Download (937Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity Christopher Butler University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity Christopher Butler University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Butler, Christopher, "Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4648 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity by Christopher Jason Butler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Film Studies Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Amy Rust, Ph. D. Scott Ferguson, Ph. D. Silvio Gaggi, Ph. D. Date of Approval: July 2, 2013 Keywords: Film, Violence, France, Transgression, Memory Copyright © 2013, Christopher Jason Butler Table of Contents List of Figures ii Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Recognizing Influence -

Negotiating the Non-Narrative, Aesthetic and Erotic in New Extreme Gore

NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture, and Technology By Colva Weissenstein, B.A. Washington, DC April 18, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Colva Weissenstein All Rights Reserved ii NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. Colva O. Weissenstein, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Garrison LeMasters, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis is about the economic and aesthetic elements of New Extreme Gore films produced in the 2000s. The thesis seeks to evaluate film in terms of its aesthetic project rather than a traditional reading of horror as a cathartic genre. The aesthetic project of these films manifests in terms of an erotic and visually constructed affective experience. It examines the films from a thick descriptive and scene analysis methodology in order to express the aesthetic over narrative elements of the films. The thesis is organized in terms of the economic location of the New Extreme Gore films in terms of the film industry at large. It then negotiates a move to define and analyze the aesthetic and stylistic elements of the images of bodily destruction and gore present in these productions. Finally, to consider the erotic manifestations of New Extreme Gore it explores the relationship between the real and the artificial in horror and hardcore pornography. New Extreme Gore operates in terms of a kind of aesthetic, gore-driven pornography. Further, the films in question are inherently tied to their economic circumstances as a result of the significant visual effects technology and the unstable financial success of hyper- violent films. -

Phantom Limb : a Gripping Psychological Thriller Pdf Free Download

PHANTOM LIMB : A GRIPPING PSYCHOLOGICAL THRILLER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lucinda Berry | 260 pages | 15 Dec 2016 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781541034952 | English | none Phantom Limb : A Gripping Psychological Thriller PDF Book If she's not chasing her eight-year-old son around, you can find her running the streets of Los Angeles prepping for her next marathon. Cady Maddix survived a brutal upbringing—emotionally scarred but hardened—with a will for self-preservation. Run-down sections of the city have been gentrified, with the higher real estate values and tony shops that accompany such startling changes. A great war, a great love, and the mythology that unites them; The Hawkman: A Fairy Tale of the Great War is a lyrical adaptation of a beloved classic. Jeffery Deaver J. Rate this:. See details. Please sign up to continue. As she delves deeper into the mystery surrounding Emily's death, she discovers shocking secrets and holes in her memory that force her to remember what she's worked so hard to forget-the beatings, the blood, the special friends. Newly married, newly pregnant, Lucy Robin is having trouble remembering the little things. Gor is keeping busy. But this is just the first act in this chilling, edge-of-your- seat thriller. Kelly recently posted… Phantom Limb by Lucinda Berry. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. In a post-apocalyptic Africa, the world has changed in many ways; yet in one region genocide between tribes still bloodies the land. Enemy nations The author of the acclaimed mystery The Unquiet Dead delivers her first fantasy novel—the opening installment in a thrilling quartet—a tale of religion, oppression, and political intrigue that radiates with heroism, wonder, and hope. -

Cinema / Art / Café

0116 242 2800 BOX OFFICE PHOENIX.ORG.UK BOOK ONLINE WHAT’S ON BOX OFFICE PHOENIX.ORG.UK MAY 2018 0116 242 2800 BAR É Available as Midweek Matinees – see p15 CINEMA / ART / CAF CINEMA / ART BOX OFFICE 0116 242 2800 FILMS SHORT PHOENIX.ORG.UK P. 12 COURSES Made possible with the support of P. 10 STAGE ON SCREEN EDIE Fri 25 May – Thu 7 Jun P. 8 Phoenix is a registered charity, No 701078 It’s been a long haul this winter, Our Film School course – an 8-week ART & with early April seeming more practical guide to filmmaking – starts on DIGITAL like late November (was more 10 May, and we also dip into the life and fog really necessary?) but finally work of Pedro Almodovar (p10). Book CULTURE online or at Box Office. FAMILY P. 6 it might be possible for us to cast FUN off our thermals and dig out our Film-wise, highlights include the T-shirts. Hurrah. ludicrously watchable Love Simon P. 4 (p13), which is garnering rave reviews With a third of the year behind us, May worldwide; Ian McEwan adaptation COMING NEXT MONTH brings with it many delights – warbling On Chesil Beach (p16) starring Saoirse warblers, bumbling bees, half-term hols… Ronan; gripping psychological thriller and the Spark Festival, when we open our Beast (p14), which is causing a storm on digital playground filled with free creative the international festival circuit; and the technology treats for families (p4). sublime My Golden Days (p16) – a true SOLO: A STAR WARS STORY We’re exploring artificial intelligence at the Gallic gem. -

NVS 2-2-14 Announcements

Announcements: CFPs, conference notices, & current & forthcoming projects and publications of interest to neo-Victorian scholars (compiled by Marie-Luise Kohlke & Sneha Kar Chaudhuri ) ***** NOTE: Beginning with the fourth issue of Neo-Victorian Studies (to be published summer 2010), we are inviting brief 1-2 paragraph reports from organisers or participants of recent international symposia, conferences and/or conference sessions, which specifically addressed neo-Victorian issues. NVS is especially keen to publish reports on events outside Europe and North America, to facilitate a more comprehensive overview of neo- Victorian scholarship worldwide. CFPs: Journals, Special Issues & Collections Neo-Victorian Gothic: Horror, Violence, and Degeneration in the Re-Imagined Nineteenth Century (Edited Collection) Contributions are invited for the third volume in the forthcoming Neo- Victorian Studies series by Rodopi. This collection will explore the subversive potential, but also the ideologically conservative implications, of recycling the Gothic genre in contemporary historical fiction, film, and further aesthetic media that re-imagine the nineteenth century in Britain, its colonial territories, and other geographical settings. In her recent study of Gothic postmodernism, Maria Beville argues that it is terror which constitutes “the potent link between the gothic and the postmodern” (Gothic-postmodernism , 2009). Perhaps, then, neo-Victorianism might be said to revive the spirit of terror in order to link our postmodern “culture of death”, our obsession with terror and even with terrorism (Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death , 1993), back to the angst-ridden uncertainties occasioned by Victorian socio-political and cultural metamorphoses. What is the purpose of the contemporary revival of the nineteenth-century fascination with the irrational, the mysterious and the monstrous, and what questions does it raise for subjectivity and/or ontology? To what extent is Neo-Victorian Studies 2:2 (Winter 2009/2010) pp. -

2014-2015 General Catalog

UNIVERSITY OF THE PACIFIC General Catalog 2014-2015 Table of Contents University of the Pacific ............................................................................ 3 Visual Arts ..................................................................................... 181 General Catalog 2014-2015 ..................................................................... 4 Cross-Disciplinary Majors and Programs ....................................... 188 General Information .................................................................................. 6 Conservatory of Music ......................................................................... 192 Pacific Learning Objectives ............................................................... 6 Music Composition ........................................................................ 197 Academic Units .................................................................................. 7 Music Performance ........................................................................ 199 General Education ............................................................................. 7 Music Education ............................................................................ 204 Admission Requirements ................................................................... 8 Music History ................................................................................. 207 Tuition and Fees .............................................................................. 13 Music Management ...................................................................... -

FILM REVIEW by Noel Tanti and Krista Bonello Rutter Giappone

THINK FUN FILM REVIEW by Noel Tanti and Krista Bonello Rutter Giappone Film: Horns (2013) ««««« Director: Alexandre Aja Certification: R Horns Gore rating: SSSSS Krista: I will first get one gripe out of campy, and with something interesting he embarked on two remakes that are the way. There are two female support- to say, extremely tongue-in-cheek. more miss than hit, Mirrors (2008) and ing characters who fit too easily into the Piranha 3D (2010). Both of them share binary categories of ‘slut’ and ‘pure’. I’d K: The premise is inherently comical the run-of-the-mill, textbook scare-by- like to say that it’s a self-aware critique and the film embraces that for a while. numbers approach as Horns. of the way social perceptions entrap an- It then seems to swing between bit- yone, but the women are simply there to ter-sweet sentimental extended flash- K: Verdict? Like you, I enjoyed the either support or motivate the action, backs and the ridiculous. The tone feels over-the-top aspect interrupted by the leaving boyhood friendship dynamics unsettled. The film was at its best when over-earnestness in the overly extended as the central theme. Unfortunately, the it was indulging the ridiculous streak. I flashback sequences that were too dras- female characters felt expendable. wanted more of the shamelessly over- tic a change of tone. the-top parts and less of the cringe-in- Noel: The female characters are very ducing Richard Marx doing Hazard N: I see it as a missed opportunity. This much up in the air, shallow, and ab- vibe which firmly entrenched the wom- film could have been really good if only stracted concepts that are thinly fleshed an in a sentimentally teary haze. -

Maniac-Presskit-English.Pdf

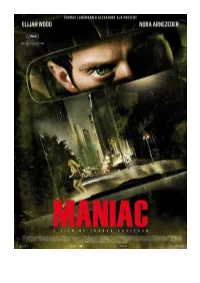

Photos © La Petite Reine - Daniel McFadden - Lacey Terrell THOMAS LANGMANN & ALEXANDRE AJA present A film by FRANCK KHALFOUN Written by AlEXANDRE AJA & GREGORY LEVASSEUR Based on the movie MANIAC by WIllIAM LUSTIG with ElIJAH WOOD & NORA ARNEZEDER 2012 • France • english • 1h29M • color © 2012 - La Petite Reine - Studio 37 INTERNATIONAL SALES: Download press kit and photos from WWW.WILDBUNCH.BIZ/FILMS/MANIAC Synopsis Just when the streets seemed safe, a serial killer with a fetish for scalps is back and on the hunt. Frank is the withdrawn owner of a mannequin a 21st century Jack the ripper set in present- store, but his life changes when young artist day L.A. MANIAC is a re-boot of the cult Anna appears asking for his help with her film considered by many to be the most new exhibition. As their friendship develops suspenseful slasher movie ever made – and Frank’s obsession escalates, it becomes an intimate, visually daring, psychologically clear that she has unleashed a long-repressed complex and profoundly horrific trip into the compulsion to stalk and kill. downward spiralling nightmare of a killer and his victims. Q&A with FRANCK KHALFOUN Were you a big fan of the connect with and feel compassion for, as well original MANIAC? as, obviously, the violence and the gore. The original SFX were created by the legendary I was 12 when it came out so obviously I wasn’t Tom Savini so who better to do this version allowed to see it in a theatre and I had to wait than maestro greg nicotero who started off a while until it was released on VHS. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

MARGINALIZATION in the WORKS of MARÍA LUISA BEMBERG, LUCRECIA MARTEL, and LUCÍA PUENZO By

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2017 The aN rrative Of The Outsider: Marginalization In The orW ks Of María Luisa Bemberg, Lucrecia Martel, And Lucía Puenzo Natalie Nagl Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Nagl, Natalie, "The aN rrative Of The Outsider: Marginalization In The orkW s Of María Luisa Bemberg, Lucrecia Martel, And Lucía Puenzo" (2017). Wayne State University Dissertations. 1851. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/1851 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE NARRATIVE OF THE OUTSIDER: MARGINALIZATION IN THE WORKS OF MARÍA LUISA BEMBERG, LUCRECIA MARTEL, AND LUCÍA PUENZO by NATALIE NAGL DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2017 MAJOR: SPANISH Approved By: __________________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY NATALIE NAGL 2017 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge