The Boston & Maine and Malden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Open Space and Recreation Plan

2015 OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN City of Melrose Office of Planning & Community Development City of Melrose Open Space and Recreation Plan Table of Contents Table of Contents Section 1: Plan Summary ............................................................................................................. 1-1 Section 2: Introduction ................................................................................................................. 2-1 A. Statement of Purpose ........................................................................................................... 2-1 B. Planning Process and Public Participation .......................................................................... 2-1 C. Accomplishments ................................................................................................................ 2-2 Section 3: Community Setting ..................................................................................................... 3-1 A. Regional Context ................................................................................................................. 3-1 B. History of the Community ................................................................................................... 3-3 C. Population Characteristics ................................................................................................... 3-4 D. Growth and Development Patterns ...................................................................................... 3-9 Section 4: Environmental Inventory and Analysis -

Medford, Massachusetts City Council Minutes

January 8, 2008 Medford City Council The First Regular Meeting Medford, Massachusetts January 8, 2008 Qualifying of Oath Alfred Pompeo, School Committee Paul Camuso, Council Michael Marks, Council Robert Penta, Council Stephanie M. Burke, Council Breanna Lungo-Koehn, Council City Council President Stephanie Muccini Burke Vice President Breanna Lungo-Koehn Paul A. Camuso Frederick N. Dello Russo, Jr. Robert A. Maiocco Michael J. Marks Robert M. Penta City Clerk Edward P. Finn the First Meeting of the Medford City Council at 7:00 P.M. at the Howard F. Alden Memorial Auditorium, Medford City Hall. ROLL CALL 7 Members Present SALUTE TO THE FLAG RECORDS The records of the meeting of December 18, 2007 were passed to Councillor Lungo-Koehn Those present and seated inside the rail were Dorothy Donehey, Asst. City Clerk and Lawrence Lepore, City Messenger Televised by Channel 16-Government Access 08-001- Election of a Council President for 2008 Councillor Lungo-Koehn nominated Stephanie Muccini Burke, seconded by Councillor Penta. Councillor Maiocco motioned that nominations be closed Roll Call Vote 7 in the affirmative for Stephanie Muccini Burke and 0 for no one else City Clerk/Justice of the Peace Edward P. Finn administered the Oath of Office to Elected President Stephanie Muccini Burke President Burke at this time assumed the chair 08-002-Election of a Council Vice President for 2008 Councillor Penta nominated Breanna Lungo-Koehn, seconded by Councillor Camuso, Councillor Camuso motioned that nominations be closed. Roll Call Vote 7 in the affirmative for Breanna Lungo-Koehn and 0 for no one else. -

Section 16 - ABP Progress & Expenditures Report, Run Date: 12/15/2015 10:08:00 AM Page 1 of 13 ESTIMATED COSTEXPENDITURES ESTIMATED SCHEDULE

ABP Progress and Expenditures Report Pursuant to 2008 Transportation Bond Act Chapter 233 §16 Data is current through 11/15/2015 This progress and expenditure report contains project expenditures incurred as of August 4, 2008 through the report date. This report may not reflect total project cost if the project incurred expenditures prior to August 4, 2008. Column Header Footnotes: 1 PRELIMINARY ESTIMATE - The preliminary estimate is not a performance measure for on-budget project delivery. It is the estimated construction cost value that was included in the November 30, 2008 report to the Legislature pursuant to §19 of Chapter 233 of the Acts of 2008; used for early budgeting purposes only. This “baseline” estimate was established at the inception of the program before many projects were scoped. This estimate included allowances for incidentals for construction such as police details, adjustment for inflation, and reasonable contingencies to account for growth approved by MassHighway/DCR. The Preliminary Estimate did NOT include costs associated with design, right-of-way, force accounts, project oversight, or other program related costs. * Indicates project is one of several that had an incorrect “Preliminary Estimate” and/or scheduled completion, as part of the Chapter 233 §19 Legislative requirement, to provide the estimates and schedules, as part of the 3 year plan of ABP. This Project had actual bid amounts and encumbered amounts, at the time of the filing of the Dec‐08 Legislative Report, but was not properly accounted for in the recording of the Dec‐08 Legislative Report. The Nov/Dec‐08 Conceptual Plan Chapter 233 §19 "Construct Cost" and/or "Completion" in this report reflect the corrected values as approved by the ABP Oversight Council at the March 8, 2010 Quarterly Meeting. -

City of Melrose Annual Report

CITY OF MELROSE MASSACHUSETTS Annual Reports 1917 WITH Mayor’s Inaugural Address DELIVERED JANUARY 2, 1917 PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF ALDERMEN UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CITY CLERK AND SPECIAL COMMITTEE THE KEYSTONE PRESS MELROSE, MASS. 1918 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Boston Public Library https://archive.org/details/cityofmelroseann1917melr INAUGURAL ADDRESS HON. CHARLES H. ADAMS MAYOR OF MELROSE DELIVERED JANUARY 2ND, 1917 Mr. Chairman, Members of the Board of Aldermen, Ladies and Gentlemen: At the beginning o£ the work for another year we should express our gratitude for the prosperity and advancemnt in 1916. Through the growth of the Cit> the extensive building operations, creating new property, we were able to reduce our tax rate without any general advance in property valuation. The rate was reduced from $23.70 to' $22.00. By the splendid progress of the City, the actual value of every property in Melrose was increased, but the value for taxation purposes Avas, with minor exceptions, not changed. We are able to so manage our affairs that the Budget was slightly less in 1916 than in 1915. How was it with you in your homes and in business? Did not your expenses increase in every line of expendi- ture? Did you buy anything so low in 1916 as before? On the whole, are you not surprised that our city has been able to get along without increasing your taxes? But all taxes are a burden, and a great burden to some, the subject of complaint and protest, often made by those best able to pay them, and we should seek to take from the people by taxation only the smallest amount possible for the needs of the city. -

Table 7: Non-Responders

Table 7, Non-responders: newspapapers not replying to the ASNE newsroom survey, ranked by circulation Rank Newspaper, State Circulation Ownership Community minority 1 New York Post, New York 590,061 46.0% 2 Chicago Sun-Times, Illinois 479,584 Hollinger 44.9% 3 The Columbus Dispatch, Ohio 251,557 15.8% 4 Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock, Arkansas 185,709 Wehco Media 22.6% 5 The Providence Journal, Rhode Island 165,880 Belo 16.3% 6 Las Vegas Review-Journal, Nevada 164,848 Stephens (Donrey) 39.2% 7 Journal Newspapers, Alexandria, Virginia 139,077 39.6% 8 The Post and Courier, Charleston, South Carolina 101,288 Evening Post 35.9% 9 The Washington Times, D.C. 101,038 46.7% 10 The Press Democrat, Santa Rosa, California 87,261 New York Times 25.0% 11 The Times Herald Record, Middletown, New York 84,277 Dow Jones 23.6% 12 The Times, Munster, Indiana 84,176 Lee 26.2% 13 Chattanooga Times Free Press, Tennessee 74,521 Wehco Media 16.4% 14 Daily Breeze, Torrance, California 73,209 Copley 66.5% 15 South Bend Tribune, Indiana 72,186 Schurz 13.9% 16 The Bakersfield Californian, California 71,495 51.2% 17 Anchorage Daily News, Alaska 69,607 McClatchy 29.0% 18 Vindicator, Youngstown, Ohio 68,137 13.3% 19 The Oakland Press, Pontiac, Michigan 66,645 21st Century 18.4% 20 Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, Ontairo, California 65,584 MediaNews 65.0% 21 Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Hawaii 64,305 80.0% 22 The Union Leader, Manchester, New Hampshire 62,677 5.1% 23 The Columbian, Vancouver, Washington 51,263 13.1% 24 The Daily Gazette, Schenectady, New York 51,126 -

Clippings Scrapbook II

Clippings Scrapbook II Items without a page number were inserted between pages. Genealogy of the Wehle Family of Prague “Brandeis—The Old Story of the Prophet” Boston American 6/4/1931 p.1‐3 Remarks by C.N. Jones October 1908 p.4‐5 “Former Louisville Man Leading Fight for the People’s Rights” Louisville Herald 6/1/1908 p.6‐7 “Stories of Success” Boston American 10/4/1908 p.8 “Louis Brandeis, Kentuckian, is Famed Fighter for People’s Rights” Louisville Herald 2/8/1910 p.9‐11 “Brandeis Sherlock Holmes’ Rival; Deductive Powers Amaze Enemies” Boston Traveler 6/10/1910 p.12‐13 “Personalities” Hampton Magazine June 1910 p.14‐19 “Brandeis, Teacher of Business Economy” New York Times 12/4/1910 p.20 12/5/1910 letter to New York Times from William F. Peters p.21 “An Attorney for the People” Outlook 12/24/1910 p.22‐24 “A Great American” Philadelphia North American 2/11/1911 p. 25 “Brandeis Refused Pay for Subway Lease Work” Boston Journal 2/25/1911 p.26 “’Citizen’ Brandeis” Boston Post 2/25/1911 p.27 “Louis Brandeis” The Electrical Worker February 1911 p.28 ? The World Today February 1911 p.29‐31 “Players in the Great Game” System February 1911 P.32‐37 “Who is This Man Brandeis?” Human Life February 1911 7/28/1880 letter from (Annie Fields ?) 8(?)/2/1880 letter from Charles Smith Bradley 1/26/1882 letter from J.O. Shaw Jr. (Union Boat Club) p.38‐50 “Brandeis” American Magazine February 1911 12/14/1883 letter from illegible 5/8/1884 letter from George H. -

CPY Document

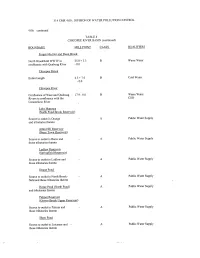

314 CMR 4.00 : DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL 06: continued TABLE 8 CHICOPEE RIVER BASIN (continued) BOUNDARY MILE POINT CLASS QUALIFIERS Forget-Me-Not and Dunn Brook North Brookfield WWTF to 25.0 + 3. Wann Water confluence with Quaboag River - 0. Chicopee Brook Entire Length 5 + 7. Cold Water - 0. Chicopee River Confluence of Ware and Quaboag 17. Wann Water Rivers to confluence with the CSO' Connecticut River Lake Mattawa North Pond Brook Reservoir) Source to outlet in Orange Public Water Supply and tributaries thereto Allen Hill Reservoir (Barre Town Reservoir Source to outlet in Barre and Public Water Supply those trbutaries thereto Ludlow Reservoir Springfield Reservoir) Source to outlet in Ludlow and Public Water Supply those tributaries thereto Doane Pond Source to outlet in North Brooke Public Water Supply field and those tributaries thereto Horse Pond (North Pond Public Water Supply and trbutaries thereto Palmer Reservoir (Graves Brook Upper Reservoir) Source to outlet in Palmer and Public Water Supply those trbutaries thereto Shaw Pond Source to outlet in Leicester and Public Water Supply those trbutaries thereto 314 CMR 4.00 : DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL 06: continued TABLE 8 CHICOPEE RIVER BASIN (continued) BOUNDARY MILE POINT CLASS OUALIFIERS Mare Meadow Reservoir Source to outlet in Hubbardston Public Water Supply and those trbutaries thereto Bickford Pond Source to outlet in Hubbardston Public Water Supply and those tributaries thereto Palmer Reservoir (Unnamed Reservoir Graves Brook Lower Reservoir Palmer Lower Reservoir Reservoir to outlet in Palmer and Public Water Supply those tributaries thereto Ouabbin Reservoir Reservoir to outlet in Ware and Public Water Supply those trbutaries thereto "" ", ! ..------ \.'"", - ",. -

Newspaper Distribution List

Newspaper Distribution List The following is a list of the key newspaper distribution points covering our Integrated Media Pro and Mass Media Visibility distribution package. Abbeville Herald Little Elm Journal Abbeville Meridional Little Falls Evening Times Aberdeen Times Littleton Courier Abilene Reflector Chronicle Littleton Observer Abilene Reporter News Livermore Independent Abingdon Argus-Sentinel Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Abington Mariner Livingston Parish News Ackley World Journal Livonia Observer Action Detroit Llano County Journal Acton Beacon Llano News Ada Herald Lock Haven Express Adair News Locust Weekly Post Adair Progress Lodi News Sentinel Adams County Free Press Logan Banner Adams County Record Logan Daily News Addison County Independent Logan Herald Journal Adelante Valle Logan Herald-Observer Adirondack Daily Enterprise Logan Republican Adrian Daily Telegram London Sentinel Echo Adrian Journal Lone Peak Lookout Advance of Bucks County Lone Tree Reporter Advance Yeoman Long Island Business News Advertiser News Long Island Press African American News and Issues Long Prairie Leader Afton Star Enterprise Longmont Daily Times Call Ahora News Reno Longview News Journal Ahwatukee Foothills News Lonoke Democrat Aiken Standard Loomis News Aim Jefferson Lorain Morning Journal Aim Sussex County Los Alamos Monitor Ajo Copper News Los Altos Town Crier Akron Beacon Journal Los Angeles Business Journal Akron Bugle Los Angeles Downtown News Akron News Reporter Los Angeles Loyolan Page | 1 Al Dia de Dallas Los Angeles Times -

Find It and Fix It Stormwater Program in the Charles and Mystic River Watersheds

FIND IT AND FIX IT STORMWATER PROGRAM IN THE CHARLES AND MYSTIC RIVER WATERSHEDS FINAL REPORT JUNE 2005 - AUGUST 2008 October 29, 2008 SUBMITTED TO: MASSACHUSETTS ENVIRONMENTAL TRUST EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICE OF GRANTS AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE 100 CAMBRIDGE STREET, 9TH FLOOR BOSTON, MA 02114 SUBMITTED BY: CHARLES RIVER WATERSHED ASSOCIATION MYSTIC RIVER WATERSHED ASSOCIATION 190 PARK ROAD 20 ACADEMY STREET, SUITE 203 WESTON, MA 02493 ARLINGTON, MA 02476 Table of Contents List of Figures................................................................................................................................. 3 List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 6 Organization of Report ................................................................................................................... 8 1.0 PROGRAM BACKGROUND............................................................................................ 9 1.1 Charles River.................................................................................................................. 9 1.1.1 Program Study Area................................................................................................ 9 1.1.2 Water Quality Issues............................................................................................ -

Middlesex County, Massachusetts (All Jurisdictions)

VOLUME 1 OF 8 MIDDLESEX COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS (ALL JURISDICTIONS) COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ACTON, TOWN OF 250176 ARLINGTON, TOWN OF 250177 Middlesex County ASHBY, TOWN OF 250178 ASHLAND, TOWN OF 250179 AYER, TOWN OF 250180 BEDFORD, TOWN OF 255209 COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER BELMONT, TOWN OF 250182 MELROSE, CITY OF 250206 BILLERICA, TOWN OF 250183 NATICK, TOWN OF 250207 BOXBOROUGH, TOWN OF 250184 NEWTON, CITY OF 250208 BURLINGTON, TOWN OF 250185 NORTH READING, TOWN OF 250209 CAMBRIDGE, CITY OF 250186 PEPPERELL, TOWN OF 250210 CARLISLE, TOWN OF 250187 READING, TOWN OF 250211 CHELMSFORD, TOWN OF 250188 SHERBORN, TOWN OF 250212 CONCORD, TOWN OF 250189 SHIRLEY, TOWN OF 250213 DRACUT, TOWN OF 250190 SOMERVILLE, CITY OF 250214 DUNSTABLE, TOWN OF 250191 STONEHAM, TOWN OF 250215 EVERETT, CITY OF 250192 STOW, TOWN OF 250216 FRAMINGHAM, TOWN OF 250193 SUDBURY, TOWN OF 250217 GROTON, TOWN OF 250194 TEWKSBURY, TOWN OF 250218 HOLLISTON, TOWN OF 250195 TOWNSEND, TOWN OF 250219 HOPKINTON, TOWN OF 250196 TYNGSBOROUGH, TOWN OF 250220 HUDSON, TOWN OF 250197 WAKEFIELD, TOWN OF 250221 LEXINGTON, TOWN OF 250198 WALTHAM, CITY OF 250222 LINCOLN, TOWN OF 250199 WATERTOWN, TOWN OF 250223 LITTLETON, TOWN OF 250200 WAYLAND, TOWN OF 250224 LOWELL, CITY OF 250201 WESTFORD, TOWN OF 250225 MALDEN, CITY OF 250202 WESTON, TOWN OF 250226 MARLBOROUGH, CITY OF 250203 WILMINGTON, TOWN OF 250227 MAYNARD, TOWN OF 250204 WINCHESTER, TOWN OF 250228 MEDFORD, CITY OF 250205 WOBURN, CITY OF 250229 Map Revised: July 7, 2014 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 25017CV001B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. -

Contents Our Lynde / Lynds Ancestors

Our Lynde / Lynds Ancestors By James C. Retson Last Revised November 1, 2020 Contents Our Lynde / Lynds Ancestors ................................................................................................................................. 1 Lynde\Lynds Context.............................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Thomas Lynde Say 1597 – 1671 ........................................................................................................................ 2 Dunstable, Bedford England ................................................................................................................................... 2 Charlestown, Massachusetts ................................................................................................................................... 5 Malden, Massachusetts ........................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Thomas Lynde 1615 – 1693 Elizabeth Tufts 1612 - 1693...................................................................................... 6 3. Captain John Lynde 1648 – 1723 ........................................................................................................................... 6 4. Thomas Lynde 1685 – 1761 Lydia Green 1685 - ................................................................................................... 7 Onslow Township ................................................................................................ -

HOUSE ...No. 4835

HOUSE . No. 4835 The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _______________ The committee of conference on the disagreeing votes of the two branches with reference to the Senate amendment (striking out all after the enacting clause and inserting in place thereof the text contained in Senate document numbered 2602) of the House Bill promoting climate change adaptation, environmental and natural resource protection, and investment in recreational assets and opportunity (House, No. 4613), reports recommending passage of the accompanying bill (House, No. 4835) [Bond Issue: $2,402,833,000.00] July 26, 2018. David M. Nangle William N. Brownsberger Smitty Pignatelli Anne M. Gobi Donald R. Berthiaume Donald F. Humason, Jr. 1 of 130 FILED ON: 7/26/2018 HOUSE . No. 4835 The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _______________ In the One Hundred and Ninetieth General Court (2017-2018) _______________ An Act promoting climate change adaptation, environmental and natural resource protection, and investment in recreational assets and opportunity. Whereas, The deferred operation of this act would tend to defeat its purpose, which is to forthwith provide for climate change adaptation and the immediate preservation and improvement of the environmental and energy assets of the commonwealth, therefore it is hereby declared to be an emergency law, necessary for the immediate preservation of the public convenience. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives in General Court assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows: 1 SECTION 1. To provide for