the prodigious output and brilliant creativity of Indigenous writers and scholars, there has been increased academic attention to, and interest in, Indigenous literary works . Indigenous artists not only have garnered much attention through major Canadian literary awards, they also have been at the forefront of literary innovation. For scholars less familiar with Indigenous literatures, these works offer an exciting new foray into literary study.. The experience, however, can also be challenging, especially for non-Indigenous scholars who aspire to engage with, and to teach, Indigenous literature in a culturally-sensitive manner. For those who aspire toward such an ethical approach, this list is an excellent starting point. Though far from exhaustive, it provides an overview of Indigenous writings from Turtle Island (North America), thus acting as a gateway into the complex network of Indigenous literatures in its various styles, genres, and subject-matters. In addition to well-known works, new works from emerging Indigenous writers are also identified. This annotated bibliography thus attempts to offer a diverse glimpse of the historic, thematic, and cultural breadth of Indigenous literatures emerging from centuries-long traditions of story, song, and performance – something representative of hundreds of different nations and tribes on Turtle Island. Since it is impossible to name works from all of these multinational voices, this list aspires merely to identify a broad range of writers from various Indigenous nations, albeit with a strong local focus on Anishinaabe, Cree, and Métis authors, upon whose territories and homelands the University of Manitoba is located. -

The Break Katherena Vermette

The Break Katherena Vermette Discussion Questions 1. The book begins with a shocking act of violence and its investigation by the police. In what way does The Break follow the pattern of a more conventional crime or mystery novel, and it what ways does it depart from the forms of these genres? 2. The book is organized into four parts, and at the start of each is a short reflection by an unnamed character. How does this point of view provide insight into the events unfolding in the novel? 3. At the book’s opening Stella is isolated in her home alone with her young children and partly estranged from her family. Why is she distant from her relatives? How do the events of the novel force her to reconsider this distance? 4. When we are introduced to Cheryl, she is trying to revive a series of paintings in which she represents her family members as wolf women (47) and at the end of the novel, Cheryl imagines herself and her sisters to- gether, “just wolves with shed skin” (344). What is the intent of these paintings and what does this image re- flect for Cheryl? Why does she initially have trouble finding the spark of inspiration for these works? 5. The image of the Manitoba Hydro towers recurs throughout the novel. When snow falls on the lines, they buzz constantly, “like a whisper you know is a voice but you can’t hear the words” (5). What disparate places do these towers connect? What might they symbolize? 6. The book’s epigraph comes from Alice Walker: “The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don’t have any.” How would you relate this quote to the relative social power — or powerlessness — of the characters in The Break? Do they think that they have power? Why or why not? 7. -

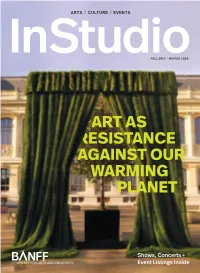

2019 Fall/Winter Instudio

ARTS CULTURE EVENTS FALL 2019 / WINTER 2020 ART AS RESISTANCE AGAINST OUR WARMING PLANET Shows, Concerts + Event Listings Inside Banff Centre is FALL 2019 / WINTER 2020 creativity that On the cover Features In every issue 12 Forever Emerging 3 President’s Letter can't be tamed. Governor General's 4 Event Highlights Award-winning author Some highlights from Katherena Vermette this season’s Banff on growing your Centre shows voice as a writer 6 Connect With Us 14 Art at the End Follow our InStudio of the World stories online Artists are responding Banff Centre is to the climate crisis. 8 From the Vault Who will listen? Get to know the artists behind some taking chances. 22 An Unbreakable Circle of the works from our Indigenous storytelling permanent collection in the digital age 10 Studio Visit 24 Leaving a Legacy Learn about one in the West of our Leighton Banff Centre's Artists Studios A 2015 PUBLIC ART INSTALLATION IN PARIS theatre undergoes titled Radical Action Reaction by visual artists renovations thanks to 28 Special Section and environmental activists Heather Ackroyd Banff Centre is a generous donation Explore Banff Centre and Dan Harvey frames an acorn tree as an campus this fall actor centre stage behind grass curtains. 30 Hide Couture and winter Years later, the installation is still reflective D'Arcy Moses' of the duo’s creative partnership, having Indigenous haute . 42 Open Studios spent years working with natural elements couture innovates on Peek into the studios to create art that challenges the material traditional practices of Banff Centre artists limits of their craft in order to challenge humanity’s relationship to the environment. -

Katherena Vermette’S (2016A) the Break, and Eden Robinson’S (2017A) Son of a Trickster

The understated power of reading contemporary Indigenous literature in Canada, a White supremacist nation by Halimah Beaulieu B.A. (Communications), Simon Fraser University, 2009 B.A. (English), Simon Fraser University, 2009 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Equity Studies in Education Program Faculty of Education © Halimah Beaulieu 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Halimah Beaulieu Degree: Master of Arts Title: The understated power of reading contemporary Indigenous literature in Canada, a White supremacist nation Examining Committee: Chair: Lucy Le Mare Professor Dolores van der Wey Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Ena Lee Supervisor Assistant Professor Daniel Heath Justice External Examiner Professor First Nations and Indigenous Studies University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: April 23, 2020 ii Abstract This thesis offers a textual analysis of three contemporary novels by Indigenous writers in Canada – Tracey Lindberg’s (2015) Birdie, Katherena Vermette’s (2016a) The Break, and Eden Robinson’s (2017a) Son of a Trickster. Informed by critical Whiteness studies, scholarship on settler colonialism, and reader response theory, I argue how contemporary Indigenous literature facilitates the social and political transformation decolonization requires. When approached with prior knowledge about past and ongoing colonialism, the stories written by today’s Indigenous authors disrupt the settler national myths that normalizes White supremacy in Canada and demands introspection on how settlers perpetuate colonial violence against First Peoples. Their stories extend possibilities for transformative learning by re-centering Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies, and by reframing kindness, reciprocity, and kinship as human obligations. -

Indigenous Authors Canada Spotlight

Indigenous Authors Canada Spotlight Audiobooks Comics eBooks No waiting. No late fees. Always available. Broaden your literary perspective. At hoopla, we’re committed to building a diverse collection that meets the needs of your patrons. When it comes to great titles, hoopla is adding to the thousands we already feature every week, including Canadian audiobooks, comics, and eBooks. Author David A. Robertson Indigenous graphic novelist and writer from Winnipeg, Manitoba. Of Swampy Cree heritage, Robertson has published over 25 books across a variety of genres. His first novel, The Evolution of Alice, was published in 2014. In 2017 he won Manuela Dias Book Design and Illustration Awards/ Graphic Novel Category for Will I See? and When We Were Alone, and the Governor General’s Literary Award. He was a contributor to the anthology Manitowapow: Aboriginal Writings from the Land of Water (2012). Author Christy Jordan-Fenton Author of four children’s books about Indian Residential School, published with Annick Press. Poetry, fiction, and creative non-fiction have appeared in Water~Stone Review, Prairie Fire, Jones Ave, and Quills. Author Katherena Vermette Canadian writer, who won the Governor General’s Award for English- language poetry in 2013 for her collection North End Love Songs. Vermette is of Métis descent and originates from Winnipeg, Manitoba. She was an MFA student in creative writing at the University of British Columbia. In addition to writing, Vermette advocates for the equality of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. 2 hoopladigital.com | CVS Midwest Tape | 1.866.698.2231 | 3875 McNicoll Avenue Unit 105, Toronto, Ontario, M1X 0C1 | cvsmidwesttape.ca Author Thomas King Thomas King has written several highly acclaimed children’s books. -

The Anishinaabe Worldview and the Child Reader in Louise Erdrich's the Birchbark House Series

The Anishinaabe Worldview and the Child Reader in Louise Erdrich's The Birchbark House Series Angela Joy Sparks Submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of PhD (Literature) May 2018 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the generous funding of the University of Hertfordshire Literature Bursary, for which I am grateful. I would like to thank my supervisory team, in particular Dr Rowland Hughes, for his patience, advice and support. I would also like to thank my husband Peter, who has encouraged me and supported me throughout this process. I am grateful to friends and colleagues from the University of Hertfordshire and the University of Northampton for their advice, support and friendship, and to the library services of those same institutions. Finally, I am forever grateful to my parents, without whose support and generosity I would not have had the opportunity to pursue this project. Abstract Louise Erdrich is an award-winning Anishinaabe-American author, whose works of fiction have attracted a significant body of scholarly interest. To date, her output of children's fiction has received comparatively less critical attention. This thesis is the first study to consider The Birchbark House series (published between 1999 and 2016) as a whole unit, in order to demonstrate its importance as a contributor to the perpetuation of Anishinaabe values amongst both Indigenous and settler children, and as a counter-hegemonic narrative. This thesis takes as its starting point the development of children's literature as a field of scholarly enquiry, using eXisting theoretical frameworks to situate The Birchbark House series within the discourse surrounding children's and young adult literature. -

Representation of Indigenous Education in Primary Classrooms

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Portfolios (Master of Education) 2020 Representation of Indigenous education in primary classrooms Creaser, Josie http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/4662 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons INDIGENOUS EDUCATION IN PRIMARY Representation of Indigenous Education in Primary Classrooms JOSIE CREASER A portfolio completed in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Education – Education for Change, with specialization in Social Justice Education Lakehead University © May 2020 INDIGENOUS EDUCATION IN PRIMARY 2 Abstract Throughout this portfolio, it is discussed how best to support teachers in addressing Indigenous culture throughout the curriculum, and more specifically, teaching Indigenous education to Early Learning Kindergarten age students. With the growing awareness and involvement of Indigenous education throughout Ontario schools, awareness of Indigenous culture is becoming an integral aspect in the daily classroom teachings and curriculum integration. However, there are few resources to support teachers to be confident in delivering the Indigenous education curriculum in an honest, culturally-, and developmentally-appropriate way. This is especially true in kindergarten where teachers may struggle to provide a balance with students’ emotional and intellectual maturity and the importance of Indigenous education. This portfolio addresses the ideologies and history of decolonization -

ROAD ALLOWANCE ERA a Girl Called ECHOVOL

ROAD ALLOWANCE ERA A Girl Called ECHOVOL. 4 Katherena Vermette Scott B. Henderson Donovan Yaciuk ROAD ALLOWANCE ERA A Girl Called ECHO VOL. 4 NOT FOR SALE FOR PROMOTIONAL USE ONLY By Katherena Vermette Illustrated by Scott B. Henderson Coloured by Donovan Yaciuk 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 T I M E L I N E O F T H E ROAD ALLOWANCE ERA 1870 The Manitoba Act is passed, establishing the new province, and granting 1.4 million acres of land to the Métis, as well as title to the land already farmed (approximately 2.5 million acres in all).1 1871 The Constitution Act gives the federal Parliament power to establish new provinces.2 Following the two-year reign of terror conducted by the Canadian Expeditionary Forces against the Métis of Red River, many disperse to the West. 1872 April 14 – Dominion Lands Act is passed, providing land grants to individuals, colonization companies, and religious groups to promote settlement of the West. Claims to Métis lands and First Nations reserves, though separate from these lands, continue to be delayed.3 1874–1875 Legislative amendments require those applying for land to prove “undisturbed occupancy,” with the result that many Métis lose their land patents as well as the right of appeal.4 1875 After five years’ delay, the Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie appoints representatives to verify land grant claimants. They underestimate the number of Métis children (entitled to land at age 21) at almost 2000 less than the 1870 census.5 Between 1873 and 1884, various amendments are passed that work against the Métis, and in favour of new settlers and unscrupulous land speculators. -

First Nations Reading List Fiction

First Nations Reading List This is a list of list suggested fiction, poetry and non-fiction books on First Nations topics. The focus is on books that are written by Indigenous authors, but the list also includes some non-Aboriginal contributors writing about issues relevant to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s process. Many books have a B.C. focus, and most are available in the Vancouver Island Regional Library system. The list is far from complete, and should be considered a work in progress. Some of the authors represented have several books which are all worthy of being included However in the interests of keeping the list manageable, in most cases only one book by each author is featured. If you discover an author on this list whose work speaks to you, consider seeking out other books they have written. Every effort has been made to ensure that the books on this list represent authentic First Nations voices and/or points of view. As such, most titles have been cross-referenced from multiple sources to ensure that they are genuinely well- regarded in the Indigenous community. Books can be windows into other cultures, and they can be doors. Through the act of reading we engage our imagination and open our minds. We learn, but we also dream. We hope that you find something on this list that will inspire you, challenge you, move you, and help to guide you on your own personal path of Truth and Reconciliation. We are all treaty people. Huy ch q'u siem Fiction Birdie by Tracy Lindberg, 2015 Birdie is a darkly comic and moving first novel about the universal experience of recovering from wounds of the past, informed by the lore and knowledge of Cree traditions.