DEIS for Washington Union Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E

AUA2020 Annual Meeting OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E. Washington Convention Center | Washington, DC HOTEL NAME RATES HOTEL NAME RATES Marriott Marquis Washington, D.C. 3 Night Min. $355 Kimpton George Hotel* $359 Renaissance Washington DC Dwntwn Hotel 3 Night Min. $343 Kimpton Hotel Monaco Washington DC* $379 Beacon Hotel and Corporate Quarters* $289 Kimpton Hotel Palomar Washington DC* $349 Cambria Suites Washington, D.C. Convention Center $319 Liaison Capitol Hill* $259 Canopy by Hilton Washington DC Embassy Row $369 Mandarin Oriental, Washington DC* $349 Canopy by Hilton Washington D.C. The Wharf* $279 Mason & Rook Hotel * $349 Capital Hilton* $343 Morrison - Clark Historic Hotel $349 Comfort Inn Convention - Resident Designated Hotel* $221 Moxy Washington, DC Downtown $309 Conrad Washington DC 3 Night Min $389 Park Hyatt Washington* $317 Courtyard Washington Downtown Convention Center $335 Phoenix Park Hotel* $324 Donovan Hotel* $349 Pod DC* $259 Eaton Hotel Washington DC* $359 Residence Inn Washington Capitol Hill/Navy Yard* $279 Embassy Suites by Hilton Washington DC Convention $348 Residence Inn Washington Downtown/Convention $345 Fairfield Inn & Suites Washington, DC/Downtown* $319 Residence Inn Downtown Resident Designated* $289 Fairmont Washington, DC* $319 Sofitel Lafayette Square Washington DC* $369 Grand Hyatt Washington 3 Night Min $355 The Darcy Washington DC* $296 Hamilton Hotel $319 The Embassy Row Hotel* $269 Hampton Inn Washington DC Convention 3 Night Min $319 The Fairfax at Embassy Row* $279 Henley Park Hotel 3 Night Min $349 The Madison, a Hilton Hotel* $339 Hilton Garden Inn Washington DC Downtown* $299 The Mayflower Hotel, Autograph Collection* $343 Hilton Garden Inn Washington/Georgetown* $299 The Melrose Hotel, Washington D.C.* $299 Hilton Washington DC National Mall* $315 The Ritz-Carlton Washington DC* $359 Holiday Inn Washington, DC - Capitol* $289 The St. -

7350 NBM Blueprnts/REV

MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Building in the Aftermath N AUGUST 29, HURRICANE KATRINA dialogue that can inform the processes by made landfall along the Gulf Coast of which professionals of all stripes will work Othe United States, and literally changed in unison to repair, restore, and, where the shape of our country. The change was not necessary, rebuild the communities and just geographical, but also economic, social, landscapes that have suffered unfathomable and emotional. As weeks have passed since destruction. the storm struck, and yet another fearsome I am sure that I speak for my hurricane, Rita, wreaked further damage colleagues in these cooperating agencies and on the same region, Americans have begun organizations when I say that we believe to come to terms with the human tragedy, good design and planning can not only lead and are now contemplating the daunting the affected region down the road to recov- question of what these events mean for the ery, but also help prevent—or at least miti- Chase W. Rynd future of communities both within the gate—similar catastrophes in the future. affected area and elsewhere. We hope to summon that legendary In the wake of the terrorist American ingenuity to overcome the physi- attacks on New York and Washington cal, political, and other hurdles that may in 2001, the National Building Museum stand in the way of meaningful recovery. initiated a series of public education pro- It seems self-evident to us that grams collectively titled Building in the the fundamental culture and urban char- Aftermath, conceived to help building and acter of New Orleans, one of the world’s design professionals, as well as the general great cities, must be preserved, revitalized, public, sort out the implications of those and protected. -

DEIS for Washington Union Station Expansion Project

Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Washington Union Station Expansion Project Appendix C1 – Methodology Report April 2018 Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Washington Union Station Expansion Project This page intentionally left blank. Environmental Impact Statement Methodology Report FINAL April 2018 Draft Final EIS Methodology Report Contents 1 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Regulatory Context ................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Study Areas ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.4 General – Analysis Years ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 General – Affected Environment ............................................................................................................................ 5 1.6 General – Evaluation Impacts ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.7 Alternatives -

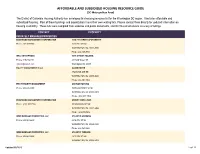

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

America's Catholic Church"

rfHE NATION'S CAPITAL CELEBRArfES 505 YEARS OF DISCOVERY HONORING THE GREA1" DISCOVERER CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS MONDAY OCTOBER 12. 1998 THE COLUMBUS MEMORIAL COLUMBUS PI~AZA - UNION STATION. W ASIIlNGTON. D.C. SPONSORED BY THE WASHINGTON COLUMBUS CELEBRATION ASSOCIATION IN COORDINATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CELEBRATING CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS IN THE NATION'S CAPITAL The Site In the years following the great quadricentennial (400th anniversary) celebration in 1892 of the achievements and discoveries of Christopher Cohnnbus, an effort was launched by the Knights of ~ Columbus to establish a monument to the ~ great discoverer. The U. S. Congress passed a law which mandated a Colwnbus Memorial in the nation's capital and appropriated $100,000 to cover the ~· ~, ·~-~=:;-;~~ construction costs. A commission was T" established composed of the secretaries of State and War, the chairmen of the House and Senate Committees on the Library of Congress, and the Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus. With the newly completed Union Railroad Station in 1907, plans focused toward locating the memorial on the plaz.a in front of this great edifice. After a series of competitions, sculptor Lorado Z. Taft of Chicago was awarded the contract. His plan envisioned what you see this day, a monument constructed of Georgia marble; a semi-circular fountain sixty-six feet broad and forty-four feet deep and in the center, a pylon crowned with a globe supported by four eagles oonnected by garland. A fifteen foot statue of Columbus, facing the U. S. Capitol and wrapped in!\ medieval mantle, stands in front of the pylon in the bow of a ship with its pn,, extending into the upper basin of the fountain terminating with a winged figurehead representing democracy. -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

Washington, D.C Site Form

New York Avenue , NE Corridor, Washington, DC Florida Avenue NE & S. Dakota Avenue NE The New York Avenue NE Corridor is located northeast Any framework for this area should consider how to of Downtown. It stretches for approximately 3 miles reduce emissions and promote climate resilience between Florida Avenue NE and South Dakota Avenue while strengthening connectivity, walkability, and NE. It is a major auto-oriented gateway into the city, urban design transitions to adjacent communities and with approximately 100,000 vehicles moving through open space networks, as well as the racial and social the area every day and limited public transit options. equity conditions necessary for long-term social resilience. Robust and sustainable transportation, DC’s Mayor has set ambitious goals for more utility, and civic facility infrastructure, along with affordable housing, and development along the public amenities, are critical to unlocking the corridor could support them. The goal is to deliver as corridor’s full potential. many as 33,000 new housing units, with at least 1/3 of these being affordable. Regeneration should yield a For this site, students can choose to develop a high- vibrant residential and jobs-rich, low-carbon, mixed- level framework or masterplan for the entire site, use corridor. It should be inclusive of new affordable which may include some details on some more specific and market-rate housing units, supported by solutions, such as massing, open space and building sustainable infrastructure and community facilities. type studies. Or, students can choose to design a more detailed response for one or more of these Regeneration will need to preserve some of the subareas, (possibly working in coordinated teams so character and activity of the existing light industrial that all 3 subareas are covered):1: Union Market- (or PDR – Production, Distribution & Repair) uses. -

Transportation Planning for the Richmond–Charlotte Railroad Corridor

VOLUME I Executive Summary and Main Report Technical Monograph: Transportation Planning for the Richmond–Charlotte Railroad Corridor Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation January 2004 Disclaimer: This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation solely in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof, nor does it express any opinion whatsoever on the merit or desirability of the project(s) described herein. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Any trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this report. Note: In an effort to better inform the public, this document contains references to a number of Internet web sites. Web site locations change rapidly and, while every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of these references as of the date of publication, the references may prove to be invalid in the future. Should an FRA document prove difficult to find, readers should access the FRA web site (www.fra.dot.gov) and search by the document’s title or subject. 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FRA/RDV-04/02 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date January 2004 Technical Monograph: Transportation Planning for the Richmond–Charlotte Railroad Corridor⎯Volume I 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Authors: 8. Performing Organization Report No. For the engineering contractor: Michael C. Holowaty, Project Manager For the sponsoring agency: Richard U. Cogswell and Neil E. Moyer 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. -

Fiscal Year 2021 Committee Budget Report

FISCAL YEAR 2021 COMMITTEE BUDGET REPORT TO: Members of the Council of the District of Columbia FROM: Councilmember Mary M. Cheh Chairperson, Committee on Transportation & the Environment DATE: June 25, 2020 SUBJECT: DRAFT Report and recommendations of the Committee on Transportation & the Environment on the Fiscal Year 2021 budget for agencies under its purview The Committee on Transportation & the Environment (“Committee”), having conducted hearings and received testimony on the Mayor’s proposed operating and capital budgets for Fiscal Year (“FY”) 2021 for the agencies under its jurisdiction, reports its recommendations for review and consideration by the Committee of the Whole. The Committee also comments on several sections in the Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Support Act of 2020, as proposed by the Mayor, and proposes several of its own subtitles. Table of Contents Summary ........................................................................................... 3 A. Executive Summary.......................................................................................................................... 3 B. Operating Budget Summary Table .................................................................................................. 7 C. Full-Time Equivalent Summary Table ............................................................................................. 9 D. Operating & Capital Budget Ledgers ........................................................................................... 11 E. Committee Transfers ................................................................................................................... -

Carnegie Library Rehabilitation and Exterior Restoration 801 K Street, NW, Washington, DC 20001 Mount Vernon Square (Reservation 8)

Carnegie Library Rehabilitation and Exterior Restoration 801 K Street, NW, Washington, DC 20001 Mount Vernon Square (Reservation 8) Concept Review Submission National Capital Planning Commission Filing Date: April 28, 2017 Meeting Date: June 1, 2017 Applicant Drawings Prepared by: Events DC c/o Jennifer Iwu FOSTER + PARTNERS Office of the President and CEO Riverside, 22 Hester Road 801 Mount Vernon Place, NW London SW11 4AN Washington, DC 20001 www.fosterandpartners.com [email protected] BEYER BLINDER BELLE Narrative Prepared by: ARCHITECTS & PLANNERS LLP 3307 M Street, NW, Suite 301 EHT TRACERIES, Inc. Washington, DC 20007 440 Massachusetts Ave., NW www.beyerblinderbelle.com Washington, DC 20001 www.traceries.com Carnegie Library Rehabilitation - NCPC Concept Submission April 28, 2017 | 1 CONTENTS Manhattan Laundry Mary Ann Shadd Cary House Project Narrative The Woodward The Lindens Existing Conditions 3 WashingtonWindsor Lodge DC Landmarks Lincoln Theatre Historical Overview 3 The Exeter General George B. McClellan Statue Basic Design Concept 4 Dunbar Theater Historic Preservation Documentation 4 Howard Theatre Environmental Documentation 4 Scottish Rite Temple Schedule 4 The Gladstone The Hawarden Funding 4 General Phillip H. Sheridan Statue Mackall Square Phillips Collection The Cairo Employment 4 The Lafayette Building Area and Site Coverage 4 Dumbarton Bridge General John A. Logan Statue Floodplain Management and Wetlands Protection 4 The Chamberlain O Street Market The Rhode Island Project Drawings Luther Place Memorial Church -

2013 Calendar

SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 2013 CALENDAR 800-925-5730 www.brookings.edu/execed [email protected] www.olin.wustl.edu/msl BEE 2013 calendar_no hole.indd 1 12/13/12 10:21 AM SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY JANUARY 800-925-5730 www.brookings.edu/execed MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. MEMORIAL [email protected] www.olin.wustl.edu/msl BEE 2013 calendar_no hole.indd 2 12/13/12 10:21 AM JANUARY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Legis Congressional Fellowship 1 NEW YEAR’S DAY 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Leading Innovation & Creating New Value INAUGURATION DAY MARTIN LUTHER 20 21 KING JR. DAY 22 23 24 25 26 Vision & Leading Change 27 28 29 30 31 800-925-5730 www.brookings.edu/execed [email protected] www.olin.wustl.edu/msl BEE 2013 calendar_no hole.indd 3 12/13/12 10:21 AM SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY FEBRUARY 800-925-5730 www.brookings.edu/execed LINCOLN MEMORIAL [email protected] www.olin.wustl.edu/msl BEE 2013 calendar_no hole.indd 4 12/13/12 10:21 AM FEBRUARY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 Politics 2013 Inside Congress: Understanding Congressional Operations Signature 3 4 Communications 5 6 7 8 9 Finance for Non-Financial Managers SES Boot Camp LINCOLN’S 10 11 12 BIRTHDAY 13 ASH WEDNESDAY 14 15 16 Strategies for Conflict Resolution PRESIDENTS’ DAY (WASHINGTON’S 17 18 BIRTHDAY) 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 800-925-5730 www.brookings.edu/execed [email protected] www.olin.wustl.edu/msl BEE 2013 calendar_no hole.indd 5 12/13/12 10:21 AM SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY MARCH COLUMBUS FOUNTAIN AT UNION STATION, WASHINGTON, D.C.