UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Desert History

History Of Palm Desert John Fraim John Fraim 189 Keswick Drive New Albany, OH 43054 760-844-2595 [email protected] www.symbolism.org © 2013 – John Fraim Special Thanks To Palm Desert Historical Society & Hal Rover Brett Romer Duchess Emerson Lincoln Powers Carla Breer Howard 2 “The desert has gone a-begging for a word of praise these many years. It never had a sacred poet; it has in me only a lover … This is a land of illusions and thin air. The vision is so cleared at times that the truth itself is deceptive.” John Charles Van Dyke The Desert (1901) “The other Desert - the real Desert - is not for the eyes of the superficial observer, or the fearful soul or the cynic. It is a land, the character of which is hidden except to those who come with friendliness and understanding. To these the Desert offers rare gifts … health-giving sunshine—a sky that is studded with diamonds—a breeze that bears no poison—a landscape of pastel colors such as no artist can duplicate—thorn-covered plants which during countless ages have clung tenaciously to life through heat and drought and wind and the depredations of thirsty animals, and yet each season send forth blossoms of exquisite coloring as a symbol of courage that has triumphed over terrifying obstacles. To those who come to the Desert with friendliness, it gives friendship; to those who come with courage, it gives new strength of character. Those seeking relaxation find release from the world of man-made troubles. For those seeking beauty, the Desert offers nature’s rarest artistry. -

Pioneertown Mane Street Historic District

NPS Form 10-900 OMB Control No. 1024-0018 expiration date 03/31/2022 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: _Pioneertown Mane Street Historic District DRAFT Other names/site number: N/A Name of related multiple property listing: N/A ___________________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _Mane Street____________________________________________ City or town: _Pioneertown_ State: __California _County: _San Bernardino___________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties -

Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Advertisements, Back Issues, About Cutbank, Back Cover

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 21 CutBank 21 Article 37 Fall 1983 Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Advertisements, Back Issues, About CutBank, Back Cover Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation (1983) "Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Advertisements, Back Issues, About CutBank, Back Cover," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 21 , Article 37. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss21/37 This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTRIBUTORS BRUCE BEASLEY is a native of Macon, Georgia; graduated from Oberlin College in the M.F.A. writing program at Columbia University; works as an editor at Georgia State University and his work has appeared in Quarterly West, Southern Poetry Review andColumbia: A Magazine of Poetry and Prose. JOHANNES BOBROWSKI was born in 1917 in Tilsit, East Prussia. Between 1960 and 1965, he published two books of poetry, two novels, and two collections of short stories. He died in East Berlin in 1965. SCOTT DAVIDSON grew up in Great Falls and received his M.F.A. in creative writing from the University of Montana. He lives in Missoula with his wife, Sharon, works for Montana’s Poets in the Schools program, and has received many favorable comments accompanying his rejection slips. -

DESCEND INTO the DEEP Adventure Into the Newly Opened Limestone Caves Mitchell Caverns

THIS AIRBNB DOUBLES AS A NEW TAKES FOR OUTPOST PROJECTS CONTEMPORARY ART GALLERY TAROT TRENDS MODERN READINGS March 2018 DESCEND INTO THE DEEP Adventure into the newly opened limestone caves Mitchell Caverns. MARCH 2018 $3.95 US desertsun.com/desertmagazine 0018_000_Cover_V3.indd 1 2/19/18 3:23 PM 0018_000_Cover_V3.indd 2 2/19/18 5:05 PM 0018_001-005_Contents_V3.indd 1 2/19/18 2:22 PM 2 | DESERT • March 2018 0018_001-005_Contents_V3.indd 2 2/19/18 2:22 PM 0018_001-005_Contents_V3.indd 3 2/19/18 2:22 PM CONTENTS MARCH 2018 6 A Letter from the Editor 8 Calendar March events 10 In the News Dispatches from the desert 12 Fashion Grab a graphic tee from local shops 14 Natural Beauty Sandee Ferman and Callie Milford, the mother-daughter duo behind vegan skin care line No Tox Life, give us the lowdown on an all-natural lifestyle 18 Sip Didn’t think Joshua Tree recording studio Rancho de la Luna could get any cooler? Meet its new mezcal 20 Wellness 30 JOURNEY TO THE CENTER Modern tarot readers turn to a centuries-old cartomancy technique to Words by Rick Marino facilitate personal growth and healing Photographs by Lance Gerber 24 Art Veteran band tour manager Rick Marino drives us to Essex to In Joshua Tree, artist Angel Chen is descend into the now-open Mitchell Caverns. cultivating a life and practice connected to nature 28 Looking Back The legend – and truth – of original desert rat, Harry Oliver 56 Final Thoughts One artist’s take on how we seek – and find – beauty in the desert VOLUME 17 ISSUE 3 EDITOR PRESIDENT/PUBLISHER KRISTIN SCHARKEY MARK J. -

University of Arizona Poetry Center Records Collection Number: UAPC.01

University of Arizona Poetry Center Records Collection Number: UAPC.01 Descriptive Summary Creator: University of Arizona Poetry Center Collection Name: University of Arizona Poetry Center Records Dates: 1960- Physical Description: 105 linear feet Abstract: This collection contains correspondence, administrative records, board meeting minutes, printed materials, audiovisual recordings, and scrapbooks related to the unique history of the Poetry Center and its prominent role in Southern Arizona’s literary arts landscape. “Author files” contain records and correspondence pertaining to poets such as Robert Frost, Kenneth Koch, and Allen Ginsberg. Collection Number: UAPC.01 Repository: University of Arizona Poetry Center 1508 E. Helen St. Tucson, AZ 85721 Phone: 520-626-3765 Fax: 520-621-5566 URL: http://poetry.arizona.edu Historical Note The University of Arizona Poetry Center began in 1960 as a small house and a collection of some 500 volumes of poetry, donated to the University of Arizona by poet and novelist Ruth Stephan. It has grown to house one of the most extensive collections of contemporary poetry in the United States. Since 1962, the Poetry Center has sponsored one of the nation’s earliest, longest-running, and most prestigious reading series, the Visiting Poets and Writers Reading Series, which continues to the present day. The Poetry Center also has a long history of community programming including classes and workshops, lectures, contests, youth programming, writers in residence, and poetry workshops in Arizona penitentiaries. Its leadership has included noted authors such as Richard Shelton, Alison Hawthorne Deming, and LaVerne Harrell Clark. University of Arizona Poetry Center Records UAPC.01 Page 1 of 72 Scope and Content Note This collection contains correspondence, administrative records, board meeting minutes, printed materials, audiovisual recordings, and scrapbooks related to the unique history of the Poetry Center and its prominent role in Southern Arizona’s literary arts landscape. -

Poetry Editor Ofcalifornia Quarterly for Two Years

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 16 CutBank 16 Article 42 Spring 1981 Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Back Issues, Advertisements, Back Cover Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation (1981) "Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Back Issues, Advertisements, Back Cover," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 16 , Article 42. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss16/42 This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTRIBUTORS ANSEL ADAMS has exhibited his photographs throughout the world, and has written extensively about photography. Recipient of three Guggenheim Fellowships and Yale’s Chubb Fellowship, his latest book of photographs is entitled Yosemite and the Range of Light (1979). JAMES BOND'S fiction has appeared in theIntro series and inWillow Springs M agazine. He lives in Cusick, Washington. HARRISON BRANCH studied photography at Yale with Walker Evans and Paul Caponigro. He is currently teaching photography at Oregon State University, and photographing the Northwest. EDNA BULLOCK began making photographs eight years ago. She lives and works in Monterey, California. WYNN BULLOCK'S photographs can be seen in the major collections in the world. The most recent monographs on his workWynn are Bullock, (1976) andThe Photograph as Symbol, (1976). WILLIAM CHAMBERLAIN has planted over 200,000 Douglas Fir trees, in the past three years, near Astoria, Oregon, where he lives. -

City Landmark Assessment & Evaluation

CITY LANDMARK ASSESSMENT & EVALUATION REPORT WITCH’S HOUSE JANUARY 2013 516 North Walden Drive, Beverly Hills, CA Prepared for: City of Beverly Hills Community Development Department Planning Division 455 Rexford Drive, Beverly Hills, CA 90210 Prepared by: Jan Ostashay Principal Ostashay & Associates Consulting PO BOX 542, Long Beach, CA 90801 CITY LANDMARK ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION Witch’s House 516 North Walden Drive Beverly Hills, CA 90210 APN: 4345‐030‐010 INTRODUCTION This landmark assessment and evaluation report, completed by Ostashay & Associates Consulting for the City of Beverly Hills, documents and evaluates the local significance and landmark eligibility of the Witch’s House located at 516 Walden Drive in the City of Beverly Hills, California. This assessment report includes a discussion of the survey methodology used, a summarized description of the property, a brief history of the property, the landmark criteria considered, evaluation of significance, photographs, and applicable supporting materials. METHODOLOGY The landmark assessment was conducted by Jan Ostashay, Principal with Ostashay & Associates Consulting. In order to identify and evaluate the subject property as a potential local landmark, an intensive‐level survey was conducted. The assessment included a review of the National Register of Historic Places (National Register) and its annual updates, the California Register of Historical Resources (California Register), and the California Historic Resources Inventory list maintained by the State Office of Historic Preservation (OHP) in order to determine if any previous evaluations or survey assessments of the property had been performed. The results of the records search indicated that the subject property had been previously surveyed and documented, and was found through those surveys to be eligible for listing in the National Register under criteria associated with historical events, important personages, and architecture. -

Memorial Statements of the Cornell University Faculty 1960-1969 Volume 4

Memorial Statements of the Cornell University Faculty 1960-1969 Volume 4 Memorial Statements of the Cornell University Faculty The memorial statements contained herein were prepared by the Office of the Dean of the University Faculty of Cornell University to honor its faculty for their service to the university. P.C.Tobias de Boer, proofreader J. Robert Cooke, producer ©2010 Cornell University, Office of the Dean of the University Faculty All Rights Reserved Published by the Internet-First University Press http://ifup.cit.cornell.edu/ Founded by J. Robert Cooke and Kenneth M. King The contents of this volume are openly accessible online at ecommons.library.cornell.edu/handle/1813/17811 Preface The custom of honoring each deceased faculty member through a memorial statement was established in 1868, just after the founding of Cornell University. Annually since 1938, the Office of the Dean of the Faculty has produced a memorial booklet which is sent to the families of the deceased and also filed in the university archives. We are now making the entire collection of memorial statements (1868 through 2009) readily available online and, for convenience, are grouping these by the decade in which the death occurred, assembling the memorials alphabetically within the decade. The Statements for the early years (1868 through 1938, assembled by Dean Cornelius Betten and now enlarged to include the remaining years of the 1930s, are in volume one. Many of these entries also included retirement statements; when available, these follow the companion memorial statement in this book. A CD version has also been created. A few printed archival copies are being bound and stored in the Office of the Dean of the Faculty and in the Rare and Manuscript Collection in Kroch Library. -

Mythical River: Encounters with Water in the American Southwest Melissa Lynn Sevigny Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 Mythical River: Encounters with Water in the American Southwest Melissa Lynn Sevigny Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Climate Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Sevigny, Melissa Lynn, "Mythical River: Encounters with Water in the American Southwest" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13172. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13172 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythical river Encounters with water in the American Southwest by Melissa L. Sevigny A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Creative Writing and Environment Program of Study Committee: Debra Marquart, Major Professor Rick Bass Michael Dahlstrom Stephen Pett Richard Schultz Matthew Wynn Sivils Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2013 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. iii PROLOGUE. THE GOOD-LUCK RIVER .......................................................... -

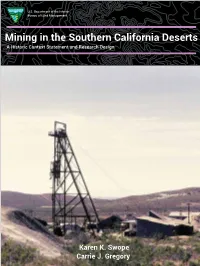

Mining in the Southern California Deserts a Historic Context Statement and Research Design Bob Wick, BLM

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Mining in the Southern California Deserts A Historic Context Statement and Research Design Bob Wick, BLM Karen K. Swope Carrie J. Gregory Mining in the Southern California Deserts: A Historic Context Statement and Research Design Karen K. Swope and Carrie J. Gregory Submitted to Sterling White Desert District Abandoned Mine Lands and Hazardous Materials Program Lead U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 Prepared for James Barnes Associate State Archaeologist U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California State Office 2800 Cottage Way, Ste. W-1928 Sacramento, CA 95825 and Tiffany Arend Desert District Archaeologist U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 Technical Report 17-42 Statistical Research, Inc. Redlands, California Mining in the Southern California Deserts: A Historic Context Statement and Research Design Karen K. Swope and Carrie J. Gregory Submitted to Sterling White Desert District Abandoned Mine Lands and Hazardous Materials Program Lead U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 Prepared for James Barnes Associate State Archaeologist U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California State Office 2800 Cottage Way, Ste. W-1928 Sacramento, CA 95825 and Tiffany Arend Desert District Archaeologist U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management California Desert District Office 22835 Calle San Juan de los Lagos Moreno Valley, CA 92553 Technical Report 17-42 Statistical Research, Inc. -

Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Back Issues, Advertisements, Back Cover

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 12 CutBank 12 Article 51 Spring 1979 Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Back Issues, Advertisements, Back Cover Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation (1979) "Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Back Issues, Advertisements, Back Cover," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 12 , Article 51. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss12/51 This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTRIBUTORS JOHN ADDIEGO is a VISTA worker and assistant poetry editorNorthwest of Review. He lives in Berkeley, California. TIM BARNES lives in Oregon City, Oregon and works for the Poets in the Schools program. LEE BASSETT’s collection of poemsThe Mapmaker’s Lost Daughter is due out from Confluence Press this summer. He resides in Missoula, Montana. KEVIN CLARK is poetry editor forCalifornia Quarterly, teaches writing at the University of California/Davis, and has poems current or forthcomingThe in Florida Quarterly, The Georgia Review and other places. STEVEN CRAMER has poems out or forthcomingPoetry, in The Antioch Review, Ploughshares, The Nation, Ohio ReviewandCrazyhorse. He works for David R. Godine Publishers in Boston. PAUL CORRIGAN has had work Poetryin Northwest and lives in Glens Falls, New York, where he teaches in the New York State Poets in the Schools program. -

THE UNIVERSITY of ARIZONA POETRY CENTER: Celebrating 50 Years

THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA POETRY CENTER: Celebrating 50 Years TABLE OF CONTENTS 1–15 A Memoir of the Poetry Center Looking Back from1984 by LaVerne Harrell Clark 17–37 Lois Shelton and the Round Tuit by Richard Shelton 39–61 People, Habitat, Poetry by Alison Hawthorne Deming THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA POETRY CENTER: Celebrating 50 Years Edited by Gail Browne and Rodney Phillips 63–85 Designed by Ellen McMahon and Kelly Leslie To Gather and Appeal: A Community Orientation to Poetry Copyright © 2010 Arizona Board of Regents, Estate of LaVerne Harrell Clark, Richard by Gail Browne and Frances Sjoberg Shelton, Alison Hawthorne Deming, Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute, Gail Browne, and Frances Sjoberg. The Poetry Center gratefully thanks the Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute and the Poetry Foundation for permission to print Alison Hawthorne Deming’s essay, which was commissioned by the HMPI for inclusion in a forthcoming anthology of essays about bringing poetry into communities. The University of Arizona Poetry Center thanks the Southwestern Foundation for a grant in support of this publication. This publication has also benefited from the support of the University of Arizona Executive Vice President and Provost Meredith Hay and College of Humanities Dean Mary E. Wildner-Bassett. Wendy Burk and Cybele Knowles provided excellent research and editorial assistance. All errors and omissions are the editors’ alone. Over the past fifty years, the following individuals have served as directors and acting directors of the Poetry Center: A. Laurence Muir, LaVerne Harrell Clark, Richard Shelton, Mary Louise Robins, John Weston, Robert Longoni, Lois Shelton, Alison Hawthorne Deming, Mark Wunderlich, Jim Paul, Frances Sjoberg, and Gail Browne.