Quality and Equity by Design: Charting the Course for the Next Phase of Competency-Based Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of SDAS 1997

Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science Volume 76 1997 Published by the South Dakota Academy of Science Academy Founded November 22, 1915 Editor Kenneth F. Higgins Terri Symens, Wildlife & Fisheries, SDSU provided secretarial assistance Tom Holmlund, Graphic Designer We thank former editor Emil Knapp for compiling the articles contained in this volume. TABLE OF CONTENTS Minutes of the Eighty-Second Annual Meeting of the South Dakota Academy of Science........................................................................................1 Presidential Address: Can we live with our paradigms? Sharon A. Clay ..........5 Complete Senior Research Papers presented at The 82nd Annual Meeting of the South Dakota Academy of Science Fishes of the Mainstem Cheyenne River in South Dakota. Douglas R. Hampton and Charles R. Berry, Jr. ...........................................11 Impacts of the John Morrell Meat Packing Plant on Macroinvertebrates in the Big Sioux River in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Craig N. Spencer, Gwen Warkenthien, Steven F. Lehtinen, Elizabeth A. Ring, and Cullen R. Robbins ...................................................27 Winter Survival and Overwintering Behavior in South Dakota Oniscidea (Crustacea, Isopoda). Jonathan C. Wright ................................45 Fluctuations in Daily Activity of Muskrates in Eastern South Dakota. Joel F. Lyons, Craig D. Kost, and Jonathan A. Jenks..................................57 Occurrence of Small, Nongame Mammals in South Dakota’s Eastern Border Counties, 1994-1995. Kenneth F. Higgins, Rex R. Johnson, Mark R. Dorhout, and William A. Meeks ....................................................65 Use of a Mail Survey to Present Mammal Distributions in South Dakota. Carmen A. Blumberg, Jonathan A. Jenks, and Kenneth F. Higgins ................................................................................75 A Survey of Natural Resource Professionals Participating in Waterfowl Hunting in South Dakota. Jeffrey S. Gleason and Jonathan A. -

Oversight Hearing on Runaway and Homeless Youth. Hearing Before the Subcommitte on Human Resources of the Committee on Education and Labor

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 264 452 CG 018 680 TITLE Oversight Hearing on Runaway and Homeless Youth. Hearing before the Subcommitte on Human Resources of the Committee on Education and Labor. House of Representatives, Ninety-Ninth Congress, First Session. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. House Committee on Education and Labor. PUB DATE 25 Jul 85 NOTE 186p.; Serial No. 99-23. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; Children; *Child Welfare; Family Problems; Federal Programs; Hearings; *Homeless People; Legislation; *Runaway5; Youth Agencies; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Congress 99th; *Runaway and Homeless Youth Act 1974 ABSTRACT This document contains witnesses testimonies from the Congressional hearing on runaway and homeless youth calledto examine the problem of runaway children and the relationship betweenrunaway and missing children services. In his opening statement Representative Kildee recognizes benefits of theRunaway and Homeless Youth Act. Six witnesses give testimony: (1) June Bucy, executive director of the National Network of Runaway and Youth Services; (2) Dodie Livingston, commissioner of the Administration for Children. Youth and Families, Department of Health and Human Services; (3) Mike Sturgis, a former runaway; (4) Ted Shorten, executive director, Family Connection, Houston, Texas; (5) Twila Young;a family youth coordinator, Iowa Runaway, Homeless, and Missing Youth Services Network, Inc.; and (6) Dick Moran, executive director of Miami Bridge, Miami, Florida. Witnesses praise the Runaway andHomeless Youth Act, giving examples of the successful programs funded by this act. June Bucy describes the increasing need forrunaway youth services and their funding. Twila Young discusses the lack ofrunaway services in rural areas. -

Np 084 25.Pdf

u Your guide to fitness and wellnes •' •!• Greater Newark's Hometown Newspaper Since 1910 •!• ~------------------------------------------------ -- --- 84th Year, Issue 25 @ 1994 For the week beginning July 8, 1994 Newark, Del. • 35¢ TillS WEEK Decision nears on LIBER1Y DAY FFsnvrriES In sports 200-home site here Vote scheduled at July 11 council meeting By JENNIFER L. RODGERS which is willed to DuPont's gra nl children. NEWARK POST STAF F WRITER A publ ic hearing to dis uss the ho using plan during Newark Land located between William Pl;mning Commission's May 3rd M . Re dd Park and Curti s Mill meetin g un vei led concerns about Road may be designated as the site traffic, the number of units-ori gi for 200 new homes at Newark City nally 275 homes were proposed, Counci l's July II meeting at 8 and th e absence of bike paths as p.m. reasons for the commission tu rec The 74.12 acres of la nd pro ommend again st the pl an. posed for development are part of However , a traffi c analyses 253 acres of DuPont prope rty compiled by eng ineers at Telra annexed by the c ity in 1989. Tech, In c. , sa id traffic volumes Initiall y, it was ag reed the land ha ve decreased at both intersec would be used for a 600,000 ti o ns- w he re C urtis Mill Road square-foot office building and intersects with C leveland Avenue wi ll remain slated for such use, if and at Possum Park Road- th at the rezoning from man ufacturing lead ro the proposed development s. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Career Fair June 4, 2018

Career Fair June 4, 2018 Abigail Kirsch Catering Relationships www.abigailkirsch.com Table 21 Abigail Kirsch is known for its outstanding cuisine and event management always delivering superb food, impeccable service and C unmistakable flair. Abigail Kirsch is the area’s first choice for the best execution in weddings, corporate events, galas and social BP functions. What started as a small business serving predominately Westchester and Fairfield Counties quickly expanded to include Manhattan and the entire tri-state area. In 1990 the Kirschs opened Tappan Hill Mansion and began operating their first exclusive venue. Since Tappan Hill, the family has added Pier Sixty, The Lighthouse, Current, The Loading Dock and The Skylark to their exclusive venue portfolio. The Off Premise Catering Division brings the same standard of distinctive food service to any other location a client may choose. Today Abigail Kirsch Catering Relationships is recognized as the market leader for excellence in the greater New York metropolitan area. At the core of its success is an obsessive commitment to perfection. The Kirschs recognized early on that their business was only as successful as their last event. With this focus as a cornerstone, all associates work in unison to provide extraordinary guest experiences. Recruiting for: Full Time Crew Leaders - Externs Sarah Saracino Human Resources Manager 81 Highland Avenue Tarrytown NY 10591 [email protected] (914) 631-3447 Priscilla Gonzalez Senior HR Specialist [email protected] Adams Fairacre Farms www.adamsfarms.com Table 23 There are four Adams stores around the Hudson River Valley - in Poughkeepsie, Kingston, Newburgh, and Wappinger. We started as a farmstand in 1919, and expanded our offerings to include a full-service bakery, extensive Prepared Food Department, meat department, and specialty foods. -

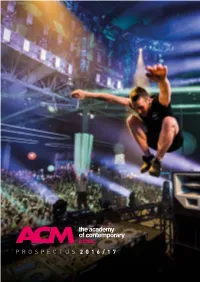

P R O S P E C T U S 2016/17

PROSPECTUS 2016/17 Contents Welcome to ACM ...................................... 4 BA(Hons) Music Industry Practice Education Management Team .................. 6 BA(Hons) Music Industry Practice (MIP) ......... 40 The Foundation Year (Level 0) .......................... 43 Why Choose ACM? Music Industry Practice Structure ................. 46 The BA(Hons) Years ........................................ 49 Why Choose ACM? ..................................... 8 The Musician Study Route ............................... 50 Sterling Williams: Student Interview ...... 10 The Creative Artist Study Route ..................... 54 Facilities .................................................. 12 The Producer Study Route ............................... 58 Tutors ...................................................... 14 The Technical Services Study Route ............... 62 Industry Link ........................................... 16 The Business & Innovation Study Route ......... 64 Metropolis Studios ................................. 18 Elective Modules ............................................. 68 Songwriting at ACM ............................... 20 Destinations .................................................... 72 Masterclasses ......................................... 22 An Enriched Student Experience ........... 24 BTEC Level 3 Extended Diploma Wellbeing & Mindfulness ........................ 25 Technology @ ACM .................................. 26 BTEC Level 3 Extended Diploma Study ............ 75 Accommodation ...................................... -

Mitchell, Mullin Win Christina Seats

THIS WEEK IN SPORTS + serving Greater Newark Since 1910 •> Published every Friday May 14, 1993 Mitchell, Mullin win Christina seats By Eric Fine "Bud" Mullin team that put the first years of desegregation. Post Staff Reporter defeated Georgi~ Christina on the The court order, which is still in A. Wampler 429 cutting edge of effect today, mandates busing of Two incumbents who between votes to 390 educational Newark children to Wilmington them had sat on the Christina board votes. reform. We've schools for three years and of education for nearly two decades Both Mullin left behind a Wilmington children to Newark were defeated during last and Mitchell solid foundation schools for nine years. Saturday's election. begin their five for the new "Everyone was feeling uncer First-time challenger Susan V. year terms dur- 1 board mem tain," Wampler said. 'The goal was Mitchell defeated Janet' Crouse, bers." just to get things up and running E. Fine photo/The Post ing the . July Susan Mitchell who had been a board member for board meetmg. Looking and having people comfortable The Delaware Wizard's Darlusz Bujak and his six years, 406 votes to 343 votes; "I'm proud of the contributions back on her 12 years as board with our schools." Education issues Connecticut Wolves opponent baHie It out at Glasgow first-time challenger Jean Craze I've made to the school board," member, Wampler, 45, said, "If I were given Jess priority until that stadium In United States Inter-divisional Soccer League Bailey who also was on the ballot said Crouse, 50, after Tuesday's made a difference, I'm satisfied." goal was met, she said. -

Kalafatas.Pdf

The Bellstone b THE BELLSTONE The Greek Sponge Divers of the Aegean One American’s Journey Home b MICHAEL N. KALAFATAS Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London brandeis university press Published by University Press of New England, 37 Lafayette St., Lebanon, NH 03766 ᭧ 2003 by Brandeis University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 54321 Includes the epic poem “Winter Dream” by Metrophanes I. Kalafatas written in 1903 and published in Greek by Anchor Press, Boston, 1919. The poem appears in full both in its English rendering by the poet Olga Broumas, published here for the first time, and in the original Greek, in chapters 11 and 12. “Harlem (2)” on page 161. Reprinted by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated. From THE COLLECTED POEMS OF LANGSTON HUGHES by Langston Hughes, copyright ᭧ 1994 by The Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. Title page illustration: Courtesy Demetra Bowers, from a holograph copy of the poem by Metrophanes Kalafatas. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kalafatas, Michael N. The bellstone : the Greek sponge divers of the Aegean / Michael N. Kalafatas. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1–58465–272–1 1. Sponge divers—Greece—Dodekanesos—History. 2. Sponge fisheries—Greece—Dodekanesos—History. 3. Sponge divers—Greece—Dodekanesos—Poetry. I. Title. HD8039.S55552 G763 2003 331.7'6397—dc21 2002153371 For Joan, for the children, and for those so loved now gone b And don’t forget All through the night The dead are also helping —Yannis Ritsos, from “18 Thin Little Songs of the Bitter Homeland” The poem is like an old jewel buried in the sand. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JULY 22, 2021 No. 129 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was forward and lead the House in the Madam Speaker, I am hopeful and called to order by the Speaker. Pledge of Allegiance. sincerely believe that we can build f Mr. GROTHMAN led the Pledge of back better, and our children’s future Allegiance as follows: can be assured. PRAYER I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the f The Chaplain, the Reverend Margaret United States of America, and to the Repub- Grun Kibben, offered the following lic for which it stands, one nation under God, ACTIONS AND RESULTS SPEAK prayer: indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. LOUDER THAN WORDS Gracious and loving God, hear our f (Mr. KELLER asked and was given prayers. We come to You in faith hop- permission to address the House for 1 ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER ing that You would receive our con- minute.) cerns, spoken and unspoken, personal The SPEAKER. The Chair will enter- Mr. KELLER. Mr. Speaker, actions and professional. From the depth of tain up to five requests for 1-minute and results speak louder than words. Your infinite mercy, listen to us, and speeches on each side of the aisle. In the months since President Biden bless all that troubles us. f first called for unity and bipartisan co- Then enable us to listen for Your re- operation, the President’s and Speak- 200 DAYS OF DELIVERING FOR THE sponse. -

Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism English, Department of January 1911 Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads John A. Lomax M.A. University of Texas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Lomax, John A. M.A., "Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads" (1911). University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism. 12. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. COWBOY SONGS AND OTHER FRONTIER BALLADS COLLECTED BY * * * What keeps the herd from running, JOHN A. LOMAX, M. A. THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS Stampeding far and wide? SHELDON FELLOW FOR THE INVESTIGATION 1)F AMERICAN BALLADS, The cowboy's long, low whistle, HARVARD UNIVERSITY And singing by their side. * * * WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY BARRETT WENDELL 'Aew moth STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY I9Il All rights reserved Copyright 1910 <to By STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY MR. THEODORE ROOSEVELT Set up lUld electrotyped. Published November, 1910 WHO WHILE PRESIDENT wAs NOT TOO BUSY TO Reprinted April, 1911 TURN ASIDE-CHEERFULLY AND EFFECTIVELY AND AID WORKERS IN THE FIELD OF AMERICAN BALLADRY, THIS VOLUME IS GRATEFULLY DEDICATED ~~~,. < dti ~ -&n ~7 e~ 0(" ~ ,_-..~'t'-~-L(? ~;r-w« u-~~' ,~' l~) ~ 'f" "UJ ":-'~_cr l:"0 ~fI."-.'~ CONTENTS ::(,.c.........04.._ ......_~·~C&-. -

Ufos Above Newark? 1• •• by Diane Heck Friend Had Stepped out of the Meet Who Wishes to Remain Anonym Ous, No Noise of a Plane Or Helicopter

' THIS WEEK IN SPORTS '• SeJVIng Greater Newark Since 191 0 •:• Published every Friday June 11, 1993 35e UFOs above Newark? 1• •• By Diane Heck friend had stepped out of the meet who wishes to remain anonym ous, no noise of a plane or helicopter. Post Community Editor ing at the Unitarian Universalist was driving home from the meeting So on it was hovering di rectly Fellowship in Newark to use the on I-95 North at approx im ately above me, and I saw that it was A strong form of cosmic energy restrooms in the other building 9:15 p.m. It was raining and she shaped li ke an equilateral triangle. permeated the room during the when he looked up and saw a large was near the rest stop in Newark One corn er had a while light, the Extraterrestrial (ET) Contact red light through the tree branches. when she saw something strange in other a green light, and the third Support Group meeting on Eric Fine photo/The Post "It was very bright and silent, the distant sky. corner had an orange pulsating Wednesday, June 2, where and was only about 100 feet up in "I peered through th e wind gl ow," she said. strangers became friends as they the air," Winchester says. "It didn't shield and thought, 'What the heck She estimates that the object Glasgow's Amy Blouse helped the Dragons to the shared experiences of the bizarre surprise either of us. I actually is that?"' was as high as three heights of a girl's state softball championship game, where they kind. -

Michigan State University College of Engineering Spring 2021 Design Day

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING SPRING 2021 DESIGN DAY Executive Partner Sponsor We at Amazon are honored to partner with the College of Engineering and Michigan State University to highlight the amazing work of MSU Students for Design Day Spring 2021. Amazon has witnessed innovation, creativity and solution-focused ideas from previous Design Days, and we know this one will be no different. MSU students work relentlessly to solve real-world problems using their skills and knowledge acquired while in the College of Engineering at MSU. These skills will help propel them into the workforce, where they will be our future engineers, leaders, innovators, entrepreneurs, and outstanding co-workers. At Amazon, we use our leadership principles every day to guide our decision making, problem solving, and discussing new ideas. We see those leadership principles integrated in the projects presented in this Design Day booklet. Students are customer obsessed as they work backwards from the customer to solve for what is really needed. They work hard to invent and simplify on behalf of customers, trying new and different experiments before finding the best simplified solution. All student teams delivered results in their projects to showcase for Design Day, and we are excited for them to be our future. Congratulations and best of luck to all the students, faculty and staff who helped make this Design Day a success for MSU and all its partners. We at Amazon Detroit are proud to be included and look forward to working with these students in corporate jobs. Amazon is always looking to hire and develop the best.