Wild Mammal Populations in Canterbury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Christchurch Tramper

TTHEHE CCHRISTCHURCHHRISTCHURCH TTRAMPERRAMPER Published by CHRISTCHURCH TRAMPING CLUB INC. PO Box 527, Christchurch, www.ctc.org.nz Affiliated with the Federated Mountain Clubs of NZ Inc. Any similarity between the opinions expressed in this newsletter and Club policy is purely coincidental. Vol. 79 December 2009/January 2010 No. 8 The CHRISTCHURCH TRAMPING CLUB has members of all ages, and runs tramping trips every weekend, ranging from easy (minimal experience required) to hard (high fitness and experience required). We also organise instructional courses and hold weekly social meetings. We have a club hut in Arthurs Pass and have gear available for hire to members. Membership rates per year are $40 member, $60 couple, $23 junior or associate, with a $5 discount for members who opt to obtain this newsletter electronically. Paske Hut in a Blizzard, June 2009 For more about how the club operates, see Ian Dunn's winning photo in the 2009 CTC photo contest More about the CTC. Contents Tramper of the Month 2 Events Calendar 5 Editorial 3 Trip Reports 21 News 3 More about the CTC 24 Obituaries 4 Classifieds & General Notices 24 Christmas Greetings from the Club Captain I hope that all Club Members and their families have a happy Christmas and New Year. To those of us heading into the outdoors have a great trip and return safely in the New Year. The Club has had a successful year with plenty of good tramps and it is particularly pleasing to welcome so many new members to the Club. Happy Christmas and a prosperous and safe New Year. -

Waimate District Licensing Committee Annual Report to the Alcohol Regulatory and Licensing Authority for the Year 2018 - 2019

Waimate District Licensing Committee Annual Report to the Alcohol Regulatory and Licensing Authority For the year 2018 - 2019 Date: 21 August 2019 Prepared by: Debbie Fortuin Environmental Compliance Manager Timaru District Council Introduction The purpose of this report is to inform the Alcohol Regulatory and Licensing Authority (the Authority) of the general activity and operation of the Waimate District Licensing Committee (DLC) for the year 2018 - 2019. There are three DLC’s operating in the South Canterbury area under a single Commissioner, this model having been adopted during the implementation of the Sale and Supply of Alcohol Act 2012 (the Act) in December of 2013. The three DLC’s are that of the Timaru, Waimate and Mackenzie Districts. This report will relate to the activities of all the DLC’s in the body of the text and to the Waimate DLC alone in the Annual Return portion of the report at the rear of this document. This satisfies the requirements of the territorial authority set out in section 199 of the Act. Overview of DLC Workload DLC Structure and Personnel The table below shows the current membership of the three DLC’s under the Commissioner. No changes occurred during the reporting period. Name Role Commissioner Sharyn Cain Deputy Mayor - Waimate District Council Timaru DLC Members Damon Odey Deputy Chair, Mayor - Timaru District Council David Jack Councillor - Timaru District Council Peter Burt Councillor - Timaru District Council Mackenzie DLC Members Graham Smith Mayor - Mackenzie District Council Chris Clarke Councillor – Mackenzie District Council Waimate DLC Members Craig Rowley Mayor - Waimate District Council Sheila Paul Councillor – Waimate District Council Total costs for the period amounted to $16,145.24. -

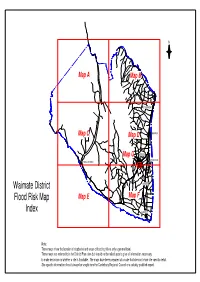

Flood Planning Maps A

N Map A Map B ST ANDREWS Map C Map D MAKIKIHI Map G WAIMATE STUDHOLME HAKATARAMEA Waimate District MORVEN Flood Risk Map Map E Map F Index GLENAVY Note: These maps show the location of stopbanks and areas of flooding risk at only a general level. These maps are referred to in the District Plan rules but should not be relied upon to give all information necessary to make decisions on whether a site is floodable. The maps have been prepared at a scale that does not show site-specific detail. Site specific information should always be sought from the Canterbury Regional Council or a suitably qualified expert. Note: These maps show the location of stopbanks and areas of flooding risk at only a general level. These maps are referred to in the District Plan rules but should notMackenzie be relied upon to District give all information necessary to make decisions on whether a site is floodable. The maps have Mackenzie District been prepared at a scale that does not show site-specific detail. Site specific information should always be sought from the Canterbury Regional Council or a suitably qualified expert. Hakataramea Downs H a k a t a r a m e a R i v e r Cattle Creek N Notations Flood Risk A B Stopbanks Map A C Area of Flooding Risk District Boundary 0 1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0km Scale 1:100000 @ A3 Location Diagram Date : February 2014 Note: Mackenzie District These maps show the location of stopbanks and areas of flooding risk at only a general level. -

Ag 22 January 2021

Since Sept 27 1879 Friday, January 22, 2021 $2.20 Court News P4 INSIDE FRIDAY COLGATE CHAMPIONSFULL STORY P32 COUNCILLORS DO BATTLE TO CAP RATES RISE P3 Ph 03 307 7900 Your leading Mid Canterbury real estate to subscribe! Teamwork gets results team with over 235 years of sale experience. Ashburton 217 West Street | P 03 307 9176 | E [email protected] Talk to the best team in real estate. pb.co.nz Property Brokers Ltd Licensed REAA 2008 2 NEWS Ashburton Guardian Friday, January 22, 2021 New water supplies on radar for rural towns much lower operating costs than bility of government funds being By Sue Newman four individual membrane treat- made available for shovel-ready [email protected] ment plants, he said. water projects as a sweetener for Councillor John Falloon sug- local authorities opting into the Consumers of five Ashburton gested providing each individu- national regulator scheme. District water supplies could find al household on a rural scheme This would see all local author- themselves connected to a giant with their own treatment system ities effectively hand over their treatment plant that will ensure might be a better option. water assets and their manage- their drinking water meets the That idea had been explored, ment to a very small number of highest possible health stand- Guthrie said, but it would still government managed clusters. ards. put significant responsibility on The change is driven by the Have- As the Ashburton District the council. The water delivered lock North water contamination Council looks at ways to meet the to each of those treatment points issue which led to a raft of tough- tough new compliance standards would still have to be guaranteed er drinking water standards. -

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 Sascha Nolden, Simon Nathan & Esme Mildenhall Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H November 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright Simon Nathan & Sascha Nolden, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H ISBN 978-1-877480-29-4 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) We gratefully acknowledge financial assistance from the Brian Mason Scientific and Technical Trust which has provided financial support for this project. This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Nolden, S.; Nathan, S.; Mildenhall, E. 2013: The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H. 219 pages. The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Sumner Cave controversy Sources of the Haast-Hooker correspondence Transcription and presentation of the letters Acknowledgements References Calendar of Letters 8 Transcriptions of the Haast-Hooker letters 12 Appendix 1: Undated letter (fragment), ca 1867 208 Appendix 2: Obituary for Sir Julius von Haast 209 Appendix 3: Biographical register of names mentioned in the correspondence 213 Figures Figure 1: Photographs -

Ecology of Red Deer a Research Review Relevant to Their Management in Scotland

Ecologyof RedDeer A researchreview relevant to theirmanagement in Scotland Instituteof TerrestrialEcology Natural EnvironmentResearch Council á á á á á Natural Environment Research Council Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ecology of Red Deer A research review relevant to their management in Scotland Brian Mitchell, Brian W. Staines and David Welch Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Banchory iv Printed in England by Graphic Art (Cambridge) Ltd. ©Copyright 1977 Published in 1977 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology 68 Hills Road Cambridge CB2 11LA ISBN 0 904282 090 Authors' address: Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Hill of Brathens Glassel, Banchory Kincardineshire AB3 4BY Telephone 033 02 3434. The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to and draws upon the collective knowledge of the fourteen sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a Sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man-made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. Nearly half of ITE'Swork is research commissioned by customers, such as the Nature Conservancy Council who require information for wildlife conservation, the Forestry Commission and the Department of the Environment. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. -

Mt Potts Lease Number

Crown Pastoral Land Tenure Review Lease name : Mt Potts Lease number : Pc 143 Conservation resources report As part of the process of tenure review, advice on significant inherent values within the pastoral lease is provided by Department of Conservation officials in the form of a conservation resources report. This report is the result of outdoor survey and inspection. It is a key piece of information for the development of a preliminary consultation document. The report attached is released under the Official Information Act 1982. Copied June 2003 RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT CONTENTS PART 1: Introduction.............................................................. 1 PART 2: Inherent Values......................................................... 2 2.1 Landscape.......................................................... 2 2.2 Landforms and Geology.................................... 7 2.3 Climate.............................................................. 8 2.4 Vegetation......................................................... 8 2.4.1 Original Vegetation............................... 8 2.4.2 Indigenous Plant Communities............. 9 2.4.3 Notable Flora....................................... 14 2.4.4 Problem Plants.....................................14 2.5 Fauna .............................................................15 2.5.1 Birds and Reptiles ............................... 15 2.5.2 Freshwater Fauna................................ 19 2.5.3 Invertebrates........................................ 21 2.5.4 Notable -

3 a CONSERVATION BLUEPRINT for CHRISTCHURCH Colin D

3 A CONSERVATION BLUEPRINT FOR CHRISTCHURCH Colin D. Meurk1 and David A. Norton2 Introduction To be 'living in changing times* is nothing new. But each new technological revolution brings an increasingly frantic pace of change. There has been a growing separation of decision-makers from the environmental consequences of their actions; there is a general alienation of people from the land, and there has been a corresponding quantum leap in environmental and social impacts. The sad and simple truth is that the huge advances in power and sophistication of our technology have not been matched by an equivalent advance in understanding and wise use of its immense power. From a natural history perspective the colonies of the European empires suffered their most dramatic changes compressed into just a few short centuries. In New Zealand over the past millenium, the Polynesians certainly left their mark on the avifauna in addition to burning the drier forests and shrublands. But this hardly compares with the biological convuolsions of the last century or so as European technology transformed just about all arable, grazable, burnable and millable land into exotic or degraded communities, regardless of their suitability for the new uses. Even today, 2 000 ha of scrub is burnt annually in North Canterbury alone. It is equally tragic, since the lessons from past mistakes are all too obvious, that there has persisted an ongoing, but barely discernible, attrition of those natural areas that survived the initial onslaught. Inevitably the greatest pressures have occurred in and around the major urban centres. The European settlers were primarily concerned with survival, development, and attempts to tame the unfamiliar countryside. -

Exploiting Interspecific Olfactory Communication to Monitor Predators

Ecological Applications, 27(2), 2017, pp. 389–402 © 2016 by the Ecological Society of America Exploiting interspecific olfactory communication to monitor predators PATRICK M. GARVEY,1,2 ALISTAIR S. GLEN,2 MICK N. CLOUT,1 SARAH V. WYSE,1,3 MARGARET NICHOLS,4 AND ROGER P. PECH5 1Centre for Biodiversity and Biosecurity, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, 1142 New Zealand 3Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Wakehurst Place, RH17 6TN United Kingdom 4Centre for Wildlife Management and Conservation, Lincoln University, Canterbury, New Zealand 5Landcare Research, PO Box 69040, Lincoln, 7640 New Zealand Abstract. Olfaction is the primary sense of many mammals and subordinate predators use this sense to detect dominant species, thereby reducing the risk of an encounter and facilitating coexistence. Chemical signals can act as repellents or attractants and may therefore have applications for wildlife management. We devised a field experiment to investigate whether dominant predator (ferret Mustela furo) body odor would alter the behavior of three common mesopredators: stoats (Mustela erminea), hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus), and ship rats (Rattus rattus). We predicted that apex predator odor would lead to increased detections, and our results support this hypothesis as predator kairomones (interspecific olfactory messages that benefit the receiver) provoked “eavesdropping” behavior by mesopredators. Stoats exhib- ited the most pronounced responses, with kairomones significantly increasing the number of observations and the time spent at a site, so that their occupancy estimates changed from rare to widespread. Behavioral responses to predator odors can therefore be exploited for conserva- tion and this avenue of research has not yet been extensively explored. -

South Canterbury Artists a Retrospective View 3 February — 11 March, 1990

v)ileewz cmlnd IO_FFIGIL PROJEEGT South Canterbury Artists A Retrospective View 3 February — 11 March, 1990 Aigantighe Art Gallery In association with South Canterbury Arts Society 759. 993 17 SOU CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 3 INTRODUCTION 6 BIOGRAPHIES Early South Canterbury Artists 9 South Canterbury Arts Society 1895—1928 18 South Canterbury Arts Society formed 1953 23 South Canterbury Arts Society Present 29 Printmakers 36 Contemporaries 44 CATALOGUE OF WORKS 62 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Page S.C. Arts Society Exhibition 1910 S.C. Arts and Crafts Exhibition 1946 T.S. Cousins Interior cat. I10. 7 11 Rev. J.H. Preston Entrance to Orari Gorge cat. I10. 14 13 Capt. E.F. Temple Hanging Rock cat. 1'10. 25 14 R.M. Waitt Te Weka Street cat. no. 28 15 F.F. Huddlestone Opawa near Albury cat. no. 33 16 A.L. Haylock Wreck of Benvenue and City of Perth cat. no. 35 17 W. Ferrier Caroline Bay cat. no. 36 18 W. Greene The Roadmakers cat. 1'10. 39 2o C.H.T. Sterndale Beech Trees Autumn cat. no. 41 22 D. Darroch Pamir cat. no. 45 24 A.J. Rae Mt Sefton from Mueller Hut cat. no. 7O 36 A.H. McLintock Low Tide Limehouse cat. no. 71 37 B. Cleavin Prime Specimens 1989 cat. no. 73 39 D. Copland Tree of the Mind 1987 cat. 1'10. 74 40 G. Forster Our Land VII 1989 cat. no. 75 42 J. Greig Untitled cat. no. 76 43 A. Deans Back Country Road 1986 cat. no. 77 44 Farrier J. -

Community Services and Development Committee

Notice is hereby given that a meeting is to be held of the Community Services and Development Committee To follow the District Infrastructure Committee meeting On Tuesday 26 January 2016 Council Chamber Waimate District Council Queen Street, Waimate Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the Community Services and Development Committee of the Waimate District Council will be held in the Council Chamber, Waimate District Council, Queen Street, Waimate, on Tuesday 26 January 2016 to follow the District Infrastructure Committee meeting. Committee Membership Peter Collins Chair Tom O’Connor Deputy Chair Craig Rowley Mayor Sharyn Cain Deputy Mayor David Anderson Councillor Arthur Gavegan Councillor Peter McIlraith Councillor Miriam Morton Councillor Sheila Paul Councillor Quorum – no less than five members Local Authorities (Members’ Interests) Act 1968 Councillors are reminded that if they have a pecuniary interest in any item on the agenda, then they must declare this interest and refrain from discussing or voting on this item and are advised to withdraw from the meeting table. Bede Carran Chief Executive Waimate District Council Community Services and Development Committee – 26 January 2016 2 Order of Business Agenda Item Page Apologies .............................................................................................................................. 4 Identification of Major or Minor Items not on the Agenda ....................................................... 5 Confirmation of Minutes – Community Services and Development -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day.