The Origin of the Paris Observatory Contributions to the Study of Early Modern Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The View from Rome

4/26/2019 The View From Rome » 2010 » April http://traditional-building.com/Steve_Semes/?m=201004 Go JAN FEB MAY ⍰ ❎ 51 captures 18 f 18 Feb 2012 - 8 Apr 2016 2011 2012 2013 ▾ About this capture The View From Rome Steven W. Semes Home About Steven W. Semes Our Other Blogs Clem Labine’s Traditional Building Clem Labine’s Period Homes Switcher Archive Archive for April, 2010 Can’t We Just Get Along? New and Old Buildings in Context April 15th, 2010 No comments What is the proper relationship between historical architecture and the production of new buildings and cities? Are architects and preservationists inevitably at odds, or is there a common objective that potentially unites them? Why do we assume that the architecture of the present and the architecture of the past are entirely different things that must be handled by entirely separate sets of experts? It is necessary to examine these questions in the light of a recovered traditional architecture and urbanism. The Louvre, Paris, shows how an architectural ensemble can grow over the course of centuries while maintaining essentially the same style. Within the courtyard, the central pavilion and the right half of the facade were designed by Jacques Lemercier to continue (and, in the case of the bays to the right of the center tower, to precisely imitate) the facade on the left half, built to the design of Pierre Lescot a century earlier. Photo: Steven W. Semes Historically, restoration or completion of old buildings and the design of new buildings were simply different aspects of a single discipline. -

DR. DOMINIQUE AUBERT DOB 10Th August 1978 - 31 Years French

DR. DOMINIQUE AUBERT DOB 10th August 1978 - 31 years French Lecturer Université de Strasbourg Observatoire Astronomique [email protected] http://astro.u-strasbg.fr/~aubert CURRENT SITUATION Lecturer at the University of Strasbourg, member of the Astronomical Observatory since September 2006. TOPICS RESEARCH • Formation of large structures in the Universe, Cosmology • Epoch of Reionization, galaxies, galactic dynamics, gravitational lenses • Numerical simulations, high performance computing, hardware acceleration of scientific computing on graphics cards (Graphics Processing Units - GPUs) CAREER • October 2005 - September 2006: Post-Doc CNRS, Service d'Astrophysique, CEA, Saclay, France. • April 2005 - October 2005: Max-Planck Institut fur Astrophysik, Garching, Germany, visitor. • April 2004-October 2004: Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK, Marie Curie visitorship. • October 2001-April 2005: PhD thesis "Measurement and implications of dark matter flows at the surface of the virial sphere", University Paris XI and Astronomical Observatory of Strasbourg. REFEERED PUBLICATIONS • Reionisation powered by GPUs I : the structure of the ultra-violet background, Aubert D. & Teyssier R., April 2010, submitted to ApJ, available on request, arXiv:1004.2503 • The dusty, albeit ultraviolet bright infancy of galaxies. Devriendt, J.; Rimes, C.; Pichon, C.; Teyssier, R.; Le Borgne, D.; Aubert, D.; Audit, E.; Colombi, S.; Courty, S; Dubois, Y.; Prunet, S.; Rasera, Y.; Slyz, A.; Tweed, D., Submitted to MNRAS, arXiv:0912.0376 • Galactic kinematics with modified Newtonian dynamics. Bienaymé, O.; Famaey, B.; Wu, X.; Zhao, H. S.; Aubert, D. A&A, April 2009, in press. • A particle-mesh integrator for galactic dynamics powered by GPGPUs. Aubert, D., Amini, M. & David, R. Accepted contribution to ICCS 2009. • Full-Sky Weak Lensing Simulation with 70 Billion Particles. -

Innovation and Sustainability in French Fashion Tech Outlook and Opportunities. Report By

Innovation and sustainability in French Fashion Tech outlook and opportunities Commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency and the Innovation Department of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in France December 2019 This study is commissioned by the Innovation Department of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in France and the Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO.nl). Written by Alice Gras and Claire Eliot Translated by Sophie Bramel pages 6-8 INTRODUCTION 7 01. Definition and key dates 8 02. Dutch fashion tech dynamics I 9-17 THE CONVERGENCE OF ECOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY IN FASHION 11-13 01. Key players 14 02. Monitoring impact 14-16 03. Sustainable innovation and business models 17 04. The impact and long-term influence of SDGs II 18-30 THE FRENCH FASHION INNOVATION LANDSCAPE 22-23 01. Technological innovation at leading French fashion companies 25-26 02. Public institutions and federations 27-28 03. Funding programmes 29 04. Independent structures, associations and start-ups 30 05. Specialised trade events 30 06. Specialised media 30 07. Business networks 30 08 . Technological platforms III 31-44 FASHION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH: CURRENT AND FUTURE OUTLOOK 34-35 01. Mapping of research projects 36-37 02. State of fashion research in France 38-39 03. Key fields of research in fashion technology and sustainability 40 04. Application domains of textile research projects 42-44 05. Fostering research in France IV 45-58 NEW TECHNOLOGIES TO INNOVATE IN THE FRENCH FASHION SECTOR 47 01. 3D printing 48 02. 3D and CAD Design 49-50 03. Immersive technologies 51 04. -

PDF Program Book

46th Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences with Historical Astronomy Division (HAD) 9-14 November 2014 | Tucson, AZ OFFICERS AND MEMBERS ........ 2 SPONSORS ............................... 2 EXHIBITORS .............................. 3 FLOOR PLANS ........................... 5 ATTENDEE SERVICES ................. 8 Session Numbering Key SCHEDULE AT-A-GLANCE ........ 10 100s Monday 200s Tuesday SUNDAY ................................. 20 300s Wednesday 400s Thursday MONDAY ................................ 23 500s Friday TUESDAY ................................ 44 Sessions are numbered in the program book by day and time. WEDNESDAY .......................... 75 All posters will be on display Monday - Friday THURSDAY.............................. 85 FRIDAY ................................. 119 Changes after 1 October are included only in the online program materials. AUTHORS INDEX .................. 137 1 DPS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS Current DPS Officers Heidi Hammel Chair Bonnie Buratti Vice-Chair Athena Coustenis Secretary Andrew Rivkin Treasurer Nick Schneider Education and Public Outreach Officer Vishnu Reddy Press Officer Current DPS Committee Members Rosaly Lopes Term Expires November 2014 Robert Pappalardo Term Expires November 2014 Ralph McNutt Term Expires November 2014 Ross Beyer Term Expires November 2015 Paul Withers Term Expires November 2015 Julie Castillo-Rogez Term Expires October 2016 Jani Radebaugh Term Expires October 2016 SPONSORS 2 EXHIBITORS Platinum Exhibitor Silver Exhibitors 3 EXHIBIT BOOTH ASSIGNMENTS 206 Applied -

Download the Press Release. (144.32

16 July 2020 PR084-2020 ESA RELEASES FIRST IMAGES FROM SOLAR ORBITER The European Space Agency (ESA) has released the first images from its Solar Orbiter spacecraft, which completed its commissioning phase in mid-June and made its first close approach to the Sun. Shortly thereafter, the European and U.S. science teams behind the mission’s ten instruments were able to test the entire instrument suite in concert for the first time. Despite the setbacks the mission teams had to contend with during commissioning of the probe and its instruments in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first images received are outstanding. The Sun has never been imaged this close up before. During its first perihelion, the point in the spacecraft’s elliptical orbit closest to the Sun, Solar Orbiter got to within 77 million kilometres of the star’s surface, about half the distance between the Sun and Earth. The spacecraft will eventually make much closer approaches; it is now in its cruise phase, gradually adjusting its orbit around the Sun. Once in its science phase, which will commence in late 2021, the spacecraft will get as close as 42 million kilometres, closer than the planet Mercury. The spacecraft’s operators will gradually tilt its orbit to get the first proper view of the Sun’s poles. Solar Orbiter first images here Launched during the night of 9 to 10 February, Solar Orbiter is on its way to the Sun on a voyage that will take a little over two years and a science mission scheduled to last between five and nine years. -

The Synoptic Scientific Image in Early Modern Europe*

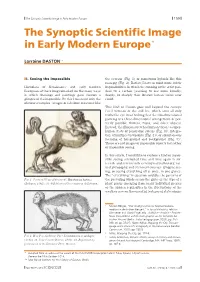

| The Synoptic Scientific Image in Early Modern Europe | 159 | The Synoptic Scientific Image in Early Modern Europe * Lorraine DASTON ** T I. Seeing the Impossible the centaur (Fig. 1) or monstrous hybrids like this man-pig (Fig. 2). Rather, I have in mind more subtle Historians of Renaissance and early modern impossibilities, in which the cunning of the artist pan - European art have long remarked on the many ways ders to a certain yearning to see more broadly, in which drawings and paintings gave viewers a deeply, or sharply than located human vision ever glimpse of the impossible. By this I mean not only the could. obvious examples : images of fabulous creatures like This kind of illusion goes well beyond the trompe l’oeil mimesis of the still life, which after all only tricks the eye into thinking that the two-dimensional painting is a three-dimensional arrangement of per - fectly possible flowers, fruits, and other objects. Instead, the illusion stretches human vision to super - human feats of panoramic sweep (Fig. 3) 1, integra - tion of multiple viewpoints (Fig. 4) 2, or simultaneous focusing of foreground and background (Fig. 5) 3. These are not images of impossible objects but rather of impossible seeing. In this article, I would like to explore a kind of impos - sible seeing attempted time and time again in six - teenth- and seventeenth-century natural history, nat - ural philosophy, and even mathematics : synoptic see - ing, or seeing everything all at once, in one glance. The “ everything ” in question could be the patterns of Fig. 1. Centaur, Ulisse Aldrovandi, Monstrorum historia the prevailing winds across the globe or the type of a (Bologna, 1642) : 31. -

Toads and Plague: Amulet Therapy in Seventeenth-Century Medicine Author(S): MARTHA R

Toads and Plague: Amulet Therapy in Seventeenth-Century Medicine Author(s): MARTHA R. BALDWIN Source: Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Summer 1993), pp. 227-247 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44444207 Accessed: 02-07-2018 17:14 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the History of Medicine This content downloaded from 132.174.255.223 on Mon, 02 Jul 2018 17:14:29 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Toads and Plague: Amulet Therapy in Seventeenth-Century Medicine MARTHA R. BALDWIN The seventeenth century witnessed a sharp interest in the medical applications of amulets. As external medicaments either worn around the neck or affixed to the wrists or armpits, amulets enjoyed a sur- prising vogue and respectability. Not only does this therapy appear to have been a fashionable folk remedy in the seventeenth century,1 but it also received acceptance and warm enthusiasm from learned men who strove to incorporate the curative and prophylactic benefits of amulets into their natural and medical philosophies. -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

Domaine National Du Palais Royal -Bury Fountain

LOCATIONS N°49914 updated: 05/28/2020 Domaine National du Palais Royal -Bury fountain 75001 Paris France Contact the commission Film Paris Region, Ile-de-France Film Commission | +33 (0)1 75 62 58 07 Credits: www.l'artnouveau.com Credits: Commission du Film d'Ile-de-France Caption: Caption: Credits: Commission du Film d'Ile-de-France Credits: Commission du Film d'Ile-de-France Caption: Caption: Credits: Commission du Film d'Ile-de-France Caption: LOCATION TYPE CATEGORIES YARD Fountain ENVIRONMENT City GENERAL PRESENTATION LOCATION CONDITION TYPE Well maintained LOCATION HISTORY After the wall Charles V had built around Paris was torn down, Cardinal de Richelieu asked Jacques Lemercier to construct a monumental palace with a large garden near the Louvre (1634). For a long time, the palace was called the Palais Cardinal, before becoming what it is today: the Palais Royal. The prelate gave the house to the crown in 1636, and it was the residence of the Orléans family from 1661 and even became a center of power during the Regency. The main wing, which faces the Louvre, was finished and remodeled by Contant d’Ivry in the 18th century, then by Fontaine in the 19th century. The theater, today the seat of the Théâtre français, burned down on several occasions and was rebuilt in 1791. At the end of the 18th century, Louis-Philippe d’Orléans (the future Philippe-Egalité) needed money and launched a major real estate development project in 1780. He commissioned Victor Louis to build apartment buildings with identical facades around the three sides of the garden. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 01 May 2019 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Bi§cak,Ivana (2020) 'A guinea for a guinea pig : a manuscript satire on England's rst animalhuman blood transfusion.', Renaissance studies., 34 (2). pp. 173-190. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12571 Publisher's copyright statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Bi§cak,Ivana (2020). A guinea for a guinea pig: a manuscript satire on England's rst animalhuman blood transfusion. Renaissance Studies 34(2): 173-190 which has been published in nal form at https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12571. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk A Guinea for a Guinea Pig: A Manuscript Satire on England’s First Animal-Human Blood Transfusion1 Utilis est rubri, qvæ fit, transfusio succi, At metus est, homo ne candida fiat ovis. -

Sara Galletti Le Palais Du Luxembourg De Marie De Médicis 1611–1631 the Luxembourg Palace Is One of Those Rare Early Modern B

Books Sara Galletti penetrates the restrictive and often-secretive building reports. Here, Galletti traces the Le palais du Luxembourg de Marie social life of the court, to show us how alterations made to the building as the de Médicis 1611–1631 many rooms there were, how they were property changed hands, from Maria’s Trans. Julien Noblet; Paris: Éditions Picard, used, and who was admitted to them. The death in 1642 through the mid-eighteenth 2012, 294 pp., 6 color and 165 b/w illus. second advance in our understanding of the century. As few of the original plans survive, €53.00, ISBN 9782708409354 building is contained in the final chapter, historians have often relied on later draw- which undertakes a careful architectural ings and depictions, made for different The Luxembourg Palace is one of those and iconographic reading of the palace. purposes. Some of these, as Galletti shows, rare early modern buildings that remains Inspired very self-consciously by the Pitti are more reliable than others. Casual read- central to the day-to-day life of a capital city. Palace in Florence, the Luxembourg reveals ers may find this chapter hard going. The This national landmark today houses the much about the perception and reception discussion is largely descriptive and, to Sénat, the upper chamber of the French of Italian architecture in France, during a the extent that it leaves behind the figure parliament, while from the garden, it is crucial period in the evolution of French of Maria, detaches itself somewhat from familiar to countless Parisians and tourists. -

LBF Locke 12333 Front

A Letter Concerning Toleration and Other Writings John Locke the thomas hollis library David Womersley, General Editor John Locke: A Letter Concerning Toleration and Other Writings Edited and with an Introduction by Mark Goldie liberty fund Indianapolis This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest- known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 b.c. in the Sumerian city- state of Lagash. Introduction, editorial additions, and index © 2010 by Liberty Fund, Inc. All rights reserved Frontispiece: Engraved portrait of John Locke that prefaces Thomas Hollis’s 1765 edition of Letters Concerning Toleration. Reproduced by courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Locke, John, 1632–1704. [Epistola de tolerantia. English] A letter concerning toleration and other writings/John Locke; edited by David Womersley and with an introduction by Mark Goldie. p. cm.—(The Thomas Hollis Library) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-86597-790-7 (hc: alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-86597-791-4 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Toleration—Early works to 1800. I. Womersley, David. II. Goldie, Mark. III. Title.