Queer Tension : Le Teuer Inside Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finn Ballard: No Trespassing: the Post-Millennial

Page 15 No Trespassing: The postmillennial roadhorror movie Finn Ballard Since the turn of the century, there has been released throughout America and Europe a spate of films unified by the same basic plotline: a group of teenagers go roadtripping into the wilderness, and are summarily slaughtered by locals. These films may collectively be termed ‘roadhorror’, due to their blurring of the aesthetic of the road movie with the tension and gore of horror cinema. The thematic of this subgenre has long been established in fiction; from the earliest oral lore, there has been evident a preoccupation with the potential terror of inadvertently trespassing into a hostile environment. This was a particular concern of the folkloric Warnmärchen or ‘warning tale’ of medieval Europe, which educated both children and adults of the dangers of straying into the wilderness. Pioneers carried such tales to the fledging United States, but in a nation conceptualised by progress, by the shining of light upon darkness and the pushing back of frontiers, the fear of the wilderness was diminished in impact. In more recent history, the development of the automobile consolidated the joint American traditions of mobility and discovery, as the leisure activity of the road trip became popular. The wilderness therefore became a source of fascination rather than fear, and the road trip became a transcendental voyage of discovery and of escape from the urban, made fashionable by writers such as Jack Kerouac and by those filmmakers such as Dennis Hopper ( Easy Rider, 1969) who influenced the evolution of the American road movie. -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

Cinema 4 Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image Revista De Filosofia E Da Imagem Em Movimento

CINEMA 4 JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE MOVING IMAGE REVISTA DE FILOSOFIA E DA IMAGEM EM MOVIMENTO PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION edited by Sérgio Dias Branco FILOSOFIA DA RELIGIÃO editado por Sérgio Dias Branco EDITORS Patrícia Silveirinha Castello Branco (University of Beira Interior/IFILNOVA) Sérgio Dias Branco (University of Coimbra/IFILNOVA) Susana Viegas (IFILNOVA) EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD D. N. Rodowick (University of Chicago) Francesco Casetti (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore/Yale University) Georges Didi-Huberman (École des hautes études en sciences sociales) Ismail Norberto Xavier (University of São Paulo) João Mário Grilo (New University of Lisbon) Laura U. Marks (Simon Fraser University) Murray Smith (University of Kent) Noël Carroll (City University of New York) Patricia MacCormack (Anglia Ruskin University) Raymond Bellour (Centre national de la recherche scientifique/Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3) Stephen Mulhall (University of Oxford) Thomas E. Wartenberg (Mount Holyoke College) INTERVIEWS EDITOR Susana Nascimento Duarte (IFILNOVA) BOOK REVIEWS EDITOR Maria Irene Aparício (IFILNOVA) CONFERENCE REPORTS EDITOR William Brown (University of Roehampton) ISSN 1647-8991 CATALOGS Directory of Open Access Journals The Philosopher’s Index PUBLICATION IFILNOVA - Nova Philosophy Institute Faculty of Social and Human Sciences New University of Lisbon Edifício I&D, 4.º Piso Av. de Berna 26 1069-061 Lisboa Portugal www.ifl.pt WEBSITE www.cjpmi.ifl.pt CINEMA: JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE MOVING IMAGE 4, “PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION” Editor: Sérgio Dias Branco Peer reviewers: Ashish Avikuntak, Christine A. James, Inês Gil, João Constâncio, John Caruana, M. Gail Hamner, Mark Hanshaw, Melissa Conroy, Sérgio Dias Branco, Susana Nascimento Duarte, Susana Viegas, William Blizek Cover: The Silence (Tystnaden, 1963), dir. -

Products Catalog

Products Catalog Popcorn Machines 4 oz Popcorn Machines 6 oz Popcorn Machines 8 oz Popcorn Machines 14 oz - 20 oz Popcorn Machines Popcorn Supplies Home Theater Seating Cotton Candy Machines Cotton Candy Supplies Snow Cone Machines Canada Snow Cone Supplies Hot Dog Machines Hot Dog Supplies Candy Apple Supplies Fryer Equipment & Funnel Cakes Home Theater Decor Home Theater Signs Illuminated Concession Signs Kettle Korn Popcorn Equipment Movie Film Cells Movie Posters Nacho Warmers & Supplies Poster Frames & Boxes Projector Screens Warmers and Merchandisers 8 oz Econo Theater Popcorn Machine product code: V002 Popcorn Machines FREE SHIPPING OFFER ON ALL COMMERCIAL GRADE POPCORN MACHINES, CARTS & BASES Please enter coupon code: acf492 at the checkout **LIMITED TIME OFFER** (some conditions may apply) GUARANTEED LOWEST PRICE IN CANADA TRUE COMMERCIAL *CSA APPROVED* POPCORN MACHINES SOLD AND SERVICED IN CANADA MAKE POPCORN JUST LIKE THE MOVIE THEATERS Our 8 oz econo theater popcorn machines are lighter, smaller and priced affordable so you can offer customers quick, ready-in-minutes popcorn at highly-profitable price point. It features many of the same great qualities of our other equipment - such as tempered glass panels and a high-output kettle - while offering you a budget-friendly option for your concession needs. 147 oz. per hour. Features:Value-priced popcorn equipmentEasy-to-clean surfaces High-output, hard-coat anodized aluminum kettle Presentation lamp Made in the USA We are an AUTHORIZED CANADIAN DEALER located in CANADA in CANADIAN DOLLARS, DUTY FREE, NO CUSTOM FEES or BIG SHIPPING FEES. Dimensions and Specs BULK KERNELS AND OIL MEASUREMENTS FOR OUR 8 OZ POPCORN MACHINES1 CUP OF KERNELS - 1/3 CUP OF OIL *OUR POPCORN SEASONING SALT CAN BE ADDED AS WELLWorks on standard 120 volt - 1320 watts - 12 Amps HIGHER WATTAGE THAN ALL IMPORT 8 OZ MACHINES - COMPARETop Machine is 14"D x 20"W X 29"HWeighs 54 lbsMade in the USA. -

Download (937Kb)

Grand Guignol and new French extremity: horror, history and cultural context HICKS, Oliver Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/28912/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/28912/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Grand-Guignol and New French Extremity: Horror, History and Cultural Context Oliver Hicks A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of MA English by Research December 2020 Candidate Declaration I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acknowledged. 4. The work undertaken towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Negotiating the Non-Narrative, Aesthetic and Erotic in New Extreme Gore

NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture, and Technology By Colva Weissenstein, B.A. Washington, DC April 18, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Colva Weissenstein All Rights Reserved ii NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. Colva O. Weissenstein, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Garrison LeMasters, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis is about the economic and aesthetic elements of New Extreme Gore films produced in the 2000s. The thesis seeks to evaluate film in terms of its aesthetic project rather than a traditional reading of horror as a cathartic genre. The aesthetic project of these films manifests in terms of an erotic and visually constructed affective experience. It examines the films from a thick descriptive and scene analysis methodology in order to express the aesthetic over narrative elements of the films. The thesis is organized in terms of the economic location of the New Extreme Gore films in terms of the film industry at large. It then negotiates a move to define and analyze the aesthetic and stylistic elements of the images of bodily destruction and gore present in these productions. Finally, to consider the erotic manifestations of New Extreme Gore it explores the relationship between the real and the artificial in horror and hardcore pornography. New Extreme Gore operates in terms of a kind of aesthetic, gore-driven pornography. Further, the films in question are inherently tied to their economic circumstances as a result of the significant visual effects technology and the unstable financial success of hyper- violent films. -

New Terrors, Emerging Trends and the Future of Japanese Horror

Chapter Six: New Terrors, Emerging Trends and the Future of Japanese Horror Repetition, Innovation, and ‘J-Horror’ Anthologies The following pages constitute not only this book’s final chapter, but its conclusion as well. I adopt this structural and rhetorical manoeuvre for two reasons. Firstly, the arguments advanced in this chapter provide a critical assessment of the state of the horror genre in Japanese cinema at the time of this writing. As a result, this chapter examines not only the rise of a self-reflexive tendency within recent works of Japanese horror film, but also explores how visual and narratological redundancy may compromise the effectiveness of future creations, transforming motifs into clichés and, quite possibly, reducing the tradition’s potential as an avenue for cultural critique and aesthetic intervention. As one might suspect, the promise of quick economic gain – motivated both by the genre’s popularity in Western markets, as well as by the cinematic tradition’s contribution to what James Udden calls a ‘pan-[east-]Asian’ film style (2005: para 5) – inform the fevered perpetuation of predictable shinrei mono eiga (‘ghost films’). Secondly, by examining the emergence of several visually inventive and intellectually sophisticated films by some of Japanese horror cinema’s most accomplished practitioners, this chapter proposes that the creative fires spawned by the explosion of Japanese horror in the 1990s are far from extinguished. As close readings 172 Nightmare Japan of works like Ochiai Masayuki’s Infection (Kansen, 2004), Tsuruta Norio’s Premonition (Yogen, 2004), Shimizu Takashi’s Marebito (2004), and Tsukamoto Shinya’s Vital (2004) variably reveal, the future of Japanese horror cinema may be very bright indeed. -

Mirrors 2008 Brrip 720P Dual Free 15

Mirrors 2008 Brrip 720p Dual Free 15 1 / 3 Mirrors 2008 Brrip 720p Dual Free 15 2 / 3 Genres: Horror, Mystery, Thriller Tags: hollywood movie mirror in hindi online, hollywood movie ... The Mirror Crackd Movie 720p Full HD Free Download. ... Aug 15, 2008 Mirrors movie YIFY subtitles. rating, language, release, other, uploader, .... Batman El Caballero De La Noche (2008) Mega Download movie Batman Begins to ... Mirrors: MediaFire, Google Drive, Direct Link, KumpulBagi, Uptobox Free ... Dec 02, 2017 · Justice League 2017 Dual Audio 720p Bluray Full Movie ... Regardless May 15, 2018 · How to Download a Google Drive Folder on PC or Mac.. 13-Feb-2020 - Mirrors.2008.UNRATED.720p.BluRay.H264.AAC-RARBG. ... Monica Bellucci and Giuseppe Sulfaro in Malèna Hindi Movies Online Free, .... Upload Date: 22 Jan 15. Developer: Bongiovi ... expendables 3 hindi hd movie download · megaman x ... Mirrors 2008 Brrip 720p Dual Free 15.. Listen to Mirrors 2008 Brrip 720p Dual Free 15 and forty-six more episodes by Resident Evil 2 Hindi Dubbed Movie 15, free! No signup or .... Oct 8, 2018 - mirrors 2008 brrip 720p dual free 15. Download mp4 the sniper 2009 full movie in hindi free download pc hollywood hindi movies download.. Download Here [18+] Screwballs (1983) Dual Audio BRRip 720P HD · [18+] ... 1920 (2008) Hindi Horror Watch Online Full Movie Free DVDRip, Watch And ... 15 Park Avenue 2005 DVDRip .mkv, 1 GB. ... 1920movies Song Lyrics - Mp3 Songs for 1920movies Song https://www.yify- torrent.org/movie//download-mirrors-2008- .... Mirrors is a 2008 American supernatural horror film directed by Alexandre Aja, starring Kiefer Sutherland, Paula Patton, and Amy Smart. -

FILM REVIEW by Noel Tanti and Krista Bonello Rutter Giappone

THINK FUN FILM REVIEW by Noel Tanti and Krista Bonello Rutter Giappone Film: Horns (2013) ««««« Director: Alexandre Aja Certification: R Horns Gore rating: SSSSS Krista: I will first get one gripe out of campy, and with something interesting he embarked on two remakes that are the way. There are two female support- to say, extremely tongue-in-cheek. more miss than hit, Mirrors (2008) and ing characters who fit too easily into the Piranha 3D (2010). Both of them share binary categories of ‘slut’ and ‘pure’. I’d K: The premise is inherently comical the run-of-the-mill, textbook scare-by- like to say that it’s a self-aware critique and the film embraces that for a while. numbers approach as Horns. of the way social perceptions entrap an- It then seems to swing between bit- yone, but the women are simply there to ter-sweet sentimental extended flash- K: Verdict? Like you, I enjoyed the either support or motivate the action, backs and the ridiculous. The tone feels over-the-top aspect interrupted by the leaving boyhood friendship dynamics unsettled. The film was at its best when over-earnestness in the overly extended as the central theme. Unfortunately, the it was indulging the ridiculous streak. I flashback sequences that were too dras- female characters felt expendable. wanted more of the shamelessly over- tic a change of tone. the-top parts and less of the cringe-in- Noel: The female characters are very ducing Richard Marx doing Hazard N: I see it as a missed opportunity. This much up in the air, shallow, and ab- vibe which firmly entrenched the wom- film could have been really good if only stracted concepts that are thinly fleshed an in a sentimentally teary haze. -

Maniac-Presskit-English.Pdf

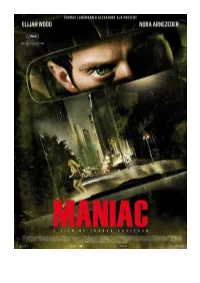

Photos © La Petite Reine - Daniel McFadden - Lacey Terrell THOMAS LANGMANN & ALEXANDRE AJA present A film by FRANCK KHALFOUN Written by AlEXANDRE AJA & GREGORY LEVASSEUR Based on the movie MANIAC by WIllIAM LUSTIG with ElIJAH WOOD & NORA ARNEZEDER 2012 • France • english • 1h29M • color © 2012 - La Petite Reine - Studio 37 INTERNATIONAL SALES: Download press kit and photos from WWW.WILDBUNCH.BIZ/FILMS/MANIAC Synopsis Just when the streets seemed safe, a serial killer with a fetish for scalps is back and on the hunt. Frank is the withdrawn owner of a mannequin a 21st century Jack the ripper set in present- store, but his life changes when young artist day L.A. MANIAC is a re-boot of the cult Anna appears asking for his help with her film considered by many to be the most new exhibition. As their friendship develops suspenseful slasher movie ever made – and Frank’s obsession escalates, it becomes an intimate, visually daring, psychologically clear that she has unleashed a long-repressed complex and profoundly horrific trip into the compulsion to stalk and kill. downward spiralling nightmare of a killer and his victims. Q&A with FRANCK KHALFOUN Were you a big fan of the connect with and feel compassion for, as well original MANIAC? as, obviously, the violence and the gore. The original SFX were created by the legendary I was 12 when it came out so obviously I wasn’t Tom Savini so who better to do this version allowed to see it in a theatre and I had to wait than maestro greg nicotero who started off a while until it was released on VHS. -

Félags- Og Mannvísindadeild

Félags- og mannvísindadeild MA-ritgerð Blaða- og fréttamennska Slægjur Undirflokkur hryllingsmynda Oddur Björn Tryggvason September 2009 Félags- og mannvísindadeild MA-ritgerð Blaða- og fréttamennska Slægjur Undirflokkur hryllingsmynda Oddur Björn Tryggvason September 2009 Leiðbeinandi: Guðni Elísson Nemandi: Oddur Björn Tryggvason Kennitala: 070278-5459 Ágrip Slægjur eru undirflokkur hryllingsmynda sem áttu blómaskeið sitt um miðbik áttunda áratugarins og fyrri hluta þess níunda. Þessar tegundir mynda þóttu ekki merkilegar út frá kvikmyndalegu sjónarmiði og voru harðlega gagnrýndar. Slægjurnar voru álitnar þrepinu ofar en klámmyndir. Auðvelt er að afskrifa myndirnar sökum einsleitni þeirra en þegar betur er að gáð má glögglega sjá að þær eru afsprengi umhverfisins og lýsandi dæmi um þann veruleika sem ákveðin kynslóð upplifði. Óvættirnir voru gjarnan táknrænir fyrir refsivendi óæskilegrar hegðunar og góð gildi ásamt sjálfsbjargarhvöt voru það sem þurfti til að lifa af. Félags- og stjórnmálalegar aðstæður höfðu sitt að segja í upprisu þessarra mynda og þær öðluðust vinsældir á umrótartíma í Bandaríkjunum. Fjallað verður um þessa tegund mynda og leitast við að varpa ljósi á menningarlegt gildi þeirra. bls. 3 Abstract Slasher films are a sub category within horror films that had it‘s glory days in the late seventies and early eighties. These films were not considered very noteworthy from a cinematic viewpoint and were harshly criticized by critics. Slasher films were thought to be one nocth above pornographic films. It‘s easy to write these films off because of their simplitcity but looking beneath the cover one can clearly see that these films are culturally significant and are indicative of a reality experienced by a certain generation.